Page was not found.

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

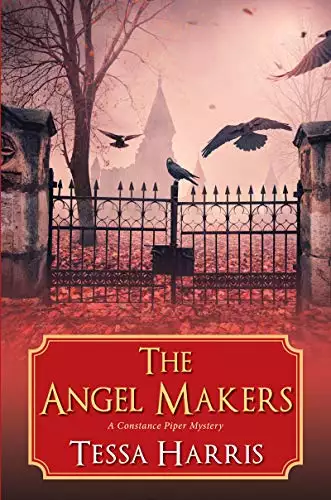

In Victorian England, flower seller Constance Piper goes searching for the truth behind a new rash of murders in London's East End . . .

In November 1888, the specter of Jack the Ripper instills fear in every woman who makes her living on the streets of London. But there are other monsters at large, those who shun fame and secretly claim their victims from among the city's most vulnerable . . .

Options are few for unmarried mothers in Victorian England. To avoid stigma, many find lodging with “baby farmers”—women who agree to care for the infant, or find an adoptive family, in exchange for a fee. Constance Piper, a flower seller gifted with clairvoyance, has become aware of one such baby farmer, Mother Delaney, who promises to help desperate young mothers and place their babies in loving homes. She suspects the truth is infinitely darker.

Guided by the spirit of her late friend, Emily Tindall, Constance gathers evidence about what really goes on behind the walls of Mother Delaney's Poplar house. It's not only innocent children who are at risk. A young prostitute's body is found in mysterious circumstances. With the aid of Detective Constable Hawkins, newly promoted thanks to Constance's help with his last case, Constance links the death to Mother Delaney's vile trade. But the horror is edging closer to home, and even the hangman's noose may not be enough to put this evil to rest . . .

In November 1888, the specter of Jack the Ripper instills fear in every woman who makes her living on the streets of London. But there are other monsters at large, those who shun fame and secretly claim their victims from among the city's most vulnerable . . .

Options are few for unmarried mothers in Victorian England. To avoid stigma, many find lodging with “baby farmers”—women who agree to care for the infant, or find an adoptive family, in exchange for a fee. Constance Piper, a flower seller gifted with clairvoyance, has become aware of one such baby farmer, Mother Delaney, who promises to help desperate young mothers and place their babies in loving homes. She suspects the truth is infinitely darker.

Guided by the spirit of her late friend, Emily Tindall, Constance gathers evidence about what really goes on behind the walls of Mother Delaney's Poplar house. It's not only innocent children who are at risk. A young prostitute's body is found in mysterious circumstances. With the aid of Detective Constable Hawkins, newly promoted thanks to Constance's help with his last case, Constance links the death to Mother Delaney's vile trade. But the horror is edging closer to home, and even the hangman's noose may not be enough to put this evil to rest . . .

Release date: May 29, 2018

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 321

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Angel Makers

Tessa Harris

London, Wednesday, July 17, 1889

It was the footsteps that woke me. From the cradle of my deep sleep, I supposed the noise to be rain splattering the window, or maybe even a trotting horse. Opening my gritty eyes, I looked up at the square of light on our moldy ceiling and thought perhaps I’d dreamed the sound. But then I heard the cry; the cry that we all know round here too well. That’s when I knew it was real. “Murder! Murder!”

Scrambling out of bed, I rushed over to pull up the sash and there he was, in our street, a little nipper, shouting at the top of his voice. “Murder! Murder!” Cupping his hands round his mouth he called out once and then he cried again. He hollered words that turned my blood even colder, and everyone else’s too. “Jack’s back!” he bellowed and a chill ran down my spine quicker than a rat along a drain pipe.

For a moment I was numb. I couldn’t believe it. Still can’t. Just as we were all feeling safe in our beds, just when we dared leave our windows ajar at night on account of the warmer weather, just when we could walk out at twilight again, we hear there’s been another killing. Of course the cry made us all sit up and take notice. If Jack is back, none of us is safe.

Flo was quick off the mark. Pushing me out the way, she shoved her head out the window.

“Where?” she yelled. “Where’s the murder?”

The lad turned and, still running backwards, gulped and yelled up, “Castle Alley, by Goulston Street Wash’ouse.”

Ma shuffled in with her shawl drawn round her shoulders and a frown on her brow. “What’s amiss?” she wheezed, all blurry-eyed.

Flo and me swapped glances. We knew she wouldn’t take it well.

“There’s been another killing,” I said, as soft as I could, but it still didn’t stop her from gasping for air, like a fish out of water. I feared the shock would bring on another attack, and it did. I rushed over to her and sat her down beside me on the bed.

“I’ll go and see what’s what,” Flo told her, pulling on her skirt. She tried to act all cocky, as if she could make things right, but of course she couldn’t. We both knew that if Jack was back to work, then no amount of brave words would help soothe the terror that’d return. There’s been nothing since November; not since Mary Jane Kelly was found on the day of the Lord Mayor’s Parade. She was Jack’s fifth, or some say sixth victim. ’Course after her came poor Rose Mylett. At first we all thought she was one of his too. With the help of my friend Acting Inspector Thaddeus Hawkins I proved Rose’s murder weren’t Jack’s handiwork after all. So that’s why, eight months on from the foulest murder of all, it’s come as the most terrible shock to everyone to think the fiend stalks among us again.

Yes, eight long months have passed since Jack last struck. Eight months in which the people of Whitechapel and beyond have tried to rebuild their lives. Yet the brutal killings still cast their shadow. I well remember the morning they found the body of what everyone prayed would be the Ripper’s last victim; Mary Jane Kelly. In a squalid room in Miller’s Court it was. I was there when the rent collector first put his eye to the broken pane, but couldn’t quite comprehend the scene at first. He’d been banging on the flimsy door for the past few seconds, fearing it might splinter under his fist. He’d even called the tenant’s name. “Mary Kelly. Mary Jane.” He was used to her scams; the way she’d pretend she didn’t know what day of the month it was, or how she’d sometimes just flutter those long lashes of hers and beg a favor. Her wiles were enough to make a grown man weak at the knees. Or how she’d call him “dear Tommy” in that sing-songy voice of hers that reminded him of a sky lark on a spring morning. But six weeks is a long time in any landlord’s book and Mr. McCarthy wasn’t having any more of her shillyshallying, so this time Thomas Bowyer was under instructions to return with the rent, or not at all.

