- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Aranthur is a student. He showed a little magical talent, is studying at the local academy, and is nothing particularly special. Others are smarter. Others are more talented. Others are quicker to pick up techniques. But none of them are with him when he breaks his journey home for the holidays in an inn. None of them step in to help when a young woman is thrown off a passing stage coach into the deep snow at the side of the road. And none of them are drawn into a fight to protect her.

One of the others might have realised she was manipulating him all along....

A powerful story about beginnings, coming of age and the way choosing to take one step towards violence can lead to a slippery and dangerous slope, this is an accomplished fantasy series driven by strong characters and fast-paced action.

PLEASE NOTE: When you purchase this title, the accompanying PDF will be available in your Audible Library along with the audio.

Release date: December 10, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

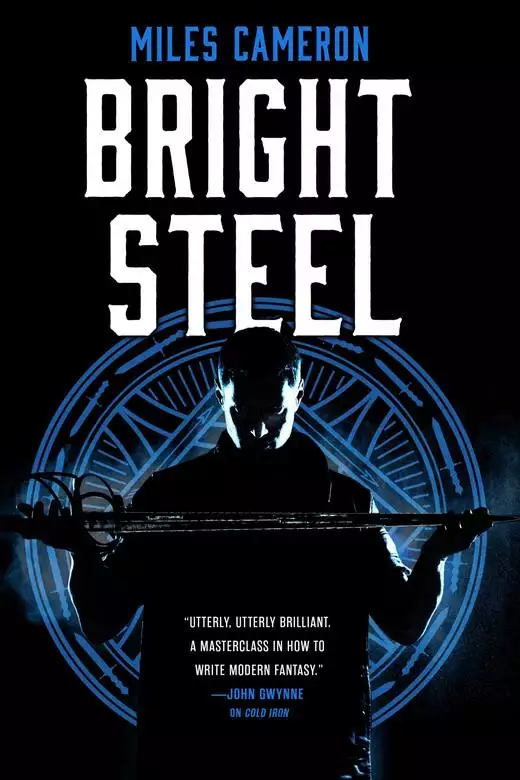

Bright Steel

Miles Cameron

He also understood, better than most of his peers, how vital it was that they hang on. He knew how badly their Master had been defeated, first in Armea and then at Antioke; how the timetable had nearly been ruined. He knew, because he was an initiate of the first order, how vital it was that the Emperor be killed; and how essential it was that the Sultan Bey be toppled. Out on the high seas, the Imperial fleet was turning the tables on the pirates; at Antioke, another army sent into action by the Master was being ground to bloody pulp by that witch, Tribane.

Djinar knew these things like articles of faith. He also knew that Verit Roaris was no longer himself; that his mortal frame had been seized by the Master because the man would not obey. Djinar knew it, and it filled him with fear, because he, too, had his own devices and desires, and he feared their discovery.

Disagreeing with the creature inhabiting Roaris’ body had been the stupidest thing he’d ever done.

Except that he was right. The new Disciple was not a native of the Empire; he could no more imagine the politics of the City than peasants tilling the fields could. He was making mistakes…

These are foolish, dangerous thoughts.

Fear kept him strong and alert, or so he told himself. And the mission to the Disciple of Ulama gave him a chance to show his worth, so that his moment of insubordination might be forgotten.

He hired a fishing boat to make the trip across the strait, and the fisherman complained of the change in tides since the emergence of the Dark Forge, the huge rift in the heavens and in the shell of reality that signified the changes to come. Djinar, as an initiate of the Pure, knew a great deal about the Dark Forge, but he hadn’t known that it was affecting the currents.

He listened until he grew bored of the fisherman’s ignorance of anything not relating to fish.

“Enough,” Djinar snapped at the end of his patience. “I hired you to sail, not to talk.”

