- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

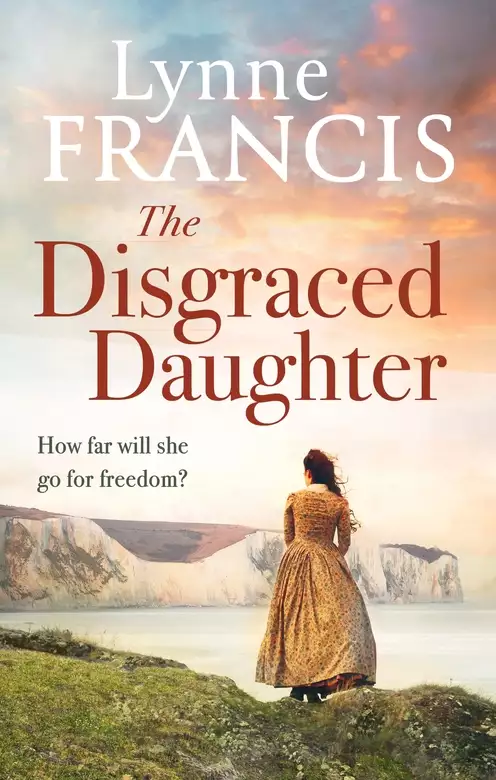

A gripping and heart-warming new saga of love, betrayal and secrets from Lynne Francis, author of A Maid's Ruin, perfect for fans of Dilly Court and Rosie Goodwin

How far will she go for freedom?

Kent, 1828. Lizzie Carey of Castle Bay is trapped in a life she never chose - endless days of cooking, cleaning, and caring for her five younger siblings after her elder sister Nell's marriage. She longs to escape, but it seems like an impossible dream.

That is, until she meets the enigmatic Mrs. Simmonds, who promises Lizzie a future far beyond the confines of her small town. The allure of a new life in Canterbury draws Lizzie into a world she never imagined, but it soon becomes clear that nothing is as it seems . . .

Torn between family loyalty and the tantalising unknown, Lizzie is forced to confront a truth darker than she could have imagined.

Praise for Lynne Francis

'Impressively researched . . . I loved this five-star book' Kay Brellend

'An engaging, thoroughly researched tale of youthful naivety and courage in the face of adversity, full of rich detail and imagination. Highly recommended!' RoNA award-winning, bestselling novelist Tania Crosse

'A compelling and captivating historical saga rich in atmosphere, emotion and heart' Goodreads Reviewer

Release date: April 8, 2025

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 90000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Disgraced Daughter

Lynne Francis

‘Look at us,’ she would declare, sweeping the front step with vigour. ‘Eight of us living here, and from the outside you’d think it was the grandest house hereabouts, rather than the smallest cottage in the road.’

Lizzie closed the gate behind her and set off at a brisk pace, the March wind bringing an instant flush to her cheeks. Despite the sunshine, the air was still chilly. She was glad to be outside, even though her errand wouldn’t keep her away from home for long. Since her eldest sister, Nell, had left to be married, Lizzie, aged sixteen, had taken up all of her duties. With five children under the age of twelve at the fireside, every day was a non-stop routine of cooking, washing, cleaning, nose-wiping and quarrel management. It felt to Lizzie that the only time she had to herself was when she fell into bed at night – a bed shared with sleeping younger family members – or when she could escape into Castle Bay to fetch provisions from old Widow Booth’s shop in Middle Street.

She was on her way there now, and she was so delighted by the fresh air that she didn’t notice the glances she attracted from a woman walking towards her along Middle Street. Even had she done so, she wouldn’t have been aware that the woman stopped the instant she passed her, turned and watched Lizzie’s journey up the street, before following her at a slower pace.