His knocking having met with no response, Bowyer went around the corner of the premises to where he knew the window pane was broken. Carefully he reached through the jagged glass and drew back the curtain so that he could see inside. It was a sight that would come to haunt him for the rest of his days. He withdrew his hand so quickly from the broken pane that his skin was caught and torn by the glass as he staggered back. Yet he did not make a sound, save for a violent retch in the gutter nearby. Despite his dizziness and nausea, he managed to alert his boss to what he had just seen; to the two pieces of cut flesh on the table and to the blood on the floor and to the fact that the body of Mary Jane Kelly, the prettiest and sweetest of the street girls he knew, lay mutilated beyond all recognition.

That was last November. On the ninth day of the month to be precise. Not that time means anything to me. It is but a ticking of a clock. I am no longer of this earth, you see. I am what they call a revenant. I died—or, more accurately, was murdered, because I tried to expose a secret society of powerful men that preyed on my young pupils. I was handed over to a cruel bully, whom I now know went by the name of the Butcher, and paid the ultimate price for my discovery when he cracked my skull against a wall. Now, however, I have returned to right the wrongs committed against me and so many others who cannot defend themselves against the powers which control their lives.

London’s East End, where this shocking crime against Mary Jane Kelly was perpetrated, is where I usually roam. Unseen by nearly all, I am to be found underfoot in the cobbles of Whitechapel, on the panes of grimy glass, in the fabric of people’s clothes, on wood and on brick, even floating on the air you breathe. There are traces of me all around—of what was, what is and what will come—but only the chosen few can sense them. Constance Piper is one of them and I am able to live on through her.

This time the killing’s even closer to home; just a couple of streets away from us. The washhouse is where Ma, Flo and me go for a bath now and again. ’Course we have to go second class: a cold bath and a towel for your penny. Someday I’ll treat myself to first class: that’s two towels and warm water. Someday.

“Let’s get the kettle on,” I say, guiding Ma downstairs. I sit her in our one good, horse-hair armchair by the empty hearth just as Flo steps over the threshold to find out what’s what.

“I won’t be long,” she calls back to Ma, trying to reassure her, only she’s wheezing that much, I’m not sure she’s heard. So we sit and we wait.

Already there’s a dreadful brouhaha outside. People are coming down our way to get to Castle Alley. You wouldn’t ever catch me down that dingy rat hole. Never gets any sun, even when there’s some to be had. In shadow all day, it is. It’s where some of the local costermongers park up their barrows for the night. You get all sorts coming and going and all manner of diseases lurking there, so they say. Some ragamuffins and unfortunates even kip down under the carts. If you can put up with the stink I suppose it’s out of the rain. But I needs hold my breath just when I’m passing, the stench is that bad.

At least half an hour goes by before Flo’s back. She takes off her shawl as she blusters through the front door. “It’s Bedlam out there,” she tells us, like she’s the one who’s having it hard. “There’s crowds all round the mortuary, as well as where she was found.”

It’s been raining in the night and there’s mud on her boots. She’s all flushed as she sits down to ease them off. I’m watching her and I’m waiting for her to say something more. It’s like she’s trying to think of how to get something off her chest. But she just gives me the eye and bites her lip.

“Oh God!” I mutter, watching her stand up real slow, like she’s trying to put off what she knows she must do. “It’s someone we know, ain’t it?” I keep my voice low, but Ma, still in the chair, knows something’s amiss.

“Well, Flo?” she asks, all breathy.

Dread flies up like a black crow from somewhere deep inside me. My whole body tenses as I watch my big sister stand in front of Ma, take a deep breath and say, “Word is it’s Alice Mackenzie.”

Thursday, July 18, 1889

As Acting Inspector Thaddeus Hawkins walks up Commercial Street toward the police station, he carries the weight of the world on his shoulders. His normally quick step is slowed by thought, and his invariably pleasant, yet serious, demeanor has been severely compromised.

It’s nine o’clock in the morning. He managed to grab just a few hours’ sleep in the section house last night. This latest murder has put everyone back on their mettle. All his men had finally returned to their normal beats after the terror that the depraved killings of the previous year had wrought. Petty theft, drunkenness, and the usual abhorrent abuse to which women are continually subjected by their menfolk were all habitual crimes starting to occupy his constables’ time once more. Most of the men were relieved to return to the basic business of policing; the policy of “prevention rather than the cure” is what the new police commissioner, James Monro, is so keen to pursue. But Alice Mackenzie’s murder has certainly set the cat among the proverbial pigeons again.

Nevertheless, despite this latest killing, life continues as normal on Commercial Street.

“Parnell Commission latest. Read all about it!” shouts a young newspaper vendor. Hawkins stops to buy a copy of the Telegraph. He will peruse it later. These days the goings-on at the Parnell Commission appear to have replaced talk of Jack the Ripper in the fashionable clubs and drawing rooms of the West End. It seems the Establishment has put the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell “on trial” for allegedly supporting violence to further the cause of Irish Home Rule. The Times newspaper, Hawkins knew, had published some articles that showed him to condone outrages committed by the Fenian Brotherhood, and these were subsequently proved to be forgeries. Politics is a messy business, the detective knows, but he’ll read about it later.

Folding the newspaper under his arm, Hawkins continues down the road, passing deliveries of fruit and vegetables to the greengrocer and crates of fish to the nearby fishmonger.

“’Morning, Inspector,” greets Mr. Bardolph as he guts a herring on a marble slab outside his shop. His sharp knife slits the fish’s gullet with a ruthless efficiency that is all too familiar to the detective. The sight of the blade triggers an old and unwelcome feeling in him. Although he tries to conceal his unease, the shock comes again, the stab in his abdomen. He’d thought he’d be able to consign that terrible, sickly reaction, which he used to suffer during these awful cases, to the recesses of his memory. But in the past two days those old presentiments of dread and the rising nausea have returned. He knows he must inure himself to them. He touches his hat and manages a smile.

“Good morning, Mr. Bardolph.”

