- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

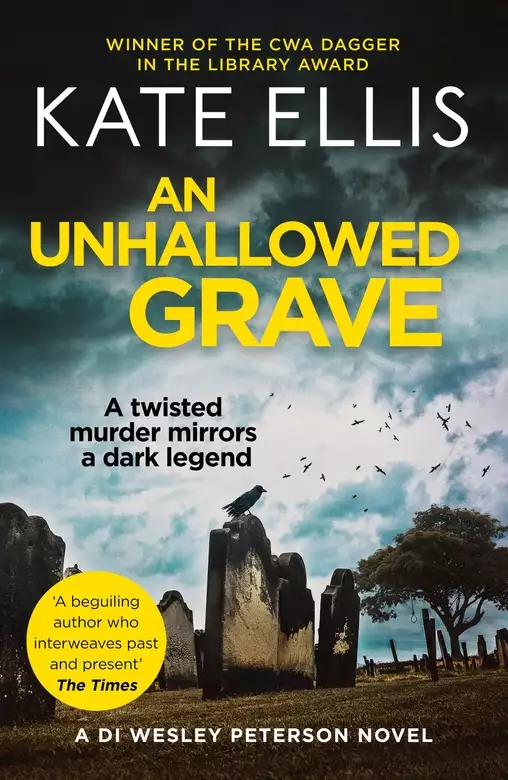

When the body of Pauline Brent is found hanging from a yew tree in a local graveyard, DS Wesley Peterson immediately suspects foul play. Then history provides him with a clue. Wesley's archaeologist friend, Neil Watson, has excavated a corpse at his nearby dig – a young woman who, local legend has it, had been publicly hanged from the very same tree before being buried on unhallowed ground five centuries ago. Wesley is now forced to consider the possibility that the killer knows the tree's dark history. Has Pauline also been "executed" rather than murdered, and, if so, for what crime? To catch a dangerous killer Wesley has to discover as much as he can about the victim.

Release date: January 6, 2011

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 209

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

An Unhallowed Grave

Kate Ellis

The jury state that John Fleccer, the blacksmith’s son and divers others did riotously and unlawfully assemble near the church

and did assault William de Monte. Fined 12d.

The same John Fleccer did then strike Ralph de Neston and drew blood on him. Fined 3d.

From the Court Rolls of Stokeworthy Manor

June 1999

The two teenage girls stood at the churchyard gate, trying to hide the nervousness they felt. In spite of the warmth of the

summer night a thin mist was blowing in from the creek, slinking and swirling around the moonlit gravestones.

‘We’ve got to do it. It’s part of the ritual. It won’t work if we don’t.’

‘I can’t see it working anyway.’ Joanne – Jo to her friends – Talbot offered her friend Leanne a cigarette which was accepted

with studied boredom.

‘Go on, Jo. It’ll be a laugh.’

‘You reckon it’ll work, do you? You think we’ll see our true loves?’ she said with heavy sarcasm. ‘It’s a bloody waste of

good grass if you ask me.’

‘Oh, go on. Me gran said it worked for her. Go on. It’ll be a laugh,’ Leanne pleaded.

Jo looked down at the tiny plastic bag in her hand. It contained a dried leafy substance. ‘Will this do?’

‘It says hemp seed in the rhyme but . . .’

‘Let’s get on with it, then. I’m not hanging round in this bloody churchyard much longer. It’s giving me the creeps.’ She

shuddered.

‘Scared, are you?’

Jo gave Leanne a withering look. ‘Piss off. ’Course I’m not scared.’

‘We’ve got to do it on the path near the church door . . . and we can’t do it till midnight.’ Leanne was relishing the experience

of being slightly, tantalisingly frightened. Anything to relieve the tedium of village life; of the dull routine of catching

the bus to Tradmouth Comprehensive each morning and hanging round the village bus shelter and phone box each night.

‘We’d better get a move on.’ Jo squinted to see her watch in the bright moonlight. ‘It’s nearly midnight now. Can you remember

that verse your gran told you?’

‘’Course I bloody can.’

The two girls giggled nervously up the church path, not daring to look left or right. The mist prowled like lean white cats

around the lichened tombstones.

Jo’s hand was shaking as she handed the plastic bag to Leanne. ‘This had better bleeding work.’

Leanne opened the bag. ‘We walk towards the church door scattering it. Then we look round. That’s when we see . . .’

‘Get on with it. Hurry up.’

Leanne emptied the contents of the bag into her outstretched palm, then she began to walk slowly, ceremoniously, towards the

ancient church, scattering the leaves onto the path.

