- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

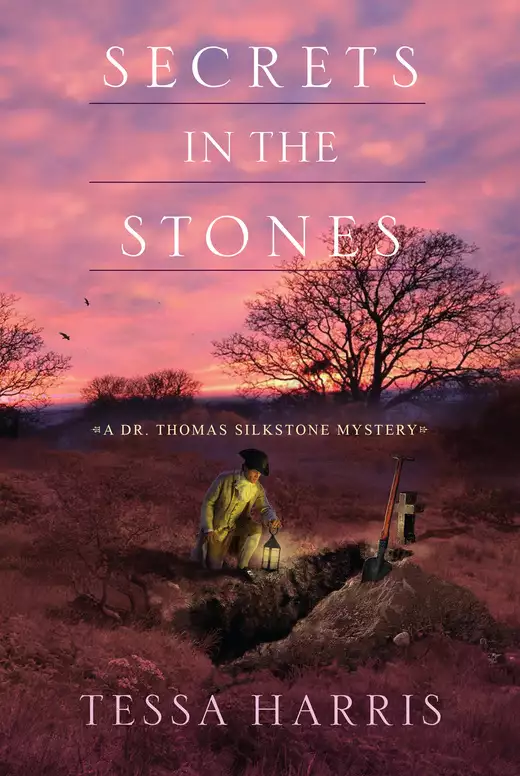

Synopsis

Within the mysteries of the body, especially those who have been murdered, eighteenth-century anatomist Dr. Thomas Silkstone specializes in uncovering the tell-tale clues that lead toward justice.

Newly released from the notorious asylum known as Bedlam, Lady Lydia Farrell finds herself in an equally terrifying position—as a murder suspect—when she stumbles upon the mutilated body of Sir Montagu Malthus in his study at Boughton Hall.

Meanwhile, Dr. Thomas Silkstone has been injured in a duel with a man who may or may not have committed the grisly deed of which Lydia is accused. Despite his injury, Thomas hopes to clear his beloved’s good name by conducting a postmortem on the victim. With a bit of detective work, he learns that Montagu’s throat was slit by no ordinary blade, rather a ceremonial Sikh dagger from India that may be connected to the fabled lost mines of Golconda.

From the mysterious disappearance of a cursed diamond buried with Lydia’s dead husband to the undying legend of a hidden treasure map, Thomas must follow a trail of foreign dignitaries, royal agents, and even more victims to unveil the sinister and shocking secrets in the stones.

Release date: February 23, 2016

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Secrets in the Stones

Tessa Harris

Bava Lakhani was the bania’s name. He was a Gujarati merchant who’d always lived by his wits. He’d known he was taking a gamble, but in a land where fanciful stories grew like pomegranates, he was certain this legend was seeded in truth. For years he’d acted as a middleman between the jagirdars who owned the diamond mines and the Europeans. He would be the first to admit that he did not always play by the rules, the few that there were. Yet the gods had smiled on him so far. The French, the Dutch, the Portuguese, and, of course, the English all knew him to supply a good bulse. They trusted him to select a few fine stones among those of poorer quality and to ask a fair price. When they opened the small purses, they were seldom disappointed: bloodred rubies, cobalt blue sapphires, and, of course, diamonds. Always diamonds. But what he had now was far too valuable to be included in an ordinary packet. What he had now might, just might, be a legend about to be uncovered, waiting to dazzle, delight, and amaze with its fantastical brilliance once it had been cut. What he had now might be worthy to grace the collections of the crowned heads of Europe, who would, no doubt, be willing to pay a most generous price for the privilege.