The fisherman fell into a surly silence, but his efforts drove the little boat through the water, and although it took more than four hours, eventually he furled the sail, took to his oars, and brought them close in to the far shore where the reverse current ran, so that they seemed to float against the tide running in from the great sea visible under the rising sun, a sun which also gilded the prayer towers of the Sultan Bey’s palace and the majestic Temple of Light that dominated the heights of Megara to their right. Beneath the Temple of Light, the morning sun flashed on the Crystal Palace.

“A remarkable piece of vulgarity,” Djinar said aloud, on seeing its great windows.

The fisherman landed them on the beach at the edge of the immense wharf that dominated the Ulama waterfront. Built to accommodate the largest Attian and Megaran ships, it towered almost forty feet above the water, with slum streets concealed beneath the wooden wharves where Ulama’s poorest denizens lived and died.

The beach ran straight up to the rows of shacks, built in safety as the Sea of Sud tide never rose more than a foot except in extreme circumstances. Djinar cursed, but after he paid the fisherman he stepped over the side into the shallow water and waded up the beach past a man dying of bone plague.

“Disgusting,” he said, glancing at the dying man.

He made his way through the flotsam of the city, trying not to touch them, as if their poverty was a contagion that could infect him. He pulled on gloves and a Byzas aristocrat’s mask, and finally found a set of steps leading up out of the slums. He took them the way a drowning man might grab at a floating oar.

But at the top of the shallow wooden steps, he found himself almost across from the so-called Pantheon; the oldest temple in Ulama. He walked north as he’d been ordered, looking for the red chalk mark that would tell him all was well, and he found it, to his own satisfaction, brushed lightly across the belly of Potnia just outside the temple.

He reached up with false piety to touch the mark, her marble belly worn smooth by the thousands of pilgrims who had passed this way. The Master taught that all the gods were false; that there was no god but one’s self. But he encouraged outward signs of piety, because mimicry makes good camouflage.

He turned east and began to climb the high ridge that ran through the town.

He was crossing a tiny square, the dawn now a fully realised day, the sun rising in showy splendour over the snow-capped mountains of central Atti, when the footpads struck. There were three of them, wielding iron bars stolen from a construction site—crude but fearsome weapons.

Djinar was not much of a magos. Family connections had ensured he received the very best education at the Studion, but he lacked the connection to the sources of power which would allow him to cast complex occulta. All the same, he froze one attacker with a weak but well-formed command to the other man’s nervous system and he fell like a toppled statue as Djinar got his long rapier clear of its scabbard.

He offered the slim weapon to one of the two remaining footpads, waving the blade at the man until he batted at it with his iron bar, hoping to break the tongue of steel.

Djinar slipped his blade under the heavy blow and stabbed the man in the throat, the needle point punching through his neck even as the point grated on his spine. As the man’s knees buckled in death, Djinar raised his wrist and stepped back as if bowing to a dance partner, which, in a way, he was. The corpse fell off his lowered point.

“Your turn,” Djinar said.

The remaining man trembled with indecision; the sort of low person—as the Master taught—who turned to crime from inner weakness. Djinar thought he might be doing the man a favour in killing him; even with the length of a blue-white blade shimmering through the sticky blood of his friend in front of his face, the criminal couldn’t decide whether to attack or run.

Djinar tapped the bar with his blade, a sharp snap that forced the bandit to move. He raised the bar, his eyes wide with fear.

Quick as a cat, Djinar thrust through one wrist and turned his own, so that the slim blade severed the tendons of the other man’s hand.

He screamed and dropped the iron bar.

Like a snake, Djinar struck again, withdrawing the blade and stabbing through his body, and then, as he folded forward, through one eye. The blade came out of the back of the man’s skull with a pop.

“Goodbye,” Djinar said. “I suspect no one will mourn you.”

He stepped back and saluted his two fallen adversaries with an ironic flick of his blade that sent drops of blood flying through the morning air. He started to wipe his blade on a dead man’s burnoose, and then shook his head.

“Oh dear,” he said.

He walked over to the man whose limbs he’d frozen and smiled, meeting the man’s open eyes.

“I wonder if you can break my lock on you,” he mused.