Thaddeus Hawkins is a familiar face to most of the shopkeepers and costermongers round here. He’s made it his business to get to know the local community, to share their concerns and fears. Up until two days ago he’d been convinced that the world had heard the last of this Jack the Ripper. He’d seen for himself the conviction held by Commissioner Monro that Montague Druitt was the fiend behind the killings and that his suicide last December had put paid to his nefarious deeds once and for all. Rumor had it, however, that any public announcement on the subject had been barred by the suspect’s brother. William Druitt, it was said, had threatened that if his brother was exposed, he would reveal that there were homosexuals in high positions in the army, in Parliament, at the bar, and in the Church.

Now, however, with this latest unfortunate’s murder, that whole hypothesis had been thrown into the air. It has come as a huge blow and, Hawkins is convinced, will resurrect the terror felt by so many East End residents last autumn. Of course, it is not yet proven that Alice Mackenzie was felled by the same killer. Indeed, within the force itself, there are conflicting opinions—some say Jack the Ripper is returned; others that this murder is unrelated. Whatever the veracity of either claim, the press is already sharpening its metaphorical knives and pointing them at H Division once more.

Events, however, are about to take an even more challenging twist. Sergeant Halfhide, with his unfeasibly large whiskers and bluff manner, is behind the duty desk as Hawkins walks into the police station.

“’Morning, Inspector,” he greets the young detective, but his eyes, shaded by bushy brows, are brighter than usual. There is something conspiratorial in his look that makes Hawkins linger. And then it comes. A white envelope slides across the counter. “I’m to personally see you get this,” says Halfhide, his tongue suddenly bulging against the inside of his mouth in a show of self-confidence. “Came not an hour ago.”

Hawkins picks up the envelope, looks at the back, and as soon as he registers the crest of the Metropolitan Police, his head jerks up again in shock. “From the commissioner!”

Sergeant Halfhide nods, raising his brows simultaneously. “From the very top, sir.”

Wide-eyed, the young detective also nods and, letter in hand, marches into his office, shutting the door firmly behind him. Such is his curiosity he can’t even wait to sit down. Standing over his desk, he takes a paper knife and slices into the top of the envelope with surgical precision. Extracting the contents, he unfolds the single sheet of paper. The handwritten letter reads thus:

Hawkins leans on his desk and considers this rather unorthodox summons from his superior. He wonders why he, an acting inspector, not even a full-fledged one to boot, should be singled out for such a confidential briefing. His former boss, Inspector Angus McCullen, has been on leave since earlier in the year, citing stress due to the exertions of the Ripper investigations. Yet, there are others far more senior than him: Fred Abberline and Edmund Reid, to name but two, whose knowledge of the Whitechapel murders is just as detailed as his own. Nevertheless, who is he, he asks himself, to turn down such a request? An urgent one at that. Whatever the commissioner has up his sleeve, he clearly doesn’t want to involve any senior officers.

London, Saturday, January 12, 1889

Two blasts. Two blasts from a copper’s whistle is all it takes. I shudder to a halt, my breath burning my throat. Behind me is my ma’s beau, Mr. Bartleby. I hear his heavy footsteps pull up sharp. I turn to see his anxious eyes clamped onto the back of my head; his mouth lost under the thatch of his big moustache. We both know what the whistles mean. They’ve found something. My stomach catapults up into my chest. Two more blasts cut through the fog like cheese wire, then it all kicks off. The air’s filled with the shouts and sounds of men running: a dozen pairs of boots trampling over wet stones.

“Flo!” I call softly at first, then louder. “Flo!” Then again, until I’m screaming her name over the mayhem that’s breaking out all around me. More whistle blasts. More footsteps. More shouts, too.

“Clarke’s Yard!” I hear someone yell.

Clarke’s Yard? I’m knocked off balance. Could she be there? She’s not supposed to be there. Clarke’s Yard is where they found poor Cath Mylett just before Christmas.

We’re out of Whitechapel, in Poplar, up toward East India Docks, but this is still Jack’s patch. There’s some who think it was him who strangled poor Cath just a hundred yards up ahead. I’m not so sure. Knew her, we did. She was Flo’s good friend and we was with her the night she was strangled. But what’s Flo doing up here now?

Mr. B’s caught up and we swap looks. Neither of us says a word before we both break out into a run. The high street looms through the patchy smog. Buildings are blurred and smudged, but we can see a couple of coppers making a dash. They’re heading for the builder’s yard. There’s boarded up shops lining the road, but in between an ironmonger’s and a tobacconist’s I know there’s a narrow alley that leads to workshops and stables at the back. Daytime it’s safe—as safe as anywhere can be in this part of London. Come the night, it’s a different story. It’s where men pay to have their way. That’s where they found poor Cath.

I’m hot and cold at the same time and my heart’s barreling in my chest. The air’s so thick with grit and grime, you could spread it on your bread. I throw a glance back at Mr. Bartleby as I run. He’s no spring chicken and he’s gulping down the dirty murk like it’s going out of fashion.

“Over there!” I pant. I pause for a moment as, narrowing my eyes, I make out people pouring onto the street. The women stand on their doorsteps, arms round their little gals, while the men and boys rush over toward the yard, setting the dogs barking.

I start to drag myself as fast as I can toward the din and the gathering crowd. Mr. B’s doubled over, his palms clamped on his thighs. I can’t wait for him. My dread mounts and I start to pray.

“Please, no. Please let her be all right. Please, Miss Tindall,” I mutter. She was my teacher. She won’t let any harm come to Flo. If it’s in her power to save her, I know she will. Jack shan’t touch a hair on my big sister’s head. Emily Tindall won’t let him. I swear she won’t let him.

I’m almost there, level with the lamppost that casts a grubby yellow glow on the opposite side of the street. I reach the edge of the crowd. The lads with the flaming torches who’ve come over with us from Whitechapel are already there.

I’m glad to see one of them is Gilbert Johns. It was him who cared for me when I fell into a faint in the street a few weeks back. A full head taller than most of them, he is, with forearms like Christmas hams.

“Gilbert! Gilbert!” I cry.

He whips round and latches onto my face. Plowing through the gathering crowd like a big shire horse, he edges toward me.

“Miss Constance.” He’s looming over me, and for a moment I feel safe, but then there’s more shouting and we both see the coppers won’t let no one into the yard. There’s two of them at the mouth, barring the way.