‘Hemp seed I sow. Hemp seed I sow. He that will my true love be, come rake this hemp seed after me,’ she pronounced solemnly.

‘Now we look round,’ she added apprehensively, dreading an encounter with her future lover less than her friend’s sarcastic

disdain when the ritual didn’t work.

As the girls turned slowly, they saw a movement. Something white swayed from the branch of a large yew tree to their left.

They stared for a few seconds before they realised that this was no vision of the man of their dreams.

The body hung there, twisting in the breeze that was blowing the mist in from the creek.

It was Jo who let out the first, night-shattering scream.

At ten past midnight Julian D’estry – he had added the apostrophe to impress clients – poured himself another glass of Chardonnay

and waved the bottle at the lithe blonde who lay, supine, on the adjacent sunlounger.

Monica Belman shook her head. ‘I’m going for another swim.’ She sat up and reached across to touch Julian’s bare stomach.

Her hand slid lower but he grabbed it before it reached its target. ‘Not now.’

Monica pouted in exaggerated disappointment. ‘What’s the matter?’

‘I’m a bit stressed out. Busy week.’

‘That’s why we come down here. To relax . . . to get away from all that. Come on. What’s wrong?’ She knelt up on her sunlounger and began fumbling with the back of her bikini top. ‘I know the perfect cure for stress.’

‘What?’

‘Wait and see.’ She discarded her top and slipped elegantly out of her bikini bottom – something most women are incapable

of doing with any panache. Then she approached the edge of the pool and, after looking over her shoulder to make sure Julian

was taking in the view, plunged her slender, naked body into the chlorinated blue waters of Worthy Court’s communal indoor

swimming pool.

Julian propped himself up on his elbow and watched Monica appreciatively while he sipped his Chardonnay.

‘Put some music on,’ shouted Monica from the pool, floating neatly on her sunbed-bronzed back.

Julian obliged, placing a CD expounding the merits of ‘sexual healing’ on the portable player by his side.

‘Turn it up. Right up. It’ll get us in the mood.’ Her voice held a cockney twang and more than a hint of erotic suggestion.

Julian obeyed and, after a few minutes of watching Monica frolicking mermaid-like in the water, pulled off his swimming trunks

and joined her in the pool. He swam up to her and she flipped onto her back, a come-hither look in her bright blue eyes.

‘Listen to the sound quality of those little speakers – it pays to buy the best,’ he called over the suggestive rhythm.

‘What? Can’t hear you over the music,’ Monica replied. She had no need of conversation. She reached for Julian’s arm and pulled

him towards her, her hand wandering downward to discover that the mad Friday evening drive from London to Devon had taken

its toll on his libido. Monica, not one to give in without a fight, attached her mouth to his as the music that echoed off the swimming-pool

walls approached its inevitable conclusion.

The silence came like an explosion. Sudden. Unexpected. Shocking. Julian and Monica looked up out of the pool like a pair

of startled seals. Standing at the edge of the pool watching them was an elderly couple, well dressed and furious-faced. A

tall, grey-haired man and a younger woman with tumbling auburn tresses stood nervously behind them; the man’s hand protectively

on his companion’s shoulder as if anticipating trouble. The elderly woman defiantly held the unplugged CD player above her

head.

Monica tried to cover her embarrassment with her hands while Julian, naked and helpless, could only open and shut his mouth

in impotent rage as the CD player joined them in the water with a satisfying splash.

‘Perhaps now you’ll learn to have more consideration for others,’ shouted the woman righteously. ‘And don’t think you can

treat us like the local peasants and frighten us with your pathetic death threats. We know you’re all mouth.’ She approached

the edge of the pool and peered at the pink shapes in the water. The corners of her mouth twitched upward. ‘And no trousers,’

she added before marching away, her supporters following in her wake.

Police Constable Ian Merryweather answered the call in his new patrol car. Suspected suicide in Stokeworthy churchyard. He

hoped it wasn’t messy. Only last week he’d been called to a farm where a man had put a shotgun in his mouth and pulled the

trigger: blood and brains everywhere. As he put his foot down and negotiated the narrow country lanes at considerable speed, he hoped this corpse had been considerate enough to swallow a

few sleeping pills before lying down in an orderly fashion.

It was twenty past midnight when he drew up at the rickety lychgate that separated the churchyard from the road. A small group

of people milled around the gate: late Friday night drinkers on their way home from the Ring o’ Bells, Merryweather thought.

It was hard for the constabulary to enforce licensing hours in these scattered villages. He stepped out of his patrol car,

donned his cap and drew himself up to his full height as the good, or not so good, citizens of Stokeworthy eyed him expectantly.

