- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

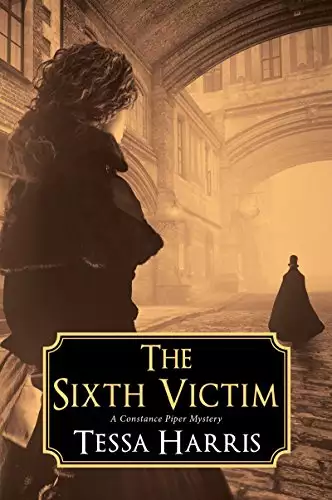

Synopsis

London’s East End, 1888. When darkness falls, terror begins.

The foggy streets of London’s Whitechapel district have become a nocturnal hunting ground for Jack the Ripper, and no woman is safe. Flower girl Constance Piper is not immune to dread, but she is more preoccupied with her own strange experiences of late.

Clairvoyants seem to be everywhere these days. In desperation, even Scotland Yard has turned to them to help apprehend the Ripper. Her mother has found comfort in contacting her late father in a séance. But are such powers real? And could Constance really be possessed of second sight? She longs for the wise counsel of her mentor and champion of the poor, Emily Tindall, but the kind missionary has gone missing.

Following the latest grisly discovery, Constance is contacted by a high-born lady of means who fears the victim may be her missing sister. She implores Constance to use her clairvoyance to help solve the crime, which the press is calling “the Whitechapel Mystery,” attributing the murder to the Ripper.

As Constance becomes embroiled in intrigue far more sinister than she could have imagined, assistance comes in a startling manner that profoundly challenges her assumptions about the nature of reality. She’ll need all the help she can get—because there may be more than one depraved killer out there.

Release date: May 30, 2017

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Sixth Victim

Tessa Harris

There’s blood in the air. Again. They’ve got the scent of it in their nostrils and they’re following it, like wolves honing in for the kill. Only the killing’s already done. It’s the third in a month here, in Whitechapel, and the second in little more than a week and everyone’s in a panic. We’re heading toward the scene, to Hanbury Street. There’s a big swell of us and it’s growing every minute as news seeps out. Shopkeepers gawp, arms crossed, on their steps. Barrow boys are spreading the word. Commercial Street’s always busy at this time of the morning, but now the world and his wife seem to be funneling along the rows of old weavers’ houses in Fournier Street.

Near me, a big man shouts over my head to a friend on the opposite side of the road, cupping his hands round his mouth. “By the cat meat shop!” he yells over the traffic’s din. Past the tight-packed rows of dwellings I go, through Princelet Street, until I reach the place. Sure enough, a big cluster has gathered outside Mrs. Hardiman’s Cat Meat Shop. More and more people are pressing around me now, slavering and baying. They’re craning their necks to see. Some men are even hoisting their little ones on their shoulders to get a look. There are a few newspaper hacks here, too, dressed better than the rest of us, all trying to snuffle up the juicy details.

In the crowd, I spot people I know. There’s Widow Gipps and her creepy half-wit son, Abel. I wouldn’t trust him as far as I could throw him. And Bert Quinn, the knife grinder, skin like a roasted chestnut—he’s here, too. And Mrs. Puddiphatt. She lives on our street. Where there’s trouble, there’s Mrs. Puddiphatt. Sniffs it out, she does, with her big nose. There’s Jews, too. Plenty of Jews. They’re selling jellied eels from a barrow like it’s a carnival, not a killing we’ve all come to see. But I’m looking for Flo, my big sister. I lost her somewhere down Wilkes Street. I bet I know where she’s gone. She’s friends with Sally Richardson, whose ma has a lodging house that backs onto Brown’s Lane. She’ll blag a favor and hope to get a good view of the backyard where they say it happened. Them that lives here are charging sixpence a pop, just for a gander. You can’t blame the poor beggars, but you won’t catch Flo parting with her money when she can get a good view for free.

Truth is, I don’t want to see it. The body, I mean. If it’s anything like the last one, I know I’ll want to retch. I read about Polly Nichols in the papers, see. What did the Star say? She was “ ‘completely disemboweled, with her head nearly gashed from her body.’ ” What sort of maniac could do such a thing? I ask you. And now this one.