“Keep back!” one of them cries. The other rozzer gets out his truncheon and starts waving it in the air, but it’s too late. One of the Whitechapel lads—one with a torch—makes a break for it and bolts down the alley. The murmurings start to swell and the coppers can’t hold their line. The crowd surges forward, funneling down the passage. Gilbert and me are among them. His arm’s around me. Beside us, a little nipper takes a tumble, but no one stops to pick him up. We push on, like rats along a gutter, but a second later everyone’s stopped in their tracks, not by the rozzers, but by the shout that bellows from one of the lads up ahead. It’s a sound that makes all of us stand stock-still and catch our breaths; it’s a sound that causes time to stop still and all around us fall away. It’s the cry I’ll never forget. It’s the cry of “Murder! Murder!”

You may wish to look away. There is blood. Much blood. It is Florence’s, but I am with her, watching over her. I was here to see the flares from the young man’s torch illuminate the sodden earth and show a steady trickle of syrupy liquid. Blood-soaked stockings are visible where the muddy hem of her skirt has ridden up to her knees. She is slumped against a wall, her head lolled to one side, her legs splayed.

What most of the crowd who’ve clustered in the yard do not yet know, however, is that as well as a stricken young woman, a few yards away there also lies a brutally slain body. Jack is here, indeed, lurking in the shadows, waiting to pounce on his next helpless victim. This is, indeed, his domain. Five he’s killed already. Five he’s cut and gutted. That is why Constance is so desperate to find Florence before he does. But what she is yet to discover is that, this time, the murder victim is not a hapless prostitute, nor, thank God, is it her sister. It is a man. His body has been discovered not fifty paces from where Florence lies, in a blacksmith’s forge. Yet despite his sex, there is a similarity in the manner of killing with the fiend’s alleged female victims. Just like Mary Jane Kelly’s, not two months before, his face has been mutilated beyond recognition.

More constables, never far away in these dark days when terror is stalking the streets, are speeding to the scene. When news of this killing seeps out into the gutter press, there will be another frenzy in the East End, in London, in England, in the world. More lurid headlines will be plastered across newspapers; more accusations of incompetence leveled at the Metropolitan Police and Scotland Yard, and Constance will have to suffer yet more pain and anxiety. For the moment, there is no way out of this quagmire. For the moment, everyone is sucked in. For tonight, you see, they will think the very worst. Tonight they will fear that Jack the Ripper has struck again.

Four weeks earlier, Wednesday, December 19, 1888

“Cheer up, my gal. ’Tis the season and all that!” Flo winks as she pats our friend Cath’s arm, then slugs back her second large port and lemon of the night. Or is it her third? Either way, it’s coming up to Christmas and my big sister’s full of spirit, strong as well as festive, if you take my meaning. So, if a good-looker shows her a sprig of mistletoe, those lips of hers’ll be on him like a limpet. ’Course we know it’s all a show. She’s just putting on a brave face, like the rest of us. It’s six weeks now since Mary Kelly felt his knife, but we know he’s still about.

“Deck them halls, that’s what I say!” Flo slams down her empty glass and nudges me. “Whose round?”

Cath and me stay quiet. She’s no money, and me, I don’t take drinks off strangers. We’re in the George Tavern, on Commercial Road in Poplar, not far from the docks. The pub is full of sailors and dockers, and there’s a lech in the corner who’s barely taken his eyes off us girls. On his hand, he’s got a big tattoo of a naked woman. From the look she gave him earlier, I think he might be one of Cath’s regulars. He catches me eyeing his tattoo and suddenly his leathery lips part and he slides his tongue in between them. He rolls it up at the edges and thrusts it in and out of his mouth. I snatch away my gaze and hear him laugh out loud at my fluster.

It’s coming up to ten o’clock and we ain’t seen a friendly face all evening. It’s not Flo’s usual spit-and-sawdust, but she was stood up by her intended, Daniel Dawson. He’s been called to work late at the Egyptian Hall, with it being the festive season and all that. I’m not sure I believe him. Slippery as an eel, Danny is. If I know his sort, he’ll be out with a girl from the chorus. But Flo’s managed to twist my arm as usual. She’s acted all down in the dumps and persuaded me to come and see what her old pal Cath Mylett is up to.

Cath is what the French might call “petite.” Round here, we’d say she was a sparrow. She’s been working in Poplar this last month. A good few years older than Flo, she is, but they always seemed to have a laugh together. Even named her first daughter after her, she did, but all that was before he came a-calling earlier on this year. It’s like there’s this great shadow cast over London Town and its name is Jack the Ripper. Cath is a working girl, see. In Whitechapel, she’s known as Drunken Lizzie Davis, on account of her being partial to a tipple, or Rose—that’s her favorite, but here in Poplar, she’s changed her working name again, for a fresh start. Fair Alice Downey, they call her. She reckoned she’d be out of Jack’s patch if she went nearer the docks.

Flo thinks Cath’s got a man round these parts, too, but he’s married, so she sees him on the sly. But new man or no, she still has to earn her keep out on the streets.

“Like it over here then, do you?” I ask Cath. She’s not one for the gab, not like our Flo, so I try and make small talk. She shrugs and turns to the direction of the lech.

“Whitechapel or Poplar, one man’s prick is the same anywhere,” she says in a loud voice, so as he can hear. She talks like she’s got dirt in her mouth. “Leastways Jack’s less like to get me ’ere,” she adds.

There’s an odd look in her eye, and when I shoot her a questioning glance, she bends low and points to the side of her boot. I catch sight of the wooden handle of a short knife. I’ve heard a lot of working women are arming themselves with hatpins and the like. And who can blame them? A girl’s got to do all she can to protect herself these days. What’s more, from the look on her face, I know she’d use it, too.

So we’re sitting in the corner, minding our own business, when I see Cath tense. I follow her gaze and who should I see but Mick Donovan, Gilbert Johns’s friend. He’s the Paddy with the funny walk, who worked at Mrs. Hardiman’s Cat Meat Shop. There’s sprigs of sandy hair sprouting under his nose, but it’ll take more than a ’tache to make a man of him. He’s having a word with a bloke at the bar, but as soon as he sees us three gals, he’s over in a flash.