Yes, there was a risk. There always was, but this risk was bigger than all the swollen bulbs of the old rulers’ tombs put together. And now it was looming over him like a monstrous cobra, readying itself to strike. There’d been an edict. Somehow, word had got out. Somehow the nizam’s vakil had discovered that a miner had not declared his find and had escaped with a huge gemstone from the nearby diamond fields. The miner, a Dalit of the lowest caste, had come to him, and he, Bava Lakhani, had agreed to act for him. But the law was plain. Anyone who found a diamond of more than ten carats was required to hand it over to the governor of the mine. And that law had been violated. The Dalit risked death, and so, of course, did he. He knew that, should they be caught, their executions, the more torturous and gruesome the better, would serve as an example to others who might think of following in their wake. He tugged at his enormous moustache. The thought of his own death sent a runnel of cold sweat coursing down his back and set his heart beating as fast as a tabla drum. Now he must do, or die.

So secret was the mission and so precious the cargo that the transaction had to take place after dark. And how dark it was. Night coated the city’s minarets and spandrels like melted tar. The air was close and the sky pregnant with monsoon rain. Everyone knew the Lord Indra would make the clouds burst any day now. Even though he was a good distance away, the bania could see the guards swarming like locusts on the poor quarter that oozed like a festering sore inside the walls. This was where the mosquitoes and rats were the fattest and the residents the thinnest. The stench was always bad, but at the end of the dry season, it was almost unbearable. Dust choked the narrow streets. And now it was mixed with something else. Fear. He could hear the shouts and screams, too. He knew the guards were approaching fast.

Scrambling down from the wall, the merchant nodded to his naukar. The servant, spindly as a spider, waited below, standing by a handcart that held a large hessian sack. The trader’s gaze settled on the bundle. He gave it an odd look, taking a deep breath as he did so. The deal he was about to broker could mean life or death. The exchange he was about to undertake would seal not just his own fate but that of his only son and his sons, too.

“Come, Manjeet,” he whispered. “We must hurry.”

The moment after the shot tore through the air there was silence. Silence and smoke. It was as if time itself stood still, caught up in the haze of gunpowder, watching to see what would happen. No one had to wait long. The man’s mouth fell agape, and he gasped for the air that was already escaping from his punctured breast. He reeled backward, clutching his chest, then dropped, like a stone, to the ground.

“No. Please, God. No!” cried Lady Lydia Farrell. She rushed forward, careening down the hollow, followed by her maid, Eliza. When she reached the limp body, she slumped to her knees on the dew-sodden grass. A red stain was blooming on the man’s chest. To her horror, she had seen the well-aimed shot hit Dr. Thomas Silkstone.

The apothecary, Mr. Peabody, was the doctor’s second at the duel and the first to reach him. Lydia found him pressing hard on Thomas’s breastbone, trying to stop the dark patch from growing. Jacob Lovelock, the groom, had been waiting with the carriage. As soon as he’d seen the doctor fall, he’d jumped down and begun to run over, too.

“Tell me he is not dead,” Lydia whispered in disbelief. “He cannot be dead.” She reached over and clutched Thomas’s cold hand. Then her own heart missed a beat as she watched the apothecary rip open the bloodstained shirt to reveal the wound.

Mr. Peabody looked up. Even though it was a chilly morning, the little man’s face was glistening with sweat. Lowering his head, he put his ear to Thomas’s mouth, then felt for a pulse in his neck. “He lives,” he told her after a moment. “But only just.”

Lydia felt panic strangle her voice. “He can’t die. He can’t,” she croaked. Eliza, fighting back her own tears, put an arm around her mistress, but Lydia would have none of it. She shrugged her off. “What must we do?” she asked Mr. Peabody.

“We must get him to the carriage, my lady,” he replied.

The morning light was pearly, but a blanket of mist still hugged the ground and Lydia suddenly became aware of men’s voices and the sound of horses. She struggled to her feet and could just make out a carriage on the opposite side of the hollow. A whip cracked and the carriage sped off, heading away from the common.

Jacob Lovelock saw it, too. “Coward!” he cried. “You bastard!” He coughed up a gob of spittle and sent it arcing in the carriage’s direction.

The Right Honorable Nicholas Lupton was leaving the scene in all haste. It was he who had challenged the doctor to the duel. It was he who had fired the shot. And it was he who would face a murder charge if his opponent died.

“He’ll not get away with it, m’lady,” yelled the pock-marked groom, approaching fast.