A shout down our street woke us all up this morning, Flo and me and Ma. Dawn it was. Barely light. Nippy too. Flo stuck her head out the window. A moment later, she’s back.

“There’s been another!” she tells me, eyes wide as saucers. So she drags me out of my bed, all bleary, and says we’re going to see what’s what. That’s how it is around here. We look out for each other. Everyone knows everyone’s business in these parts, so when one of your neighbors is murdered, then it’s your business, too. And this, this madman—well, he seems not to care who he picks on as long as they’re on the streets.

Maisie Martin was in the Frying Pan on Brick Lane the other night. Flo told me that her friend had been sleeping with her babes not five yards away from where the fiend did his work on poor Polly. She’d heard a scream, then thuds, like someone was hitting her front door. But she froze. She didn’t even dare to look out the window; she was that scared for her little ’uns. And, well, she might’ve been. They found Poll a few paces away, her throat slit and her guts ripped from her body like tripe on a butcher’s block.

Now there’s four women dead since April and the last two’ve been filleted not three streets away from us. When that happens, then you sits up and takes notice, don’t ya? No one’s been done for them, so he’s still on the prowl. There are suspects, of course. They say a Jew did both of the latest ones. Or that it’s the Fenians, them Irish blokes. After Polly, Old Bill started asking us all questions. Did we see anyone acting funny? Did we know them that was done for? But no one’s behind bars, waiting for the hangman. And I don’t mind telling you, that no woman round Whitechapel feels safe.

Anyway, Hanbury Street and Brick Lane is crawling with coppers. There’s a ring of dark blue round Number 29. They’re telling people to keep back. One or two of the rossers are even waving truncheons about, showing they mean business. There’s an ambulance, too. The horses don’t like the crowd. They’re getting restless.

Rumors are racing round like fleas on a dog’s back.

“It’s Dark Annie,” I hear someone growl.

“Annie Chapman?”

“So they say.”

It’s no one I know. I’m feeling relieved when I hear someone yell my name. “Con!” I switch round. “Con!” It’s Flo, a few feet away from me, standing in a doorway. She beckons me to come quick. I break free from the huddle around me.

“Did you see anything?” I ask, scuttling across the street.

She shakes her head. “All I sees was a pair of laced-up boots and red-and-white–striped stockings. Sticking out of a piece of old sack, they was. Then they came to take her off.” She jerks her head over to the waiting ambulance. Her voice is flat, like she’s missed the star act at a variety show. Then, as if she’s trying to make up for her own disappointment, she adds with a cheery shrug: “I ’eard ’er innards ’ave been ripped out, too.”

I cringe at the thought. “You reckon it’s Leather Apron again?” I ask, but before she can answer, a roar goes up. I wheel round to see the crowd craning and pointing. Old Bill’s telling everyone to move back. They’re sliding the body on a stretcher into the ambulance to carry it off. We watch as they shut the doors and slowly the cart pulls off down the street. It takes a while. There’s idiots who cling onto it. Lads mainly. But a few sharp blows with a copper’s truncheon soon sort out that problem and off the ambulance goes to the mortuary.

“Come on,” says Flo, taking my arm. “We’ve seen all we can, for now.”

I’m glad she’s not going to try and sneak another peek of the yard. I’ve had quite enough excitement for one day.

She has not seen me. I wanted to reach out and touch her from here, in the cold shadows, but I did not. Not yet. I’ve been away, you see. Not for long. Five weeks and three days, to be precise. But much has changed since I left. The district is in the grip of a new terror. The horrors that I knew were different in nature, but daily: the starveling in the gutter, the homeless old man dying of cold, the young widow poisoning herself to death on gin. But, unlike poverty, this new horror is not slow and insidious. It’s swift and brutal. It’s barbarous and depraved. It’s murder of the most vile and visceral kind. And, what’s more, it is happening on the streets I know so well. It’s happening in Whitechapel.

The rumors among the crowd are true. Annie Chapman—or Dark Annie as she was known because of her hair color—is the latest victim. I knew her in life. She was a harmless soul. She used to scrape by doing crochet and making artificial flowers. But when she didn’t have enough money to feed herself, she did what most other women in her position had to do, she took to the streets. And, like most women in her position, she also took to the bottle so that the next day she might not remember the sunless alley or the stairwell, nor the grunting and the thrusting and the insults that so often came her way.