“’Evening, ladies,” says he, like we’re the best of mates. But Cath is in no mood for boys like him, even if he could pay for his pleasure. She gives him the cold shoulder, so his roving eye soon settles on our Flo. Punching above his weight, if you ask me. Nonetheless, in two shakes of a lamb’s tail, he’s offering to buy her a drink.

“Had a win with a filly at Kempton, so I did,” he tells us. He’s a gambler, all right, but I’ve no interest in helping him spend his winnings in case he wants something in return, if you get my drift. Flo, on the other hand, never refuses a free bevy and accepts his offer.

While she’s making chitchat with Mick, Cath and me are left to our own devices. Seems she’s not up for a night on the tiles. She’s edgy and upset about something and keeps looking over to the bloke at the bar, the one with his back to us. The drink’s not working on her like it usually does. Her skin’s all pale and papery and it’s creased between her eyes by a ceaseless frown. This time last year, she lost a baby girl. Hazard of the job, you might say. Sometimes not all the douching in the world will stop one of those blighters hitting the mark, if you’ll pardon my being so frank. But I know she loved this little one—Evie, she called her—just as much as she loved Florence, her first, the one she named after our Flo. But just like with Florence, she had to give her away. Somehow she managed to scrape together a fiver and put the poor mite up for adoption. The minder told her there was a good home for the little soul, but Cath was pining so much that the next day she decided she wanted her back. So she called in, only to find Evie had become an angel overnight. Whooping cough, they told her, even though she seemed heal. . .

It was the footsteps that woke me. From the cradle of my deep sleep, I supposed the noise to be rain splattering the window, or maybe even a trotting horse. Opening my gritty eyes, I looked up at the square of light on our moldy ceiling and thought perhaps I’d dreamed the sound. But then I heard the cry; the cry that we all know round here too well. That’s when I knew it was real. “Murder! Murder!”

Scrambling out of bed, I rushed over to pull up the sash and there he was, in our street, a little nipper, shouting at the top of his voice. “Murder! Murder!” Cupping his hands round his mouth he called out once and then he cried again. He hollered words that turned my blood even colder, and everyone else’s too. “Jack’s back!” he bellowed and a chill ran down my spine quicker than a rat along a drain pipe.

For a moment I was numb. I couldn’t believe it. Still can’t. Just as we were all feeling safe in our beds, just when we dared leave our windows ajar at night on account of the warmer weather, just when we could walk out at twilight again, we hear there’s been another killing. Of course the cry made us all sit up and take notice. If Jack is back, none of us is safe.

Flo was quick off the mark. Pushing me out the way, she shoved her head out the window.

“Where?” she yelled. “Where’s the murder?”

The lad turned and, still running backwards, gulped and yelled up, “Castle Alley, by Goulston Street Wash’ouse.”

Ma shuffled in with her shawl drawn round her shoulders and a frown on her brow. “What’s amiss?” she wheezed, all blurry-eyed.

Flo and me swapped glances. We knew she wouldn’t take it well.

“There’s been another killing,” I said, as soft as I could, but it still didn’t stop her from gasping for air, like a fish out of water. I feared the shock would bring on another attack, and it did. I rushed over to her and sat her down beside me on the bed.

“I’ll go and see what’s what,” Flo told her, pulling on her skirt. She tried to act all cocky, as if she could make things right, but of course she couldn’t. We both knew that if Jack was back to work, then no amount of brave words would help soothe the terror that’d return. There’s been nothing since November; not since Mary Jane Kelly was found on the day of the Lord Mayor’s Parade. She was Jack’s fifth, or some say sixth victim. ’Course after her came poor Rose Mylett. At first we all thought she was one of his too. With the help of my friend Acting Inspector Thaddeus Hawkins I proved Rose’s murder weren’t Jack’s handiwork after all. So that’s why, eight months on from the foulest murder of all, it’s come as the most terrible shock to everyone to think the fiend stalks among us again.

Yes, eight long months have passed since Jack last struck. Eight months in which the people of Whitechapel and beyond have tried to rebuild their lives. Yet the brutal killings still cast their shadow. I well remember the morning they found the body of what everyone prayed would be the Ripper’s last victim; Mary Jane Kelly. In a squalid room in Miller’s Court it was. I was there when the rent collector first put his eye to the broken pane, but couldn’t quite comprehend the scene at first. He’d been banging on the flimsy door for the past few seconds, fearing it might splinter under his fist. He’d even called the tenant’s name. “Mary Kelly. Mary Jane.” He was used to her scams; the way she’d pretend she didn’t know what day of the month it was, or how she’d sometimes just flutter those long lashes of hers and beg a favor. Her wiles were enough to make a grown man weak at the knees. Or how she’d call him “dear Tommy” in that sing-songy voice of hers that reminded him of a sky lark on a spring morning. But six weeks is a long time in any landlord’s book and Mr. McCarthy wasn’t having any more of her shillyshallying, so this time Thomas Bowyer was under instructions to return with the rent, or not at all.

His knocking having met with no response, Bowyer went around the corner of the premises to where he knew the window pane was broken. Carefully he reached through the jagged glass and drew back the curtain so that he could see inside. It was a sight that would come to haunt him for the rest of his days. He withdrew his hand so quickly from the broken pane that his skin was caught and torn by the glass as he staggered back. Yet he did not make a sound, save for a violent retch in the gutter nearby. Despite his dizziness and nausea, he managed to alert his boss to what he had just seen; to the two pieces of cut flesh on the table and to the blood on the floor and to the fact that the body of Mary Jane Kelly, the prettiest and sweetest of the street girls he knew, lay mutilated beyond all recognition.

That was last November. On the ninth day of the month to be precise. Not that time means anything to me. It is but a ticking of a clock. I am no longer of this earth, you see. I am what they call a revenant. I died—or, more accurately, was murdered, because I tried to expose a secret society of powerful men that preyed on my young pupils. I was handed over to a cruel bully, whom I now know went by the name of the Butcher, and paid the ultimate price for my discovery when he cracked my skull against a wall. Now, however, I have returned to right the wrongs committed against me and so many others who cannot defend themselves against the powers which control their lives.

