- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

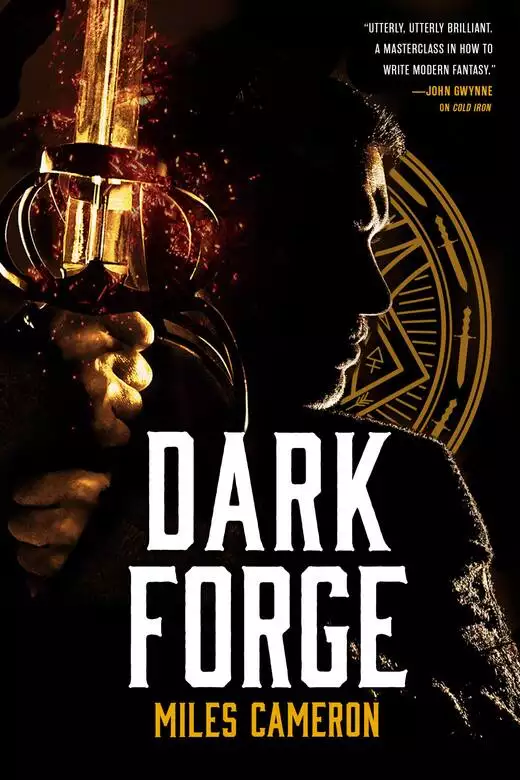

The next book in the Masters & Mages series that started with Cold Iron, from the master of fantasy Miles Cameron.

Only fools think war is simple or glorious.

On the magic-drenched battlefield, information is the lifeblood of victory, and Aranthur is about to discover that carrying messages, scouting the enemy, keeping his nerve, and passing on orders is more dangerous, and more essential, then an inexperienced soldier could imagine . . . especially when everything starts to go wrong.

Release date: September 17, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dark Forge

Miles Cameron

Aranthur’s eyes opened in darkness. He was, for a moment, completely disoriented, and then he knew; he was in a very small tent, and his hip was pressed against that of Prince Ansu, who was in the process of putting on breeches. His wriggling…

“I’m sorry,” Ansu said. “I can’t sleep.”

Aranthur rolled over, and clutched his borrowed wool blanket closer.

After a long moment in which he almost passed into sleep, he heard the faint but unmistakable sound of Dahlia…

Making love.

He sat up.

“Exactly,” Ansu said.

Aranthur failed to restrain a string of Darkness imagery.

“Black darkness; fucking thousand hells…”

“Let’s go for a walk,” Ansu said, equitably.

Hence you were putting on clothes, Aranthur thought.

It was odd to see Prince Ansu in Byzas clothes—almost a military uniform. He had leather breeches, an elaborate blue doublet and a small round hat with a turned-up brim.

“You’ll find that it’s almost dawn,” Ansu said. “Don’t imagine we’ll get back to sleep.”

Indeed, when Aranthur’s head poked out of the white wedge tent, he understood why it had been so easy to find his kit. Although true dawn was half an hour away, the sky had the iron grey cast of what the Nomadi troopers called “The Wolf’s Tail.”

The campfires at the end of the tent rows were crowded with Nomadi. Many were sharpening blades or clicking puffers. A few were eating. Some stared into fires.

Dekark Lemnas raised a steaming cup.

“So nice of you gentlemen to join us,” she called out.

The nomads laughed. But it was good-natured, and Ansu bowed elaborately. One Steppe veteran slapped his thigh.

“I thought I’d be the first one up,” Aranthur admitted.

Lemnas shook her head. “Day of battle,” she said. “Ever seen a battle?”

“Day before yesterday,” he said.

She barked a laugh. “That wasn’t even a skirmish, boso. Bah, perhaps a skirmish. Today, we will all get our feet wet.”

One of the regiment’s handful of Kipkak tribesmen spat.

“Battle is for fools.” Then he grinned. “I’m a fool.”

Their laughter had an edge to it.

“Good luck today, Syr Timos. I won’t pretend we wouldn’t all like to have your aspides, and Myr Tarkas too, with us. But I’ve heard—”

“I didn’t wake him.” Ansu turned. “We’re riding as couriers for the General.”

Aranthur nodded. “Well, I volunteered, way back in Megara.”

He began sorting his kit. He noted that old troopers like Vilna, the Kipkak, had everything laid out in one neat pile atop his saddle blanket: saddle; riding boots; sabre; two puffers; fusil; breastplate; saddle and headstall and coiled, polished leather tack.