He put the point of his rapier against the man’s neck under his chin and pushed very slowly, and so discovered his puissance was strong enough that the man’s life ended before he could break it. Djinar pushed the blade in very slowly, and then withdrew it.

“I wonder what it is like,” he asked the morning air. “Death.”

He cleaned his blade, and sheathed it in time to pass two veiled women going to the well. He bade them good morning, and smiled when one started to scream.

At the top of the apparently endless steps, he bought a cup of water from a water seller and savoured it, then walked away from the Sultan Bey’s magnificent walls and headed south, as he’d been ordered. He found the signs he expected, marks low to the ground in orange chalk, and he followed them through a maze of alleys between the high garden walls and the homes of the very rich. Eventually, when the sun was bright in the sky, he found the gate he sought: yellow with red trim, and a crouching lion in gold. He knocked, and a well-dressed gardener admitted him and took his name.

It can’t be this easy, he thought.

But it was. In moments he was summoned, and he climbed to the exedra, the long balcony of a summer palace. He could see through the windows to the apartments within; a dozen rooms for women, and then a long hall which he was led into. It was richly hung with silk carpets and a man sat on a dais, cross-legged on pillows with a naked sword across his lap. There were servants along the walls and a courtier or two, or perhaps they were more valued servants, leaning against the marble pillars that supported the roof over the nave of the hall.

Djinar bowed.

The man on the dais inclined his head.

“My lord, I bring you…”

Djinar looked up and saw the deadliest of his enemies standing in the shadows behind the dais. His hand went to his sword.

“Hold,” the lord of the hall said in accented Byzas. “He is no threat.”

“No threat?” Djinar asked. “He is our greatest foe.”

The lord smiled. “Look!. The serpent has no fangs.”

He waved at the figure behind the dais, and the man didn’t even blink.

“Gods,” Djinar breathed, fascinated. “We heard he was dead!”

The lord had a good-natured laugh, a fatherly one, and he laughed it.

“He very much wishes he was dead. Instead, he will serve me forever.”

Djinar noted that the Attian lord said “me” and not “the Master.”

“I heard that your attack on the Sultan Bey…”

Djinar met the man’s eyes and hesitated. His laugh was so at odds with his eyes that the words died in Djinar’s throat.

“It was unsuccessful,” the lord admitted. “This busybody made too much trouble.” He laughed again. “He will have to serve me for many years to balance the chaos he created in one hour.” The lord shrugged. “Never mind. You have a message for me, syr?”

“From the Disciple of Megara,” Djinar said, taking a sealed parchment cylinder from his bag.

“Even here, in my own house, you should not say such a thing,” the lord counselled. He broke the seal with his thumb, and began to read.

The sword across his lap moved. It almost seemed to crawl, or writhe like a snake, and Djinar flinched.

Tell me, a thin voice said.

It was like the ringing of tiny bells, or the vibration of a lute string, and the hair began to rise on the nape of Djinar’s neck, as if a haunting had crossed his path, or one of the fey.

“Interesting,” the lord said. His smile was now quite unfeigned. “Your master speaks highly of you.”

Djinar knew a moment of relief. “I’m sure I’m unworthy…” he began.

“Brilliant, ruthless, a true believer. Have you truly memorised Precepts of a Life of Power?”

“I have,” Djinar said proudly.

“But you have almost no talent for the Art,” the lord said.

Djinar sighed. “None.”

The lord smiled. “We live in wonderful times. The Old Ones are about to be released back into the world, and life will return to its natural rhythm. The weak shall be slaves, and the strong shall be like gods.” He raised his terrible eyes to Djinar. “Do you wish to have the powers of a great magos?” he asked, his voice mild.

“Of course!” Djinar said. “More than anything!”

“How splendid,” the lord said. “And how very convenient.”

He raised a hand, and the sword seemed to vibrate.

Later, it occurred to Djinar that the sword was laughing.