Lizzie made a striking sight, her auburn hair glinting in the sunlight, her pale skin enhancing the rosiness the wind had brought to her cheeks. She had no time to spend before the looking-glass, though, and was unaware that her petite, trim figure had blossomed into womanhood, attracting admiring glances. What she was aware of, however, was a sense of dissatisfaction. It had been accepted without question in the family that Lizzie would step into Nell’s shoes and become her mother’s helpmeet. Lizzie hadn’t considered anything different at the time. But now, in the long hours spent taking care of the household, she found herself wondering whether this was all there was to life: hard work in her mother’s house, then, if she followed the path expected of her, marriage to someone in the town and a similar life in another small cottage close by. Nell, of course, had done rather better than that and was now living in Hawksdown in a brewery cottage much the same size as the Careys’ house, but occupied just by Nell and her husband Thomas.

What alternative was there? Lizzie had discovered it was better not to dwell on it, for there seemed to be no answer. So, today, she was determined to enjoy the brief moments of freedom she had been granted.

‘You look to be enjoying the lovely weather.’

Focused on adjusting the purchases from Widow Booth’s shop in her basket, Lizzie glanced up at being addressed.

‘I couldn’t help noticing you just now.’ It was her follower who spoke: a woman in her late forties wearing a costume somewhat smarter than one might expect to see in Middle Street. She had blonde hair swept back under a stylish hat, and she was regarding Lizzie with a friendly expression on her handsome face.

‘Yes, the sunshine is very welcome after the weather we’ve had all week.’ Lizzie hoped she was managing to be both polite and discouraging. Why would a stranger wish to strike up conversation with her?

‘Would you mind if I walk along with you a little way?’ the woman continued. ‘I have a question I hesitate to ask, but I will never forgive myself if I don’t.’

‘Oh?’ Lizzie was instantly intrigued.

‘Yes, I wondered whether you had ever considered a life away from here.’ The woman gestured at the street they were walking along. It held a mixture of taverns and houses, most of them for the sole purpose of entertaining the sailors at anchor in Castle Bay, whether with ale or women.

‘I’m assuming you’ve lived here all your life. It’s rather a mean little place, I must say. I come every now and then to visit family and I always hope for some improvement, to no avail,’ she continued. ‘But you must excuse me – I haven’t introduced myself. I’m Mrs Simmonds and I’m the owner of an establishment in Canterbury. I’m looking for a young woman such as yourself who might come and work with me there.’

Lizzie experienced a range of emotions. She was curious to know more, but feared what she would hear. And even though she had been feeling trapped by her life, she bridled to hear Mrs Simmonds refer to Castle Bay in disparaging tones.

‘Well,’ she replied, with some spirit, ‘if you are referring to the kind of establishments that we are walking past,’ and she gestured to a house where a woman leaned against the frame of the open door, while another sat in an upstairs window combing her hair, ‘why would I travel all the way to Canterbury for such work when it’s available on my doorstep? Not that I’m interested in it,’ she added hastily.

Mrs Simmonds wasn’t affronted, but laughed and laid her hand on Lizzie’s arm. ‘My dear, you are exactly as I hoped when I first spotted you in the street. A girl who is not only striking in appearance, but with something to say for herself. My establishment is far removed from such as these. I have a respectable dress shop, and I require a model to show off my designs. You have the face and the figure I have been looking for. I hope you will let me tell you more, so I can tempt you to join me.’

Lizzie, flattered but also flustered, wasn’t sure how to respond.

‘I can see you will need time to consider,’ Mrs Simmonds continued. ‘I’m sure you weren’t expecting such a proposal on your outing this morning. Now, I’ve told you my name but you haven’t introduced yourself.’

Lizzie was strangely reluctant to share such information with a stranger, but she said, ‘Elizabeth. Elizabeth Carey.’ She bit her lip. Perhaps she should have made something up, she thought.

‘And where can I find you, Miss Carey?’

Lizzie had a sudden vision of Mrs Simmonds turning up on the doorstep of number seven Lower Street. It appeared smart enough from the outside but the minute the door opened she would be engulfed by the noisy chaos of the Carey family. They never had visitors who weren’t relatives. Would there even be space to sit down? Lizzie glanced at Mrs Simmonds’s smart costume and reached a decision. ‘It would be better if I could visit you,’ she said. ‘Tomorrow, or the day after?’