Aranthur spent a nearly desperate half-hour finding all of his, spread over two tents and the horse lines. By the time he had Ariadne tacked up, he could hear Dahlia demanding quaveh and Sasan asking for some oil.

Vilna came by, his short-legged rolling gait announcing him even in the murk.

“Sword sharp?” he asked.

Aranthur bowed and handed over the old, heavy sword.

“Hmm,” Vilna grunted. “Huh.” He ran a thumb over the edge and raised an eyebrow. “Good sword. Old is good. Sharp like fuck.” He bowed, as if Aranthur was a little more of a human being than he’d expected. “Bridle but no saddle, eh? Saddle here. Long day. Life is horse. Keep horse fresh. Best, have six horse.”

“Thanks,” Aranthur managed.

He was fine, mostly, but every few minutes a new set of fears rose to choke him. His body would flood with a sense of danger; his hands would tremble.

It was exactly like his first duel. He had no idea what to expect, and that was the thing that made him afraid.

When Ansu was feeding his mount, Aranthur asked, “Have you seen a battle?”

Ansu laughed. “Syr Timos, I come from civilisation. We have law, and just rule, and hundreds of drakes to tell us when we err. We haven’t had a battle in two hundred years.”

Aranthur bridled at his friend’s smug superiority.

“But you fight duels,” he snapped.

Ansu shrugged. “Not as… frequently… as you Byzas.”

“I’m not Byzas,” Aranthur said.

“I misspoke. I will apologise—”

“Nah. I’m cursed snappish.”

Afraid, Aranthur almost said. Instead, he turned and embraced the Easterner, and felt the prince’s somewhat diffident return clasp.

“Hah, this is a good custom, and one hug is worth a great many words,” Ansu said. “My hands are shaking.”

“Mine too.” Aranthur admitted.

“Listen.”

Far off, in the direction of the enemy, there was a long roll, like the rise of summer thunder in the hills above Soulis.

It reached a crescendo and stopped.

And started again.

“By the Lady, what is that?” Aranthur asked.

Ansu made a face. “Our foes two days back had drums.”

Sasan came up with two feed bags.

“Morning, friends.”

Aranthur found it impossible to hate the Safian man, even when he had just been making love to Dahlia.

“Morning, Sasan. Are those drums?”

“Oh yes,” Sasan said, a trace of bitterness evident in his speech. “Every Beglerbeg has at least a pair of big drums, for signalling and for status. They’ll form in front of his tent every morning. The more powerful officers will have six or even ten drummers—big men, mounted on camels with a pair of big drums.”

A new drum storm began.

Sasan’s eyebrows went up.

“That’s a great many drums,” he admitted.

All along the cook lines, men and women were peering out east, where the sun was just cresting the rim of the world. The drums had a supernatural quality, and they rolled again, long and deep.

Aranthur shrugged to his friends.

“I’m ready,” he said. “I’m going to the General.”

Sasan was just tacking up two mounts and Ansu was still drinking chai.

“Go with the gods,” Ansu said. “I’m not in a hurry to do work, and that’s all she does.”

Aranthur nodded, and walked off across the camp, leading his horse. He walked to the head of his squadron street. He was not actually a member of the Imperial Nomadi, but his own militia regiment—the Second City Regiment, often called “The Tekne”—was in a different camp, and his officer was also a Nomadi officer…

The army was like a large, sprawling, complicated family.

“His” squadron was a street of fifty tents, twenty-five on either side, each holding two troopers and all their tack. At the head of his street was his centark’s pavilion, a fine silk tent with heraldic bearings.

Centark Equus stood in front of his tent, fully armed, with his light armour on. He smiled, Aranthur threw a barely competent salute, and Equus bowed with some irony.

“Good morning, Syr Timos,” he said.

“Good morning, syr,” Aranthur said, formally.

“Try not to put your head in the way of a cannonball, there’s a good chap.”

“I’m going to find the General.”

“Off you go, then.”

Equus went back to drinking his quaveh, his eyes on the eastern horizon.

Aranthur walked across the dry grass, trying to imagine that the cheerful Equus might be afraid. He saw no sign of it.

The General’s pavilion was in the exact centre of the Imperial camp. Her personal standard fluttered from the central pole, and her pavilion had three peaks and seemed as large as a palace. There were four sentries, all very alert, and behind her tent, an entire squadron of City Militia cavalry stood by their horses, armed and armoured, booted and spurred.

