- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

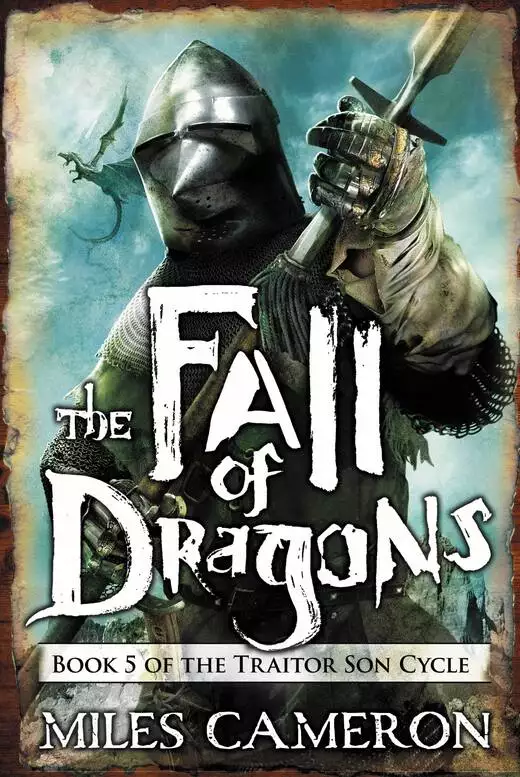

Synopsis

The Red Knight's final battle lies ahead . . . but there's a whole war still to fight first.

He began with a small company, fighting the dangerous semi-mythical creatures which threatened villages, nunneries and cities. But as his power - and his forces - grew, so the power of the enemy he stood against became ever more clear. Not the power of men . . . but that of gods, with thousands of mortal allies.

Never has strategy been more important, and this war will end where it started: at Lissen Carak. But to get there means not one battle, but many - to take out the seven armies which stand against them and force Ash, the huge black dragon, to finally take to the field himself . . .

Release date: October 31, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 688

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Fall of Dragons

Miles Cameron

The sun was setting in a sky of gold, and the bronze light suffused everything, gilding the endless forest, bronzing the stones left by ancient glaciers, and burning on the spear-tips of the retreating Army of the Alliance. The golden light set fire to the bright hair of the oldest irks and kindled the fur of the Golden Bears. It smoothed faces deeply creased by terror and fatigue.

Bill Redmede looked down the long column of weary men and a few women and then looked at the strange golden sky.

“Rain?” he asked John Clothyard, who was now, to all intents, his lieutenant. Nat Tyler had left him; killed the king, or so some men said. Ricar Fitzalan had gone east to serve with Aneas Muriens as battle comrades or lovers or both. The Jarsay-born Fitzalan had been a fine leader and the best second a commander could ask for, and Redmede missed him. He missed Tyler, too. Instead he had Grey Cat, who tended to wander off into the woods, and Clothyard, who was solid and dull.

Clothyard was a broad man of middle height, and his looks weren’t helped by a four-day growth of beard.

“Rain,” he responded.

Redmede was so far past exhaustion that he didn’t have to think much about his actions. He put a hand on the bow slung over his shoulder in a linen bag and trotted back along his Jacks. “Rain!” he yelled. “Put your bowstrings in your shirts.”

“Who the fuck are you? My father?” muttered one Jack. In a single summer of constant fighting, the Jacks had dispensed with camaraderie and turned instead to discipline. Some resented it.

“I never wanted to be a goddamned forester,” said another voice. This was directed at the grim reality that royal foresters, the king’s law in the woods, were the traditional enemies of the Jacks, broken men and outlaws, and now they marched together, the last Jack only two paces in front of the first forester. Not one forester or Jack was so dense as to miss the grim irony that in the eyes of the world’s powers, they were exactly the same: superb woodsmen and rangers. Ser Gavin, the army’s nominal commander, had put the two bands together with some hundreds of irk knights mounted on forest elk and irk ponies, an armoured cavalry that could glide through heavy woods with the agility of wild deer. Together, they were a match for almost any forest foe.