‘I’m staying at Throckings Hotel. Meet me there at ten o’clock tomorrow morning. I do hope you’ll make the right decision.’ Mrs Simmonds was brisk in her farewell and walked away without looking back.

Lizzie watched her confident progress along Middle Street and marvelled at the strange course the morning had taken. Then she turned her face towards home. Her mother would wonder where she was. She should have said, ‘No,’ there and then to Mrs Simmonds. Of course she couldn’t take up her offer of employment. How would the family manage without her? But she wanted to savour the sudden hope it had given her, the idea that there was a world beyond Castle Bay, a world in which she could find her place. She could at least hold on to that dream for a few more hours.

A dark cloud, blown in from the sea, had obscured the sun as Lizzie hurried up Lower Street. The first drops of rain began to fall as she opened the gate to number seven and her thoughts went involuntarily to Mrs Simmonds. Would she have reached Throckings Hotel by now, or would her smart costume be spoiled by the rain? If so, it would do nothing to improve her opinion of Castle Bay, Lizzie thought.

She stepped through the front door to be greeted by the sight and sound of her two youngest siblings, Alice and Susan, wailing, a broken doll on the floor in front of them. Mary, the next oldest, cast a glance at Lizzie, then looked at the floor, her bottom lip stuck out. There was no sign of Ruth and Jane, or of their mother, so Lizzie knelt and picked up the doll, a simple one carved from wood by their grandfather, Walter. He had used metal pins to attach the limbs, one of which now lay on the floorboards. The sleeve of the blouse, which Lizzie had stitched from a remnant of one of her own worn-out garments, hung empty.

‘Were you fighting over Arabella?’ Lizzie asked. It was a regular occurrence. Walter had repaired the doll many times, before being struck by the idea of making another so they could have one each. Alas, it had made no difference. Whichever doll was being played with by Alice or Susan became the target of desire by the other. Although, in this case, Mary’s expression suggested she might have been the culprit.

‘Come on, don’t cry. I’ll try to mend her later, and if I can’t do it, we’ll ask Grandpa Walter.’

Lizzie hoped her repair would be successful, for now that Walter had moved away to the countryside and was happily ensconced in a cottage with Eliza Marsh, they saw him far less frequently.

‘Where’s Ma?’ she asked, but receiving no answer she took her basket to the kitchen and began to unpack the few items, adding them to the meagrely stocked shelves. Mark Carey was a fisherman and his income fell far short of that required by a family of eight. Lizzie knew that, along with a great many other men in the town, he took part in smuggling runs, ferrying goods from French ships anchored a distance from the coast of Castle Bay in the safety of the waters known as The Downs. On dark, moonless nights, tubs of brandy and flagons of other spirits, wine, tobacco, tea and coffee were transferred from the vessels to the galleys rowed by the men of Castle Bay. As soon as the boats crunched ashore on the shingle beach, the goods melted away into the myriad cellars of the town.

At its height, the trade had been lucrative and the town had felt almost prosperous. But two events had combined to make smuggling less appealing, and more risky. With the end of the French wars, the soldiers garrisoned in the town had departed, removing a ready market for many of the goods. And the raising of a new force, the coast guard, to tackle the smuggling had proved far more effective than the past efforts of the revenue men. The latter could be paid off; the coast guard were not local and much harder to corrupt.

Tonight’s dinner would be soup and bread, Lizzie thought, the same tomorrow and the next night, unless fortunes changed and the sea provided a bounty of fish. Her thoughts turned to Mrs Carey, Ruth and Jane. Now that the three youngest girls had stopped fighting, the house was very quiet. Surely her mother wouldn’t have gone out and left the younger ones alone at home.

The front door banged and a chatter of excited voices was added to the sniffs she could still hear from Alice and Susan.