Even as Aranthur walked his horse across and through the camp, everything changed. The rumble of the enemy drums was drowned out by the sound of wheels and heavy horse tack, and a dozen great gonnes—more—rumbled past. Each great gonne had a bronze barrel twice the length of a man, or longer, the muzzles cast like fantastical monsters. Each gonne had a pair of lifting handles, made to look like leaping, swimming dolphins, cast so well that they almost seemed alive in the red light of morning. Each gonne had the touch mark of the casting master, and the coat of arms of the donor, the noble or merchant who had gifted the Imperial Arsenal with the cost of a great gonne. Their carriages were like heavy farm wagons, with wheels as tall as Aranthur’s head, bound in iron. All the carriages were painted sky-blue, and some had iconography painted on the gonne chest between the trails. Dragons and drakes predominated, but one heavy piece had the Lady rising from the waves, and another had Coryn the Thunderer pointing his war hammer.

Each gonne had an attendant ammunition wagon, and the gonne and wagon each had six horses in draught and forty men and women to serve the bronze monsters. The train rolled past Aranthur on the dry grass, raising dust even so early in the day. He had to slip between one team and another, taking his life in his hands before battle was even joined, because the drivers were not going to stop their charges for a mere man.

Behind the line of gonnes, companies and banners of infantry were forming on the grass strip that ran down the centre of the camp. It looked as if the whole population of Megara had been transported to Armea. There were thousands of men and women in each stand of pikes and arquebuses. The line seemed to extend into the dust at the edge of the world.

He saw people he knew—a wheelwright, an apprentice leather-worker, a tall, foppish man with whom he’d fenced. And then he saw Srinan, at the head of a troop of jingling City cavalry. The nobleman saluted with his sword.

“Morning, Timos,” he called.

Aranthur took his helmet off and bowed.

Apparently, on the day of a battle, everyone was friendly. Even Srinan, who was no friend of his.

He walked his horse to the picket in front of the General’s tent. There were a dozen chargers already there. Ariadne was the smallest horse, but, for Aranthur’s money, the handsomest. He gave her a pat and a carefully hoarded turnip and then went to the door of the tent.

One of the guards, an Imperial Axe, nodded.

“She’s with General Roaris,” he said. “I’d wait. If’n I was you.”

The man paused. His fellow Imperial Axe, on the other side of the door, spoke without visibly moving any muscle in his body.

“Which you ain’t,” he said.

“Ain’t?” the first Axe asked.

“You ain’t him.”

“Sod off, Narsar.”

“Bollocks to you, Gart.”

The two blond giants stood as solid as statues of iron.

Aranthur walked back to his horse, fiddled in his saddlebag and found a pipe and some stock. He filled and tamped his pipe, but he didn’t light it. Instead he put it back, carefully; pipeclay broke too easily for rough handling. Instead he took out his kuria crystal, ran a thumb over it, felt its power.

He put the chain over his head, and tucked the crystal into his shirt under his doublet. He took a deep breath, and then another, and used just a touch of the crystal to drop into a light meditation state, from whence he began to review the workings he could effect.

The Secret Walk. The first working he’d ever managed, it could hide him, but not unless certain preconditions were met—darkness, or shadows, or a preoccupied adversary. It was a simple, weak working, and not for battlefields.

The Purifier. A very simple volteia that made water safe to drink. Almost every person in the Empire could cast it.

A complex occulta called the Eye of the Gods. It was actually a cantrip of light with a vast array of modifications that adjusted the very air into a pair of lenses. It was a required element of first-year casting, and people failed out of the Academy because working it was so hard. It was not his best occulta.

The Red Shield, or aspis as the Magi called all the protective occultae. He was merely adequate at casting it, as his brushes with combat had shown. But it cast quickly, and he was learning to trust it. It could be a very powerful protection, but he needed practice…

Leon’s Pieasi, or compulsion. Leon was a long dead Byzas Magos, and his compulsion was both powerful and simple. A first year working. Aranthur had only ever used it on a friendly dog, in class.

The Safian Enhancement. Despite being a much more complex working than any of the others, he was confident that he could cast it in any condition or situation. The experience of writing his will on that particular working while near to death had forever imprinted it on him. It was his in a way that no other spell except the casual spark of fire was his.

A variety of cantrips or volteie that adjusted or made light.

A simple visual enhancement that allowed any caster to “see” sihr and saar, the powers that fuelled occultae. Or rather, the powers that fuelled most of the Academy’s occultae. The Safian spells were all powered by the caster’s own will, a surprisingly different process.