“Keep your bowstrings dry,” Redmede repeated as he trotted down the column. Not everyone was surly; Stern Rachel gave him half a grin, but she was mad as a felter and loved war; Garth No Toes hummed to himself as he flourished a little beeswaxed bag.

Most of these men and women had survived the rout after Lissen Carak; had fought at Gilson’s Hole; had marched west again to face Ash and his million monsters. They knew how to survive a little rain.

He told them anyway. Tired people make mistakes.

He forced himself up the rise he’d just descended, looking for the blank exhaustion that was like a sickness; looking for signs of people who hadn’t drunk enough water. His thighs burned, but it was these displays of routine prowess that marked him out, and he knew it.

He reached the top just as Long Peter and Gwillam Stare came over the crest, glanced back into the hell of Ash’s army, and shook their heads.

“We fightin’ agin?” Stare asked.

Redmede shrugged.

“Only have nine shafts,” Stare said.

Long Peter didn’t speak much at the best of times. He kept walking.

“I hear you,” Redmede said.

“Meaning we might fight,” Stare asked.

“Meaning I don’t know a goddamned thing,” Redmede said.

He could see his brother trudging up the hill. The same irony that made the two bodies of men and their decades of enmity irrelevant in the current crisis was sharpened by the two Redmede brothers: Bill, the leader of a rebellion against royal authority, and Harald, his older brother, who had risen to command the foresters. That maturity had brought each to a better understanding of the other’s position might have been the reason that the two bodies could cooperate at all.

“Harald?” Bill said.

“Bill.” Harald nodded. Both Redmedes were tall and ruddy-haired and rough-hewed; where Bill wore the stained, loose off-white wool cote of the Jacks, his brother wore a sharply tailored jupon in the forester’s forest green, although he carried his hat in one hand like a beggar. He stopped at the crest, and his weary men shuffled past; Bill was starting to know their names, and John Hand, tall and strong as an old oak, sporting a knightly beard and mustache, was Harald Redmede’s best officer. He grunted a greeting and kept going, glancing back at the rising tide of bogglins behind them as almost every man and woman did on reaching the crest.

“I heard a rumour we won a big fight in Etrusca,” Harald said. “Heard it this morning from Ser Gregario.”

“I heard that there’s a thousand dead of the plague in Harndon,” Bill said.

“Aye, or three times that.” Harald Redmede leaned on his bow staff.

The first drops of rain fell from the golden sky.

“We winning or losing?” Bill asked his brother.

“Losing,” Harald said. He held his hat—full of berries—out to his brother, who took a handful and ate them, seeds and all; black raspberries, fresh picked.

Bill nodded. “Well, that makes me feel better,” he said.

Both of them looked down the ridge they’d just abandoned without a fight to the enemy, who were already crowding the ground below them; a flood of bogglins, so many that the ground seemed to move with chitonous lava.

The irk knights were the last in the column. Even their magnificent animals seemed dejected; stags with racks of antlers that were themselves weapons walked with their heads down, and their riders walked beside them.

“We’re fucking doomed,” Harald muttered. “Sweet Jesu, I’ll end up being taken for a Jack if I keep on like this.”

Bill Redmede shrugged. “I trust Tapio,” he said. “He’ll see us right.” He didn’t say, The happiest hours of my life were spent in N’gara and I’ll fight for it. N’gara was just a few leagues away, and Ash’s entire autumn campaign seemed bent on taking it.

Harald smiled without mirth. “My brother the fuckin’ Jack believes an elf will save us, and I think that the queen’s commander is a lack-wit. Well played, my brother. We can change off; I’ll take the Jacks, you take the foresters.”

Bill shrugged. “You always was contrary, Harald.” He looked at the looming sky. Thoughtfully he said, “We need shafts.”

“As do we. Best hope the mighty Ser Gavin knows it, too.” Harald shook his head. “If’n we stand and talk any longer, we’ll be eaten alive by bugs.”