‘Ma?’ Lizzie stuck her head around the kitchen door. ‘Where have you been?’

‘Just along the road to Mrs Watson,’ Mrs Carey said. ‘You were such a time and I’d promised to take Ruth and Jane to try on their new dresses.’

Lizzie experienced a surge of irritation. Where was money to be found for new dresses? And why did her mother think it appropriate to leave a five-year-old in charge of a two- and a three-year-old? She felt a niggle of guilt all the same. Had her conversation with Mrs Simmonds delayed her? Surely by no more than a few minutes.

‘Where were you?’ Mrs Carey persisted. ‘Not wasting time with that boy who works for Widow Booth, I hope.’

‘Whatever are you talking about, Ma?’ Lizzie was genuinely confused. Her mother often suspected her of dallying with one or other of the local boys, but Lizzie had no time for them. If she dared contemplate her future, it didn’t consist of following in the footsteps of her parents and filling a house with small children they couldn’t afford. She looked to her older sister, Nell: her husband, Thomas Marsh, at least had prospects. He was well thought of at Coopers Brewery and would undoubtedly be promoted soon. All at once Mrs Simmonds’s unusual proposal, which she had imagined politely rejecting, began to look more enticing.

‘I could have made dresses for Ruth and Jane,’ Lizzie said. ‘Where are we to find the money to pay Mrs Watson? And Mary is too young to be left in charge of Alice and Susan. They had been fighting when I got home and Arabella is broken again.’ She held up the doll.

Her name was far too grand for her appearance – head roughly carved from wood with eyes, lips and hair painted on, the cloth body dressed in a drab brown skirt and once-cream blouse, a plain apron tied around her waist. She ought to be wearing something rather more elegant, like Mrs Simmonds’s outfit, Lizzie thought, and smiled wryly.

She and Nell had been given more elaborate names – Elizabeth and Eleanor – shortened as the other girls began to arrive, to match their simpler names. She had no memory of playing with dolls when she was small. Twelve-year-old Ruth had owned the doll first, naming her and cherishing her. As Arabella had been passed down to the younger siblings, she had become progressively more worn, so that little of her facial expression remained. Lizzie had a feeling that if she attempted to re-draw her features, Alice or Susan would be outraged. They loved their Arabella just as she was, even if their baby lisping had caused them to struggle with her name.

‘Well, Mary will have to get used to taking charge more often,’ Mrs Carey said, with a look of defiance.

Lizzie frowned, uncomprehending.

‘Mrs Watson thinks she can get Ruth and Jane places at the charity school,’ her mother continued proudly. ‘And with another on the way it won’t be a moment too soon.’

Lizzie stared at her mother, struggling to take in her words. Her sisters were going to school, to be educated, when she had never had that luxury, always being called upon to help around the house. And now there was to be another baby to bring up.

Lizzie turned on her heel and went back into the kitchen, slamming the door behind her. She stared out of the window into the yard, filled with a jumble of nets and other equipment that her father didn’t want to leave on the beach by the fishing boat.

She had dismissed Mrs Simmonds’s proposal almost as soon as it was uttered, thinking she couldn’t leave her mother alone to look after so many small children. Yet Mrs Carey seemed quite unworried by her expanding family, no doubt expecting that Lizzie would simply step in to help. Her rising fury made her want to leave the house that very minute and seek out Mrs Simmonds at Throckings Hotel. She would bide her time, though, and make a plan. Any guilt she felt on behalf of her sisters was outweighed by the anger she felt towards her mother and father.

Lizzie’s determination was further fuelled by passing a restless night. All the children slept crammed into one bedroom, which contained a double bed and a single, with barely space to walk between them. The two older ones, Ruth and Jane, had taken possession of the smaller bed, leaving Lizzie to share with Mary, Alice and Susan. The latter had developed a cough, which didn’t trouble her a great deal as she slept through the bouts that struck her every hour or so. Lizzie, however, jerked awake each time, turning over so that Susan wouldn’t cough in her face. Alice and Mary were bound to catch it, she thought. There would be many disturbed nights and tired, crabby days ahead.