Seeing her former steward make good his getaway, Lydia also felt the anger rise in her. Like the rat she knew him to be, he was deserting the scene, leaving his rival to die. She also knew her ire needed to be channeled. Now she must devote all her energies to saving Thomas and there was no time to waste.

“Jacob!” she cried to Lovelock. “Help here!” She pointed to Thomas lying motionless in Mr. Peabody’s arms. “We need to get Dr. Silkstone to the Three Tuns.”

A breathless Lovelock nodded and slid his arms under Thomas’s legs.

“Be careful,” Mr. Peabody instructed as he hooked his own hands under his patient’s arms. Together the two men lifted him up.

“But he will live?” Lydia asked the apothecary as he staggered under Thomas’s weight. Eliza steadied her mistress as they headed for the carriage.

Mr. Peabody, his face still grave, grunted, struggling with his burden. “We can but hope, your ladyship, but he needs great care,” he told her.

Reeling across the wet grass, the two men arrived at the carriage and heaved their patient inside, laying him lengthways on a seat. The women followed and Eliza found a blanket to lay over him. Suddenly Thomas started to shake violently, and Lydia shot a horrified look at the apothecary.

“We must get him to the inn,” said Mr. Peabody, feeling the pulse once more. “The professor should be there soon.”

“The professor?” asked Lydia, frowning.

“Professor Hascher, from Oxford,” replied the apothecary. “He will be on his way.”

Puzzled, Lydia shook her head. News of the imminent arrival of Thomas’s anatomist friend from Oxford, although most welcome, confused her. “But how did he . . . ?”

Mr. Peabody’s eyes slid away from hers. “Dr. Silkstone made plans, m’lady,” he said, returning to his charge and pressing on the wound.

“Plans?” repeated Lydia. “What sort of plans?”

Still not lifting his gaze, the apothecary bit his lip, as if trying to stop himself from divulging a secret.

“What sort of plans, Mr. Peabody?” she insisted.

The apothecary shook his head, and then regarded her for a moment.

“The doctor did not accept Mr. Lupton’s challenge lightly,” he began cryptically.

“What do you mean?” Lydia was growing increasingly irritated.

“I mean he conceived a way to thwart any possible injury, m’lady.”

Lydia shook her head. “You are talking in riddles,” she told him. “Please be plain.”

The apothecary sighed, as if acknowledging defeat. “The doctor asked the blacksmith to forge him a light cuirass to repel the lead shot, m’lady.”

“A cuirass!” exclaimed Lydia. “You mean armor?”

Peabody nodded. “I do, m’lady.” He pointed to the bloody wound, and Lydia forced herself to look closer. She could see what he meant. There seemed to be some sort of metal sheeting under Thomas’s shirt. “He also wore a layer of thick horsehair wadding beneath.” The apothecary directed his gaze to a ball of coarse threads, now soaked in blood. “He hoped the lead shot would fail to penetrate the breastplate.”

Lydia’s red-rimmed eyes opened wide. “I see,” she muttered.

Mr. Peabody shook his head. “Sadly, m’lady, the shot has clearly pierced the armor.”

“But you say Professor Hascher is on his way!” There was a note of hope in Lydia’s voice. She should have known that Thomas would not leave it to chance to dodge Lupton’s shot. He was organized, meticulous, reasoned. He would not allow fortune to dictate his fate. There had been method in his apparent madness in accepting the challenge. But that method had most certainly failed him. She gazed at Thomas’s deathly pale face and took his hand in hers once more. “Let us pray he can be saved,” she whispered.

Back at Boughton Hall, Sir Montagu Malthus, the custodian of Lady Lydia’s estate and official guardian to her young son and heir, Richard, was breakfasting in the morning room. A great raven of a man, and one of the finest lawyers in the land, he also carried a very personal grudge. He had made it his mission to prevent Lydia from marrying the American parvenu Dr. Thomas Silkstone, so destroying the English bloodline. So far, he had done rather well. The upstart doctor from the Colonies would surely admit defeat very soon, and as for poor dear Lydia, well, she was so highly suggestible that he could, and had, told her a pack of lies and she would believe anything he said.