The two men turned, and began to trot along to catch their people, who were retreating into the strange, wet, golden evening.

The Vale of Dykesdale—Ser Gavin Muriens

Ser Gavin Muriens sat heavily on his destrier, feet out of his stirrups to ease his back, great helm and gauntlets on his squire’s saddle-bow, idly picking something wet and grisly out of the spike of his little axe.

He was looking out over the valley that the irks called Dykesdale, watching his vanguard (in this case acting as his rear guard) toil down the far ridge like a line of ants slipping along to a food source.

At his feet, the Vale of Dykesdale stretched for some miles below a long ridge whose top was dominated by old maple and beech trees in the full colour of late summer growth. Many of them had lost their tops, as if a winter ice-storm had swept along the ridge, and there were gaps where men and irks had hewed away patches of wood.

Below, in Dykesdale itself, a crisscross of streams and beaver dams funneled all approaches to the ridge into two main routes: the Dyke, an ancient dam built by long-vanished Giant Beavers, and the Causeway, a stone and earth tribute to the Empress Livia’s failed attempt to wrest N’gara from the irks fifteen hundred years before.

Ser Gavin had chosen it as the ideal battlefield, with Tapio, the Faery Knight, and Mogon, Duchess of the West, and Kerak, her mage, after the two defeats farther west. They had stood here, on the same bare, round crest that the Outwallers called “The Serpent’s Rest,” and looked out over the magnificent country.

“It’s like an impregnable fortress, built by nature,” Gavin had said.

Tapio smiled so that his fangs showed. “It isss an impregnable fortress, oh man. But it wasss built by my kind, to defeat all comersss.”

And Mogon had lowered her great crested head. “Armies founder here, as the wardens know all too well. But our enemy comes in numbers that this place has never withstood.”

“Aye.” Tapio nodded.

Lord Kerak smiled. “You see only defeat. But we have discussed this, Lords of the East. We have slowed him, and made him show us his real warriors, his broken wardens, his hastenoch, his trolls. All I ask is that we make him use his power. Harmodius and Morgon and I have … a surprise.”

“Will it work?” Ser Gavin asked.

“That depends on the depth of his arrogance and some fortune,” the scholar-daemon said. His heavily inlaid beak opened to reveal the purple-pink tongue within—the Warden’s equivalent of a smile.

Gavin was still coming to grips with the idea that the battlefield had been built. “It is all apurpose?” he asked, somewhat awed.

“Every tree, every branch,” Tapio said. “We didn’t build the ssstone caussseway.” His fangs showed. “We jussst left it asss a monument to the ssstupidity of men.”

Tonight, with the sun setting in a ball of fire beyond Ash’s legions, Tapio’s confidence seemed empty vanity. So did Kerak’s.

“We can’t fight many more times, and lose, without the whole will of this army snapping,” he said. “We need a win, even if it is fleeting.”

Kerak shook his head. “In this war there will be no victory, short of a miracle. Tomorrow, if we make a stand here, I will invite the opportunity for a miracle, but that is all I promise.”

Why did I want this job? Gavin said, but only inside his head. He’d already learned the key role of a commander in an alliance is to show relentless good humour and confidence.

So instead of speaking, he looked back west into the setting sun. The light was turning bronze from gold, but the strange metallic quality of the light was unchanged.

As far as Gavin could see, a carpet of moving creatures covered the earth, so that instead of grass, shrubs, and marsh, he could see only a vast blanket of enemies stretching to the horizon.

At his elbow, Tamsin’s voice was soft. “He has emptied every nest along the banks of the West River. Every bogglin. He has stolen the wills of millions of beings and he will use them as fodder for his vanity. Oh, how I hate him.”

“Tomorrow, I will use that vanity against him,” Kerak said.

“From your beak to God’s ear,” Ser Gregario said with his usual humour. “Let’s sleep. Unless you think they will come at us in the darkness.”

Tapio was still watching the endless carpet of foes. “If we lose here, we lose N’gara,” he said.