Yes, I knew Annie Chapman and I knew she was not well. I could tell by the pallor of her skin and the cough that she so often stifled with the back of her hand that she was suffering from a serious malaise. A few weeks before she was murdered, she came into St. Jude’s. She just sat in a pew at the back and took in the beauty of the place and then she bowed her head. It was hard to tell if it was in prayer or because she felt unwell. Either way, she found a sanctuary in the church. I hope she took away with her a little of the tranquility that she seems to have enjoyed that day. I wish I could have shared that peace with her, too. But it was not to be and the early hours of September 8 were to be her last on earth.

And I witnessed them.

I was in Hanbury Street as dawn was breaking. A stiff wind helped chase away the dark clouds, but still poor Annie had not had a wink of sleep. Turned out of her lodging house because she did not have enough money to pay, she’d roamed the streets all night, touting for business. None had come her way, so far. Barely able to stand because of the giddiness she felt, she’d lurched from one corner to the next. Her poor hands were numb and the nausea was rising in her throat. Little wonder she’d had not a single customer—until then.

From out of the shadows, he appeared and approached her. Of course, she did not know him. To her, he was just another lusty man whose urges needed satisfying. But I knew. I saw her nod in agreement at his words and I saw her being led through a doorway down a long passage. I followed with dread in my heart. I was powerless to help as I saw her walk down the steps into the yard beyond. I watched as she bunched up her skirts and leaned against the fence, splaying her legs in readiness. It was then that he loomed over her and then that I think poor Annie knew something terrible was about to happen. I heard her call, “No!” But it was too late. His hand was already pressed against her mouth. She flailed her arms and scratched at his hands as they tightened round her throat. She must have felt the cold steel on her neck then, because soon the warm syrup of her own blood was coursing through her fingers. I pray she fell insensible immediately. I pray that she was spared any knowledge of what he did next when he lifted her skirts and ripped her with his knife.

After that, I only stayed long enough to see a man open the back door of his home and stumble across the body in his backyard. Wild-eyed, he turned, shambled down the passage, then staggered out onto the street to summon help. And I? I had seen enough, too. But the questions that swirled around in my head reared up once more, just as they did after Martha Tabram and Polly Nichols. Could I have done more to stop this? Should I have done more to stop this? Sometimes I wonder if my own weakness has betrayed my sex, my own cowardice condemned these women? The answer to these questions is that, despite all that has happened to me, I am still powerless to change the minds of evil men. I can only guide those who are willing to listen and through them hope to exert an influence for the good.

The first policeman had been summoned as I took one more look at poor Annie Chapman, her blood still pooling on the ground. There was no more I could do.

Friday, September 14, 1888

“Roses is red. Violets is blue. Three whores is dead. And soon you’ll be, too.”

They’re leering at me, in their ragged clothes, with snotty noses and grins on their dirty faces. None of the draggle-haired nippers can be more than twelve, but I’m scared as hell. I know I shouldn’t be, but their stupid rhyme sends me all ashiver.

“Get away!” I growl through clenched teeth.

“Three whores is dead, and soon you’ll be, too,” they repeat.

“Bugger off!” I lunge at them and shout so loud I startle a passing gent. His monocle pops out of his eye socket in surprise. Anyway, my bawling does the trick. The mangy urchins turn and scuttle off like the sewer rats they are.

This may be swanky Piccadilly, where the ladies and gents dress up to the nines, and it could be a million miles away from Whitechapel, but still my heart’s beating twenty to the dozen and my mouth’s dry as sandpaper. Bold as brass they were, all cocky and brave. And they can be, ’cos they’re not the ones he’s after. He’s after girls and women who work on the streets. The ones who are out at night, drinking their gin by the gill, so they don’t feel the pain as much; so they don’t have to think on what they’ve become.

You’ve got to pity them. I do, at any rate. Miss Tindall’s taught me that. Most of them were once wives or mothers and fate’s dealt them a cruel hand. They’ve all got their hard-luck stories to tell; how their masters had their way with them and landed them with a bun in the oven—I mean, with child—or how they lost their husbands or were beaten by them and forced to leave their homes. Men, eh? Can’t live with them, can’t live without ’em.

