- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

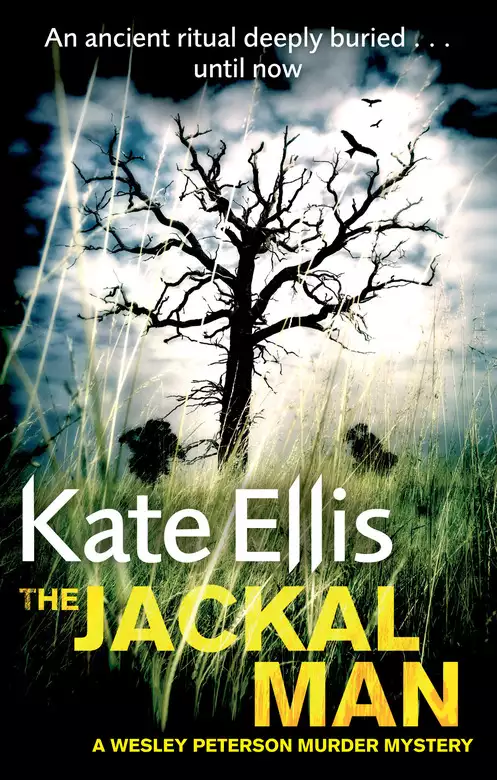

Synopsis

When a teenage girl is strangled and left for dead by an attacker she describes has having the head of a dog, the police are baffled. But when the body of another young woman is found mutilated and wrapped in a white linen sheet, DI Wesley Peterson suspects that the killer is performing an ancient ritual linked to Anubis, the jackal-headed Egyptian god of death and mummification. Meanwhile, archaeologist Neil Watson has been called to Varley Castle to catalogue the collection of Edwardian amateur Egyptologist, Sir Frederick Varley. However, as his research progresses, Neil discovers that Wesley’s strange murder case bears sinister similarities to four murders that took place near Varley Castle in 1903.

Release date: February 3, 2011

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 398

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Jackal Man

Kate Ellis

As she hurried down the lane, the high hedgerows looked naked and dead in the silvery darkness. The wind was gusting harder

now and the cold seeped through her thin coat like icy fingers touching her flesh.

She broke into a run, grateful that at least she’d had the foresight to put on her flat boots. In high heels, this walk would

have been impossible and maybe she’d always suspected that Jen was going to let her down. Jen’s promise that she’d be there

to provide a lift home from the Anglers’ Arms had seemed half hearted but Clare had convinced herself – and her mother – that

all would be fine. Besides, there’d always been the option of calling a minicab if the plan fell apart. Until she’d looked

in her purse at five to eleven and realised that the last of her money had gone on a fourth Bacardi and Coke.

The other girls lived in the opposite direction and had already arranged their own transport so there’d been no room in their

minicab. As they’d left, Vicky had given her a pitying look and told her that she’d be fine walking home: it was only half

a mile away, across the main road into Tradmouth and then down a narrow country lane flanked by farmers’ fields, so what was

she worrying about? Vicky had always been a bitch. She’d always managed to make Clare feel dim and clumsy but she was clever

enough never to cross that narrow and precarious boundary into bullying.

A tree ahead creaked in the wind and its bare arms waved to and fro as if warning of danger ahead. Clare walked on, avoiding

the puddles that glistened like mercury pools in the light of the full moon. She could smell manure and damp vegetation as

the moon suddenly disappeared behind a bank of clouds. Then, in the shock of the darkness, she stumbled over something lying

in the lane. She put out a tentative hand to see what the obstacle was, hoping that her fingers wouldn’t meet the soft dead

corpse of some creature run down by a speeding car. But when she felt the rough, cold wood of a fallen branch she exhaled

with relief.

As she levered herself up an owl swooped out of nowhere and the sudden movement of those silent, ghostly wings sent a shock

through her body. But she forced herself to stand and ignore the stinging graze on her knee and the gaping hole in her new

patterned tights. Just a couple of hundred yards to go now. Then she’d be in sight of home.

Suddenly a throaty noise shattered the darkness like the roar of a lion. She froze and pressed her body against the hedgerow,

wincing as the twisted wood bit into her flesh. After a couple of seconds a pair of bright headlights lit up the lane. Temporarily dazzled, Clare shielded her eyes as the vehicle shot past. And as the sound of the engine receded,

she stood quite still by the side of the road until her eyes readjusted to the moonlight.