Four soldiers grabbed his enemy, still frozen in his grey robes—as if paralysed—behind the dais. They dragged him out into the light, and Djinar could see he’d been both defeated and subsequently tortured; the man’s nails were ripped from his fingers, and his mouth bled where his teeth had been ripped out.

“We broke him,” the lord said. “Not even Kurvenos, the great magos, the Lightbringer, could withstand us.” He laughed his happy laugh. “Now I have most of his secrets and, best of all, access to his power.”

Kurvenos stood unmoving. Only his eyes betrayed his terror, his horror, his despair.

“When I took him I knew he would make the most powerful Exalted ever created,” the lord said. “But I needed a pilot for this mighty warship, someone of impeccable belief… and lo, your Disciple sent you to me.”

“Me?” Djinar choked. “Exalted…”

“What is life but the lust for power?” the lord said, quoting from the Master’s book of maxims. “Prepare to have more power than you ever dreamt.”

Djinar screamed as he met Kurvenos’ eyes, and the soldier’s hands seized him.

Because, even as the lord and his acolytes began their chant, all Kurvenos’ wounded eyes held was pity.

Night over Megara; a night with both moons high in the sky, the Red Moon almost full, its tiny disc slightly imperfect, while the Greater Moon, the Huntress, was a mere sickle that looked as if its open arms were ready to catch the smaller ball.

It was the first night of a Mazdayaznian festival, the Dreamcatcher Festival, and the tavernas were open all along the waterfront, despite the presence of the Watch and the unofficial, but heavily armed, black and yellow liveried Yellowjackets of General Roaris’ household troops and political adherents. The General, who had taken to calling himself Lord Protector, had declared a curfew throughout the city while his household troops searched the city for “traitors.” Despite that, not just Easterners, but every young person in the City seemed to be sitting in a tavern, drinking. The Watch stood by, frowning; and the Yellowjackets patrolled the Northside beachfront and the Southside fondemento in small mobs.

On Southside, between the Great Canal and the Low Bridge, under the shadow of the Red Lion, a tall campanile of brick, stood the largest inn in the city; the Sunne in Splendour. It towered over the palaces to either side and was surrounded by a sprawl of stables and outbuildings, kitchens, guest houses, and a boat dock on the seaward side and another on the Great Canal. It was a warren of comfort and good cooking, ruled by Laskarina Boulbousa, who, according to the City tittle-tattle, had started life as a prostitute among the notorious Pirates of the Sud. Whatever the truth of the rumour, her Inn was a haven on the waterfront, she paid well, and had the best cooks and the best ostlers in the city. She knew the Emperor, General Roaris and General Tribane personally.

Rumour also said that there had once been a husband, who had owned the original inn in its perfect canal-front location. Whether he had, as rumour claimed, been poisoned and then drowned, or whether he’d died of natural causes, or whether there’d never been a Syr Boulbousos at all, the inn’s good reputation and its mistress’ slightly colourful reputation tended to keep trouble away. The inn had hundreds of rooms, a dozen commons and fifty snugs, allowing the Lions, Blacks, and Whites to all hold rival meetings in its environs and never come to blows—which was as well, because the proprietress paid her bouncers well, too. When trouble didn’t stay away, it was routinely punched in the head and thrown in the Great Canal, after which trouble, in most of its young forms, rarely returned.

The curfew was due to begin in a few minutes. A handsome man in a slashed doublet, black with gold lace revealing a black silk lining and a snowy white shirt that betrayed a slow leak of blood, leant out on a balcony above one of the inn’s courtyards. On careful examination one might see that beneath the fashionable cosmetics, the man’s face was bruised; and despite silver lines of Imoter occultae, his left hand was grotesquely swollen and had no fingernails.

“If he tries to enforce the curfew,” Tiy Drako said with something of his usual insouciance, although he slurred his words, “we might retake this city tonight, with no army but offended drunks.”

“You should be lying down,” Aranthur Timos said.

Autumn had come to the city, and Aranthur was wearing a fine wool doublet—not as elaborate as Drako’s, but finer than most, although it couldn’t conceal his emaciation. In his high boots and half-cloak he looked like a Byzas gentleman, if a very tall, thin one.

