- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

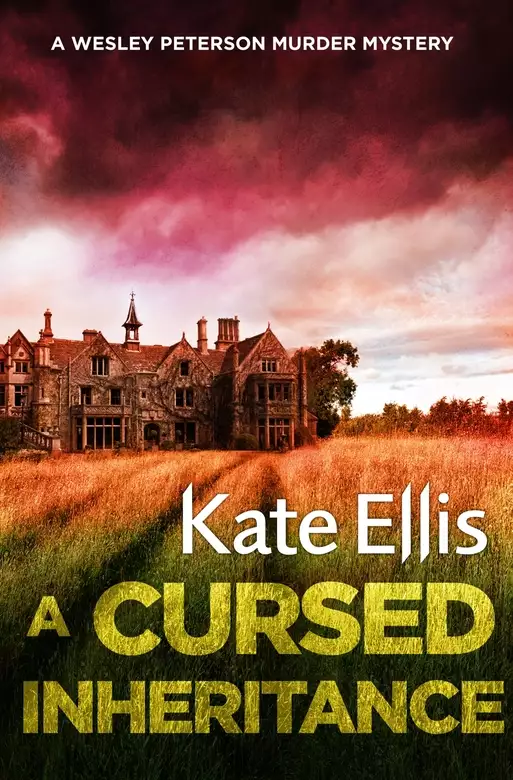

Synopsis

The brutal massacre of the Harford family at Potwoolstan Hall in Devon in 1985 shocked the country and passed into local folklore. When a journalist researching the case is murdered 20 years later, the horror is reawakened. Sixteenth century Potwoolstan Hall, now a New Age healing centre, is reputed to be cursed because of the crimes of its builder, and it seems that this inheritance of evil lives on as DI Wesley Peterson is faced with his most disturbing case yet. And when the truth is finally revealed, it turns out to be as horrifying as it is dangerous.

Release date: January 6, 2011

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 340

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Cursed Inheritance

Kate Ellis

we still favour the old ways.

We are numbered sixty-five – mostly men but some women and children – and in our company we have persons of all ranks: gentlemen,

artisans and labourers. Captain Barton hath authority over all until the sealed orders in his care are opened. Then we will

know the names of the Council that is to rule over us when we reach our journey’s end.

There were many sick in the first days of our voyage, yet I myself did not succumb. By unprosperous winds we were kept five

days in the sight of England. Then we suffered great storms, but by the skilfulness of the Captain we suffered no great loss

or danger. By the Lord’s grace we have now reached land. It is a place called Virginia in honour of the old Queen.

We entered into the bay of Chesupioc directly without let or hindrance and when we landed we found fair meadows and goodly

tall trees with such fresh waters running through the woods I was almost ravished at the first sight thereof.

I went ahead with one Joshua Morton, a large, red-faced gentleman from Dorset who travels with his brother, Isaac. This Joshua’s

wife – a most comely woman, small and dainty and a full score years younger than her husband – feared what we would find once

ashore. Her brother-in-law, a foolish man, had been telling her tales of savages and fierce wild creatures, taking pleasure

in seeing her fear and placing his fat arm around her waist. I did my best to reassure her that I am at her service.

Set down by Master Edmund Selbiwood, Gentleman, on the Nicholas this first day of June 1605.

Emma Oldchester knelt on the hard wooden floor and took the tiny figure between her thumb and index finger. When she had placed

it carefully in the drawing room she brushed back her long fair hair with her left hand and stared at the scene she had created.

She had painted the house carefully, just as she painted all her doll’s houses. But this one was different. Special. She had

tried to get every detail right, making alterations as the memories crept back. The wallpaper, the fabric of the curtains,

the exact position of each item of furniture. The blood spattered on the walls.

She recalled some details about the house – the huge oak door and the dark green walls in the kitchen – quite clearly. But

the important things were vague like a half-remembered dream. There were times when she wished she remembered more. And yet

perhaps it was better that she didn’t.

She looked down at one of the dolls lying on the table, the one dressed in a tiny cloak of black felt, the one with no face

or gender. She stared at it with unblinking eyes for a few seconds before throwing it down.

When she stood up she placed her heel on the small figure and ground it into the floor, twisting until the thing broke with

a satisfying snap.

*

‘So where are we off to, Wes?’

‘Report of a body in the river?’