She took a deep breath and began to walk on, trying to ignore the sounds of the night; the eerie scream of a distant fox,

the predatory screech of an owl. She was nearly home.

But the animal she saw as she rounded a blind bend made no sound as it walked silently towards her. A strange creature the

size of a man, stalking on cloven hoofs like the devil.

It didn’t move particularly fast but she sensed its power. If she attempted to get away she knew it could follow and outrun

her easily. But she had to make the effort to escape somehow, even though her limbs felt heavy and useless, as if some unseen

force had fixed lead weights to her feet.

In the middle of the Devon countryside there was nobody to hear you scream and Clare knew that, even if fear hadn’t paralysed

her throat, any cry for help would be futile.

With a huge effort she turned away from the thing and attempted to run. There was a cottage back near the main road and if

she could just reach it she would be safe. So with the vision of that glowing cottage fixed in her mind like some heavenly

city, she began to move. There was no need to look back to see whether it was still following: even though it moved silently

she knew it was behind her … and getting closer.

As it caught her waist she lost her footing and stumbled to the ground, unaware of the pain as the gravel bit into her knees.

Then the thing’s soft hands, like great paws, closed around her neck and something thin that felt like wire began to bite

into her flesh. Her hands shot up instinctively to her throat and she tried with all her strength to wrest the thing off. But the thin ligature cut in deeper as she fought for each precious breath.

Clare’s struggle for life seemed to last forever. But in reality it was only a few seconds before she was vaguely aware of

the droning engine of another vehicle, approaching with frustrating slowness. All of a sudden she felt herself tumbling forward

again onto the rough road surface as her body was released from the creature’s murderous embrace, and she lay there stiff

with terror, hardly daring to move. Whatever it was had let her go but it could still be there waiting in the shadows like

a cat preparing to return to a bird half tortured to death for its pleasure.

Then headlights appeared around the bend, bathing Clare’s body with light as she lay sprawled across the road. But by the

time the van had screeched to a halt, she had lost her fight for consciousness. And the thing that had tried to take her life

had disappeared off into the night.

February is the quietest month. The festivities of Christ mas are a vague and rosy memory and spring, when tourists descend

on South Devon like migrating birds, seems a long way off.

So when the phone by DCI Gerry Heffernan’s bed began to ring at half past midnight on Monday morning, he was unprepared for

the interruption to his deep, complacent sleep. He wrestled with the duvet that had wrapped itself around his plump body and

at first the duvet won the fight. But as his brain began to function he managed to escape its clutches and flick on the bedside

light.

He picked up the receiver and put it to his ear, rubbing his eyes and wondering if he had any clean shirts ironed. This was

bound to be something that required him to get up and dressed and venture out into the cold night air. A phone call at that hour always heralds bad news. This was somebody’s tragedy.

Once the officer on the other end of the line had conveyed all the details, Gerry asked the inevitable question, dreading

the answer.

‘Is the lass expected to live?’

There was a long silence. ‘We don’t know yet, sir. But if the motorist hadn’t found her when he did …’

‘What do they say at the hospital?’

‘You know what doctors are like, sir.’

Gerry understood. He knew what doctors were like all right. Like lawyers they tended not to commit themselves to certainties.

‘Inspector Peterson’s already on his way to the scene, sir. Do you want me to organise a patrol car to pick you up?’

Gerry answered in the affirmative and fifteen minutes later, wearing yesterday’s crumpled shirt, he stumbled out of the house

and onto the quayside. A thin veil of mist had come down over the river but he could still make out the streetlights of Queenswear

on the opposite bank. As he walked to the patrol car, hands in pockets and the scent of seaweed in his nostrils, he looked

around, drinking in the night sounds magnified by the water and the night air; the gentle lapping of the river against the

quayside and the distant metallic clink of halyards against the masts of yachts bobbing on the tide. There was no traffic

on the river at this time of night – the fishing boats had departed hours ago and wouldn’t return till dawn – and all the

town lay in silent misty darkness. He sat in the passenger seat and looked out of the window as he was driven away from the

town up the steep hill past the Naval College and out into the open country side.