Satisfied in such knowledge, he was now able to concentrate fully on his plans to enclose the whole of the Boughton Estate, fencing it off from the commoners and woodsmen. Over a bowl of hot chocolate, he was considering his day’s tasks when Howard entered. From the anxious look on the butler’s normally sanguine features, Sir Montagu could tell he had some urgent news to impart. Howard cleared his throat.

“Begging pardon, sir, but Peter Geech would speak with you.”

Sir Montagu looked up from his bowl, then set it down.

“Geech?” he repeated. He wondered what the landlord of the Three Tuns had to relate that couldn’t wait until later in the day. “Tell him to go away and return at a more civilized hour.”

Howard looked uncomfortable. “He says it is most urgent, sir.” Then, as if to press Geech’s case further, the butler added: “It concerns Dr. Silkstone, sir.”

“Ah!” Sir Montagu paused at the mention of Thomas’s name and suddenly changed his high-handed tune. He dabbed the corners of his mouth with his napkin. “Then you better allow him in,” he instructed.

Peter Geech, always with at least one of his beady eyes on the main chance, was shown into the morning room, clutching the brim of his tricorn. Sir Montagu eyed him like a hawk would a mouse or a vole before it struck, then signaled for Howard to leave.

“Well?” he said, as soon as they were alone. He did not invite the landlord to sit. “You have news concerning Silkstone?”

Geech thrust out his chin, as if he was proud to be the one to break the news. “I thought you’d like to know there’s been a duel on the common, sir,” he began. He paused for dramatic effect.

Sir Montagu paused, too, and arched one of his thick brows. “Tell me more,” he said, leaning back in his chair.

“’Twixt Mr. Lupton and Dr. Silkstone, sir.”

Now both of Sir Montagu’s brows were raised in unison. He leaned forward, his interest piqued. “Has there indeed? And what, pray tell, was the outcome?”

Geech paused again, licking his thin lips, as if relishing what he was about to impart, but his silence spoke to Sir Montagu. He would say no more without a reward. The men’s eyes met.

“A crown,” said the lawyer.

Geech remained steadfast. “I was hoping . . .”

Sir Montagu frowned and leered toward the innkeeper. “I could go to the village and ask any peasant on the street to tell me,” he said coldly. “Then I could have your squalid tavern closed down!” He reached over the table and lifted the china lid of a jam pot, then shut it again to illustrate his point.

The landlord reddened and squeezed the brim of his tricorn. “Of course, sir,” he said, suddenly losing his nerve.

“So?”

“Dr. Silkstone was wounded.”

“Was he indeed?” There was a flicker of a smile on the lawyer’s lips.

“Yes, sir. They brought him to the inn.”

“They?”

“Her ladyship and her maid and the—”

“What? Lady Lydia?” At the mention of Lydia’s name, the scowl returned to Sir Montagu’s face. To the best of his knowledge, she was still sleeping soundly upstairs. He pushed himself away from the table and stood up. “Her ladyship is with him now?” The news clearly angered him. He strode over to the window.

“Yes, sir,” continued Geech. “And now an arrest warrant for Mr. Lupton has been issued by Sir Arthur Warbeck.”

Sir Montagu wheeled ’round, his hands behind his back. “Has it indeed? So the American might die?” He knew that if that were the case, a charge of manslaughter would be brought against the steward. “You have seen him?”

Geech nodded. “Hit in the chest, he was, sir. He’s stone-cold out of it, sir, but Mr. Peabody is seeing to him.”

Sir Montagu allowed himself a chuckle. “Peabody? That clown can kill a man as easily as any lead shot!”

Emboldened by the lawyer’s response, Geech went on: “But I’ve been told to expect Sir Theodisius Pettigrew and another surgeon from Oxford presently, sir.”

The news of the men’s arrival wiped the smirk from Sir Montagu’s face. “The coroner?” He walked forward and grasped the back of his chair. “And Professor Hascher, no doubt,” he mumbled.

“Sir?” Geech did not catch the lawyer’s words.

Sir Montagu reached into his pocket and produced two silver coins. He tossed them on the floor at the landlord’s feet, one after the other. They rolled along the wooden floorboards and came to rest at the edge of a rug. “A crown for the information,” he said, “and another to keep me abreast of the doctor’s condition.” As he watched Geech grovel to pick up the coins, Sir Montagu very much hoped that before the day’s end the innkeeper would be the bearer of news of Thomas Silkstone’s death.

In an upper room at the Three Tuns, three anxious onlookers—Lydia; her maid, Eliza; and Mr. Peabody—were keeping vigil at Thomas’s bedside. There had been a glimmer of hope. The doctor had opened his eyes, smiled at the sight of Lydia, and then been lost to her again. At around midday Boughton’s stable lad, Will Lovelock, had come, bearing a message from Sir Montagu. The lawyer had, said his missive, heard the terrible news and wished Lydia to know that if he could be of any assistance, she had only to say. The carriage was at her disposal, and he had instructed the Reverend Unsworth to say prayers for Dr. Silkstone. His words had offered her a little comfort, although she could not be sure that he meant them. She continued to watch and wait, and as she waited, she, too, prayed, prayed as never before. And she made a vow: Please God, if you let him live, then nothing will stop us being together, I swear.

By the time the clock in the room struck three, there was still no sign of Sir Theodisius and Professor Hascher. Lydia felt her anxiety mount. “Where are they?” she asked aloud, not expecting a reply.

No sooner had she posed the question, however, than Eliza blustered in from a foray to buy fresh herbs to scent the room. She was able to furnish her mistress with an answer.

“They’ve been spotted, m’lady,” she told her breathlessly. “A wheel came off their carriage just north of Woodstock, but ’tis mended now.”

Almost two more anxious hours followed until, just before the church bell struck the hour, a carriage drew into the inn’s courtyard. Inside were Sir Theodisius Pettigrew and Professor Hascher, and their presence had never been more welcome.

“Thank God you are here!” cried Lydia, rushing forward to greet Sir Theodisius as he lumbered into the room. A corpulent gentleman, he enveloped the young woman in a warm embrace. Without children of his own, he had always regarded her as he would his own daughter.

“Dear child,” he told her, “do not fear. Professor Hascher is here.” He glanced at the elderly, snowy-haired man who was advancing straight to Thomas’s side. “He will do everything he can.”

Before the duel, Thomas had sent word of his intentions to the Oxford coroner. Sir Theodisius was fully cognizant of the doctor’s plans, but it had come as a shock to him to learn from Peter Geech on arrival at the Three Tuns what had actually come to pass.

Professor Hascher, a Saxon by birth, set to work immediately while the others retired to a respectful distance. Mumbling to himself in his native tongue, he opened up his medical case and started to examine his patient. While Mr. Peabody was asked to remain to assist, Sir Theodisius thought it best if he took Lydia and her maid outside. He wasted little time in escorting them from the room, leaving the elderly anatomist to probe and suture away from their fretting gaze.

“I think some fresh air may be in order,” the coroner suggested.

Lydia nodded, and together they stepped out into the courtyard of the Three Tuns. Eliza remained in the hall. By now it was early evening and the hostler was watering the carriage horses that had come from Oxford, bringing the coroner and the professor. Sir Theodisius and Lydia slipped unnoticed through a small gate into a shaded garden at the back of the inn. In the last few days, spring had made its presence felt. The grass was ankle-high and studded with drifts of bluebells. An unkempt flower bed teemed with periwinkles and yellow tansies. Lydia knew tansies were often wrapped in funeral winding sheets to ward off insects. She shivered at the thought.

“Here,” said Sir Theodisius. His plump finger pointed to a stone seat that overlooked a stream, and there they sat.

“You mustn’t fret, my dear,” said the coroner, staring at the gurgling water. “The professor will see Thomas right.”

Lydia sighed deeply, her breath trembling in her chest. “Please God let it be so, sir,” she replied. She wanted to cry, but did not. Instead she made a confession.

“I’ve been a fool,” she said suddenly.

Sir Theodisius’s head jolted, sending his jowls wobbling. “What’s this, my dear?”

She pulled the head of an oxeye daisy from its stem and began plucking the petals. “He’s been the only one who’s been true to me.”

The coroner inclined his head. “Ah,” he said, as if suddenly understanding. “Thomas.”

“The thought of losing him . . .” She tossed the daisy head into the stream.

Sir Theodisius nodded and patted her hand. “I know, my dear. I know. Sometimes it takes the prospect of losing someone to make us realize how much they mean to us.”

Lydia looked the coroner in the eye. “He means the world to me.”

The coroner nodded. “Then you must tell him so.”

“I intend to,” she said with a nod, then looked away and muttered quietly, “If I have the chance.”

Just then the latch on the gate clicked, and both of them switched back to see Eliza’s head peering ’round. “Professor Hascher says you may return, m’lady,” she said.

Sir Theodisius smiled at Lydia and squeezed her hand. “Yes, you must tell him so yourself,” he said.

All of them made their way back inside and up the stairs to where Thomas lay. Lydia hurried in first, but stopped short of the bed when Mr. Peabody signaled to her to come no farther. She suddenly saw why. Professor Hascher, his hands still bloodied, was standing back to inspect his handicraft. Appearing to examine the closed wound with an artist’s eye, he nodded to himself. Seemingly satisfied that the stitches were as neat as he could make them, and spaced at equal distances, he took a pair of scissors and snipped the catgut. His shoulders heaved as he allowed himself a deep breath, as if he had not breathed since he began the delicate procedure of tending to his patient’s injury.

Still standing at the foot of the bed, Lydia glanced at the bowl on the bedside table. She was grateful to have been spared the sight of the removal of fragments of shattered metal from the wound, although there was still spilled blood on the white sheets. She was not alone in holding back. Sir Theodisius and Eliza did, too, nervous about what they might see. They were waiting on Professor Hascher’s word, and it came very soon.

“Das ist gut,” he pronounced finally with a nod of his snowy-white head.

With the professor’s announcement, all those in the room seemed to relax a little, as if their nerves had all been held taut by some invisible thread. They had been tense ever since they had known the seriousness of the injury. Now, at last, they could all breathe a little easier.

After another moment’s deliberation, the professor, to everyone’s surprise, addressed his patient. “Zat breastplate may have saved your life, but it still made ze nasty hole in your chest,” he admonished.

Thomas, it seemed, was conscious, and Lydia rushed forward. From the bed, his hand rose, and he placed his fingers lightly along the row of stitches on his chest, as if playing the keys of a fortepiano.

“They feel even enough. You have done a good job, Professor,” came the croaked reply. Although Mr. Peabody had dosed him liberally with laudanum, Thomas had remained conscious throughout the procedure. Through the fog of shock and pain, he had managed to follow the Saxon surgeon’s work cleaning up a chest wound that would, most certainly, have been fatal had he not been wearing protective armor.

“Thank God you are back with us,” exclaimed Lydia as soon as she saw Thomas’s face. He managed to smile at her through his evident discomfort. As the professor reached for bandages from his case, however, Thomas switched his attention.

“A good dollop of aloe balm on the wound would surely not go amiss, sir?” he suggested.

Hascher paused at his words, glanced at Sir Theodisius, then rolled his eyes. The two older men exchanged weary smiles.

“The next time you’re challenged to a duel, Silkstone, I beg you, do not accept, for all our sakes,” exhorted the coroner as he lumbered up to draw alongside the injured young doctor.

Lydia clasped Thomas’s hand in hers. “For mine, especially,” she said.

Thomas, his eyes now fully open but his breath rasping, whispered his reply. “Fear not, sweet lady. ’Tis not grave,” he told her. It was all she had needed to hear. His wound was ugly—she had seen it with her own eyes—but, barring infection, it no longer threatened his life.

“You must rest, now,” Professor Hascher told his patient.

“I think we must all rest,” agreed Sir Theodisius.

As the elderly anatomist set to work binding Thomas’s torso, Sir Theodisius and Lydia, followed by Eliza, beat a retreat from the room.

Peter Geech jumped back as the bedroom door opened and looked sheepishly at Sir Theodisius, who returned a scowl. The landlord had clearly been listening on the landing outside.

“Dr. Silkstone . . . He is . . . ?”

“Alive, Mr. Geech,” came the coroner’s barked reply. The wiry innkeeper nodded his head. “Alive, but with a shattered breastbone and in need of rest,” added Sir Theodisius. “And so am I. I shall have your finest room. And dinner.” He rubbed his large belly, which suddenly felt very empty. “A chop or two will do nicely.”

Geech nodded once more. “I have a room prepared for you, sir, and one for the foreign gentleman,” he replied, casting a look through the door toward Professor Hascher.

“And her ladyship?” Sir Theodisius turned to Lydia.

“Her ladyship’s carriage awaits,” Geech informed him.

Lydia, drawing close, looked relieved. “Then we shall go back to Boughton, sir,” she told the coroner.

Sir Theodisius smiled. “Yes, my dear,” he said, taking her hand to kiss it. “I trust you will sleep better in your own bed.”

She returned his smile and nodded. “I shall sleep better knowing that Dr. Silkstone is out of danger,” she acknowledged.

Lifting up the hem of her skirt slightly, she made her way down the rickety stairs to the hall, where Lovelock was waiting. By now it was growing dark. The taproom was full of men carousing and laughing. The smell of pig fat from cheap candles tainted the air, and it was hard to see through the thick fug of pipe smoke. Nevertheless, the mood appeared much livelier than usual. The ale was flowing, someone had struck up on the pennywhistle, and it seemed to Lydia, as she glanced through the doorway, that the locals had not a care in the world. At the center of the merry throng she caught a glimpse of Joseph Makepeace, the bury man. Normally such a staid and dour fellow, as befitted his calling, he was quaffing his tipple and puffing his pipe as if he were lord of the manor. She wondered perhaps if she should instruct Geech to ask the grave digger and his friends to tone down their revelries so that the doctor would not be disturbed. But as soon as she drew level with Lovelock, shifting agitatedly at the foot of the stairs, the thought flew from her mind.

“My lady, is the . . . ?” the groom began anxiously.

Lydia quickly put him at ease. “Dr. Silkstone is recovering,” she managed to relate, but it was clear she was exhausted and in no mood to tarry. She swept past him. Lovelock’s pock-marked face relaxed, and he caught Eliza’s eye. The maid smiled at him, and together they followed Lydia out into the warm night to the waiting carriage that would take them back to Boughton Hall.

Sir Montagu Malthus would never have called himself a man of faith, but he had been inclined toward prayer throughout the day. As yet, however, his request had met with no divine response. He had received no word from Geech. To his knowledge, Silkstone was still alive. Now his only supplication was that he would not survive the night.

The lawyer sat in the study at Boughton Hall. The evening was warm, and the French windows at the far end of the room were open. The noise of the guard dogs barking in the far distance made him look up and flatten his back against his chair. He was wading through unopened correspondence that had been left to mount over the past few tumultuous weeks. For most of the day his enormous shoulders had been hunched over the desk, and his neck ached. The occasional gulp of claret from a glass at his side had been all there was to break the tedium of the mound of documentation. Now, however, he allowed himself the indulgence of breaking off from reading his papers. It was not the sudden barking that roused him, but the appearance of a moth. Flying dangerously close to the naked flame of his candle, it was quite large and brindle brown. It skimmed and pranced in the enticing circle of light cast on the wall above his desk. Its quivering silhouette made it appear even bigger than it actually was. Fluttering in on the sultry night air through the open windows, the creature provided a welcome diversion. So now he set down his silver paper knife, eased back in his chair, and studied the insect with a macabre fascination.

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...