Behind him, Dahlia Tarkas sat on a divan rapidly copying anything Drako said into the flyleaf of a book of translated Safiri poetry.

“He should, but he’s a fool,” Dahlia said. “Drako, sit down. None of this will work if you faint.”

“I want to be out there,” Drako spat. He was missing two teeth, which gave his voice a sibilance it didn’t need. “Roaris is winning. Kurvenos is gone. Tribane is trapped at Antioke, and the Dark Forge widens every day.”

Aranthur came up beside his friend, slipped an arm around his waist, and took him to the divan and into Dahlia’s hands.

“I hate being cosseted,” Drako said.

“You’d hate being dead a lot more,” Dahlia said. “You have a touch of the Darkness, and honestly, only my puissance and Aranthur’s is keeping you on your feet. If I release the pain-blocker…”

“She’s not coming,” Drako said pettishly.

“She’ll come.” Aranthur glanced out into the night and pulled the curtains across the balcony windows. “And Tribane isn’t trapped. She’ll win.” He made himself smile. “Drako. We need to know everything about how you were taken. Everything you know about Kurvenos. Please… co-operate. You cannot go out there.”

Drako continued as if Aranthur had never spoken. “She needs food, powder, ball, replacements. Food. They all need food, from what you’ve said, and Roaris’ move was brilliant. Even if we topple him, the damage he’s done…”

Neither of the others disagreed.

I need food myself, Aranthur thought. He was hungry all the time.

“We should be planning a revolution,” Drako insisted.

Aranthur tugged at his growing beard; very fashionable among the Byzas and the Souliotes too.

“Tiy, you know they say that Imoters make the worst patients? Well, spies give the worst debriefings. We need to know what happened. I have a plan,” he said carefully. “And it doesn’t involve starting a revolution. In fact the last thing we need is a wave of violence in the City to rip the bandages off every old quarrel—faction fights, house fights…” He poured himself some wine from a bottle on the side table. “And the first to die would be the Easterners.” Aranthur put a hand on Drako’s shoulder, and put a little power into his pain-blocker; it already needed reinforcement. “Stop trying to plan. You need serious healing, and to tell us what happened.”

“Sophia,” Drako said. He glanced at Dhalia. “When did he become so—?”

“Skinny?” Dahlia asked.

“Arrogant,” Drako said.

“This from you?” Aranthur asked with a smile. “I made a plan, and I confess that I am now used to being the one to do it.”

The two men looked at each other for too long.

Dahlia brushed some breadcrumbs from her doublet.

“Are you going to fight? Because if you do, I’m leaving.”

“I’m struggling with the idea of Aranthur as the planner,” Drako said.

Dahlia raised an aristocratic eyebrow. “I don’t wish to take sides,” she said. “But he planned your rescue. And you needed to be rescued. So stop being so fucking high and mighty and tell us what in ten thousand icy hells happened.”

Drako winced and sat back suddenly, having encountered some half-Imotered ribs, and Aranthur put a hand to his neck to pass some more raw puissance into the healing.

Then he knelt in front of Drako. “Please?”

Drako blinked. “I hate telling the truth. And I hate failing, and this will be a truthful vomiting forth of fucking failure, fully fleshed in folly.” He smiled his old smile, and then shook his head. “I have a pile of reports on the money… the money Roaris must be spending on bribes to stop his castle of ice from melting. He’s living a gigantic lie—anything can topple him. And I know he’s paying bribes.”

He turned pale, and grunted, a hand across his abdomen, and Dahlia was there.

“Gods,” he muttered. “Where is she? I’m dying here…” He looked at the door.

Dahlia looked worried, put more power into her treatment, and frowned at Aranthur.

He shrugged. “I was making this up from the moment the boat landed us here,” he said. “I have to hope that our message got through.”