She got up with the dawn and went downstairs to rekindle the fire in the range, shivering as she wrapped her shawl around her. March might have brought some bright days but the mornings were still chilly. She stood as close as she could to the range, willing it to heat quickly, and thought about the night just ended and the day ahead. Soon there would be another child to squeeze into the already crowded bedroom Lizzie shared with her siblings. Granted, not for another year or so, for he or she would sleep with Mrs Carey at first. Even so, Lizzie experienced a wave of despair. Her life stretched ahead, days spent in drudgery in Lower Street, or an escape into marriage and a repeat of the same pattern in another house in Castle Bay. A memory of Mrs Simmonds, in her elegant blue-grey costume, came unbidden, along with an image of Lizzie dressed in such an outfit. She almost laughed.

But why not? Why should she have to stay here and endure, when she had been offered the chance to start afresh somewhere new? She felt a little thrill of excitement, then jumped, startled, as her father came into the kitchen through the back door.

‘Daydreaming, Lizzie?’ he asked. He yawned and rubbed his eyes. ‘Make a pot of this, will you?’ He threw a packet of tea onto the table. ‘I’ve a thirst on me, even though I’m in need of my bed.’

‘Have you been out with the boat?’ Lizzie asked, as she took the earthenware teapot down from the shelf and set water to boil.

‘Aye, I have.’ Her father didn’t elaborate, leaving Lizzie unsure as to whether he’d been fishing or on a smuggling run. She was inclined to think the latter, given the packet of tea. It wasn’t something they could often afford to have in the house.

‘You’re a good girl, Lizzie,’ her father said, seating himself at the kitchen table. ‘I don’t know what we’d do without you.’

Lizzie didn’t reply, struck with guilt for the thoughts she’d been having when he’d walked in.

‘I suppose your ma told you about the new one on the way.’

Lizzie nodded, keeping her back to him as she busied herself making the tea.

‘Let’s hope it’s a boy at last, eh? Then we can stop trying.’ Her father chuckled. ‘I need someone to take over the boat when it gets too much for me.’

Lizzie cut a slice from the last remaining stub of the loaf she had bought yesterday and set it before her father. The rest of the family would have to make do. She looked in the housekeeping jar, knowing that, unless a miracle had occurred overnight, there would be nothing in it other than a few coppers.

Her father noticed. ‘I’m hoping to have something for you later,’ he said. ‘There’s money owed to me. I’ll go to the Ship this afternoon.’

Lizzie set her mouth in a grim line to prevent a disbelieving snort escaping her lips. If her father received any payment for whatever he had been up to, she had no doubt that the vast majority would disappear behind the bar of the Ship, or some other tavern, rather than find its way back to Lower Street. She thought to offer to collect what he was owed but knew he would be affronted.

‘No daughter of mine will set foot in the Ship,’ he would declare, ‘or any other tavern at this end of town. They’re full of unsavoury types.’

The irony would be lost on him, Lizzie knew. She saw he was casting around for something to put on his bread. She plonked a jar on the table in front of him: the last of the blackberry jam she had made at the end of the summer, from fruit collected along the path leading to Sandown Castle. She had hidden farthings from the housekeeping jar until she had had enough to buy the sugar she needed to make it. Sugar was a luxury in the Carey household, at least since Nell had left. They had had more money when she was there. Somehow, she had found the time to work behind the bar in the Fountain Inn, and for the Marsh family. She supposed there had been fewer small children at home to be cared for at that time.

Her father had drunk his second cup of tea and picked every crumb of bread from his plate. He pushed back his chair, yawning. ‘I’ll be away to bed, then, Lizzie. Keep those little ’uns quiet.’

Lizzie had just poured tea for herself from the rapidly cooling pot and was looking forward to a few minutes for herself when she heard feet thundering down the wooden stairs.