I don’t go with ’em, myself. My ma says we’re not that desperate. . . yet. I can tell you there are plenty of poor souls that do round here. Amelia Palmer, Mary Kelly, Pearly Poll. I know ’em all. Salt of the earth, by and large, they are. Granted, some of them are out to fleece their gents for an extra bob or two, but then I can talk. That’s what we do, see. Well, when I says “we,” I mean Flo, really. I don’t like helping her out, only I do, ’cos thieving’s not as bad as selling your body. But I’m still out at night, earning a living, of sorts. That’s why I’m outside this theater tonight with my basket of posies.

In March and April, I sell oranges. They’re the best. You don’t throw them away like you have to with the blooms sometimes. This late in the year, it gets harder. There’s not much left. I managed to buy the last of the lavender today and tied some up in bunches. The ladies like them, they do, to sweeten their cupboards and chests. Moss roses too. Make them up nice myself, I do. I get the rush to tie them for nothing; then I put their own leaves round them. The paper for a dozen costs a penny, sometimes only a ha’penny, if Big Alf’s feeling kind. He’s a gentle giant, he is. Used to work on the railways till his accident, but he’ll do me a deal if I flash my pearly whites. And rosebuds. They always go down well with sweethearts—and when they come to buy from me, Flo slips her hand in their pockets, and relieves them of a few pennies, or of their watches or anything else we can sell. Once or twice, she’s done it too brown and been rumbled. The coppers have gone after her, and almost nabbed her, but somehow she’s always managed to dodge them at the end of the day. She’s slipped into a front room or a shop doorway and just disappeared.

Me? I don’t like that sort of thing. I’m keeping my head down right now. But ’cos—sorry, I should say because; I know my letters, Mr. Bartleby—he’s Ma’s beau—he buys a penny dreadful of an evening and we all sit round and I read out the latest news from the Sun or the Star. I’m the only one in my family who reads proper, you see. My old man, God rest his soul, he taught me how when I was no more than seven. I’d sit on his knee and he’d make the sounds of the letters and point to the page. By nine, I was reading to him; by twelve, I was off with the Pickwick Papers. I used to have a good giggle at that Mr. Pickwick, I did. Miss Tindall, at the church mission, loaned me her books each week: Pilgrim’s Progress and Gulliver’s Travels. I didn’t care for them too much. The words were too fancy, but then she gave me a dictionary and taught me how to look up what I didn’t understand. Then it was like someone switched on one of them big electric lights in the theater and everything became crystal clear. Soon I found books about girls, Clarissa and Vanity Fair. Becky Sharp—now, there was a gal who knew her mind. Miss Tindall said that although I oughtn’t to praise her behavior, it was good for a woman to have—what was the big word she used?—espir . . . aspiration. Yes, that’s it. She told me I’ve been given a great gift and that I’d “set foot on the path to betterment.” She said there’s some that’s happy to stay in the gutter, but there’s a few, like me, who’s looking up at the stars. So I started to help out at Sunday school, teaching the youngsters their letters, and, in return, Miss Tindall, well, she’s been helping me to be more of a lady. You can always tell a lady, Miss Tindall says, and not just by her clothes. It’s the way she walks and holds herself and the way she talks, too. So Miss Tindall started to teach me to talk proper. Or should it be properly? There are all sorts of rules about how you ought to speak if you’ve any hope of being a lady, so I try and follow them. Well, some of the time.

I think I’m doing well. Of course, I slips back to the ol’ Cockney when I’m with my own kind; but when I’ve a mind, I can put on airs and graces as good as Sarah Siddons and the like. The thing is, I ain’t—I haven’t—seen Miss Tindall these past six weeks. She’s not taken Sunday school and no one will tell me where she is. Anyhow, that’s why I pronounce my aitches and say “them,” instead of “’em,” like Flo, when I remember. She says I’m getting stuck-up, but I’m not. I just want a better life, and someday I might get to be a shopgirl and work in Piccadilly at Fortnum & Mason, or at Harrods, and leave Whitechapel behind. Of course, Miss Tindall says, I should set my sights even higher and aim to study at her old Oxford college, Lady Margaret Hall. Well, you’ve got to laugh. But she reckons I can make something of myself, and that means a lot to me. It means I can get out of the East End for a start.

Well, I can tell you, it’s a scary place to be right now. It gives me the creeps, reading out loud ’bout what he done to them poor souls; the last two have been the worst. Some call him the Whitechapel Murderer, or Leather Apron, because he was a nasty piece of work already known round these parts. Everyone thought it was that Jew, John Pizer, but the coppers nabbed him earlier this week and let him go again because he had good alibis. Anyway, I have to read out to Flo and Ma and Mr. Bartleby how he slit Polly Nichols so deep that his knife ripped through her stomach. And, Lord help me, how he made off with Annie’s womb. Imagine that! And I says this out loud and everyone listening goes “errgh” and “aargh,” and then they says “go on” and I’m expected to read it like it was a nursery rhyme or a fairy tale. But it’s not. It’s real and it gets in my head, it does, like a bad dream, and I can’t shake it off.

So that’s how these rascals manage to terrify the living daylights out of me. That’s why I hate walking all the way to the West End to pretend to sell flowers to ladies and gents outside the theaters when all I really wants to do is stay at home with the door bolted. But tonight’s different, because tonight, now I’ve got rid of my flowers and my basket is empty, we’re going to the theater ourselves. I’m just waiting for Flo, you see. Her sweetheart, Danny Dawson, is the doorman at this here Egyptian Hall. He’s greasy as an old frying pan. His hair’s slicked back with oil and his moustache is waxed sharp at the ends. He’s always trying to steal a kiss from Flo—and from me when he’s had a few too many—and I don’t like him. The Lord knows what Flo sees in him. She could have her pick of any man she flutters her peepers at. She’s that pretty. But Flo says she and Danny’ll get wed next year, once they’ve put a bit aside, and then he’ll be family. I’m hoping that means she’ll give up thieving. Ma’ll have one less mouth to feed, at least. Her eyes aren’t good with all the sewing she takes in. She needs to rest them or she’ll go blind.

Anyway, that’s why I’m standing on these theater steps in the West End, under the glare of the streetlamps, surrounded by crowds of people packing the pavements before they go in to watch the show. We’re going to see a famous American illusionist. Mr. Hercat is his name, and we’re in for an evening of Mirth! Mystery! Music!—at least that’s what the poster says. There’s a nip in the air and I pull my shawl around me. But I’m still shaking, not with the cold, or with excitement, but with fear. Them boys have reminded me that afterward Flo and me have got to walk back through Whitechapel in the dark.

“Come on, Con!” Flo says, grabbing me by the arm. She gives me that much of a fright that I gasp. I forget, too, that I usually tell her not to call me that. I always says to her: “My name is Constance.” And she always goes: “La-di-da, fat cigar!” and pulls a face, telling me I’ve got ideas above my station. She says I’m silly to have my dreams and silly to let Miss Tindall turn my head so. She can upset me sometimes. But tonight I’m just glad to see her. I’m glad when she puts her hand in mine, and I’m even gladder that when we go round the back of the hall to the stage door in the alley with all the rubbish and the rats, that it’s Danny waiting for us, his face glistening in the lamplight, and not a man with a knife stepping out of the shadows.

The streets of Whitechapel have been much quieter this week, since the murders. Few respectable women venture out after dark and even men seem more cautious, a little too eager to accompany one another in an unspoken show of solidarity, yet not wishing their eagerness for companionship to be misconstrued as weakness. Into the stead of the common throng step the policemen, the men of the Metropolitan and City of London police forces. They do their shambling best, but it is really not good enough, and at the Whitechapel Workhouse Infirmary the business of life—and death—continues as usual.

It is Friday evening and every Friday evening Terence Cutler, an obstetrician and fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, pays his weekly visit. Tall, in his midthirties and with sandy-colored hair that is thinning slightly, he possesses—on the surface, at least—an air of calm efficiency, which is so often mistaken for arrogance. Normally, he appears a gentleman who is confident of his own professional abilities, although his personal qualities are a little more precarious. His youthful activities with the women he was later to treat have left an unfortunate legacy. On this particular evening, it is evident to me that he is deeply troubled, although not by irksome symptoms of a purely physical nature. The room is cool, verging on cold, but there is sweat on his forehead.