DCI Gerry Heffernan sighed. ‘Life got too much for some poor bugger, I suppose.’

‘The call said it looks suspicious.’

With Heffernan slumped in the passenger seat beside him, DI Wesley Peterson drove the unmarked police car out of Tradmouth

and turned on to a narrow lane fringed with high, budding hedgerows. He had taken down the directions carefully as usual –

half a mile before Knot Creek on the Tradmouth side of the river. Unlike his boss, he liked to be ordered and organised.

When they reached their destination – a small car park next to a footpath leading down to the river – he saw that Dr Colin

Bowman’s new Range Rover and the police photographer’s battered Fiat were there already, parked next to a brace of patrol

cars. The show had begun.

The path skirted round the edge of a field and they trudged towards the water’s edge, watched by staring ewes and their small

woolly lambs. Eventually, they arrived at the river where overalled figures were working industriously beneath the overhanging

trees. The area had been taped off – a crime scene.

Following the bright flash of the police photographer’s camera, they located Colin Bowman, the pathologist. He was squatting

by a human body which lay, waterlogged and still, on the ribbon of sparse grass next to the water. When Colin spotted them

he straightened himself up and peeled off his latex gloves.

‘Good to see you both. They fished him out of the river an hour ago. Come over and have a look,’ he said, greeting them with

a genial smile. Always the perfect host. The man would be a pleasure to work with if it weren’t for the fact that every time

they met him, they had to share his company with some rotting corpse or other.

‘So what have we got?’ Heffernan asked, staring down at the corpse with distaste.

The dead man was tallish, not old, not young. Sodden jeans and sweatshirt clung to his dead flesh and his longish dark hair

was matted with river weed. The wide, sightless eyes and the open mouth gave him an expression of astonishment.

‘Healthy male. Mid thirties or thereabouts.’ Colin squatted down again. ‘He’s not been dead long enough to float to the surface

under his own steam, as it were. His clothes had been caught by the branches of an overhanging tree. See that tear in the

sweatshirt? There’s a matching wound in the flesh underneath. I think our friend here was stabbed. Probably with a fairly

narrow blade but I’ll be able to tell you more …’

‘When you’ve done the postmortem. Thanks, Colin. Don’t suppose there’s a chance that it could have been an accident? He might

have fallen on a spike or …’

Colin smiled. ‘You know the score, Gerry. I won’t know for certain until I’ve had a closer look. You’ll just have to be patient.’

Heffernan pulled a face. Patience had never been his strong point.

Wesley turned to a young uniformed constable, the sort people have in mind when they complain that policemen are getting younger

– this one looked all of fifteen. ‘Who found him?’

‘An artist, sir.’ The constable’s winter-pale cheeks turned red. ‘He was painting when he spotted the body in the river and

he dialled 999 on his mobile, sir. He’s over there.’ He pointed to a man who was deep in conversation with a uniformed officer.

Heffernan grunted something incomprehensible and turned away. But Wesley gave the young man what he judged to be a sympathetic

smile. The lad seemed keen. No harm in a bit of encouragement.

‘Thank you, Constable …’

‘Dearden, sir.’ He blushed again. He had heard of Inspector Peterson, the only black CID officer in the local force, but this was the first time their paths had ever crossed.

Gerry Heffernan was making a beeline for the man Dearden had pointed out; a stocky man in his early sixties with long grey

hair tied back in a ponytail. He wore a paint-stained, Breton smock which marked him out as an artist as much as a uniform

labels a police officer. Wesley followed his boss. The old police adage that the person who finds a body usually becomes the

prime suspect hardly seemed to apply in this case. But more surprising things had happened.

Heffernan stayed silent while Wesley asked the necessary questions but, as expected, the answers weren’t much help. The artist

had been setting up his easel when he noticed what he thought was a bundle of old clothes caught up in overhanging branches.

On closer inspection he realised it was a dead body so he rang the police on his mobile phone like a good citizen. The artist’s

hands were shaking. He looked as though he needed a drink.

Wesley concluded that he had probably been in the wrong place at the wrong time so, after thanking him for his cooperation

and noting his home address, he told him he could go. Heffernan, however, was frowning at the unfortunate man as though he

suspected him of all manner of heinous crimes from the Great Train Robbery to the Jack the Ripper murders. But he said nothing

so it seemed that he agreed with Wesley’s verdict.