Drako scowled up at him. “Do you want to hear this or not? They grabbed Kurvenos in Atti. There was an attempt on the Sultan Bey—well-planned, but someone betrayed it to the Capitan-Bey and it turned into a bloodbath. An open street fight with heavy magic, hundreds of bystanders killed. Kurvenos went to see if he could help. A friend of his was badly wounded… probably another Lightbringer, and no, Kurvenos was no more open-mouthed with me then than with,—Sweet Sophia’s wisdom! Aphres’ flowery gate! Drax’s dick!”

He doubled over, the pain of internal haemorrhage leaking through their various attempts at healing. He continued to swear, his white shirt showing the blood very clearly.

They both did what they could, which was far too little.

“If I die,” Drako said suddenly. “Aphres. If I die, thanks for the rescue. I love you two. That’s no bullshit. I was going to die a nasty death and fuck, this is hard but it’s still better.” His head came up as the wave of pain passed. “They hit Kurvenos the moment he landed on the Ulama side, or that’s what I heard from my source, who was there. They got the Kaptan Bey; not last night but the night before last… No, it’s all too fucking confused now. Anyway, I met someone with access across the strait in Atti. I was going to mount a rescue. And the bastards had already started burning my people—two agents were already dead.” Drako looked up. “What are you going to do, Aranthur?”

“I really do have a plan,” he said. “Which is to do this with the minimum number of corpses. The stakes are very high, but this isn’t a one-time crisis. We need the Empire, and the City, to be stable, even comfortable. We need them to be solid—so I swear to you, if we turn taking Roaris down into a fight we’ll be playing straight into the Master’s hands.”

Drako shrugged. His eyes were too bright. “I know you’re right. Because he’ll play the factions—”

“Because we’ll be weaker. Because there will be more distrust. We can only win by being united. Divided, we’ll be crushed.”

Aranthur was so close to Drako’s left hand that he couldn’t help but look at it. It looked as if it had been beaten with an iron rod. The Imoter they’d found on the waterfront had done his best, but had described the hand as nothing but a bag of bones.

Drako leant back. “Pain-blocker is wearing off,” he said.

Aranthur shook his head like a reprimanded schoolboy.

“That shouldn’t be possible,” he said, and reinforced it.

It was like a problem in applied magical mathematics, with diminishing returns. The pain-blocker was going to fail, and his own hunger was growing like a mad thing eating at his vitals.

“Tell me what you plan,” Drako muttered.

There was a sound outside; footsteps on the stairs.

“For starters, I plan to land the Black Stone and move it to the Academy, where it will be safe. Where we can use it.” Aranthur was lying; he and Dahlia both knew it.

Dahlia’s head turned slowly, and her eyes met Aranthur’s with flat accusation, but there was, just then, a rhythmic knock at the door.

Aranthur leapt to his feet. In a moment, he had a small puffer in his hand. So did Dahlia. He moved to the door; she rose silently and went to the curtains, her left hand already burning with power, her shields ready to deploy.

Drako lolled on the divan.

Aranthur opened the door. Outside was a tall, cloaked figure in a plain mask and a long cloak—the brown cloak of a priest or priestess of Aploun.

“Cold Iron,” the woman said.

Aranthur bowed.

She swept into the room, took off her mask, and stood over Drako. She was neither young nor old, neither beautiful nor ugly; a plain, nondescript woman with brown hair.

“Who are you?” Aranthur asked. He was not quite pointing the puffer at her.

“Drako, you look like all the hells,” she said.

She leant over and put a hand on his forehead. He flinched, and a ring sparkled on her hand.

“Myr Benvenutu!” Aranthur said.

The woman turned, and gave Aranthur a slight smile.

“Very perceptive, Syr Timos.”

Even as she spoke, her guise dropped and she was revealed as the Master of Arts. She wore a silk gown under the brown cloak, beautifully cut. Aranthur had never really seen her as a woman before, or if he had, her form had been buried beneath her authority.

She smiled more widely. “I do go to parties,” she said.

Dahlia laughed and released her puissance and stepped out from behind the curtain, to be embraced by her mentor. Aranthur had never embraced the Master of Arts, so he stood in social confusion as she took his shoulders and kissed him on both cheeks.