Lately he was working on a Safian Transference. He could cast it, but without sufficient result to justify the expenditure. What ought to be like a puffer shot at close range was more like a breath of foul air. He took it out and played with it in what he imagined as a child’s sandbox, an internal meditational demi-reality that he’d learnt in the first weeks of first year, as if a piece of the Aulos could be sealed off for his own research, which, just possibly, was exactly true. The Master of Arts had told him, repeatedly, that his sandbox would be essential to him later. Only now, on the edge of a battle, did he realise what a useful tool it was.

He held the Safian Transference in his head and rotated it to look at the working. He couldn’t see his flaw. He needed to go back to the grimoire, or perhaps he had the starting conditions in a flawed way…

“Timos,” said a deep voice.

He released the trance.

The Jhugj, Drek Coryn Ringkoat, stood at a safe distance.

Aranthur bowed. “Syr Ringkoat.”

“Syr Timos,” the Jhugj said. “General Jackass has taken his orders and left us. It’s safe to come in. She’s in a mood, but then, so am I. You playing with fire there, Timos?”

Indeed, the grass under his left foot was smouldering.

Aranthur stepped away, and considered. The smoking grass had a pungent, piney smell, not unpleasant. The sole of his left foot was hot.

Something in his transference was draining saar. Into the ground.

Interesting. Distracting.

“Come back to us, little sorcerer.” Ringkoat grinned.

Aranthur shook his head. “I’m with you.”

He followed Ringkoat into the great pavilion. A dozen of the General’s Black Lobsters were in the outer room, most of them fully armoured.

“Syr Timos, ma’am,” the Jhugj called out.

“Timos? Message,” the General snapped.

She was also fully dressed, in a long velvet coat with an incredibly embroidered buff coat over it, lined and slashed in silk, the hide brushed like tan velvet itself and so thick it would turn almost any sword cut. She had a fitted breastplate over the coat and Myr Jeninas, the Buccaleria Primas of the Black Lobsters, was holding her helmet.

“For the Capitan Pasha,” she said. “Go. Compliments. Praise. Do the civil.”

That was all. Aranthur took the scroll tube and mounted as the General’s black unicorn was brought from the horse lines. The animal was so big that it dwarfed the big cavalry horses, and its golden eyes seemed to glow. Aranthur could feel the thing’s occult power.

He edged around it and let Ariadne have her head. In three strides he was galloping up, over the ridge, and down into the chaos and jumble of the Attian camp. Here, too, tens of thousands of men and women were forming—a veritable tide of horseflesh off to the left, and in the centre, six great blocks of the famous Yaniceri. They had standards with black horsetails, and drums of their own, and four sweating slaves carrying bronze cauldrons at the centre of every regiment. Aranthur looked at them with fascination, as they were the traditional enemies of his folk, at least in tales. Up close, they were heavily bearded, and his father or his uncle could have dropped into any of their regiments and vanished; the same height, the same noses, the same look.

He raised a hand in salute, and a Yaniceri officer raised a mace.

He galloped by. There was no need to ask directions; the Capitan Pasha’s pavilion was the largest. It was also bright red, and set in the centre of the apparent chaos of the Attian camp.

Aranthur slowed to a canter, and then reined in, and the Sipahis, the Attian knights, parted for him. The Capitan Pasha wore armour of blued steel and gold over the finest maille Aranthur had ever seen, and under it, a deep, rich purple khaftan of silk that shone through the maille in the rising sun.

“Now let all the gods and goddesses rejoice, and be praised,” the Capitan Pasha said. “A messenger from our dear Myr Tribane.”

He held out a strong white hand on which the fine red hairs stood out.

Aranthur handed him the tube.

The Capitan Pasha cracked the wax and took out a scroll. Inside the scroll were six silver sticks.

“Ah! Wonderful.”

The pasha was speaking in Armean. The Attian court spoke mostly Armean; Attian was for peasants, or so Aranthur had been told at the Academy.

“Any message?”

“No, my lord,” Aranthur said. “Except Myr Tribane’s compliments. She wishes your highness a glorious morning and the day of a hero, with a sunset of felicity.”

“See now! Here is the tongue of a poet in a barbarian!”

The Capitan Pasha slapped his back. The Attian commander was a large man, almost a giant. Up close, he smelled of spikenard and lemon.

Aranthur backed Ariadne a few steps. He was conscious that twenty fine horsemen were watching him.