When the artist had gathered up his possessions with clumsy haste and scurried back to his car, Wesley and Heffernan were

left on the river bank, staring at the grey, flowing water as the undertakers zipped the body into a bag and placed it on

a stretcher. It had probably been a pointless exercise to tape off this section of the bank: the crime had most likely been

committed elsewhere and the body carried there by the river’s treacherous currents.

‘Have they found any ID?’ Wesley asked hopefully.

The chief inspector shook his head. ‘In an ideal world, Wes, he’d have his name and address tattooed on his backside. But …’

Wesley smiled and turned away. In his world things were never that easy.

Mrs Geraldine Jeffries sat in her room on the first floor of Potwoolstan Hall, staring at the large patent leather handbag

that lay open on the bedspread. She’d checked its contents three times and she’d searched her drawers and wardrobe. She wasn’t

as young as she used to be and sometimes she forgot where she’d put things – but two hundred and fifty pounds in twenty-pound

notes and the diamond ring her late husband had given her for their silver wedding anniversary … Geraldine Jeffries had

always kept her hand firmly on her valuables.

They had been there first thing that morning – she had checked – so they’d been taken while she was down at breakfast. There

were no locks on the doors at Potwoolstan Hall, something Mrs Jeffries had complained to Mr Elsham about on her arrival. He

had assured her that, rather than being an oversight, it was a symbol of openness and trust. And this was the result.

She stood up, her thin scarlet-painted lips pressed together in a determined line. She didn’t care what Elsham said or what

excuses he gave – she was going to insist that the police were called.

And if he refused, she’d call them herself. All the Beings had been obliged to give in their mobile phones on arrival at the

Hall, but Mrs Jeffries would walk to the nearest village to make the call if necessary, in spite of her arthritis.

She had been robbed.

Pam Peterson slammed the phone down. Wesley was working late again because some inconsiderate corpse had found its way into

the River Trad. She lifted the howling baby out of her cot, seething with resentment. She needed Wesley there, just to take

over for a couple of hours, to relieve the pressure. He was fond of telling her that she was lucky to have her mother near by, but she was always quick to

point out that Della was usually more of a hindrance than a help.

The doorbell rang just as she was making her way downstairs, carrying baby Amelia over her shoulder, and when she reached

the hall she held on to Amelia’s small, soft body with one hand while she opened the front door with the other.

‘Wes not about?’ Neil Watson stood on the doorstep with a bashful grin on his face.

‘He’s at work.’ She hesitated. ‘He’s just called to say he’ll be late home … again. Come in.’

As Neil brushed past her, she felt there was something different about him, but she wasn’t sure what it was. Then it came

to her. Ever since they’d met at university, Neil had invariably worn ancient jeans, usually stained with the mud of some

archaeological dig or other. But today the jeans were spotless and so were the white trainers and black T-shirt. Neil had

cleaned up his act. Pam wondered fleetingly if it was for her benefit but then pushed the thought out of her mind.

‘Shame. I was hoping to see him before I went.’ Neil and Wesley had studied archaeology together at Exeter University. They

had shared a flat and in those half-forgotten, distant days Pam had abandoned Neil, the dreamer, for Wesley, the practical,

quiet spoken one.

Pam led the way into a living room littered with toys and baby equipment; the detritus of early childhood. As she put Amelia

into her baby chair, she held her stomach in, conscious that she hadn’t yet lost the weight she had gained during her pregnancy.

Wesley assured her that he didn’t mind. But sometimes she suspected that he was too busy to notice. Or maybe he just didn’t

care.

‘So where are you going?’

Neil sat down, his eyes aglow with excitement. ‘I’m off to the States,’ he announced. ‘There’s an excavation at a place called Annetown in Virginia. Some of the first settlers landed there.’

‘The Pilgrim Fathers?’

‘No … before their time … around 1605.’

Pam smiled. Neil might be vague about most things but history was an exception. ‘How long will you be out there?’

‘Only three weeks initially. Depends on the powers that be. It’s a sort of exchange: one of their archaeologists is coming

over here to see how we do things. I volunteered to take part because there’s a Devon connection. It was too good an opportunity

to miss really and …’ He hesitated. ‘How’s, er …’ He pointed in the baby’s direction. It was typical of Neil to have

forgotten her name.