The car turned sharp left by the darkened bulk of the Anglers’ Arms and Gerry noticed a patrol car pulled up onto the grass

verge outside a cottage on the corner opposite the pub. But Gerry’s car drove on past. The crime scene, the constable explained,

was further down the lane.

As they rounded a bend Gerry saw another patrol car blocking the single-track road ahead. His car screeched to a halt behind

it and he climbed out of the passenger seat slowly, yawning widely like some large, sleepy animal. Being half asleep when

he left the house he had thrown on the first coat that came to hand, not his warmest, and now he shivered in the damp night

air.

The road ahead was lit by dazzling arc lights and a trio of men in white crime-scene suits were conducting a painstaking

search of the lane and the hedgerows either side. He looked about for a familiar face and he spotted a tall, dark-skinned

man in his mid-thirties, leaning on the bonnet of the patrol car, arms folded, watching the proceedings with detached interest.

DI Wesley Peterson was wearing a weatherproof coat, the kind worn by the hardier type of yachting enthusiast, and warm gloves.

Unlike his boss, he had come prepared.

When Wesley saw Gerry his face lit up with what looked like a smile of relief.

‘So what’s the story here, Wes?’

‘A motorist found a girl lying in the middle of the road. He almost ran over her but he managed to stop his van just in time.

He called the ambulance then he got out and went to see if he could do anything.’ He paused. ‘He assumed she’d been the victim

of a hit and run but …’

Gerry knew there was more to come. If it had been a simple hit and run he and Wesley wouldn’t be there freezing their balls off at one fifteen on a chilly Monday morning. ‘But what?’

‘The bloke who found her works at Tradmouth Leisure Centre and he’d been on a first aid course so he tried to roll her over

into the recovery position. Then he noticed her neck: she’d been strangled with something thin like a cord or twine which

had bitten quite deeply into her flesh, but she was still alive. They’ve taken her to Tradmouth Hospital.’

‘Where’s the driver who found her?’

Wesley turned and pointed to a small white van pulled up on a section of wide verge a few yards behind them next to a farm

gate. Gerry must have passed it on his way there but hadn’t noticed with all the activity ahead of him on the road. There

were two shadowy figures inside the van and the windows had begun to steam up.

‘Let’s go and have a word, shall we? What’s his name?’

‘Danny Coyle – he lives in a rented cottage in Whitely with his girlfriend and he was on his way back from having a drink

with some mates in Tradmouth. He seems a bit shaken up. Paul’s in the van with him taking his statement.’

‘Bet your Pam wasn’t pleased at having her beauty sleep disturbed,’ Gerry said as they made their way slowly back down the

lane to where the van was parked.

‘You could say that,’ Wesley replied quietly in a tone that told Gerry that further enquiries wouldn’t be welcome.

When they came to the car Gerry rapped sharply on the steamed-up driver’s window. The passenger door opened and as the interior

light came on he saw a muscular, shaven-headed young man wearing a tracksuit in the driver’s seat. Sitting hunched beside

him with a clipboard on his knee was DC Paul Johnson. Paul was in the habit of running marathons and the driver had a decidedly sporty look so Gerry guessed the pair would have a lot in common.

The driver opened the door and sprang out eagerly, as though he was glad of a chance to get out into the air. Paul did likewise,

uncurling his tall frame from the cramped confines of the seat and stretching out his long legs.

‘Mr Coyle? I believe you found the young woman, sir,’ Gerry began after introducing himself.

‘Yeah. I’ve just given a statement. Can I go now?’

‘Yes, no problem. But before you go, can you just go over what you saw?’

Danny Coyle nodded meekly. Too much exercise had deprived him of a discernable neck and the arms that bulged beneath the thin

cloth of the tracksuit top looked powerful. Certainly powerful enough to strangle a woman.

‘I’ve told him all I know,’ he said, nodding towards Paul. ‘I was just driving home when I saw a girl lying in the middle

of the road. I presumed she’d been run over – hit and run – so I got on my mobile and phoned for an ambulance then I got out

to see if I could do anything.’

‘Did you see or hear any other vehicles? Please think carefully.’

Danny shook his head. Then he thought for a moment. ‘Come to think of it, I might have heard a car engine in the distance

just as I got out of the van. But it might have come from the main road. I don’t know. I rolled her over into the recovery

position and felt for a pulse. But when I touched her neck I realised it was all … well, all sort of cut. I’d kept my

headlights on and when I looked more closely I could see that there was a sort of bloody line around her neck. I could feel

a pulse so I knew it wasn’t too late. I just wanted the ambulance to come before … Anyway, I thought I’d better ring you lot as well. I mean that mark on her neck looked … Have you heard how she is? Did she make it?’

Gerry and Wesley exchanged looks. That was the next thing they had to find out.

There had been several occasions during Dr Neil Watson’s life when he had felt out of his depth and this was one of them.

He wasn’t really sure why he, of all people, had been contacted. But there were many, he supposed, who, on hearing the word

‘archaeologist’, thought automatically of Howard Carter and Tutankhamen’s tomb or Schlie mann’s magnificent treasures of Troy.

If only they knew that life in the Devon County Archaeological Unit was mostly mud and paperwork.

But Neil didn’t feel inclined to enlighten anybody just yet. For one thing he’d always wanted to see Varley Castle. The concept

of somebody building a forbidding granite fortress on the edge of Dartmoor during the late nineteenth century when there was

little need to defend yourself against marauding neighbours intrigued him. He had seen photographs of the castle perched on

a gorge above a glistening river, but photographs can never really capture the feel of a place or give anything more than

a hint of its breathtaking magnificence.

Once he’d left the main A30 from Exeter, the castle hadn’t been particularly easy to find, tucked away down a single-track

lane as if its builder had designed it as his own secret kingdom. He’d driven between a pair of massive granite gateposts

that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a prehistoric stone circle, then up a meandering driveway flanked by fields and

mature woodland. Finally the castle came into view. The moment of revelation had probably been planned carefully by the owner and architect to impress the approach ing visitor

and this theatrical sleight of hand – like a magician whipping off a velvet cloth to reveal some wonder beneath – had worked

to perfection. Neil brought the car to a halt and sat there for a few moments, taking it all in.

To the casual observer it looked as though Varley Castle had been hewn from some great granite cliff. Only the tall windows

betrayed the fact that it had been created by man rather than nature. It looked like something from another, more warlike

age with its crenellations and its great square towers as it stood, dark grey against the soft green landscape. It was a statement

of power but its creator had been no medieval warlord. This great building, Neil knew, was an expression of financial rather

than military might.

As the watery winter sun emerged from behind the clouds, he put the car into gear and carried on. He had an appointment with

Caroline Varley at ten o’clock and he didn’t particularly want to be late – even though he feared that he was bound to be

a great disappointment to her.

Leaving his old yellow Mini on the gravel circle in front of the castle’s great oak door didn’t seem appropriate somehow,

like leaving a piece of chewing gum stuck to some great Rodin sculpture. But, lacking an obvious alternative, he drove carefully

to the edge of the gravel, as far as possible from the door, and stopped the engine.

He’d brought the battered briefcase he used when he had meetings to attend. But when he took it off the back seat he realised

how shabby and scuffed it was. This wasn’t something that usually concerned him – he was a man who’d face wealthy developers

wearing an ancient combat jacket and mud-caked jeans – but somehow this meeting felt different. Caroline Varley wanted an archaeologist to advise her and he was sure that she’d be expecting some gentleman antiquary wearing

tweed and a bow tie. Not a working field archaeologist like Neil Watson.

That wasn’t to say that he hadn’t made a stab at sartorial respectability. He was wearing his only pair of half-decent trousers

and he’d managed to fish out a proper shirt from the back of his small wardrobe. He’d even found a tie lurking in the detritus

at the rear of his sock drawer. On discovering the crumpled state of his rarely worn clothes, he’d been tempted to ring his

friend Wesley who always seemed to dress smartly when he was out interrogating criminals and was sure to have something he

could lend him. But a session with the steam iron had done the trick and now he felt uncomfortably smart. Even his best shoes

had seen a bit of polish and his long hair had been washed the night before and attacked with a brush.