The group parted to reveal a pair of teenage girls sitting on the lychgate bench, sobbing into disintegrating tissues. They

were being comforted by a couple of overweight older women, presumably their mothers. Merryweather took charge of the situation.

‘Right, then. Can someone tell me what’s been going on?’ From the distraught state of the girls, Merryweather feared that

the message had been wrong: perhaps they had been indecently assaulted. He contemplated radioing for a WPC right away.

‘Go and have a look for yourself,’ said the plumper of the mothers defiantly. ‘Over there.’ She gestured impatiently with

her thumb.

Merryweather took a deep breath and set off down the church path.

It wasn’t long before he saw it. A couple of the male pub-goers had followed him tentatively up the path. He turned to address

them. ‘Hasn’t anyone thought to cut her down? She could still be alive.’ The men looked blank. The idea hadn’t occurred to

them. ‘Move back, now. Don’t just stand there gawking,’ he said with what he hoped sounded like authority.

He looked up at the figure hanging from the tree. It was a woman in a belted white mac. Her arms hung limply by her side,

puppet-like, and her discoloured face, tongue protruding, told that hers had not been a peaceful death. A metal ladder was

propped up against the tree: she must have jumped from it to her untimely death. Constable Merryweather climbed up a few rungs

and touched her wrist, feeling for a pulse. There was none. The body hadn’t yet begun to stiffen but it felt cool to the touch.

He descended the ladder and radioed for assistance, wondering whether to cut the body down for decency’s sake.

But something stopped him taking action. It was obviously suicide but, if by any chance it turned out to be less straight

forward than it looked, he had no wish to be hauled up before CID for destroying evidence. He’d leave that to someone else:

Merryweather was always a man to play safe. Besides, his back had been playing him up recently and hauling dead bodies around

might be the last straw.

Crowd control: that was the best use of his talents until help arrived. He noticed that the people by the lychgate had begun

to edge into the churchyard. ‘Come on, now. Move back. There’s nothing to see,’ he announced in time-honoured fashion. There

was nothing he could do for the poor cow who was dangling from the tree, but he could at least keep public order: that was

what he was paid for.

‘Who found her?’ he asked the assembled company, trying not to look at the hanging body which stood out white against the

darkness of the great yew tree.

‘I . . . er . . . we did,’ said one of the sobbing girls. ‘It was ’orrible.’

‘I’m sure it was, miss. We might need a statement from you. What’s your name, my luvver?’ he asked in true Devon fashion.

‘Jo . . . Joanne Talbot. And Leanne . . . she was with me and all.’

‘Leanne Matherley,’ said the other girl, barely audible.

Merryweather addressed the assembled group, growing by the minute as more villagers, some sporting dressing gowns, left their

houses to join in the excitement. ‘Does anyone know who the dead woman was?’

‘Aye,’ said one of the drinkers. ‘It’s her that works at the doctor’s. She lives in Worthy Lane . . . opposite them new holiday

cottages.’

It was with some relief that PC Merryweather’s sharp ears picked up the approaching sound of a police car siren drifting through

the night air. Reinforcements had arrived, with the police surgeon following close behind in his Range Rover.

He let them into the churchyard and resumed his crowd control duties, using his time and natural curiosity to find out what

he could about the dead woman and whether anyone had noticed if she’d been depressed recently. Apart from the fact that her

name was Pauline Brent, a nice enough woman who worked as receptionist for the local GP and kept herself to herself, he discovered

very little. She had lived in the village for about fifteen years and was still regarded as a newcomer.

After a few minutes Merryweather felt a hand on his shoulder: the large hand of Sergeant Dowling from Neston police station

who had arrived in the patrol car. ‘A word, Ian.’ Dowling drew the constable to one side away from curious village ears. ‘The

doc’s not happy. He thinks there’s something not quite right so he’s going to get the pathologist up here to have a look. Get the area taped off, will you. And take names and addresses . . . just

in case.’

PC Ian Merryweather, glad that he’d not trampled all over the evidence, went about his duties with renewed enthusiasm.

Charles Stoke-Brown put the white carrier bag on the floor and fumbled for his key.

He picked the bag up, pushed at the studio door and flicked on the light, a bare bulb in the centre of the ceiling. Something

was wrong. He was an artist, not a tidy man, but he knew that the mess in the long, low studio was not all of his making.

Drawers had been opened; the mattress on the unmade double bed in the corner had been tipped over; paintings that had been

piled against the walls now carpeted the bare wooden floor. A small window pane had been broken to enable the intruder to

open the larger window and climb in. He had been burgled.