“The man of the hour,” she said in her deep voice. “Your work on Drako is very good, but he has a high fever, he’s on the verge of going into shock and I think that’s a touch of the Darkness. I’ve prepared… friends. For this eventuality. Listen, we have to move quickly. I have reason to believe that Roaris is going to strike against the festival, and has plans to enforce the curfew. And I don’t have long—my daughter is pretending to be me a festival ball.”

Aranthur had known the Master of Arts for more than a year and had no idea she had a daughter.

To Drako, she said, “Can you walk?”

Drako nodded. “Of course.”

“Nonetheless,” she said, and there was a controlled burst of power. Aranthur noted that her ease of access to the Aulos was as good, or better, than Qna Liras’ or Kurvenos’.

“Sweet… Sophia’s…” Drako thought better of whatever he was going to say. But he rose carefully. “I’m healed!”

“Not even a little,” Benvenutu said. “I’m burning some of your youth to keep you on your feet. You have about ten minutes.”

“Oh, gods,” Drako said, as if the full extent of his injuries had just hit him.

“There’s a chair waiting at the base of the steps,” Benvenutu said. “The chairmen are friends. Get in, and trust them.”

Drako nodded slowly. “Where are you going?” he asked.

“The Academy,” Myr Benvenutu said. “I have to run it. Trust me. You will be well-hidden and taken care of.”

She ran a hand over Drako’s uninjured side, and suddenly he was guised exactly as she had been—as a tall woman with brown hair. She handed Drako her cloak and mask, and he bowed, winced, and steadied himself on the door frame.

“How will I find…?” he said.

The Master of Arts shook her head. “Tiy, you are badly hurt, inside and out. I’ve virtually cut your pain centres from your mind. It will take expert Imoters at least three weeks to heal you now. Just for once, do as you are told. Get in the chair and go.”

“Damn it,” Drako said, and then he was leaning against the door frame and Aranthur moved to catch him.

“Damn it,” he repeated.

Aranthur put an arm under his and helped him down the steep steps. There were people at the bottom; strangers, a dozen students. One had Yellowjacket livery over his arm. Another, a small woman, had seized his arm.

“You’re a fucking idiot if you think Roaris is a legitimate government,” she said.

The off-duty Yellowjacket tried to shake her off.

“That’s not an appropriate attitude,” he said, in a superior tone not calculated to win any argument. “I shouldn’t even be with you people—”

“I’ll tell you what’s not appropriate,” spat a young man. “Arresting everyone you disagree with. And I hear a whisper that Tribane didn’t lose in the East.”

“Treason,” the Yellowjacket said.

Another young man put a restraining hand on the Yellowjacket’s sword arm.

“Jace,” he said. “Not everything is treason. We’re out for a night of drinking, and you, my friend, are being an arse. When you fucking promised to keep your pious aristocratic mouth shut.”

Aranthur and Draco had reached the landing and Aranthur didn’t think this was the moment to hesitate; he could see the chair and the two men who carried it just past the students at the base of the steps.

“Fuck,” Drako said.

“Act drunk,” Aranthur said.

“Not a problem,” Drako hissed.

Aranthur began easing the brown-cloaked Drako down the last steps.

All of the students turned and looked at them. They were embarrassed to have been so loud, and curious, too, so they fell silent.

“Excuse me,” Aranthur said, in a deliberately pettish voice. “I need to get this priest to her chair. And gentles all, there is a curfew. Shouldn’t we all be going to our homes?”

The chair was sitting on its stretchers: a plain black box. Four very big chairmen stood by it, and all four wore cutlasses.

Most of the students moved from his path, but the biggest of them chuckled.

“No curfew in the Sunne in Splendour,” he said.

He was a young man used to getting his way; not particularly belligerent. Merely big.

Aranthur looked past him to the man who’d been called Jace.

“And you a member of the Special Watch,” he said, as if shocked. He go

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...