He straightened his tie as he climbed out of the car. The summons to Varley Castle had come via a letter handwritten on expensive

deckle-edged notepaper. The missive had stood out from the rest of the Unit’s routine correspondence – the bills and the reports

– and Neil had stared at it for a while before opening it. It was rare nowadays to receive a handwritten letter, rarer still

to receive such an upmarket one.

He locked the car door – he doubted whether such a security measure would be necessary in that particular location but it

was hard to break the long-ingrained habit of suspicion – then he approached one of the most imposing front doors he had ever

seen: studded oak and tall enough to admit a giant. But before he could raise the great lion-head knocker – not much smaller

than the real thing – the door swung open silently.

Standing there in a pink cashmere sweater and jeans was a tall, slim woman, not much older than himself. She had a long face

– horsy some would say – and wavy brown hair, newly washed and a little wild. Her nose was too large and her mouth too wide

but, in spite of this, there was something attractive about her – but Neil didn’t know quite what it was.

‘Dr Watson, I presume.’ Her voice was deep, her accent well bred but not cut glass.

Neil held out his hand. ‘Ms Varley?’

‘Caroline please.’ She gave him a businesslike smile but he knew from her eyes that she was assessing him, weighing up his

suitability.

‘I’m a bit early.’

The corners of Caroline’s mouth twitched upwards in a crooked smile as she stood aside to let him in. ‘Eagerness. I like that

in a man. Come through.’

He found himself in the entrance hall, granite-walled like the exterior. But here the stone was relieved by a set of large

tapestries which, in spite of the faded colours, gave the illusion of warmth. He was struck by the abundance of artefacts

from ancient Egypt displayed about the place: a large stone figure of a hawk-headed god; various smaller statues of gods and

mortals; chairs, chests and a model boat, complete with rowing slaves. A cluster of stone jars with animal-headed lids stood

near the doorway: Neil recognised them as Canopic jars, designed to hold the organs of a mummified body, and the realisation

of their purpose made him give an involuntary shudder.

Either side of a massive stone fireplace stood a pair of life-sized Egyptian figures in black and gold, the sort left in tombs

to keep the dead company. The figures watched his progress with painted eyes as Caroline led him into a book-lined room, the shelves packed with ancient volumes. The room was cosier than one would expect from the outside appearance

of the castle with polished oak furniture and rich Turkish rugs on the dark wood floor. Caroline invited him to sit on a worn

velvet sofa.

‘Would you like coffee? I usually have one myself at this time of day.’

Neil nodded. He felt nervous, although he wasn’t quite sure why, and coffee would give him something to do with his hands.

He had expected Caroline to tug the tasselled bell pull that hung by the great stone fireplace but, to his surprise, she excused

herself and left the room. It seemed that she was going to make the coffee herself. He had assumed there’d be some kind of

housekeeper at least.

He took advantage of her absence to look around. In the corner stood a grand piano supporting the traditional assortment of

family photographs – he’d seen a similar arrangement in almost every stately home he’d ever visited. But instead of smiling

grandchildren and the owner of the house shaking hands with a member of the Royal Family, these photographs were mostly black

and white. And most of them featured one particular man.

This man was middle-aged, well built with the kind of weather-beaten good looks normally associated with heroic explorers

of Queen Victoria’s reign. He sported a fine moustache and in each photograph he posed triumphantly next to some notable Egyptian

site: at the great pyramid of Cheops; in front of the mortuary temple of Rameses II; dwarfed by a colossal statue of a long-dead

pharaoh. There were photographs of him with other men wearing light suits and pith helmets flanked by native Egyptians in

their flowing robes, some smiling, some sullen. These were images of a more romantic age of flamboyant gentleman amateurs and great

discoveries – a world away from the type of archaeology Neil knew.

He had heard of Sir Frederick Varley, of course. His name had cropped up occasionally at University but, as the topic of Egyptology

hadn’t featured heavily in the syllabus he’d chosen to follow, he knew only the bare facts about the great man’s achievements.

Varley had financed various expeditions to the Valley of the Kings and he had been a keen participant in the excavations,

although he always employed professional archaeologists to do the scholarly work and locals to do the physical digging.

However, for all his efforts, Varley had never experienced the glory of a really big find: he had been no Lord Carnarvon discovering

Tutankhamen’s virtually intact tomb. But he had a respectable record none the less, including the discovery of the tombs of

a twentieth-dynasty queen, complete with intact sarcophagus, and the richly decorated tomb of a chief musician in the court

of Amenhotep II when the culture of the New Kingdom was at its peak. For a gentleman amateur, Frederick Varley hadn’t done

too badly.

Neil walked slowly around the room. Most of the books around the walls were connected in some way with ancient Egypt and there

were several small glass display cases containing jewels and amulets. All, no doubt, taken from tomb; objects intended to

adorn the dead. Neil had always felt that the Egyptians had been obsessed by death and the preservation of the body for the

afterlife: perhaps that’s why he’d preferred other branches of his chosen profession.

‘I see you’re admiring my great-grandfather’s collection.’

Caroline’s voice made Neil jump. He turned round with what he feared was an inane grin on his face and saw her standing in

the doorway holding a large wooden tray. He hurried over to her, almost tripping over a well worn rug, and took the tray,

hoping to impress her by good manners. He wasn’t sure why he felt so eager to make a good impression: after all, it wasn’t

really something that would benefit the Unit. But there was something about this woman that made him feel he had to be on

his best behaviour.

‘In fact that’s why I contacted your Unit. I thought it would be the best place to start,’ she said as Neil placed the tray

carefully onto a side table. ‘My uncle died three months ago and I inherited the house and estate.’

‘Wow.’ Neil temporarily forgot to play the cool professional.

‘It’s more a burden than a blessing, I’m afraid. I’m negotiating for the National Trust to take the place over. There’s no

way I can afford the upkeep.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Neil.

‘Don’t be. It’s an old mausoleum of a place.’

‘Did you move in as soon as your uncle died?’

‘More or less. I didn’t like to think of leaving the place empty.’

‘Do you live here alone?’

She didn’t answer for a few seconds. ‘I have a flat in London – bought it as soon as my divorce came through – so I’m used

to fending for myself.’

Her answer seemed a little evasive and Neil wondered if she was hiding something … or someone.

‘What did you do in London?’

‘I was PA to a company director.’ She paused. ‘And the director in question was a shit. When I inherited this place I told him where he could stick his job.’ She smiled at the memory.

‘Did you come here much as a child?’

She looked him in the eye as though she was about to share a confidence. ‘My mother said that when I was very young I used

to start screaming as soon as the car drove through the gates. The place really used to scare me.’ She paused. ‘Bad things

happened here and I’ll be glad to get rid of it.’

‘What bad things?’ Her words had aroused his curiosity.

She waved a hand dismissively and picked up her coffee cup, a chunky mug with a colourful design: Neil had expected bone china.

‘It’s not important.’

Caroline straightened her back, suddenly businesslike. Neil had caught a brief glimpse behind the confident mask but now the

defences were up again. Something in that house made her uncomfortable and he suspected that her decision to give away her

inheritance hadn’t been influenced solely by financial considerations.

‘The thing is,’ she began, ‘my great-grandfather amassed this huge collection of Egyptian artefacts. The castle’s crammed

with the things and they’re not comfortable to live with, to put it mildly.’

‘I can understand that,’ said Neil with sympathy. It seemed that the hall and the library only contained a fraction of the

collection. Elsewhere there would be more. And as the ancient Egyptians had put a lot of energy into creating and furnishing

magnificent tombs, most of what was discovered by later generations was connected with death and funerary rites. The walls

of this forbidding house were filled with the memento mori of an ancient civilisation. And this thought made him feel uncomfortable.

‘The main collection’s upstairs but it’s probably best if we start down here and tackle that later. I’d like you to go through

everything, Dr Watson. I need to know what’s here … and if it has any value. There’s always a chance the National Trust

will want to keep the collection here intact of course, or it might go to a museum, but I’d like to know what I’m dealing

with. Just an initial assessment. Nothing too detailed.’

He saw her looking at him expectantly. He was the first port of call. And he felt reluctant to admit his ignorance and tell

her she was wasting her time. But he knew it was best to be straight with her. ‘I admit I’m not an expert on this sort of

thing but I’ll have a quick look round and, if necessary, I’ll get in touch with someone who can

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...