Charles ran to an open drawer and made a swift search. The photographs had gone. He could feel his face flush red: there was

no need to mention them to the police. He began to pick up the canvases from the floor and pile them against the walls, thinking

he’d better report the break-in, if only for the insurance. But as far as he could see, very little had been taken. He reached

inside the carrier bag he was still holding and drew out a small, framed sketch . . . at least they hadn’t got that; it had

been with him, safe.

He would tidy the studio and get the window mended in the morning, but at that moment he felt like walking. Walking to forget:

to erase the evening’s events from his mind. He would call the police later.

He grabbed the door key and went out again into the misty night air. There were police car sirens – quite close. Or was it

an ambulance?

He walked on, away from his home in the converted water mill at the far end of the village. Normally when he walked after

midnight he had the place to himself, with only owls, screeching foxes and the occasional gaggle of drunk or drugged-up local

teenagers to spoil the peace of the sleeping village. Or, more recently, those new people at Worthy Court, with their loud

music and weekend parties. But tonight was different.

As he neared the church he spotted the small crowd of people, some seemingly in their nightclothes, standing by the lychgate,

deep in speculative conversation. Then he saw the police cars.

He turned, his heart pounding, and began to hurry back towards the mill, moths fluttering at his face, their ghostly wings

illuminated by the full moon. A bat swooped from a tree, bringing him to a sudden halt.

Then, out of the bushes beside the narrow road, two shapes staggered towards him. They were young, about seventeen; one dark,

one fair. Their faces bore the marks of acne and youthful bravado . . . and something else. Wherever these boys’ minds were,

they weren’t in a small village in South Devon on a warm June night. Their eyes were distant, hardly registering Charles.

Drunk, thought Charles: the victims of a Friday night session on cans of strong lager behind the village hall, or . . .

His worst suspicions were confirmed when the smaller of the pair collapsed on the road. The other looked at him, puzzled,

with none of the unfocused bonhomie of the overindulgent drinker. He bent down to address his supine friend. ‘Hey, Lee . .

. there’s a man . . . he ain’t got no face . . .’ The boy’s speech was decidedly local and horribly slurred. The lad on the floor giggled but made no attempt

to get up.

Charles moved forward, intending to sidle past. ‘Don’t go. Come and see the angel . . . in the trees . . .’ The taller lad,

his faded T-shirt covered in something unpleasant, approached Charles with outstretched arms. Charles took the opportunity

to escape.

He walked swiftly off down the road, trying to put the encounter from his mind. He had come to Stokeworthy to avoid such things;

to paint, to return to the simplicity and peace of country life. As a police patrol car flashed past, Charles flattened himself

against the hedgerow. The last person Charles wanted to meet at that moment was a representative of the local police force.

Detective Inspector Gerry Heffernan was fast asleep when the telephone by his bed shattered the peace of the room. He always

slept well on summer nights, when he could leave his window wide open to let in the sound of the water lapping against the

quayside outside his front door. But the telephone meant that his sweet, nautical dreams were to be short-lived. He picked

up the receiver and grunted a sleepy greeting, only to be informed by the offensively awake constable on the other end of

the line that he was needed at Stokeworthy. Dr Bowman, the pathologist, had been called, he was told in awed tones, and it

might be a case of murder.

‘Might be? Doesn’t he know?’ he asked, indignant.

‘That’s what he said, sir. Might be. He said to call you, sir,’ the constable added, apologetic.

‘Murder,’ Heffernan muttered to himself as he pulled his trousers on. Then he picked up the phone and dialled. When Wesley

Peterson answered, he could hear a crying baby in the background. ‘Sorry about this, Wes. We’re wanted. Suspected murder . . . Stokeworthy.’

As he waited for the sergeant to arrive, Heffernan gazed out of the window, watching the fishing boats, laden with lobster

pots, chug down the River Trad towards the sea, and wondering what kind of murder had been committed in a nice quiet village

like Stokeworthy.

1 March 1475

John Fleccer is amerced because he forcibly deprived Robert the minstrel of his lute and beat his son. Fined 6d.

Thomas de Monte, the stone carver, doth misorder himself with knocking at the doors and windows of Ralph de Neston in the

night and frightening them in their beds. The said Thomas did claim to the jury that he would speak with Ralph de Neston’s

daughter, Alice, to her father’s displeasure. Fined 2d.

From the Court Rolls of Stokeworthy Manor

‘Sorry about this, Wes,’ Heffernan said with some sincerity as he climbed into the passenger seat.