“Just the one tonight, Mrs. Maggs?” he asks as he steps away from the shivering girl lying on the table. Her skirts are rucked up around her waist and her bent legs are spread wide.

The midwife, a solid, woman, with a frizz of gray hair escaping from her dirty cap, is disposing of the contents of a chipped enamel bowl down the sluice.

“Aye, sir,” Mrs. Maggs replies in her brusque Scottish manner. She returns to the girl and lowers her limbs onto the table, one after the other, restoring a vestige of dignity to someone who has lost all else. And there, the patient remains motionless, either too drugged or too afraid to make a move. It is not clear which.

The surgeon glances back, rather wistfully, I think, and studies his charge as she lies submissively, like a sacrificial lamb on an altar. She is a waif and her blond hair, made darker by sweat, is plastered around a small head. Her complexion is almost as white as the wall tiles.

“She’s but a child,” I hear Cutler mutter. His voice is despairing, almost tremulous. I know he is wondering how it ever came to this.

“Aye, sir,” replies Mrs. Maggs, cheerful as a housewife at a market stall. “She’s a wee one. They seem to get younger every year,” she replies, leaning over the girl. She tilts her head in thought, then adds: “It’ll take more than a change in the law to stop it.” A large flap of loose skin hangs down from her jaw, hiding her neck and reminding me of a turkey. It wobbles as she speaks again. “Another drop o’ laudanum’ll see her right.” She produces a dark glass bottle from her apron pocket, jerks round to make sure the surgeon is occupied, then takes a swift swig from it herself before offering it to the girl.

Cutler, his back turned on such misdeeds, shakes his head and glances at his hands. The lines on his palms are red with blood, as if someone has taken a pen and drawn them in ink. The rims around his nails are red, too. He reaches for a brush and begins to scrub them, taking even more than his usual care. It is as if he is trying to slough off something particularly vile. The trouble is, he knows he has become as corrupted as the diseased flesh he so often treats. He had started off with such high ideals. He would rid the world of the scourge of syphilis. But the French malady, despite its Gaelic soubriquet, is not fashionable, at least not among the moneyed classes who could further his career.

Meanwhile, the old midwife pats the girl’s clenched hand as it settles on her chest. “Och! But you’ll live, won’t ya, dearie?” She switches back to the surgeon with a smile. “And you’ll be able to get on your way sooner tonight, sir.”

“What?” replies Cutler, deep in thought.

“You’re finished for tonight.”

“Yes, indeed.” His reply is halfhearted. He does not bother to turn round to address her. Why he would want to go back home sooner defeats him at the moment. There is nothing and no one for whom he needs to return. A well-connected wife had been necessary at the time, so his research into venereal disease, while not stopping, needed to be conducted in secret. Upon his marriage, his papers and the lurid photographs of infected patients, so vital to his research, suddenly became incriminating to the lay eye. He was forced to keep them under lock and key, as if they were pornographic—a guilty and perverted secret.

The midwife’s gray brows dip in reflection as she turns away from the table to busy herself. “No one wants to hang around Whitechapel at the moment.”

“No, indeed,” Cutler agrees. He nods at Mrs. Maggs over his shoulder, then turns back to finish washing his hands with carbolic soap. As he does so, I see his large moustache twitch as if his features have relaxed a little. He seems relieved that he will not be called upon again this evening.

The midwife takes another surreptitious swig of laudanum as if to give herself courage. “These terrible murders are making all of us fret,” she continues. Her tone remains cheerful and I suppose the laudanum is having an effect on her mood.

“I am sure,” Cutler replies without conviction. He is clearly humoring the woman out of his innate politeness. Shaking his hands over the basin, he turns to take the towel left out for him on a nearby rail. The chipped enamel dish has been deposited nearby. I see his eyes collide with it accidentally, then deliberately veer away, his face registering an expression of mild disgust. Next he divests himself of his spattered apron as if it is riddled with plague. Throwing. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...