‘Amelia. She’s fine. You were going to say something? And …?’

Neil studied his hands. The nails still bore traces of soil, an occupational hazard. After a few moments he looked up. ‘I

went up to Somerset to see my grandmother last weekend.’ There was a pause and Pam wondered what was coming next. ‘She’s really

ill. Cancer.’

‘Oh I’m sorry,’ Pam said automatically. ‘Should you be going to the States when …?’

‘She wants me to go. She’s asked me to do something for her while I’m over there.’

‘What?’

Neil hesitated. ‘She’s asked me to contact someone.’ Pam sensed that Neil wasn’t altogether comfortable about his mysterious

mission and this made her curious. But before she could question him further, Amelia decided they’d talked long enough and

began to howl. Neil looked awkward; babies were uncharted territory for him. He mumbled something about having to go and took

his leave, bending to kiss Pam on the cheek.

She stood up and flung her arms around him. ‘Take care,’ she whispered in his ear, ignoring Amelia’s urgent cries.

He broke away gently. ‘I’ll email you. Tell you how I get on. Gives Wes my regards,’ he said before walking out to his car.

Pam stood at the front door with Amelia grizzling in her arms and watched him drive off, staring at his old yellow Mini until

it disappeared out of sight round the corner. And experiencing an unexpected feeling of loss.

There was a hushed air of expectancy in the CID office when Wesley and Heffernan returned. Word had got around on the ever-efficient

office grapevine that the body in the river was a murder victim. But until Colin Bowman had given his definitive verdict there

wasn’t much they could do. Apart from discovering the dead man’s identity and tracking down his next of kin.

Wesley was wandering back to his desk when a voice behind him made him jump.

‘Sir.’ Wesley swung round and saw DC Steve Carstairs leaning on a desk with a sheet of paper in his hand. He was wearing his

black leather jacket as usual: Wesley had concluded long ago that he probably slept in it. ‘There’s been a report of a theft

at a place near Derenham; calls itself a healing centre. Money and jewellery taken from a woman’s room. It sounds similar

to those others. You know, the Dukesbridge health spa and that arts place outside Neston. And that cookery place in Morbay.

I reckon there’s a pattern.’

Wesley looked at him, surprised. It wasn’t often Steve used his imagination.

‘Well, if you’re free you’d better get round there. Let me have a report when you get back. And get a list of residents and

staff, will you? See if there’s anyone staying there who was at the other places.’

‘It’s Potwoolstan Hall,’ Steve said significantly with what Wesley thought might have been a wink.

Wesley looked blank. The name meant nothing to him.

But Detective Sergeant Rachel Tracey, who had overheard the conversation,

took pity on him. Wesley was from London after all. He could hardly be expected to be familiar with every major crime that had been committed in his adopted

county over the past twenty years – even one that had passed into local folklore so that the very name of the Hall was synonymous

with evil and death.

She ran her fingers through her hair before she spoke, a subconscious action. ‘It’s a big old house near the river halfway

between here and Neston. About twenty years ago the housekeeper there shot the family she worked for then she shot herself.’

Wesley frowned. ‘That rings a bell.’

Rachel leaned forward. ‘Every so often there’s a newspaper article or a TV programme about it. The usual rubbish. Was it part

of some satanic ritual because the woman who killed them had nailed dead crows to the doors? Was she a member of a local coven?

That sort of thing.’

‘So it passed into local mythology?’ Wesley knew the public appetite for horror stories as well as the next man.

Rachel smiled. ‘You could say that.’

‘So what’s this about a healing centre?’

‘The Hall was turned into a healing and therapy centre a few years ago. Very New Age,’ she added with a slight sneer: Rachel

Tracey, a farmer’s daughter, was a down-to-earth young woman who had no time for anything she considered to be silly or pretentious.

‘It stood empty for years after the murders, which is understandable, I suppose. Who’d want to live in a place where six people

were killed like that?’

‘Who indeed?’ said Wesley, starting to edge away. Interesting though this gruesome slice of local history was, he had present-day

misdemeanours to deal with. The corpse in the river had to be his priority before the trail, if any existed, went cold on

them.

‘You could still see the bloodstains years after it happened,’ Steve said with relish. ‘I had some mates who broke in when

it was empty and they …’

Wesley turned away. The last thing he needed was to hear tales of Steve’s misspent youth. Steve caused him enough trouble

as it was. ‘Well, you’d better go round there and see what’s been stolen. They might show you the bloodstains while you’re

at it.’ He grinned. ‘But if they charge you for the privilege, don’t claim it on expenses, will you?’

Rachel took a deep breath. ‘I’ll go with him. I could do with getting out of the office.’

Steve scowled, suspecting a conspiracy; that Rachel was really being sent to keep an eye on him. He made for the door, trying

not to let his disappointment show. The theft would be a boring routine matter and if he was stuck with Rachel that ruled

out a visit to the pub on the way back. But at least he’d get a good look at Potwoolstan Hall.

When Steve and Rachel had gone, Wesley made for Heffernan’s office. The DCI would want to be told about this new distraction,

so that he could complain about it if nothing else. Wesley poked his head round the door.

‘Just thought you’d like to know, Steve’s on his way to investigate a report of a theft.’

Heffernan shuffled his paperwork. ‘Can’t someone from Uniform deal with it?’

‘It sounds as if it might fit the pattern of those others. Same MO – money and jewellery stolen from a guest’s room. This

latest one’s at a place called Potwoolstan Hall. Steve mentioned the famous murders.’

Heffernan raised his eyebrows. ‘Did he now?’ He sat back and there was a long silence as he stared into space. Finally he

spoke. ‘I was sent over there as a raw young constable to patrol the grounds not long after I joined the force. Not something

you forget in a hurry.’

‘Rachel said the housekeeper shot the family she worked for then shot herself.’

‘That’s the sanitised version. It was a bloodbath. She blasted the elder daughter’s fiancé with a shotgun in the hall – almost

blew his head clean off: blood and brains every-where. Then she shot the son, the daughter and the parents before killing herself in the kitchen.’

‘What made her do it?’

Heffernan shook his head. ‘There’d been some sort of row but I can’t remember the details.’

‘Rachel said the Hall’s a healing centre now.’

‘So I heard. It was empty for years so they probably bought it at a knockdown price.’ He sighed. ‘So what exactly has been

stolen?’

‘Money and jewellery. That’s all I know. No doubt Steve’ll find out the details.’

‘I wouldn’t bet on it,’ Heffernan mumbled under his breath.

The sound of the doorbell made Emma Oldchester jump. She wasn’t expecting visitors. She put the final touch of brown paint

on the tiny staircase before wiping her stained hands on her apron and making her way downstairs.

She often wished they had a glass front door instead of the solid wood one Barry had chosen so she could see who was calling.

She had asked Barry to fit a spy hole but he had never got round to it. She hesitated, her hand on the latch. Surely it wouldn’t

be him. He wouldn’t visit without warning. Cautiously, she slipped the security chain on and opened the door a few inches.

‘Hello, Emmy, my pet. Aren’t you going to let me in?’

Relieved, she took the chain off and flung the door wide open. ‘Sorry, dad, I thought … I thought you might have been

him.’ She stood on tiptoe to kiss the newcomer, a big, weather-beaten, man with a shock of grey hair and a beard that tickled

her face.

‘Has he been in touch again?’

‘Not for a couple of days. I expected …’

‘I told him I didn’t know anything. Perhaps he’s given up.’

Emma began to chew at her nails.

‘Look, Em, you don’t have to speak to him if you don’t want to. Tell him to get lost. Let sleeping dogs lie, that’s what I say.’

Emma made her way into the small, neat lounge and the big man followed.

‘Maybe I won’t. Barry says I shouldn’t. Maybe I’ll just tell him I don’t want to see him if he phones again.’

There was an awkward silence. Joe Harper stared at his daughter. She looked so fragile, so vulnerable. Just as she’d always

looked.

‘How are your houses going?’

Emma forced a smile. ‘It was a good idea of Barry’s, the website. I’ve got four new orders through it: one from Wales, two

from London and one came in yesterday from a lady in Tradmouth. She wants a traditional Devon cottage for her daughter’s birthday.’

Joe smiled. ‘You’re doing well, maid. I’m proud of you.’ He reached out a large hand and brushed a strand of fair hair off

her thin, pale face. ‘Doll’s houses have always been your thing, haven’t they?’ Joe’s face clouded, as if some sudden unhappy

memory had sprung into his mind.

Emma took his hand in hers and squeezed it. She wouldn’t mention what she was planning. The last thing she wanted to do was

to worry him.

Colin Bowman was due to conduct the postmortem on the unidentified body from the river the following morning, but until then

they had to be content with idle speculation. According to Gerry Heffernan, who was an experienced sailor and knew about these

things, the body probably went in further up the river towards Neston. Now all they had to do was to find out exactly where.

Heffernan had checked with the harbour master and the coastguard just in case anything untoward had been reported by any of

the river’s many sailors. But there was no word of anything out of the ordinary. The victim might have been murdered on a

boat and the body thrown overboard. Or else he might have been thrown into the river after an attack on dry land. Either way, Wesley’s workload was due to expand at an alarming rate. He hoped Pam would understand. But somehow

he feared that she wouldn’t.

The perfunctory search of the dead man’s pockets on the river bank had yielded no clue to his identity and Wesley suspected

that the killer had stripped the corpse of belongings to make identification – and his life – more difficult. The next step

was a trawl through the missing persons reports. DC Trish Walton made a start.

Gerry Heffernan emerged from his office and announced that it was lunchtime. Wesley’s morning walk by the river had given

him an appetite and somehow, by unspoken agreement, he and Heffernan found themselves in the Fisherman’s Arms on the receiving

end of two pints of best bitter and two large hotpots which steamed temptingly in oversized bowls. Wesley tucked into his

enthusiastically. Since Amelia’s arrival in the world, hearty meals were in short supply at home and he and Pam existed on

ready meals and takeaways. But then, as Pam normally worked full time as a primary school teacher, things hadn’t been much

better before Amelia’s birth. Only in the school holidays had the Petersons ever experienced anything resembling domestic

harmony.

Wesley gazed at the roaring open fire as he finished his pint. The low-beamed cosiness of the Fisherman’s Arms with its worn

red leather seats, its well-polished horse brasses and its motherly landlady, the widow of a police sergeant, who always provided

a warm welcome for members of the local constabulary, was a perfect antidote to a morning spent studying a cold corpse on

a chilly river bank. But, like a pleasant dream, it couldn’t last for ever. They had promised Colin that they’d call in at

the mortuary that afternoon. It wasn’t something they were looking forward to but, on the other hand, Colin did serve a very

decent cup of tea.

Tradmouth Hospital was a short walk away so when they had finished their meal they walked quickly down the narrow streets to keep their rendezvous with death.

‘Wonder how Steve and Rachel are getting on at Potwoolstan Hall,’ said Wesley, raising his voice to make himself heard over

the screaming sea gulls.

‘Rachel’s been quiet recently. It is something to do with that Australian boyfriend of hers?’

Wesley hesitated for a moment. ‘That was over ages ago.’

Heffernan looked at him, curious. ‘You seem to know all about it.’

Wesley felt his face burning.

‘Is it true she’s moving out of the farm?’

‘So she says.’ He knew all about Rachel’s intention to find a flat of her own in the town, away from the farm where she had

lived all her life with her parents and three brothers. She had told him about her proposed bid for freedom in great detail.

But somehow he didn’t feel like discussing it.

When they reached the hospital they followed the signs to the mortuary. Once they had passed through the plastic swing doors

a faint odour of decay masked by a heavy dose of air freshener hit their nostrils. Wesley felt slightly nauseous. It was the

same every time.

Heffernan, however, charged ahead along the polished corridors towards Colin’s office where they were greeted like long-lost

friends and provided with Earl Grey tea and biscuits made on the Prince of Wales’s own estates from organic ingredients. Nothing

but the best would do for Colin Bowman.

Colin always liked to chat – probably, Wesley thought, because his own patients were hardly in a position to be talkative

– and he asked about Pam and the children before moving on to the subject of the forthcoming wedding of Wesley’s sister, Maritia,

and her move to Devon where she had applied to work as a locum GP. It was only when the subject of Maritia’s plans had been

exhausted and Colin had made extensive enquiries about the progress of Gerry’s two children at universities up north, that he led the way to the stark white room where the body of the man from the river lay

in a refrigerated drawer, awaiting Colin’s undivided attention the following morning. They viewed the body briefly before

Colin pointed out a set of plastic bags containing the man’s clothes.

‘Nothing very exciting, I’m afraid, gentlemen. Nothing you can’t buy in any high street in the land.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...