London’s East End, where this shocking crime against Mary Jane Kelly was perpetrated, is where I usually roam. Unseen by nearly all, I am to be found underfoot in the cobbles of Whitechapel, on the panes of grimy glass, in the fabric of people’s clothes, on wood and on brick, even floating on the air you breathe. There are traces of me all around—of what was, what is and what will come—but only the chosen few can sense them. Constance Piper is one of them and I am able to live on through her.

This time the killing’s even closer to home; just a couple of streets away from us. The washhouse is where Ma, Flo and me go for a bath now and again. ’Course we have to go second class: a cold bath and a towel for your penny. Someday I’ll treat myself to first class: that’s two towels and warm water. Someday.

“Let’s get the kettle on,” I say, guiding Ma downstairs. I sit her in our one good, horse-hair armchair by the empty hearth just as Flo steps over the threshold to find out what’s what.

“I won’t be long,” she calls back to Ma, trying to reassure her, only she’s wheezing that much, I’m not sure she’s heard. So we sit and we wait.

Already there’s a dreadful brouhaha outside. People are coming down our way to get to Castle Alley. You wouldn’t ever catch me down that dingy rat hole. Never gets any sun, even when there’s some to be had. In shadow all day, it is. It’s where some of the local costermongers park up their barrows for the night. You get all sorts coming and going and all manner of diseases lurking there, so they say. Some ragamuffins and unfortunates even kip down under the carts. If you can put up with the stink I suppose it’s out of the rain. But I needs hold my breath just when I’m passing, the stench is that bad.

At least half an hour goes by before Flo’s back. She takes off her shawl as she blusters through the front door. “It’s Bedlam out there,” she tells us, like she’s the one who’s having it hard. “There’s crowds all round the mortuary, as well as where she was found.”

It’s been raining in the night and there’s mud on her boots. She’s all flushed as she sits down to ease them off. I’m watching her and I’m waiting for her to say something more. It’s like she’s trying to think of how to get something off her chest. But she just gives me the eye and bites her lip.

“Oh God!” I mutter, watching her stand up real slow, like she’s trying to put off what she knows she must do. “It’s someone we know, ain’t it?” I keep my voice low, but Ma, still in the chair, knows something’s amiss.

“Well, Flo?” she asks, all breathy.

Dread flies up like a black crow from somewhere deep inside me. My whole body tenses as I watch my big sister stand in front of Ma, take a deep breath and say, “Word is it’s Alice Mackenzie.”

Thursday, July 18, 1889

As Acting Inspector Thaddeus Hawkins walks up Commercial Street toward the police station, he carries the weight of the world on his shoulders. His normally quick step is slowed by thought, and his invariably pleasant, yet serious, demeanor has been severely compromised.

It’s nine o’clock in the morning. He managed to grab just a few hours’ sleep in the section house last night. This latest murder has put everyone back on their mettle. All his men had finally returned to their normal beats after the terror that the depraved killings of the previous year had wrought. Petty theft, drunkenness, and the usual abhorrent abuse to which women are continually subjected by their menfolk were all habitual crimes starting to occupy his constables’ time once more. Most of the men were relieved to return to the basic business of policing; the policy of “prevention rather than the cure” is what the new police commissioner, James Monro, is so keen to pursue. But Alice Mackenzie’s murder has certainly set the cat among the proverbial pigeons again.

Nevertheless, despite this latest killing, life continues as normal on Commercial Street.

“Parnell Commission latest. Read all about it!” shouts a young newspaper vendor. Hawkins stops to buy a copy of the Telegraph. He will peruse it later. These days the goings-on at the Parnell Commission appear to have replaced talk of Jack the Ripper in the fashionable clubs and drawing rooms of the West End. It seems the Establishment has put the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell “on trial” for allegedly supporting violence to further the cause of Irish Home Rule. The Times newspaper, Hawkins knew, had published some articles that showed him to condone outrages committed by the Fenian Brotherhood, and these were subsequently proved to be forgeries. Politics is a messy business, the detective knows, but he’ll read about it later.

Folding the newspaper under his arm, Hawkins continues down the road, passing deliveries of fruit and vegetables to the greengrocer and crates of fish to the nearby fishmonger.

“’Morning, Inspector,” greets Mr. Bardolph as he guts a herring on a marble slab outside his shop. His sharp knife slits the fish’s gullet with a ruthless efficiency that is all too familiar to the detective. The sight of the blade triggers an old and unwelcome feeling in him. Although he tries to conceal his unease, the shock comes again, the stab in his abdomen. He’d thought he’d be able to consign that terrible, sickly reaction, which he used to suffer during these awful cases, to the recesses of his memory. But in the past two days those old presentiments of dread and the rising nausea have returned. He knows he must inure himself to them. He touches his hat and manages a smile.

“Good morning, Mr. Bardolph.”

Thaddeus Hawkins is a familiar face to most of the shopkeepers and costermongers round here. He’s made it his business to get to know the local community, to share their concerns and fears. Up until two days ago he’d been convinced that the world had heard the last of this Jack the Ripper. He’d seen for himself the conviction held by Commissioner Monro that Montague Druitt was the fiend behind the killings and that his suicide last December had put paid to his nefarious deeds once and for all. Rumor had it, however, that any public announcement on the subject had been barred by the suspect’s brother. William Druitt, it was said, had threatened that if his brother was exposed, he would reveal that there were homosexuals in high positions in the army, in Parliament, at the bar, and in the Church.

Now, however, with this latest unfortunate’s murder, that whole hypothesis had been thrown into the air. It has come as a huge blow and, Hawkins is convinced, will resurrect the terror felt by so many East End residents last autumn. Of course, it is not yet proven that Alice Mackenzie was felled by the same killer. Indeed, within the force itself, there are conflicting opinions—some say Jack the Ripper is returned; others that this murder is unrelated. Whatever the veracity of either claim, the press is already sharpening its metaphorical knives and pointing them at H Division once more.

Events, however, are about to take an even more challenging twist. Sergeant Halfhide, with his unfeasibly large whiskers and bluff manner, is behind the duty desk as Hawkins walks into the police station.

“’Morning, Inspector,” he greets the young detective, but his eyes, shaded by bushy brows, are brighter than usual. There is something conspiratorial in his look that makes Hawkins linger. And then it comes. A white envelope slides across the counter. “I’m to personally see you get this,” says Halfhide, his tongue suddenly bulging against the inside of his mouth in a show of self-confidence. “Came not an hour ago.”