Tamsin kissed him. “Yes,” she agreed. “I am ready to lose it. Are you, my love?”

Tapio looked at Gavin. “We are all sssupposed to trussst your brother. Perhapsss I do. But even sssuppose that in the end, we triumph. Will there be anything left of my world?”

Very softly, Tamsin said, “No, my love.”

They all looked at her, for she was renowned as an astrologer and prophetess.

She shrugged. “When the gates open, the world changes. It has always been so. I need no wizardry to predict this.”

Gavin shook his head. “Let’s get some sleep,” he said. Far off to his right, the last of the column of rangers arrived at the foot of the great ridge to find rough shelters built of bark, and hot food. And bundles of arrows. There was fodder for man and beast, and fresh water. Everything that the hand of man and irk could do had been done.

“Tomorrow,” Tapio said. “I can feel it. I think we can stop him. My people have never been beaten here.”

Kerak bowed. “Tomorrow,” he said.

Mogon laughed. “In my youth, when this tree was young, I tried to make it up this ridge against you, Prince of irks, and my nest died like bogglins,” she said. “It is really quite pleasant to be on this side. Tomorrow we will win.”

Gavin nodded. “Tomorrow,” he said.

The sun rose somewhere, but over Dykesdale there was first fog, and then light rain, and the light grew very gradually.

Not a man or irk or bear or warden had slept damp, though, and every one had a hot breakfast. When Gavin had eaten his share of oatmeal porridge and bacon, he mounted a riding horse and rode the length of the ridge with Tapio and Ser Gregario. The highest summit, on the far right, was held by Mogon’s main battle; Exrech’s veteran bogglins, and Mogon’s hardened Saurian warriors, demons all, their inlaid beaks and engorged red-crests shining like myths come to life in the grey light of morning. In reserve, two hundred of the magnificent bears of the Adnacrags, the Long Dam Clan inured to war and many of their cousins and outbreeds, their golden fur darkened with damp. Many of them were sporting the heavy maille that the Harndon armourers had made for them over the summer, and almost every bear was wielding a heavy poleaxe as big as a barge pole in their paw-hands. A handful of Outwaller warriors stood with the bears; most of their kin were off in the east or fighting in the north against Orley, and the Sossag, once the mightiest of the Outwaller clans, were now protecting Mogon’s heartland from giant Rukh and yet more bogglins coming along the Inner Sea from the west.

In the center were the feudal hosts of Brogat and the northern Albin. There was Edward Daispainsay, Lord of Bain, commanding the dismounted knights in the center of the line although his wounds from Gilson’s Hole were not yet fully healed, and Lord Gregario with the mounted knights in reserve. The feudal levies were well armed with spears and armour; they had withstood days of attacks by bogglins without much loss, and they were more confident than most militia. They were beginning to be soldiers.

Tapio commanded the left of the line. There, the ridge was lowest and most vulnerable, and there were the Jacks and rangers; there also were the irk knights, and every irk regardless of gender who could be spared from N’gara. There, too, was Ser Ricar Fitzroy, with the knights of the northern Albin and Albinkirk, as well as fifty or so knights-errant from Jarsay, the Grand Seigneur Estaban du Born with another two hundred belted knights of Occitan, and there stood 1Exrech, his chitonous white armour spotless, at the head of his phalanx of spear-armed bogglins; they held the lowest ground, almost two thousand strong.

All told, they had almost eighteen thousand to face Ash’s million or so creatures. Or odds of roughly fifty to one. Gavin told his allies and his own more human officers that they were fighting for ancient N’gara, to show the irks that men and women could be trusted. But in his heart, Gavin was fighting because his brother had laid out a strategy and expected him to implement it, part of a plan so vast that Gavin could not imagine it would succeed. And yet, despite everything, he trusted his brother.

Gavin trotted his riding horse back up the central ride, the Serpent’s Hill, and dismounted. His page took his riding horse while his squire brought up his charger. A young man he’d never seen before handed him a cup of hippocras and he drank it while he considered the odds. They had to fight; that much had been made clear by his brother Gabriel all spring and summer. Every fight would bleed Ash, and only by fighting for every member of the alliance; the irks, the Jacks, the people of Alba and Morea; only by showing all of them that they could be defended would the alliance be preserved. This was not a war that could be won in an afternoon; Gilson’s Hole proved that. It was a war that might continue for generations.

In Gavin’s ear, Lord Kerak said, “Ready.”

While Gavin had reviewed his dispositions, the battle had begun. The tide of bogglins had rolled across the swamps and the dyke and causeway; had come forward like a seeping tide and splashed against the carefully sited earthen walls, the coppiced trees and “natural” stone features of the Dykesdale ridge.

The tide came in for an hour. Gavin watched, issuing no orders. There was nothing he could do but watch, but he stood as Ser Edward launched a counterattack that cleared the lower line of the center when the Brogat levies wavered. Tens of thousands of bogglins were used as filler by the creatures behind them, trampled to death and then walked over in the swamps.

The fog began to burn off. Off to the north, some low-level workings began to flay the waves of bogglins.

They broke. The tide flowed back; the waves receded into the swamps and ten thousand more bogglins drowned.

Gavin considered a second cup of hippocras and wondered what the hell his brother was doing, wherever he was.

Kerak spoke again from the aether. “Now he sets his will on the bogglins. Now they come again.”

This time the bogglins raced in, heedless of losses or terrain. They skittered over the carpet of their own dead and straight onto the spear points of the Brogat Levy. Below Gavin’s position, men and irks were dying again. His exhausted troops, manning the barriers and thickets, lofted clouds of arrows and stood their ground with sword and axe in hand. A hundred bogglins had fallen for every man; in some parts of the line, a thousand bogglins had fallen for every irk. But the second attack was pressed with more enthusiasm, and the drowned bodies in the swamp were now so thick that the next wave could cross dry-shod.

Off to the right, Mogon’s wardens and Golden Bears had lost less than a hand of their creatures, but even there every bear’s fur was matted and the wardens’ crests already deflated with fatigue. Along the first defence line on the ridge, the stacks of dead bogglins were already so high that the line had to be abandoned.

Out in the marshes, the dead were so thick that the course of the stream had been altered.

The Army of the Alliance was unrolling every scroll on war, and playing them out—ambushes, incendiaries, raids, dashing charges, destructive volleys.

Gavin looked out over the infinite fabric of his foes, and tried to wall off the rising tide of despair.

“Millions,” he said aloud. “But we are slaying mere thousands.”

Tapio smiled grimly, showing his fangs. “Millionsss are made of thousssandsss,” he said. “Hisss lossses are ssstaggering.”

Gavin shook his head. The tide had risen high; the sea of bogglins had swamped the first line entirely and were now facing the second, two hundred paces higher on the hillside. The sound was loud and constant; screams, war-cries, the despair of men wounded and eaten by bogglins, the equal despair of a bogglin whose carapace was penetrated; a week to die or a month, the creature was nonetheless already dead.

And then, like the changing of the light or the dissipating of the morning mist, the great assault failed. It did not fail suddenly; but inch by inch, bogglin by bogglin. Ash could take their minds and conquer their wills, but there came a point when flesh and blood conquered sorcery. Even bogglins had a scent sign for self-preservation.

The sky was turning blue overhead, and smell of bogglin blood was everywhere.

And so the tide went out for a second time.

“Blessed Saint Michael,” Gavin said. Across a nine-mile-wide battlefield, his people had held.

Far away to the west, almost lost in the mist, something rose into the air.

“Here he comesss,” Tapio said. “Pray to your godsss, or whatever else ssseemsss bessst to you, friendsss.” But Tapio was grinning. “We have hurt him.”

In all the other days of combat, Ash had never shown himself; not since Gilson’s Hole had his red-black form risen over a battlefield. His minions, most of them bogglins armed only with their natural claws, had flung themselves forward under compulsion, and Ash had not shown himself, nor, until two days before, had he committed a single wight, troll, or great hastenoch from the deep swamps of the north, not a single wyvern or irk.

These creatures were somewhere far off to the west; so far that no amount of sorcery or scouting could locate them. They were in reserve.

The black speck grew.

Gavin sighed. The real battle was about to begin. And his army was already so far beyond fatigue that the moment the tide of bogglins receded, the knights of the Brogat fell to their knees like monks witnessing a miracle.

The Vale of Dykesdale—Ash

Ash surveyed his foes with an impatience and annoyance that had become his constant state since being “embodied” in this, his chosen avatar. Annoyance, and fatigue. He had forgotten fatigue in the aethereal.

“Stupid children,” he said aloud.

He’d flung his almost limitless supply of animated chiton at their battle line in hopes that someone among his “foes” was bright enough to get the message and surrender, or skitter off into the woods. Time was growing short; the stars were moving, and his timetable was actually endangered. His “allies” in the sea required an enormous investment in will and time and immaterial power; but he needed them in place to wall off his competitors in Antica Terra.

That left him alone in Nova Terra; alone except for one rival of his own race and a host of smaller foes. Since none of these foes could possibly know what the game was, and how great the prize, except just possibly the old irk Tapio, he was annoyed that they even played at resisting him.

It is Lot, he told himself. Lot is using them as I use the bogglins, and to the same end. Stupid boy. He is far too late entering the game, and all his allies are too self-willed and too independent. But I still need to finish him, and quickly.

Ash had long since decided to have no allies at all—only slaves. It saved time and explanations. Even Thorn …

For a moment, the mighty Ash allowed himself to miss Thorn. But Thorn had not been loyal; Thorn had wanted too much of his own power. Like Orley.

Ash pondered the problems of metaphysical logistics; he had in his own right an enormous reservoir of power; his connection to the immaterium was nearly perfect, although never as perfect as it had been before he had made himself corporeal. And he had a strong connection to Thorn’s fortress at Lake-on-the-Mountain. Beneath it was one of the purest fountains of ops anywhere in the real, an out-welling that amounted to a tear in reality’s fabric; a tear someone had made in a war ten thousand years ago. He sucked at it like a baby on a teat, and used it to power the binding of millions of wills. Those bindings required two things he now had in short supply—his own will, and his time.

He hated time. He wasn’t used to it; it wasn’t “natural.” But he understood it well enough, and it ticked away with the movement of the stars only he could see, and pressed against him like an infinitely powerful phalanx of foes, and the onward press of time forced his talons.

And his tiny, contemptible foes had hurt him. He bore wounds on his immortal hide; signs of failure, signs that wrenched at his vanity as much as they caused physical pain. Pain. Another aspect of the material that he had forgotten.

Yet there was power—power to work his will—not through shallow intermediaries and foolish acolytes, but directly, as it had been in the beginning. He rose slowly over the battlefield on the cool autumn air and prepared a mighty working; something beyond the comprehension of most of the mortals below him. Not just a blow in the physical, but a message.

Surrender. Despair. Leave and let me have my way.

As a creature to whom the aethereal was a natural state, he merely willed and his will made manifest, and the world was affected.

But his thoughts, especially those of Lot, moved him and he twinned his consciousness so that a second Ash could, with only a slight diminution of his main effort, begin casting a delicate web, a tracery of aethereal strands to locate Lot wherever he moved in the real. And such was the dichotomy of Ash’s innermost mind that he didn’t admit to himself that he’d learned the technique from combatting the human mage, Harmodius. Even as he was aware that his failed assault on Desiderata had armed his enemies against him, and that he had, himself, betrayed Thorn, and not the other way around. A mighty mind has many holes and many traps and many concealments.

And self-knowledge had never been Ash’s strongest trait.

Instead, Ash balanced his expenditure on his Eeeague allies, strengthened the bonds that held the Orley and his creatures to his will, caressed the winds of scent and power that made a million bogglins his slaves, and relished the unfolding of a human betrayal he had motivated in the south, where, despite his own contempt for all men, Ash sought to destroy the magister Harmodius before he could reunite with his other allies. Because Harmodius was a foe. As was the human Morgon; so much potential there, but duped into the pit of Antica Terra. Let the mighty Morgon face Ash’s foes. That was a delicious victory. Perhaps he would defeat the elusive shadow; Ash allowed himself to laugh aloud. Or shadow would defeat him. Or rebel.

Shadow, rebel, will, Lot. Ash had played them all; all the rivals who mattered. Of them, he only feared the will.

Ash thought all these things and a hundred more while simultaneously plotting and commanding both his physical and his sorcerous assaults on the immediate battlefield. The bogglins flowed forward to their necessary deaths and his real troops, the troops he would need for the true contest when the gates aligned, came from their staging areas and began to move to the battlefield. With a beautiful economy that won Ash a bit of grudging self-admiration, he used the energy of the deaths of his first bogglins to power the Wyrm’s way working that moved a whole century of black-stone cave trolls straight into the center of the enemy, wreaking havoc. He’d never shown this tactic before; the result was immediate and spectacular, as a generation of Brogat knights were winnowed like ripe wheat.

But they died where they stood, and a dozen of his precious tolls became splintered rock.

What annoyed Ash most was this constant waste of resources. His were enormous but limited; his time was running like blood from a gaping wound, and his awareness of time was like pain; so very different from the way time molded itself when he had been outside it. He had things to do, and fighting bloody Tapio for this useless ridge was annoying. Annoying was the perfect word.

It was time to use his powers, because he was in a hurry and his beautiful trolls were dying.

Gavin watched the gradual defeat of his center with weary fear. In his ears, the two available great sorcerers and dozens of Morean and Irkish and Alban mages conversed rapidly, and he ignored them, watching instead as Ser Edward Daispainsay pounded a troll to the ground with a set of flawless strokes of his great hammer and then led another countercharge; farther north along the ridge, Ser Gregario, Lord Weyland, charged into the flank of the trolls with the mounted chivalry of the Albin, and the trolls were annihilated. But the damage was done; the whole second line would be lost, because subtle tactics were of no use against a million bogglins.

“Christ, he almost broke us in one assault!” Gavin said. “Where did the trolls come from?”

At his side, Tapio shrugged. “He hasss begun to ussse hisss actual army,” he said. “He moved the trollsss by sssorcssery.” He sounded smug. “Thisss tellsss me he mussst hurry,” Tapio added.

Gavin took a deep breath and wished his brother were there. “I hope you are right.”

“Here he comes,” Kerak said in his ear.

“He’s casting,” said Master Nikos, the former master grammarian of the university. He sounded satisfied.

“Now we will see something,” Kerak said.

Miles away and high above the battlefield, Ash detected the emanations of a dozen casters in the aethereal. Even as he knit his heavy magic, a massive working even for him, he lashed out against all twelve in a single pulse like a leven bolt the colour of dried blood that left patterns in the cloudless sky.

Tamsin hummed to herself as the brown bolts rolled across the sky. Her emanations were all constructs; in fact, they were reflector-beacons for actual casters located elsewhere. Before the lightning, almost as fast as thought, burst in pinpoint explosions of wood splinters and sulphur and raw ops, Tamsin had tracked each of them back to their point of origin and passed that vector to Kerak, who wove a diagram and passed it back—all in aethereal time.

As the sound of the explosions rolled along Dykesdale, Lord Kerak and the choir of mages of the allied army cast.

Even as they cast, Ash recognized both their method of observation and their method of detection and reacted, shed any working that he no longer needed and protected himself so that their mighty attack detonated in empty air.

But he clung to his enormous working, reaching far out into the aether itself for the ancient stones that rode there, moving along the star paths beyond the ken of any alive in the world of Alba. In the nigh infinite lore stored in his huge brain, Ash knew that the hollow rocks had been made by the Rhank aeons before, in an attempt to evade the gat

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...