Alice and Susan burst into the kitchen. ‘Mary’s been sick,’ they announced.

Lizzie made a face. That would mean stripping the bed, and Mary, to wash and dry everything before nightfall: there was no spare linen in the house.

She gulped the tea and set down the cup with a sigh. Then she divided the remaining crust of bread between the two little ones, spreading each piece thinly with a scraping of jam from the jar, before setting off upstairs. Half an hour later, Mary was tucked into Ruth and Jane’s bed, the sheets and her nightgown soaking in a pail. Lizzie kept her fingers crossed that Mary wouldn’t be sick again, as she stirred a pot of watery porridge on the range. If Mrs Carey didn’t come downstairs soon, Lizzie would have to wake her. She was determined to meet Mrs Simmonds at Throckings Hotel at ten o’clock, as arranged. Although what had seemed quite possible yesterday no longer felt so achievable.

The church clock was striking the hour as Lizzie hurried up to the door of Throckings Hotel, then hesitated. She had had to wash and dress in great haste, choosing her second-best dress – wearing her Sunday outfit would have made her mother suspicious if she’d been spotted. Now, faced with entering what passed for the grandest hotel in Castle Bay, her courage almost failed her. But, taking a deep breath, she pushed open the door and marched up to the reception desk as if she was quite used to being in such an establishment.

‘I’m here to see Mrs Simmonds,’ she said. ‘She’s expecting me.’

The desk clerk looked her up and down. Lizzie’s colour rose. She sensed he was getting ready to turn her away. Then, to her relief, she heard Mrs Simmonds’s voice behind her.

‘Miss Carey. You are very punctual. Shall we go through?’ She turned to the clerk. ‘I take it there is a fire in the parlour?’

He nodded, looking a little put out by her manner.

‘We’ll take coffee there,’ Mrs Simmonds continued, and she swept ahead of Lizzie into a room overlooking the sea. Lizzie noticed she was wearing another elegant gown, this time in a deep shade of mulberry. She seated herself at a table in the window and waited for Lizzie to join her.

‘Well, have you considered my proposal?’

Lizzie was prevented from answering by the arrival of a diminutive girl, bearing a tray that was surely too heavy for her. It was laden with a pot of coffee, cups and saucers, a milk jug, sugar bowl, tongs and teaspoons, all of which looked to be in danger of sliding onto the thick rug before she could safely deposit the tray on the table.

Lizzie considered Mrs Simmonds’s question as the girl unloaded her burden and poured the coffee, then went on her way. She still had not reached a decision, having veered one way and the other all the way there. It had been difficult to make her escape – as soon as Mrs Carey had shown her face in the kitchen, Lizzie had announced they had need of bread and, taking the few farthings from the housekeeping pot, she had hurried upstairs to make herself presentable. Mary was sleeping soundly in the single bed so she felt easy about leaving her. She went downstairs on silent feet and slipped out of the front door before Mrs Carey, distracted by Alice and Susan in the kitchen, could protest.

And now here she was, with Mrs Simmonds expecting a decision, while she remained torn between concern for the younger members of her family, and a desperate wish to live a life of her own.

‘I trust you have come to tell me you will be accepting my offer?’ Mrs Simmonds didn’t wait for Lizzie’s response, but carried on. ‘I think you will do very well in my establishment in Canterbury. And, if you do, then I may move you to my other, in London.’ She studied Lizzie’s face closely, causing her to blush. ‘Indeed, I think you will do very well there.’

Lizzie was taken aback. Mrs Simmonds hadn’t mentioned this possibility previously. London sounded both daunting and exciting, especially when she hadn’t been anywhere except Castle Bay in her entire life. But Mrs Simmonds must think she was worthy of such a prospect.

She went on speaking, even though Lizzie still hadn’t found her tongue to answer. ‘I will leave a ticket for you at the Castle Bay Inn, for the Canterbury stage coach tomorrow. Do not leave it too late to travel – I will expect you by the evening. Now, I am returning to Canterbury myself today, and I have things to do first. Take your time and enjoy your coffee.’