Hawkins picks up the envelope, looks at the back, and as soon as he registers the crest of the Metropolitan Police, his head jerks up again in shock. “From the commissioner!”

Sergeant Halfhide nods, raising his brows simultaneously. “From the very top, sir.”

Wide-eyed, the young detective also nods and, letter in hand, marches into his office, shutting the door firmly behind him. Such is his curiosity he can’t even wait to sit down. Standing over his desk, he takes a paper knife and slices into the top of the envelope with surgical precision. Extracting the contents, he unfolds the single sheet of paper. The handwritten letter reads thus:

Hawkins leans on his desk and considers this rather unorthodox summons from his superior. He wonders why he, an acting inspector, not even a full-fledged one to boot, should be singled out for such a confidential briefing. His former boss, Inspector Angus McCullen, has been on leave since earlier in the year, citing stress due to the exertions of the Ripper investigations. Yet, there are others far more senior than him: Fred Abberline and Edmund Reid, to name but two, whose knowledge of the Whitechapel murders is just as detailed as his own. Nevertheless, who is he, he asks himself, to turn down such a request? An urgent one at that. Whatever the commissioner has up his sleeve, he clearly doesn’t want to involve any senior officers.

London, Saturday, January 12, 1889

Two blasts. Two blasts from a copper’s whistle is all it takes. I shudder to a halt, my breath burning my throat. Behind me is my ma’s beau, Mr. Bartleby. I hear his heavy footsteps pull up sharp. I turn to see his anxious eyes clamped onto the back of my head; his mouth lost under the thatch of his big moustache. We both know what the whistles mean. They’ve found something. My stomach catapults up into my chest. Two more blasts cut through the fog like cheese wire, then it all kicks off. The air’s filled with the shouts and sounds of men running: a dozen pairs of boots trampling over wet stones.

“Flo!” I call softly at first, then louder. “Flo!” Then again, until I’m screaming her name over the mayhem that’s breaking out all around me. More whistle blasts. More footsteps. More shouts, too.

“Clarke’s Yard!” I hear someone yell.

Clarke’s Yard? I’m knocked off balance. Could she be there? She’s not supposed to be there. Clarke’s Yard is where they found poor Cath Mylett just before Christmas.

We’re out of Whitechapel, in Poplar, up toward East India Docks, but this is still Jack’s patch. There’s some who think it was him who strangled poor Cath just a hundred yards up ahead. I’m not so sure. Knew her, we did. She was Flo’s good friend and we was with her the night she was strangled. But what’s Flo doing up here now?

Mr. B’s caught up and we swap looks. Neither of us says a word before we both break out into a run. The high street looms through the patchy smog. Buildings are blurred and smudged, but we can see a couple of coppers making a dash. They’re heading for the builder’s yard. There’s boarded up shops lining the road, but in between an ironmonger’s and a tobacconist’s I know there’s a narrow alley that leads to workshops and stables at the back. Daytime it’s safe—as safe as anywhere can be in this part of London. Come the night, it’s a different story. It’s where men pay to have their way. That’s where they found poor Cath.

I’m hot and cold at the same time and my heart’s barreling in my chest. The air’s so thick with grit and grime, you could spread it on your bread. I throw a glance back at Mr. Bartleby as I run. He’s no spring chicken and he’s gulping down the dirty murk like it’s going out of fashion.

“Over there!” I pant. I pause for a moment as, narrowing my eyes, I make out people pouring onto the street. The women stand on their doorsteps, arms round their little gals, while the men and boys rush over toward the yard, setting the dogs barking.

I start to drag myself as fast as I can toward the din and the gathering crowd. Mr. B’s doubled over, his palms clamped on his thighs. I can’t wait for him. My dread mounts and I start to pray.

“Please, no. Please let her be all right. Please, Miss Tindall,” I mutter. She was my teacher. She won’t let any harm come to Flo. If it’s in her power to save her, I know she will. Jack shan’t touch a hair on my big sister’s head. Emily Tindall won’t let him. I swear she won’t let him.

I’m almost there, level with the lamppost that casts a grubby yellow glow on the opposite side of the street. I reach the edge of the crowd. The lads with the flaming torches who’ve come over with us from Whitechapel are already there.

I’m glad to see one of them is Gilbert Johns. It was him who cared for me when I fell into a faint in the street a few weeks back. A full head taller than most of them, he is, with forearms like Christmas hams.

“Gilbert! Gilbert!” I cry.

He whips round and latches onto my face. Plowing through the gathering crowd like a big shire horse, he edges toward me.

“Miss Constance.” He’s looming over me, and for a moment I feel safe, but then there’s more shouting and we both see the coppers won’t let no one into the yard. There’s two of them at the mouth, barring the way.

“Keep back!” one of them cries. The other rozzer gets out his truncheon and starts waving it in the air, but it’s too late. One of the Whitechapel lads—one with a torch—makes a break for it and bolts down the alley. The murmurings start to swell and the coppers can’t hold their line. The crowd surges forward, funneling down the passage. Gilbert and me are among them. His arm’s around me. Beside us, a little nipper takes a tumble, but no one stops to pick him up. We push on, like rats along a gutter, but a second later everyone’s stopped in their tracks, not by the rozzers, but by the shout that bellows from one of the lads up ahead. It’s a sound that makes all of us stand stock-still and catch our breaths; it’s a sound that causes time to stop still and all around us fall away. It’s the cry I’ll never forget. It’s the cry of “Murder! Murder!”

You may wish to look away. There is blood. Much blood. It is Florence’s, but I am with her, watching over her. I was here to see the flares from the young man’s torch illuminate the sodden earth and show a steady trickle of syrupy liquid. Blood-soaked stockings are visible where the muddy hem of her skirt has ridden up to her knees. She is slumped against a wall, her head lolled to one side, her legs splayed.