The pasha shook his head. “Eloquence and diligence deserve a reward.” He reached up, to the saddle of his warhorse, which waited behind him, and took from the saddle a long, gold-mounted puffer. “Here. Kill our enemies with something beautiful.”

Aranthur leant out and took the puffer. Despite its length, it was fine and well-balanced. The butt was shaped like an eagle’s talon holding a ball, which proved to be a detailed globe of the world.

“Highness, I am unworthy,” Aranthur said in his middling Armean. He waited, expecting an answer.

The pasha was reading the scroll. A hand twitched.

“You may retire,” a younger officer said. He said it with a smile. “It’s a battlefield, not a court. And your compliment was well-turned, syr. I am Ulgat Kartal.”

“Aranthur Timos,” he responded. “Arnaut.”

“Hah!” Kartal said. “My hereditary enemy! Many times, we raid your cattle.” He offered his hand.

Aranthur shrugged. “I’m sure we’ve come for yours as well.”

He dropped the magnificent puffer into his empty saddle holster. City militia were expected to provide their own puffers. He’d acquired one in a fight in the City; now he had a second, although it was a hand’s breadth longer and the eagle-claw butt stuck up out of the holster. The rain cover would not go over it.

A problem for another day, Aranthur thought, looking at the brilliant sunrise.

“Of course! Well, today, we are friends. Fight well!”

“And you!” Aranthur paused. “What if he has an answer?”

Kartal waved with the same negligence that Tiy Drako might have.

“The pasha is a great lord, and has his own messengers.”

Aranthur understood. He saluted, and he turned Ariadne and was away. He gave her the signal to gallop, and let her go—a little showy, but there was something about the Attian camp that made him feel that he was on stage.

He reined in at the General’s tent. The sun was fully up; most of the regiments were formed. Across the parade, one of their two regular infantry regiments was filing off from the centre.

Off to the east, the drums rolled, long and low.

“Timos?” the General called. She was standing by her monstrous mount. “Message. Anything from the pasha?”

“No, ma’am,” he said.

“Hmm. Get a fresh horse. Roaris. Fast as you can.”

A liveried Imperial servant gave him a saddled horse and took Ariadne. He sprang into the saddle and took the tube as he passed, flashed a salute and was away, off to the west, where he knew Roaris to be.

He found the Imperial general fifteen minutes later, sitting on his chestnut warhorse at the top of a long hill behind the end of the ridge that held the camp, watching the opposing ridge. He was surrounded by his staff, which was much larger than General Tribane’s.

“Messenger,” someone called.

Aranthur rode up to the general, whom he’d seen twice but to whom he’d never been introduced.

Vanax the Prince Verit Roaris was a very handsome man: almost exactly the same height as Aranthur, strong jawed, with a short beard, a magnificent moustache, and the long nose, brown skin and green eyes of the oldest Byzas families. He rode a fine charger with an elaborate red and gold saddle cloth, and he wore the black and gold colours of his own ancient house, and of the Lions, the party of which he was the acknowledged head, instead of an Imperial uniform. By him was his standard, a golden rose embroidered on a black field, the exact reverse of Tribane’s device.

Prince Verit was pointing at the ridge opposite, speaking to a long-nosed Byzas youth in a magnificent fur-trimmed doublet.

“War is a science, my boy, not some sort of slapdash tomfoolery,” Verit Roaris said. “The slattern has no idea of how war functions, or what it’s all for. I’ll let her wallow in error a little, and then maybe I’ll rescue her from her childish decisions. Or not.”

“But, my lord, we could lose the first line,” the young man insisted.

Aranthur felt he might have seen the young man at Mikal Kallinikos’ home, or perhaps at a fencing salle.

“Shopkeepers and grocers? Always more where they came from, Syr Kanaris,” Roaris said. “Best to thin the herd from time to time, anyway.”

Aranthur cleared his throat.

The aristocrat started, surprised by Aranthur’s quiet approach.

“Who in a thousand iron hells are you, syr?” Roaris spat.

“Timos, syr.”

“One of Tribane’s bed-warmers, eh?”

The general took the scroll tube and opened it. He flicked the scroll open. It too held several silver sticks. He took them and dropped them into a pocket in his buff coat. He smiled slightly, as if he had a private joke, and then nodded.

“Tell her that I understand. She already deigned to inform me of her plans. We are the third line. When the effeminate Attians melt away like butter, we’re to come and save Myr Tribane from her foolishness and her trust of foreigners and her plan to run the world with shopkeepers. Carry on.”

