- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

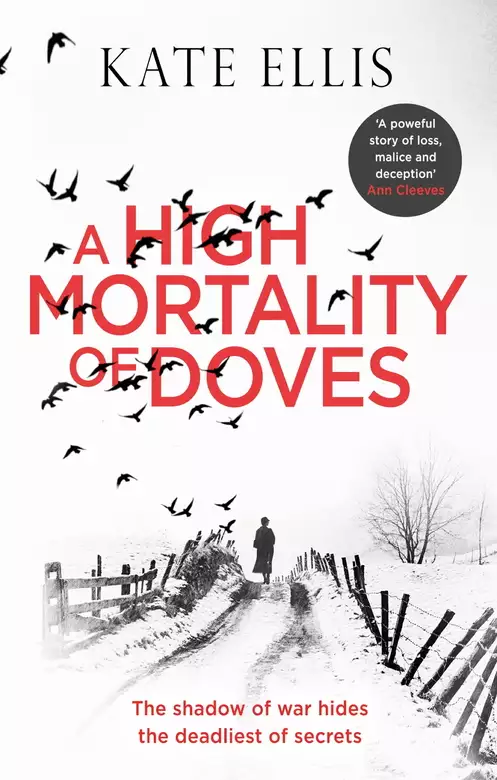

1919. The Derbyshire village of Wenfield is still coming to terms with the loss of so many of its sons, when the brutal murder of a young girl shatters its hard-won tranquillity. Myrtle Bligh is found stabbed, her mouth slit to accommodate a dead dove. During the war Myrtle volunteered as a nurse, working at the nearby big house, Tarnhey Court. When two more women are found murdered, Inspector Albert Lincoln is sent up from London. Albert begins to investigate and the Cartwright family of Tarnhey Court and their staff fall under suspicion. With rumours of a ghostly soldier, the village is thrown into a state of panic – and with the killer still on the loose, who will be next?

Release date: November 3, 2016

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A High Mortality of Doves

Kate Ellis

His mother had broken the news to his sweetheart, Myrtle, soon after she’d received the telegram. She’d staggered round to her house and waved the small piece of paper in her face, too shocked with grief to speak, too stunned to cry.

Not long after this, a letter arrived from his commanding officer, saying how he’d died bravely and felt no pain during his last moments on Earth. All the letters received by relatives said the same but nobody dared to challenge the thin comfort of the words because nobody could bear to disbelieve it. Myrtle Bligh certainly couldn’t and neither could Stanley’s mother who’d read the letter over and over until the fold in the paper began to fray and tear. And now she kept it safe in a biscuit tin, in pride of place on the mantelpiece like a holy relic.

The Stanley of Myrtle’s imagination, the image she thought of when she lay in bed waiting for the sleep that didn’t come, had now become transfigured into a legendary hero. She saw him bathed in a halo of glory as he went over the top, falling gracefully and painlessly as the enemy bullet found his heart. In her imagination she saw his corpse lying on the grass of the battlefield – fresh green grass, never mud – quite unmarked apart from a neat, bloodless bullet hole in his khaki tunic. She saw his eyes closed in sweet repose and his arms folded piously across his chest. Resting in peace. She couldn’t bear to think of that body she’d loved bleeding and torn apart by shells and shrapnel. And the letter had said his end was painless so she had to believe it.

She knew Stanley was dead because he’d spoken to her from the Other Side when she’d visited the medium in New Mills with his mother. She’d sat at the round table in the darkness, clasping the clammy hand of a man whose son was missing in action. Before that evening the only man whose hand she’d held had been Stanley, and it had felt odd to be doing the same with a balding stranger who smelled of sweat and fear.

As the medium, a fat woman in rusty black with a piping, little-girl voice, sank into a trance her voice suddenly deepened and she delivered her messages in the voice of a man: her spirit guide who told her that Stanley was smiling and blissfully happy on the Other Side. Everybody there received the same message. There had been no mention of pain. No fires of hell and damnation. The dead existed in eternal peace. And Stanley was amongst them.

It was impossible that Stanley was still alive. The army always told the truth about things like that and if they weren’t sure, they said ‘missing in action’. Or ‘missing, believed dead’. Some families in the village had received letters containing those terrible words. But if the letter said someone was dead, they were dead. Weren’t they?

Only now she wasn’t so sure. Not since she’d received that letter of her own that appeared to prove the first was a lie. It had been pushed through her door, her name printed in clumsy letters on the envelope. She hadn’t recognised the writing but once she’d torn it open she’d known it was from him, and she put the change of handwriting, the roughly printed letters, down to some dreadful injury he’d sustained during those terrible years of war.

I am alive, the letter said. Meet me in Pooley Woods at eight tonight. I’m in trouble so don’t tell anyone. Bring this note with you, for if it should be found it would be the worse for me. S.

Trouble could mean anything, of course, but she’d heard of men who’d deserted and were hunted down like animals. Cowards. She’d always hated cowards. When the men had marched proudly through the High Street that day, cowardice had seemed like the worst sin imaginable. Worse than murder. Surely Stanley, her wonderful sweetheart, sainted by his long absence, couldn’t be guilty of such a thing. It was impossible.

Perhaps the words meant something else. Perhaps he’d been on some secret mission and there were still enemy spies out there pursuing him, even though the conflict was over.

She went through all the possibilities in her head as she peeled the potatoes on her mother’s instructions, hardly aware of slicing into the starchy lumps before throwing them into the salted water. But at no stage did it occur to her that she wouldn’t go and meet him as he asked. If a miracle had occurred and Stanley had survived and returned to her, she wanted to know. She wanted to kiss those lips again. She wanted to marry him as they’d promised before he left. A small flame of hope had been reignited. How could she snuff it out now?

Without letting her mother know where she was going, she put on her coat and sneaked from their small stone cottage at the heart of the village, praying nobody would see her. It was almost dark and she felt nervous yet excited as the hard soles of her button boots clicked on the cobbles of River Street. Once she’d crossed the old stone bridge that spanned the river, she hesitated a moment when she saw a group of men entering the Cartwright Arms, their weather-beaten faces set with determination beneath their soft cloth caps. Working men in search of refreshment. She recognised some of them as men who’d worked on Wilf Fuller’s farm with her dad… before he’d gone away to France and never come back. She didn’t want them to see her and she was relieved when they didn’t look in her direction.

As she turned left down the High Street she cursed the heels of her boots, clicking so loudly and drawing attention. Not having been brought up to lie and deceive, she was unused to subterfuge. ‘Tell the truth and shame the Devil’ was one of her mother’s favourite sayings. But if Stanley wanted secrecy, there must be a good reason.

It wasn’t long before she reached the woodland on the edge of the village; the small area of trees amidst the fields that had always been the favoured place for courting couples and seekers of firewood. Pooley Woods had been her and Stanley’s special place. They had met there so often to kiss – no more than kiss because that sort of thing would have to wait for their wedding night – and talk. But that telegram from the War Office had robbed her of the happy future she’d dreamed of: the wedding; the love-making; the companionship; the children. All gone. Until now.

Suddenly she was filled with hope; replenishing her spirits like water on a drooping plant. Her footsteps quickened as she heard the church clock chime. Eight o’clock. The time her fate would become clear.

As she entered the trees she heard a sound. A flutter of wings in the canopy of budding leaves above. A bird. She couldn’t see it but she could hear its panic and she took a deep, calming breath. She walked on to the clearing where she and Stanley used to meet, telling herself there was nothing to be afraid of. She’d been in these woods a hundred times or more. But she’d never gone there alone before.

Then she saw him. A shape outlined in the dim dusk light filtering through the branches. He was standing quite still between two trees. Waiting in the shadows. He was watching her but he made no attempt to speak. She thought he was in uniform but she couldn’t be sure. Suddenly she wasn’t sure of anything any more.

She called his name. ‘Stanley?’ The word came out as a question because he looked different somehow. But it was a long time since she’d seen him and she’d heard war could do dreadful things to a man.

He began to move, walking slowly and awkwardly towards her. Stanley had been strong and he’d moved with the grace of muscular youth, but now his whole body had shrunk and his limbs seemed stiff, like an old man’s.

‘Stanley? Is it you?’

There was no answer. He was still an approaching shape, human yet not human, and she wished she could see his face but it was too dark. As she took a step back he stopped and held out his hand as if to reassure her.

Perhaps, she thought, he’d lost the power of speech. Perhaps he’d been so horribly disfigured that he couldn’t bear for her to see. But she knew that even if he’d become a monster, she mustn’t cry. She mustn’t let him see her disappointment.

After a few moments she couldn’t help herself. Overcome with pity and love she felt herself moving towards him.

‘Stanley.’

She was a couple of feet away when she finally saw the face. It looked nothing like the one she’d expected. Instead of warm flesh, all she could see was a pair of painted, staring eyes and the parted lips of a life-sized doll. She couldn’t suppress a gasp of horror at what he’d become. Her beautiful boy. Her Stanley. Her hand shook as she raised her fingers towards the face and when they made contact, she felt it hard and cold beneath her touch.

Then she felt a sudden pain in her chest and when she lowered her eyes she saw something dark and sharp protruding from her body. A sword, perhaps. Or a bayonet. The weapon of a soldier.

She gasped the question ‘Why?’ and fell to her knees in front of him.

Although three weeks have passed since the discovery of Myrtle’s body in Pooley Woods, the police appear to be as puzzled now as they were on the day she was found.

Like most of the village, I attended Myrtle’s funeral and as I walk through the churchyard on my way back from delivering a bottle of Father’s tonic to the vicarage, I can’t help reliving that grim little ceremony. In my mind I still see the mourning flowers strewn around the grave as Myrtle’s plain coffin is lowered into the earth and her inconsolable mother sheds bitter tears for her dead daughter. It rained that day as if heaven itself was weeping.

As I walk down the churchyard path a flash of white catches my eye. When I stop I see a dead dove lying on the grave of Emanuel Beech, one of Father’s elderly patients who passed away last week. The bird’s wings are spread over the mound of soil as if it is trying to protect old Emanuel’s scrawny corpse from predators, and its snowy feathers lie stark like bone against the newly dug earth. The little beak gapes open but even death can’t rob the dove of its beauty.

I stand there for a while with my eyes fixed on the lifeless thing until the chiming of the church clock reminds me that I have to be home. If I’m late Father wonders where I am and I can’t face the inevitable questions.

Father is more anxious these days and I think it’s because of what happened to Myrtle. Ever since her body was found he’s been watching me, emerging from his study every time he hears a door open and interrogating me about my every movement. ‘Where have you been, Flora? Where are you going? What time will you return?’

After spending the war at Tarnhey Court, taking responsibility for the life and death of men braver than me, I find Father’s intrusion irritating. Nevertheless, I understand his concern. After all, Myrtle Bligh had been my contemporary, even though our relative stations in life meant that we had little to do with each other while we were growing up in the village. Of course all that changed once we both volunteered to do our bit for King and Country at Tarnhey Court and joined the VADs, those raw and inexperienced nursing auxiliaries who set aside their everyday lives and their squeamish natures to take care of the wounded. War and blood have been such levellers in our little community and Myrtle and I became colleagues for the duration, united in duty.

I confess I miss the work and our patients with their banter, born of brittle courage. Most of them were just boys, dragged suddenly into manhood by shells and bullets and their horrible disfigurements. At first the sight of their mutilated flesh robbed me of breath. But as I became accustomed to my duties, my heart and stomach hardened and I could look at them with no emotion but pity. Limbs missing, faces with no features, masses of blood and burned, mottled flesh; noses gone, eyes gone. Everything gone.

I must admit that Myrtle took to nursing those poor wounded shells of men much faster than I did. Sometimes she’d laugh at me and tell me that a doctor’s daughter shouldn’t be so alarmed by the sight of a bit of blood. She was right, of course. When I first walked through the imposing oak doors of Tarnhey Court and put on the simple blue dress, the snowy white apron and the white linen cap, I was a coward. And cowards aren’t allowed to exist in times of war, so I hid my true nature and got on with it. Matron never knew and Sister never knew. Neither did my fellow VADs. Only Myrtle witnessed me vomiting into the sluice on that first day but, as far as I know, she never gave away my secret.

Now Myrtle’s life has been cut short by a murderous attack and she sleeps her eternal sleep beneath the damp soil in the churchyard. They laid her beneath the old apple tree in the corner near the grey dry stone wall and there’s talk that her family are saving up for a headstone. I find myself wondering what it will say. Maybe something like Myrtle Bligh: born 1898 and taken from this vale of tears by a cruel murderer in 1919. May her soul be avenged. But round here I reckon they’ll choose something less brutal. Something sweet and sentimental. Not dead, only sleeping or With the angels. I doubt if her family will want to be reminded of how she met her end.

In spite of the time that’s passed since Myrtle’s death, the tragedy is still the talk of the village and beyond. Every detail has now filtered down to eager ears: how she’d been stabbed through the heart and how a dead bird had been stuffed between her pretty, rosebud lips. A dove, possibly from the dovecote on the Cartwright estate. Or so people say.

They’ve been saying a lot of other things as well. The rumour of the soldier persists and there is talk that she had a secret sweetheart who may have been married. I don’t know the truth of it because once Tarnhey Court was handed back to the Cartwrights and the patients, nurses and doctors left, Myrtle and I returned to our separate worlds – Myrtle to the tedium of the mill and me to the equally tedious task of looking after Father and his surgery.

I’ve often mentioned to Father that I should like to go away and put the skills I learned at Tarnhey Court to good use. I tell him I’d like to train properly as a nurse and work in some big city hospital but for some reason he won’t countenance the idea. ‘My dear girl, war puts us in some strange situations,’ he says, scratching his sparse hair and consulting his gold pocket watch. ‘But there is no need to prolong them now that we have the blessing of peace. The war was an aberration and it will never happen again.’

Father’s a stubborn man and I know better than to argue. I will bide my time and strike when his defences are down. One day I’ll get my way.

The police have been questioning some of the young men in the village about Myrtle’s murder. Her sweetheart, Stanley Smith, was killed on the Somme and there have been no rumours of anybody replacing him in her affections so there is no obvious suspect. Through the network of gossips, I discovered that it was Jack Blemthwaite who found her body and there are some – no not some, many – who are saying that he was responsible for her death. You know what villages are like for whispers, veiled accusations from the self-righteous lips of the women in shop queues and outside church on Sundays. They gather round any scandal like crows around the corpse of a dead sheep and I learned long ago not to give any credence to their poison. Jack Blemthwaite is simple, you see, and folk always fear the different. Luckily his mother swears he was with her at the time they say Myrtle died. But the gossips say her statement is worthless: they claim that mothers will say anything. Mothers, they say, can’t be trusted.

And there could be some truth in that because I’ve heard it said that my own mother couldn’t be trusted. Maybe one day I’ll discover why she went off without a word, leaving Father alone to care for me and John. The whisperers said she went off with a fancy man; a man who took a room at the Black Horse while he was visiting one of the mills on some unspecified business. But I was only young then and I’ve never managed to find out whether this story’s true. I can’t ask Father. I don’t want to probe the wound which must still be raw, even after fourteen years.

I think I saw this alleged fancy man once. He was youngish and slim with a bowler hat and a small moustache that gave him the look of a large and prosperous rat. This was before the war so, for all I know, he might be dead now, his body blown to pieces in some Flanders trench. And I’ve no idea whether Mother is still alive because, after that night, we never heard from her again. As far as I can gather, Father returned from visiting a patient and found her gone, along with her valise and most of her clothes. The one thing she didn’t take with her was a photograph of her children.

Whispers. Always whispers. Whispers wound like bullets. Only nobody calls a truce and nobody puts the names of the fallen on fine memorials in village squares.

The grass in the churchyard has been recently scythed and I breathe in the scent of it as I walk on towards the graves of some of the men I nursed. Men who were so sick from their terrible injuries that they had no hope of recovery. But we did our best for them, Myrtle and I and all the rest.

I pause by the graves of those poor young men and bow my head. Then, on impulse I return to old Emanuel’s grave and pick the dead dove up by its wing. It feels light, as though it has no substance; a thing of air and spirit. I carry it to the apple tree and lay it in a little hollow in the bare brown earth underneath, not too far from Myrtle’s grave. It seems right to leave it there somehow, as if it had passed away peacefully on a branch and tumbled to the ground.

My eyes are attracted by the array of wilting flowers that have been placed on Myrtle’s grave. As I catch sight of the rotting blooms I can’t help thinking of Myrtle as she was when I knew her. Petite with that sharp, pointed face of hers, always curious, always ready to chatter about other people’s business. And now she is a decomposing corpse six feet beneath the ground.

The hands of the church clock are creeping forward and I know it’s time to go. But, in spite of the chill in the air, I feel comfortable there in the churchyard. I like being near the dead.

As I walk away towards the old lych gate where the coffins used to rest on their final journey, I spot a figure on the other side of the churchyard wall. A tall, well-built young man with his cap pulled down over his eyes, as though he doesn’t wish to be recognised. But everyone knows Jack Blemthwaite. He’s unmistakable with his thick lips and his eyes bulging like gobstoppers. He looks strong. But he wasn’t sent to war with the rest. He stayed safe at home in his mother’s care, free from all danger. Some people in the village hadn’t liked that.

I walk away quickly, back to the house. Father’s evening surgery will be starting soon and he needs me.

Annie Dryden had a secret but it wasn’t one she could share with her husband, Bill. Not until she was sure at any rate. Mind you, Bill rarely spoke to her these days. When he returned home from his work at the blacksmith’s each night, he’d sit by the fire, saying nothing while she fussed around him, preparing a dinner fit to fill the belly of a working man.

When she placed the food on the table in front of him he never uttered a word of thanks and he never asked her what she’d been doing during the day. It was the same with their three girls; he took no interest in their jobs in the mill, instead focusing on his own closed world of work and the Cartwright Arms. On occasions he came home the worse for drink, something he’d never done before the war. When their son Harold was with them he wouldn’t have dreamed of it. Before that telegram came to say that Harold was missing believed dead, Bill had been a different man.

The letter had arrived with the lunchtime post while Bill and the girls were out of the house. At least Annie assumed it had come with the post. There was no stamp on the envelope so it might have been delivered by hand. Annie couldn’t be sure.

When she saw it lying on the doormat she stared at it for a while before picking it up as though it was something fearful, a paper grenade that might cause untold damage. She rarely received letters and the sight of it reminded her of the one she’d received just over a year before; the one that had arrived a few days after the telegram that changed their lives. That momentous letter had been from Harold’s commanding officer who’d expressed his deep sorrow. Some of the words he’d used weren’t familiar to her as her reading wasn’t good, and she hadn’t been able to make out the signature. But she’d recognised the sentiment. Her son was a hero and she should be proud of him. Better a hero than a coward. Cowards were the lowest of the low and being the mother of a coward would have been the ultimate humiliation.

The news about Harold had left her stunned for a while but it hadn’t dampened her spirits for long; especially once she’d convinced herself that the authorities had made a mistake. As far as she was aware, Harold’s body had never been found. But rather than assuming he’d been blown to pieces by an enemy shell, Annie had become more and more convinced that he was still alive and she assured her sceptical husband that he was probably wandering, confused and with no identity, somewhere in France, having lost his memory. She reasoned that if he hadn’t lost his memory, he’d have come home to Wenfield and his family and this assumption had kept hope alive, so much so that she kept his little bedroom, barely large enough to accommodate his single bed, as a shrine, untouched and ready for his return.

She’d stared at this latest letter for a while before opening it. Letters in the Dryden household usually heralded some official unpleasantness so she’d pulled out the sheet of paper with some trepidation and peered at the writing. Her eyes weren’t too good these days, not close up, and she’d strained to see the words. The roughly printed letters swam in front of her eyes but eventually she managed to decipher the contents.

Dear Ma, it began. I’m alive but I’m in trouble. Please meet me in the lane by Fuller’s Farm at half past seven tonight. I’ll explain everything when I see you. I don’t want anyone in the village to see me and don’t tell anyone, not even Pa and the girls. Please destroy this letter or bring it with you because if anyone finds it it’ll be the worse for me. Please, Ma, do as I ask. I love you. Harold.

Her heart lifted. She’d been right all along – her Harold was alive. But he said he was in trouble which could mean he’d taken the chance to desert when he’d gone missing. For a few moments her elation gave way to a crushing shame. How often had she chided others for their cowardice and now her own flesh and blood might be guilty of the same offence. But she’d soon banished the thought from her mind. Harold had probably been on some secret mission behind enemy lines. Most likely he knew something that still put him in danger. He was a hero. Of course he was.

Annie’s main pleasure in life had always been the exchange of gossip and information, that thrilling feeling of knowing things others didn’t. Even during the war there weren’t many things that went on in Wenfield that Annie didn’t know about, and her spirit was nourished by the secret sins of others. Even those of her so-called betters. But now she knew she had to keep her mouth shut and guard her new knowledge carefully. She wasn’t going to share the contents of Harold’s letter with anyone – not until the time was right.

When the girls and Bill returned home from work she had their dinner ready as usual, and as she bustled to and fro in the kitchen she couldn’t help touching the letter carefully hidden in the pocket of her voluminous apron to assure herself that it was still safe. Everything had to be kept as normal as possible. Nobody must suspect a thing.

Just after Bill had gone out to the Cartwright Arms, Annie Dryden told her girls that she was going out to visit a neighbour and got ready, putting on her newest hat. And just after seven she hurried from the house, more nervous than she’d been on her wedding day.

This was the moment she’d been waiting for.

Father hardly speaks at breakfast. He reads the newspaper as he’s done every day for as long as I can remember, holding it high so I can’t see his face. I remember Mother sitting in the chair opposite, her silence more eloquent than a thousand words of idle chatter. When Mother was here my parents rarely spoke to each other. Perhaps that’s why she left us on that warm May night. Perhaps that’s why she never came back.

A few weeks after Mother’s departure, Edith moved in with us. Father required a housekeeper to run his household so, as Edith had been recently widowed and was in need of employment, she seemed the ideal choice.

I was eight at the time, a precocious child who took a great interest in the books in Father’s surgery. My brother John was sent away to school, but since I was a girl, Father thought the presence of a governess was sufficient to meet my educational needs.

A succession of sad women, waif-thin and mildly shabby, had entered our old stone house near the centre of the village but none had stayed above a year. They were themselves daughters of professional men and clergy who had been unable to inveigle some man to the altar. I know them now for what they were and regret my rebelliousness and the trouble I no doubt gave them. For now I realise that they were my sisters in solitude. And since the war ended their ranks have been swelled by all those who lost potential husbands in the fields of France.

To return to Edith, it soon became clear that Father treated our new housekeeper a little differently from the governesses and the other servants. To my eight-year-old self Edith seemed old but now I know she can’t have been more than twenty-two, the age I am now. She had freckles on her face and a generous mouth. And her fine hair, the colour of straw, was always escaping her hairpins, as though it sought freedom from the confines of conformity. She was beautiful, although I didn’t recognise it at the time. But I am sure now that Father did.

Even though I was an observant child in those days, I knew little of the ways of grown-ups in matters of attraction. Now, however, I know why Father abandoned the worn tweed jacket he always wore at home once his visits to his patie. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...