What most of the crowd who’ve clustered in the yard do not yet know, however, is that as well as a stricken young woman, a few yards away there also lies a brutally slain body. Jack is here, indeed, lurking in the shadows, waiting to pounce on his next helpless victim. This is, indeed, his domain. Five he’s killed already. Five he’s cut and gutted. That is why Constance is so desperate to find Florence before he does. But what she is yet to discover is that, this time, the murder victim is not a hapless prostitute, nor, thank God, is it her sister. It is a man. His body has been discovered not fifty paces from where Florence lies, in a blacksmith’s forge. Yet despite his sex, there is a similarity in the manner of killing with the fiend’s alleged female victims. Just like Mary Jane Kelly’s, not two months before, his face has been mutilated beyond recognition.

More constables, never far away in these dark days when terror is stalking the streets, are speeding to the scene. When news of this killing seeps out into the gutter press, there will be another frenzy in the East End, in London, in England, in the world. More lurid headlines will be plastered across newspapers; more accusations of incompetence leveled at the Metropolitan Police and Scotland Yard, and Constance will have to suffer yet more pain and anxiety. For the moment, there is no way out of this quagmire. For the moment, everyone is sucked in. For tonight, you see, they will think the very worst. Tonight they will fear that Jack the Ripper has struck again.

Four weeks earlier, Wednesday, December 19, 1888

“Cheer up, my gal. ’Tis the season and all that!” Flo winks as she pats our friend Cath’s arm, then slugs back her second large port and lemon of the night. Or is it her third? Either way, it’s coming up to Christmas and my big sister’s full of spirit, strong as well as festive, if you take my meaning. So, if a good-looker shows her a sprig of mistletoe, those lips of hers’ll be on him like a limpet. ’Course we know it’s all a show. She’s just putting on a brave face, like the rest of us. It’s six weeks now since Mary Kelly felt his knife, but we know he’s still about.

“Deck them halls, that’s what I say!” Flo slams down her empty glass and nudges me. “Whose round?”

Cath and me stay quiet. She’s no money, and me, I don’t take drinks off strangers. We’re in the George Tavern, on Commercial Road in Poplar, not far from the docks. The pub is full of sailors and dockers, and there’s a lech in the corner who’s barely taken his eyes off us girls. On his hand, he’s got a big tattoo of a naked woman. From the look she gave him earlier, I think he might be one of Cath’s regulars. He catches me eyeing his tattoo and suddenly his leathery lips part and he slides his tongue in between them. He rolls it up at the edges and thrusts it in and out of his mouth. I snatch away my gaze and hear him laugh out loud at my fluster.

It’s coming up to ten o’clock and we ain’t seen a friendly face all evening. It’s not Flo’s usual spit-and-sawdust, but she was stood up by her intended, Daniel Dawson. He’s been called to work late at the Egyptian Hall, with it being the festive season and all that. I’m not sure I believe him. Slippery as an eel, Danny is. If I know his sort, he’ll be out with a girl from the chorus. But Flo’s managed to twist my arm as usual. She’s acted all down in the dumps and persuaded me to come and see what her old pal Cath Mylett is up to.

Cath is what the French might call “petite.” Round here, we’d say she was a sparrow. She’s been working in Poplar this last month. A good few years older than Flo, she is, but they always seemed to have a laugh together. Even named her first daughter after her, she did, but all that was before he came a-calling earlier on this year. It’s like there’s this great shadow cast over London Town and its name is Jack the Ripper. Cath is a working girl, see. In Whitechapel, she’s known as Drunken Lizzie Davis, on account of her being partial to a tipple, or Rose—that’s her favorite, but here in Poplar, she’s changed her working name again, for a fresh start. Fair Alice Downey, they call her. She reckoned she’d be out of Jack’s patch if she went nearer the docks.

Flo thinks Cath’s got a man round these parts, too, but he’s married, so she sees him on the sly. But new man or no, she still has to earn her keep out on the streets.

“Like it over here then, do you?” I ask Cath. She’s not one for the gab, not like our Flo, so I try and make small talk. She shrugs and turns to the direction of the lech.

“Whitechapel or Poplar, one man’s prick is the same anywhere,” she says in a loud voice, so as he can hear. She talks like she’s got dirt in her mouth. “Leastways Jack’s less like to get me ’ere,” she adds.

There’s an odd look in her eye, and when I shoot her a questioning glance, she bends low and points to the side of her boot. I catch sight of the wooden handle of a short knife. I’ve heard a lot of working women are arming themselves with hatpins and the like. And who can blame them? A girl’s got to do all she can to protect herself these days. What’s more, from the look on her face, I know she’d use it, too.

So we’re sitting in the corner, minding our own business, when I see Cath tense. I follow her gaze and who should I see but Mick Donovan, Gilbert Johns’s friend. He’s the Paddy with the funny walk, who worked at Mrs. Hardiman’s Cat Meat Shop. There’s sprigs of sandy hair sprouting under his nose, but it’ll take more than a ’tache to make a man of him. He’s having a word with a bloke at the bar, but as soon as he sees us three gals, he’s over in a flash.

“’Evening, ladies,” says he, like we’re the best of mates. But Cath is in no mood for boys like him, even if he could pay for his pleasure. She gives him the cold shoulder, so his roving eye soon settles on our Flo. Punching above his weight, if you ask me. Nonetheless, in two shakes of a lamb’s tail, he’s offering to buy her a drink.

“Had a win with a filly at Kempton, so I did,” he tells us. He’s a gambler, all right, but I’ve no interest in helping him spend his winnings in case he wants something in return, if you get my drift. Flo, on the other hand, never refuses a free bevy and accepts his offer.

While she’s making chitchat with Mick, Cath and me are left to our own devices. Seems she’s not up for a night on the tiles. She’s edgy and upset about something and keeps looking over to the bloke at the bar, the one with his back to us. The drink’s not working on her like it usually does. Her skin’s all pale and papery and it’s creased between her eyes by a ceaseless frown. This time last year, she lost a baby girl. Hazard of the job, you might say. Sometimes not all the douching in the world will stop one of those blighters hitting the mark, if you’ll pardon my being so frank. But I know she loved this little one—Evie, she called her—just as much as she loved Florence, her first, the one she named after our Flo. But just like with Florence, she had to give her away. Somehow she managed to scrape together a fiver and put the poor mite up for adoption. The minder told her there was a good home for the little soul, but Cath was pining so much that the next day she decided she wanted her back. So she called in, only to find Evie had become an angel overnight. Whooping cough, they told her, even though she seemed heal. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved