- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

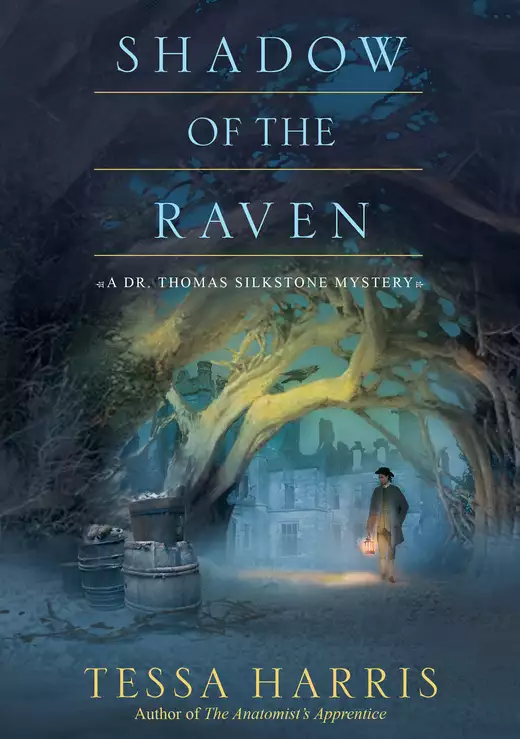

“CSI meets the Age of Reason with a well-drawn, intriguing cast of characters” (Karen Harper) in Tessa Harris’ superbly plotted historical mystery series, featuring eighteenth-century anatomist and pioneering sleuth Dr. Thomas Silkstone.

In the notorious mental hospital known as Bedlam, Dr. Thomas Silkstone seeks out a patient with whom he is on intimate terms. But he is unprepared for the state in which he finds Lady Lydia Farrell. Shocked into action, Thomas vows to help free Lydia by appealing to the custodian of her affairs, Mr. Nicholas Lupton.

But when Silkstone arrives at the Boughton Estate to speak to Lupton, he finds that sweeping changes threaten to leave many villagers destitute. After a man dies in the woods, it appears that someone has turned to murder to avenge their cause. But for Thomas, a postmortem raises more questions than answers, and a second murder warns him of his potentially fatal situation. Soon he discovers a conspiracy far more sinister than anything he has ever faced.

Release date: January 27, 2015

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shadow of the Raven

Tessa Harris

His young assistant’s head darted ’round in shock as his master clipped his shoulder. “S-s-sir!” he stammered.

Cursing under his breath, the older man righted himself, tugging at his fustian coat. As he did so there was a clatter. An object fell from his pocket onto the stony ground below. Having a good idea what it might be, he peered down. And now, as he did so, he noticed that his worsted stockings, although thankfully not torn, were spattered dark red. A closer inspection, however, confirmed the substance was only loamy mud. What concerned him more was the fact that a few inches from his feet he spied the pistol. Mercifully, although fully cocked, it had not fired. Bending low to retrieve it, he secreted the weapon in his pocket once more and allowed a shallow sigh of relief to escape his lips. He felt safer with it about his person. It would be a deterrent, if one were needed, against any undesirables they might encounter. A quick glance up ahead reassured him that his assistant had not seen.

“Infernal stones,” cursed the gentleman out loud, making sure his complaint was heard by Charlton, his chainman. The freckle-faced young man turned ’round and nodded his red head in agreement.

Jeffrey Turgoose, master surveyor and cartographer, a man held in high regard by the rest of his profession, should have worn stout boots more suited to a woodland trail, although, admittedly, he had not anticipated having to make his way through the forest on foot. A series of unfortunate events had, however, necessitated it.

First and foremost, his employment, thus far spent in the service of Sir Montagu Malthus, the new caretaker of the Boughton Estate and lawyer and guardian to the late sixth Earl Crick, had been fraught with difficulties. Every time he had set up his theodolite in the estate village of Brandwick, he had been taunted by barefoot urchins or impudent fellows intent on disrupting his mission. There had been threats, too. In his pocket he carried the note that had been slipped under his door the other night. Beware of Raven’s Wood, it warned him. Heaven forbid that Charlton should see that! The boy would run all the way back to Oxford. Turgoose harrumphed at the very thought of it. No, it would take more than ignorant peasants and a badly scrawled warning from a lower sort to deter him. Nonetheless, such unpleasantness did, of course, rankle. He could not pretend otherwise, and it added to a certain miasma that seemed to hang low over Brandwick and its surrounds.

From what he had gleaned, there seemed to have been great ructions on the estate. Apparently, the death of Lord Edward Crick, swiftly followed by that of his brother-in-law, Captain Michael Farrell, had been most inopportune. They meant that the latter’s widow, Lady Lydia Farrell, had inherited Boughton. It was thought she was childless, but the reemergence of her long-lost young son and heir, thanks in no small part to an American anatomist by the name of Dr. Thomas Silkstone, had put a fly in the proverbial ointment. What’s more, it appeared that such upheavals had taken their toll on the poor woman and sent her quite insane. She was now safely ensconced in a madhouse, and Sir Montagu had installed a steward to take charge of the quotidian running of the estate.

If that were not enough, Jeffrey Turgoose was encountering his own problems. First the cart that carried himself and his equipment became bogged down and stuck fast in the yielding ground leading up to the wood. For the past few months now man and beast had left their imprint on the sodden earth. Now the cartway was so beaten down by wheels and hooves it had become impassable. Not wishing to abandon his plans, the surveyor had continued with just one blasted mount that went by the name of a horse, although in reality it was just as stubborn as a mule. His assistant, Mr. James Charlton, had been forced to dismount and walk in order to lay the burden of all the paraphernalia of their profession on his own horse. Peeping out of one pannier were bundles of markers and a circumferentor, while the other was packed with measuring chains. A tripod was strapped to the saddle, along with some measuring poles, making the poor horse appear as if she had been run through with a picador’s lances.

Such unforeseen irritations had put the surveyor in a very sour humor. Was his mission not onerous enough? He was not accustomed to exercising his profession under threat from local ruffians, but such had been the villagers’ reaction to their presence, he had been compelled to take precautionary measures. The ignorant peasants were harboring the notion that the common land had been bestowed upon them by some mythical woman. “The Lady of Brandwick” they called her, and they all knew the legend. While still at the breast they were taught how, in the days before Bastard William invaded, a lady had ridden a circuit of the area from the edge of the woods to where the oxen could ford the river. In her hand she held a flaming brand and by her favor she gave the land to the villagers. That was how the parish came to be known as Brandwick, and that was how they came by their ancient rights. Or so they thought.

In fact, Boughton’s steward, the Right Honorable Nicholas Lupton, appointed by Sir Montagu as the new custodian of the estate, had indicated that he felt his own position was being compromised by such innate insubordination. The Chiltern charcoal burners, turners, and pit sawyers who labored in the forest all day were not known to be militant men, Lupton had told him, but since their livelihoods were under threat, since their cherished rights were in peril, there was no telling what they might do. Pointing out that there had been riots in other parts of the country where landowners had endeavored to enact similar measures, the steward had persuaded Turgoose to have a greater care for his own safety and that of his assistant. He had been persuaded by Lupton’s recommendation of a guard and guide, Seth Talland, an occasional prizefighter and an uncouth sort. The man seemed competent enough, and, as it turned out, he was most thankful for his presence. Apart from the threat of lurking highwaymen and footpads, there were gin traps, too, set about the woodland floor to deter poachers. There were still a few men in Brandwick who’d suffered a leg snapped in two by the iron jaws of such a brutal device. They never poached, or walked without a limp, again.

Lupton had told him there were upward of three hundred acres of woodland, and measuring the boundaries alone would take three days at a conservative estimate. He’d heard that in America they’d surveyed seventeen thousand acres in just over a sennight in Virginia. But they had not measured angles to the nearest degree, and their distances were to the nearest pole. Such slipshod work would not pass muster with Jeffrey Turgoose.

“W-would you r-rest, s-sir?” Charlton’s speech was always labored, and often the most frequently used words seemed to cause him anguish, yet he looked even more concerned than usual.

“A moment,” Turgoose replied, turning his back to the slope and looking down into the valley at Brandwick. A fading sun hung in a patchy sky, offering a less-than-perfect light. He was glad of his decision to bring his trusty old circumferentor instead of his usual theodolite. Akin to a large compass, it worked on the principle of measuring bearings. It would be particularly advantageous, he felt, in such a heavily forested area, where a direct line of sight could not be maintained between two survey stations, even though he could see the tower of St. Swithin’s Church clearly enough. He shook his head as he took in the view. He’d even heard of some of his colleagues having to survey land under cover of darkness, like fly-by-night poachers, such was the strength of feeling against enclosure.

Of course, Turgoose, too, had expected some suspicion and resentment. He was accustomed to that from those who had most to fear from enclosure, cottagers, mainly, and those who faced losing their livelihoods. A free rabbit for the pot or kindling for the fire had been the mainstay of many a paltry existence over the centuries. But times were changing. Land was a precious commodity, best managed by those who knew how to make it pay. So he and his assistant had been commissioned to plant themselves on Brandwick Common like unwelcome thistles, to record the mills and monuments, the wetlands and ponds, and the bridleways and tracks and paths made by feet that had trodden them freely since time immemorial.

To those ignorant peasants, he and his assistant may as well have been alchemists, with their strange equipment in tow. There was, of course, an analogy. Alchemists turned metal into gold, while he and his cohort were turning land into potential profit. That is what his client, Sir Montagu, wanted to do on behalf of Lord Richard Crick, Boughton’s six-year-old master.

Despite the hostility from the villagers, the surveyors had managed to do a good job thus far. The weather, although on the chilly side, had been fair, the sky clear, and their observations and measurements easily recorded. After the common land, they had turned their attention to the village dwellings, the market cross, and the church, all lying within the boundaries of the Boughton Estate. Precision and order could be imposed on this chaotic fretwork of man’s own making using that most noble of shapes, the triangle. Trigonometry was the answer to all humankind’s conundrums; at least that is what Jeffrey Turgoose had told Charlton and anyone else who would listen. After all, was it not Euclid, the father of geometry, who said that the laws of nature were but the mathematical thoughts of God? To that end, he had convinced himself that he was doing the Almighty’s work, and this confounded wood was his final task.

Up ahead, Talland, his scalp as bald as a bone, looked ’round to see what had happened to his charges. Set square as a thicknecked dog, he carried a club for protection, and a small sickle hung from his waist.

“All well, sirs?” he called back in a coarse whisper. Thankfully he was a man of few words, thought the surveyor.

“Well enough,” replied Turgoose. He gave Charlton a knowing look and proceeded to delve into his frock coat pocket. He checked that the pistol was still there. The youth did not suspect. Such knowledge would send him into paroxysms of fear. Instead Turgoose brought out a hip flask and took a swig.

Talland emerged from the lengthening shadows a moment later.

“I’ll make safe our way, sirs,” he told them. “I ’eard sounds from up yonder.”

Turgoose nodded, then turned his back and gave a derisory snort. “I’ll wager you have heard sounds, man,” he said to himself as much as to Charlton. “We are on the edge of a wood. There are foxes, squirrels, and all manner of creatures, not to mention the wretched charcoal burners and sawyers.” He shrugged, took another swig, then plugged the flask once more.

The old mare shifted as she stood and began to fidget under the weight of her burden. Charlton frowned at his master.

“Wh-what if there’s s-someone up there, s-sir?” he asked. Turgoose noted that when his assistant was anxious, the register of his voice went even higher than usual. Dropping the flask into his pocket, the surveyor shook his head.

“Then Talland will deal with them,” he reassured the chainman, even though he did not feel entirely secure himself. This was no way to carry on: three men, and a mare that should’ve been boiled down for glue a long time ago. His was a most burdensome and precise task, so why had he been made to feel like a cutpurse or a scoundrel going about his business?

As they breasted a small ridge, Talland, who had momentarily been lost from sight behind a screen of spiky gorse, came into view once more. The prizefighter had made it to the trees and was entering the wood through an avenue of tight-packed hawthorns. If need be, he would clear a path for them to follow a few paces behind.

The beeches were still naked after one of the longest winters in memory. Crows’ nests clotted their bare branches and russet leaves still patterned the woodland carpet. Crunching over cast-off acorn caps and husks of beech mast, the small party proceeded at a tolerable rate. They wove through green-slimed trunks and past thickets as tangled as an old man’s beard. By now they had left behind the birdsong and the caw of the crows, although the odd pheasant would let loose a throaty call. All the while they were heading deeper and deeper into the woods.

Turgoose’s plan was to determine the apex of the hill in the wood and then take measurements using the church tower as a fixed point. The task would have presented its own challenges had he been operating in clear conditions, but with the fading light the execution of such an undertaking would rightly be considered sheer folly by many of his fellow surveyors.

Moments later the party found themselves progressing along the narrow avenue of hawthorns. Underfoot it remained muddy, but Talland had found a serviceable path that, judging by the lack of vegetation, seemed to be in regular use. They were forced to travel in single file, with Charlton leading the horse first. They had journeyed perhaps a mile into the woods when the mare’s ears pricked and she came to a sudden halt. The young man tugged at her leading rein.

“Come on, old girl,” he said firmly. Instead of obeying the command, however, she began to backstep, forcing Turgoose to retreat.

“What goes on?” he called from the rear.

“She’s afraid, sir. . . . S-something tr-troubles her.”

Turgoose tutted and, seeing a row of dried-out stalks at his side, he broke one off near its root and thwacked the mare’s hindquarters.

“Get on with you,” he cried.

The shock had the desired effect and the horse moved at once. It was Charlton who was now reluctant to budge.

“Well, man?” asked Turgoose impatiently. “What is it now?” Passing the horse, he drew up alongside his nervous assistant to find him squinting into the distance.

“ ’Tis T-Talland, s-sir. I’ve lost s-sight of him.”

Turgoose strained his eyes in the woodland gloom.

“Talland,” he called. “Talland.”

They waited in silence for a reply. None came. Charlton’s expression grew even more fearful. He started to say something. His mouth opened and he tried to form a word. His tongue jutted out and he grunted, but his master cut him off.

“We’d best catch up,” said Turgoose in his no-nonsense fashion. He did not want to betray his own unease at the prospect of losing their guard. If they were waylaid by an unruly mob here, they would have little chance of assistance from any quarter. He barged forward, past Charlton, intent on finding Talland, only as he did so he heard something crunch beneath the thin sole of his shoe. It was definitely not a twig. He glanced down. The carcass of a dead raven, or rather part of a carcass, lay under his foot. Its head was the only recognizable feature that remained intact. The rest of its body, save for a few feathers, was nowhere to be seen. The surveyor’s nostrils flared in disgust as he scraped the sole of his shoe on nearby leaves.

“What time is it?” he barked, looking up to see the young man’s anxious face.

Retrieving his watch on a chain from his pocket, Charlton flipped open the cover.

“Almost f-five of the clock, sir.”

“We must press on.” There was an urgency in the surveyor’s voice. “Talland! Talland!” he called.

They quickened their pace in the direction where they had last seen their guide. Without him they were lost. They were too far into the woods now to retrace their steps. The old mare was happy to oblige at first and hurried her pace, too, but then slowed again, becoming agitated after only a few yards. The trees were pressing in around them, their branches twisted into grotesque shapes against the sulfur yellow of a dusky sky. A mist was rising from the woodland floor, making it harder to find their footing as the gradient began to climb again.

“Talland. Talland,” Turgoose called. Still no reply, but a noise.

“Wh-what . . . ?”

They stopped in their tracks to listen. They heard footsteps heading toward them through the undergrowth. Talland reappeared.

“All clear up ahead, sir,” the guard shouted to Turgoose.

Charlton edged forward, tugging at the mare’s leading rein, but she refused to budge. Seeing that the young surveyor was having difficulty with the horse, Talland offered to lead her.

“Let me, sir,” he said, walking over to the mare and taking her by the rein. He began to walk on ahead once more.

Despite the fact that Talland had endeavored to clear it, the path grew narrower and the trees’ gnarled fingers still reached across it. To make matters worse, the mist was thickening and made visibility poor. In his mind Turgoose determined that they should abandon this foray altogether. He would inform Talland of his decision. Before he could do so, however, he felt the whip of a twig lash his cheek, and the stinging sensation momentarily robbed him of his breath. He gasped and let out a sharp cry.

“S-sir!” came Charlton’s plaintive voice from behind him.

“A scratch! Nothing to worry about.” Turgoose rubbed his cheek and felt the syrup of warm blood on his fingers. Talland, a few paces up ahead with the horse, did not even bother to look ’round. They set off once more. They had gone only another few paces, however, when, from somewhere nearby—it was hard to tell where—there came a shuffling and the sound of cracking twigs.

“S-sir, d-did . . . ?”

“Yes, I heard it, Charlton,” snapped Turgoose. Suddenly he found himself feeling very slightly afraid. Perhaps they were being watched by the villagers, mocked silently as they braved the woods. Or worse still, a highwayman. He would give the villain anything he wanted: his pocket compass, his silver flask, even all his equipment. But he digressed. He gathered his courage and tried to dismiss his fears. He looked up ahead. The horse’s rump appeared now and again through the trees, but Talland seemed to be powering on regardless of his charges’ much slower pace.

“S-sir. We must g-go back,” Charlton whined again.

“You’re probably right,” conceded Turgoose. “We shall try again tomorrow.”

“Y-yes, s-sir,” answered the youth, his shoulders heaving in a sigh of relief.

No sooner had Turgoose decided to call to Talland, however, than up ahead he heard the horse let out a loud whinny.

“What the . . . ? Talland?” the surveyor called. There was no reply.

Charlton stayed rooted to the spot, his legs planted by fear. His body, however, began to shake violently. Turgoose shot the sniveling wreck of a youth an irritated look. He may have been his master, but he was not a soothsayer. How was he to know what had happened to Talland up ahead, any more than the chainman? Naturally the surveyor feared he had been ambushed, waylaid by the mob, but he must not show his own trepidation to Charlton. He appeared circumspect.

“Wait here,” he said.

“S-sir?” His assistant looked at him with baleful eyes, as if pleading not to be left alone. His master, however, was adamant. Charlton was more of a hindrance than a help. Nevertheless, as he started to walk toward where he had last seen Talland, he remembered the pistol. He patted his pocket. It was still there. He turned.

“If it makes you feel any safer, take this,” he said, plunging his hand into his coat and placing the firearm in the youth’s palm. He closed Charlton’s fingers ’round the walnut grip.

The chainman’s eyes bulged as if he had just been handed a poisoned chalice or dubbed with a mariner’s black spot.

“You’ll not need to discharge it, I’m sure,” his master reassured him, “but if you are threatened, just point it at anyone who challenges you. They will take fright and run.”

Charlton, looking down at his hand, his mouth wide open, swallowed hard.

“Y-yes, sir,” he said.

Satisfied he had gone some way to relieving his assistant’s anxiety, Turgoose turned and resumed his quest to find the guard. “Talland!” he called.

Within seconds Turgoose had disappeared from Charlton’s sight and had located the prizefighter a few yards ahead. He was struggling with the mare. The old horse had stumbled into what seemed like a deep ditch and appeared unable to extricate herself. Talland was tugging at her rein, trying to coax her out, but she was reluctant to oblige.

“A sawpit, sir,” he explained, pulling at the horse. “Woods are full of ’em.”

Although he appreciated the difficulty that the situation presented, Turgoose found himself smiling. It was a minor inconvenience compared with the ambush he had envisaged.

“I must fetch Charlton. He will help you,” he told the guide. He turned back to retrace his steps. How relieved his chainman would be, he told himself, rustling back through the bushes once more. He could see him now, still visibly shaking, his back to him, but only a few feet away. His gangling body was framed by thick foliage. The surveyor opened his mouth to call to him, but before he could make a sound, the youth twisted ’round violently, his eyes wide in terror. Suddenly a high note split the air, a semiquaver of a shout, a warning perhaps. It was followed a heartbeat later by a shot, a single report that sent a murder of crows scattering above the trees. There was an odd gurgling sound, as if a new spring had bubbled its way above ground, a rustling of leaves, and a dull thud as Jeffrey Turgoose hit the strew of the woodland floor. Then silence. This time the dark stains that spattered his worsted stockings were not just mud. They were most definitely blood.

Had he not known what horrors lay within its walls, Dr. Thomas Silkstone would have surmised this magnificent building was a bishop’s palace or the Lord Mayor of London’s residence. The fine, towering façade of Bethlem Hospital was surrounded by pleasant avenues of trees and shrubs that afforded a place of recreation for those of its patients well enough to enjoy them. Yet, despite its pleasing aspect, the edifice before which he now stood held only trepidation for him. Somewhere inside those thick walls with their grand pediments and colonnades, Lady Lydia Farrell was held captive. Taken against her will and certified insane by a corrupt physician on the orders of her late brother’s guardian, Sir Montagu Malthus, she was a prisoner. Thomas had not set eyes on her for almost two months. Despite repeated requests and letters to the hospital’s principal physician, Angus Cameron, his efforts had drawn a blank.

Once more Thomas found himself proceeding toward the grandiose entrance. He had lost count of the number of visits he had made. Glancing up he saw the familiar elaborate carvings depicting melancholy and raving madness on either side of the door. At this point he always found himself seized by the same sense of deep unease that he had experienced when poised on the threshold of Newgate Jail. This institution may have called itself a hospital, but care and compassion were seldom prescribed.

Proceeding through a grand central door and down a hall that opened out onto a great central staircase at its end, Thomas was directed into a reception office. There, behind a high desk, sat an officious clerk with bulging eyes. Thomas noted that they were probably a symptom of goiter, but the man’s brusque manner did nothing to solicit empathy. Thomas had encountered him on several previous occasions, but the man had never endeared himself to him. Yet again the doctor felt himself tense. His efforts to see Lydia had never taken him beyond this point. He had always been refused admission. Judging by the clerk’s familiar expression of contempt, today would be no different.

“Yes?”

“I am come to see Lady Lydia Farrell,” Thomas heard himself say for the umpteenth time, knowing the fellow was fully aware of his intentions. His voice sounded thin and hollow, as if it belonged to someone else, and the words scratched in his mouth.

With the supercilious air bestowed on him by his modicum of authority, the clerk looked down a list in a ledger before him. He cleared his throat but said finally, “I regret, sir, her ladyship remains indisposed.”

These regular encounters had degenerated into a type of pantomime farce, with each man having his set lines and gestures. After the first shake of the head, Thomas would move forward and repeat his request. The clerk would lean backward, blink—slowly because of the size of his eyes—and look vaguely indignant; then the doctor would sigh heavily and retreat, admitting defeat once more. Only on this occasion it was different. On this particular morning the clerk conveyed a further message to Thomas. “Her ladyship is indisposed, and furthermore I am to tell you, Dr. Silkstone, that you will no longer be allowed within the hospital grounds until further notice.” His words were haughty and deliberate. He was clearly a willing messenger.

Thomas dipped his brows. Unprepared for such a rebuke, he felt his normal self-control tested to its limits. “I demand to see Dr. Cameron!” he said firmly. “Fetch him, if you please.” He slapped the desk. The clerk’s bulging eyes registered an affront, but he withdrew, leaving the doctor to pace the room. Suddenly, from a low door at the side, two men in hospital livery marched in. Approaching the doctor, but without warning, they grabbed him by both arms.

“What is the meaning of this?” Thomas asked indignantly.

The clerk reappeared, his eyes seeming to protrude even further from their sockets. “Orders, Dr. Silkstone,” he said, barely able to hide his satisfaction. “You must be escorted from the premises.”

Dr. William Carruthers had never known his protégé so dispirited. Despite the fact that he could not see the frustration on Thomas’s face, the scowl on his lips, or the furrow on his brow, the old anatomist could hear the drawers being rifled and the cupboard doors being slammed in wrath.

“You were refused entry again?”

He knew there could be no other reason for Thomas to exhibit such uncustomary ire. He had tapped his way to the laboratory with his stick to investigate the noise and found the young doctor gathering his equipment with undue haste. Thomas paused as he packed his medical case.

“Worse, sir,” he replied, pausing to look up. “This time I was thrown out of the hospital like a common criminal.” His voice trembled slightly as he spoke, not with weakness but with rage.

Carruthers shook his head sympathetically. “So what will you do now, dear boy?”

Not usually one to abandon any goal, Thomas took a deep breath. “It is useless trying to gain access to Lydia by conventional means,” he said enigmatically. He reached for a reference book from the shelf, sending dust motes dancing about the room, and dropped it into the case.

“Ah!” Dr. Carruthers raised a finger, certain that his protégé had formulated another plan. “So you will approach the conundrum by an unconventional route. What other means do you propose?”

Thomas shrugged his shoulders and continued packing his case. There was nothing scientific in his methods of dealing with Lupton or Sir Montagu Malthus. He only wished there could have been. Had they been tumors, he would have cut them out long ago and been rid of them both. As it was, there seemed no logical way of dealing with these Machiavellian charlatans who had so blighted his beloved Lydia’s life and, therefore, his own.

“I shall simply go to Boughton and see if I can persuade Nicholas Lupton of the error of his ways before I confront Sir Montagu,” he told his mentor, securing the stopper on a bottle of iodine.

“So you believe Lupton is Malthus’s weak spot, as it were?”

Thomas detected a note of skepticism in the old anatomist’s voice. He nodded to himself and paused in thought for a moment. “I do. I refuse to believe that there is not a shred of humanity within him. He befriended her ladyship and her son, and the young earl’s affection for him was clear to see. Call me naïve, but that surely counts for something.”

Dr. Carruthers nodded. “It is good to know that even after all the betrayal you’ve suffered, you can still see goodness in everyone.”

Thomas looked up suddenly, sl. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...