The young man at the wheel smiled. He was a good-looking man; his skin dark brown, his eyes warm and intelligent. ‘That’s

okay,’ he said. ‘Michael decided it was time for his feed anyway. He started to bawl just before the phone rang.’

‘That child must be psychic.’ Heffernan paused. ‘Murder. That’s all we flaming well need with the tourist season upon us. You’ve not had the pleasure of a tourist season

yet, have you, Wes? It’ll be a whole now experience for you.’

Wesley stared ahead, concentrating on negotiating the narrow lanes. He had been transferred to Trad-mouth from the Met the

previous September, and the changes to the district brought about by the influx of summer visitors were, as yet, a mystery

to him.

‘What kind of place is Stokeworthy, sir? Don’t think I’ve come across it yet.’

‘Just a village – church, pub, council houses, cottages. A lot of weekend places and holiday lets, you know the sort of thing.

And there’s a manor house . . . medieval, I’m told. It’s near Knot Creek, a little inlet off the Trad. I’ve put in there a

few times at high tide.’

‘You seem to know it well.’

‘Not really. Kathy used to like walking. We’d go all over the place in the old days. We walked from Stokeworthy church down

through the woods to the creek once.’ The inspector’s voice softened as it always did when he talked about his late wife,

whom he had met by a happy quirk of fate when, as first officer of a cargo vessel, he’d been winched off his ship by helicopter

suffering from appendicitis and taken to Tradmouth Hospital where he had fallen for Kathy, his nurse. After that he abandoned

his native Liverpool and joined the force in Tradmouth. Kathy had died three years ago and Wesley, a perceptive man, knew

that he missed her very much, although he never put his grief into words: that wasn’t Heffernan’s way.

‘Is the manor house still lived in?’ The mention of a medieval manor had caught Wesley’s interest.

‘Some rich businessman bought it, I believe. No doubt well in with the Chief Constable, so don’t you go digging up the foundations.’

Wesley smiled. He was used to his boss making quips at the expense of his archaeology degree.

‘Anyway,’ Heffernan continued, ‘this murder’s probably a domestic. They usually are. Some man’s come in from the pub and found

his missus in the arms of the milkman . . . or vice versa in these days of equality.’

‘Looks like we’re here.’ Wesley, having followed the rural signposts carefully and avoided any unpleasant encounters with

agricultural vehicles on the narrow, unlit lanes, felt rather pleased with himself as he swept past a sign that informed him

that Stokeworthy welcomed careful drivers. He slowed down, looking for signs of life . . . or death.

They reached the ancient church at the heart of the village, where a few feeble streetlights glimmered, making little difference

to the inky darkness. Wesley slowed down almost to a halt when he spotted the flashing lights of two police patrol cars parked

near a large group of curious villagers who were milling around the moonlit lychgate that led to the churchyard.

‘Quite a crowd . . . no doubt here for the free entertainment,’ said Wesley philosophically as he parked the car.

‘Like a ruddy public hanging. They can’t all be witnesses. Tell the local lads to take names and addresses and pack ’em off

to bed, will you . . . preferably their own.’

Wesley got out of the car and showed his warrant card to PC Merryweather, who had been eyeing him with considerable suspicion.

Heffernan remained in the passenger seat, weighing up the situation.

‘I’ve taken names and addresses,’ said Merryweather with some indignation when Wesley passed on the inspector’s orders. ‘And I was just going to get this lot off home. I suppose

you’ll want to talk to the girls who found her. They’re over there with their mams.’

‘Fine. Thanks.’ Wesley attempted a smile, fearing that he’d already put at least one local back up.

Merryweather turned away. He had heard they’d got some black graduate whizz kid from the Met down at Tradmouth CID. He wondered

how this paragon of modern policing got on with Gerry Heffernan: perhaps the blunt Scouser would be enough to send the whizz

kid scurrying back to London where he belonged . . . which might not be a bad thing.

When the crowd began to drift off to their beds, Heffernan emerged, bear-like, from the car. To Merryweather’s disappointment

he gave Wesley a friendly slap on the back. ‘Right, Wes, where’s this here body? Let’s go and take a look, shall we?’

Wesley nodded. ‘It’s near the church. Two girls found the body of a middle-aged woman hanging from a yew tree. She’s been

cut down now, so I’m told. The girls who found her are over there. Do you want to talk to them?’

Heffernan thought for a moment and looked at his watch. ‘Nah. Let ’em get home and get some beauty sleep. We’ll have a word

in the morning.’

As Wesley arranged this, Heffernan passed under the lychgate and walked slowly up the path to the church. It was a long, winding

path, flanked on either side by tombs of varying shapes and sizes: flat tabl. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...