Mrs Simmonds, who had barely touched her cup, stood up, causing Lizzie to scramble awkwardly to her feet, too. She nodded at Lizzie and swept from the room. Lizzie sat down again and sipped her coffee, but it was still too hot to drink. So, a decision had been reached, she realised, and she wasn’t the one who had made it. Perhaps it was easier that way.

She should return home. Mrs Carey would demand to know why she had taken so long to make the short journey to the bakery in Middle Street. Yet she was determined to savour the unusual experience of sitting alone, drinking coffee, in such luxurious surroundings. Lizzie gazed around at the panelled walls, the thick rug on the floor. It could have hardly have been more different from the taverns in town that her father frequented. Not that she went into them, but their doors were nearly always open and, through a haze of smoke, Lizzie had glimpsed the scuffed floorboards, the mismatched wooden chairs and tables, the customers in their worn and stained work clothes.

The young girl had reappeared in the doorway, clutching the tray. Clearly, now that Mrs Simmonds had left, it was expected that Lizzie should be on her way, too. Lizzie hastily gulped the coffee, put down the cup and stood up. She hoped Mrs Simmonds had settled the bill, for her few farthings most certainly wouldn’t cover it. She drew herself upright, stuck her chin into the air and marched out, unsmiling, hoping she looked as though she was accustomed to doing such things. Perhaps she would be, she thought, once she was in Canterbury. Only as she left Throckings Hotel and hastened along Beach Street did it occur to her that Mrs Simmonds hadn’t told her where to leave the coach, or the address she would need to go to in Canterbury. Or, indeed, how much she would be paid.

Lizzie, previously undecided about her decision, was now determined to go, despite the uncertainties. Perhaps Mrs Simmonds would leave the address with the ticket for the stage coach, she thought. And she appeared very keen for Lizzie to come and work for her, so presumably she would pay her enough to make it worth her while. She cast aside her misgivings in this way, remembering to stop to buy bread on the way home. She could hear the wails from inside the house before she reached the front door.

Mrs Carey turned an angry face on Lizzie as soon as she entered. ‘Where have you been?’ she demanded. ‘Dallying on the way to the bakery, I’ll be bound.’ She cast a critical glance over her daughter. ‘You look a deal too smart to be setting about the housework. Hoping to impress someone, were you?’

Lizzie fought down the urge to tell her that she had just been in Throckings Hotel, where she was offered a very good position in Canterbury and would soon be wearing garments far more elegant than Mrs Carey could imagine. Something told her that her mother would pour scorn on such an idea. And, in any case, she couldn’t risk alerting her to her plans, or she would find a way to prevent her leaving. Instead she would submit with the best grace possible to the drudgery of another day at number seven Lower Street. She would let imaginings of what lay ahead sustain her, and smile through it all.

‘Mary has been sick again,’ her mother informed her. ‘You’d better go and change the bed, then get those sheets washed and hung out to dry.’

Lizzie settled herself as best she could on the Canterbury stage coach, squashed between a large gentleman and an even larger lady, who had also managed to bring substantial valises on board. These were placed on their knees and looked set to jab Lizzie at every turn in the road. She suspected that the two passengers were related, and had each chosen a window seat so they could get some air. It was going to be a long journey.

Lizzie attempted to sit back on the bench seat, gripping her bundle tightly on her lap. She had packed her meagre belongings in a few snatched moments during the morning, leaving it as late as possible so that no one would notice her Sunday-best dress was no longer hanging from the peg on the wall, or that her hairbrush had vanished from the top of the chest of drawers. Such an observation was unlikely, she knew, but her guilt at what she had planned made her feel as if she had announced, ‘I’m running away,’ to the whole household.

Her heart hammered so hard in her chest that she feared one of the other passengers would surely hear it and comment. She wished the coach would leave. The hour was growing late; she had found it hard to slip away, since although Mary had recovered from her sickness, b. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...