“An Arnaut as a messenger?” laughed one of the staff. “At least you know they can’t read over your shoulder!” he jested.

It was Djinar. Aranthur’s stomach muscles tensed and his horse fidgeted.

Djinar smiled. “Toady. Informer. Liar, cheat,” he said.

Aranthur bowed.

“Aranthur Timos, at your service.”

He smiled easily as he said it, despite his inner turmoil, and he was pleased to see an instant flush of anger on the other man’s face.

Aranthur backed his horse, and Djinar turned away ostentatiously, as if he was beneath the man’s contempt, but Aranthur was trying to imagine…

It was just ten days since he’d seen Djinar on the steps on Rachman’s jewellery shop. With Iralia by his side, and Ansu, they’d faced down the Servant, and captured the poisoned kuria crystals.

He was almost sure that the masked man he’d faced in the shattered doorway of the jeweller’s was Djinar.

And now Djinar was on Roaris’ staff.

Aranthur dashed back to the General’s tent, a distance of almost a mile, trying to imagine how to express his fears. Trying to imagine for himself what it was he feared.

By the time he reined in, most of the infantry was off the parade ground by the officers’ lines. The last of the militia regiments were filing off down the long streets of tents towards the enemy.

The General was gone, as was her bodyguard and her banner. And his precious Ariadne.

Aranthur trotted along the ridge until he could see clearly down into the plain. The black unicorn was easy to spot, and he turned his borrowed mount and galloped down the ridge. On his way down he passed a long line of Attian gonnes, drawn for the most part by bullocks, but just as big and just as magnificent as the Imperial gonnes.

He cantered up, his horse slowing without direction from him. He dismounted by the General. The borrowed horse fidgeted as his weight changed. It flinched away from the General’s unicorn, almost spilling Aranthur in the dust, but he made a dancer’s recovery.

Two grooms took the horse’s bit and pulled it away.

“Timos,” the General said.

Prince Ansu was standing close to her, his reins over his arm. Dahlia was just behind him.

“Ma’am, Vanax Roaris understands he is the third line.” Aranthur couldn’t stop himself from raising an eyebrow to indicate what he thought of General Roaris. “Ma’am, I wish to say—”

“He had better understand,” she said acerbically. “Message. Ansu.”

Prince Ansu stepped forward.

“Vanax Silva,” the General said. “She’s somewhere near the banner of the First in the front line. Ansu, try to find out which of the Attian officers is taking command of their front line.”

“Front line?” Aranthur asked Dahlia.

“We’re fighting in three lines. Big lines.”

“Message. Tarkas. Vanax Kunyard. This message. And then find Centark Equus and tell him to get his arse up here.” The General shrugged. “We don’t have enough cavalry to let some wait around combing their hair.”

She waved Dahlia away and pointed at the next messenger.

“Sasan. Message. Capitan Pasha.”

The Safian stood out in his fine maille and tall helmet. He waved at Aranthur and cantered away.

The line of messengers shuffled forward. Aranthur was now half a dozen from the front: three women and a man he didn’t know, and a man he’d fenced with, who gave him a casual wave. He didn’t have the General’s attention, and as strongly as he desired to share his sudden suspicions, the middle of a battle did not seem the time.

“You knew Kallinikos,” the man said.

“I liked him a great deal,” Aranthur said.

“As did I. I’m Strongarm.”

It was a Northern name—maybe even a Western Isles name—although the man looked perfectly normal, in a dark blue coat with an elaborate black and gold breastplate.

The women and the other man in the messenger queue introduced themselves. The man, as tall as Strongarm, leant forward, as if studying Aranthur carefully.

“By the Lady,” he said. “You’re the lad who saved my bacon in the street, the night of the riot.” He extended a gloved hand, and then stripped the glove with his teeth. “Marcos Klinos, House Klinos. Imperial War Staff.”

Aranthur grinned. They had fought back to back, for no better reason than that they were attacked.

“Syr. I am Aranthur Timos. Pardon my laugh—everyone I’ve ever met seems to be here.”

The man grinned. “At the least, I owe you a cup of wine,” he said, and then his name was called and he rode off.

In front of them, the Yaniceri regiments marched into the front line and deployed. The Attian infantry had the right half of the front line. The two Imperial regular regiments were alternating with the most reliable Imperial militia in the centre. The rest was filled in with squares of City Militia, their pike heads glittering in the strong sunlight. Aranthur had seen at least one regiment of Arnauts, too.

“There we are, then,” Myr Tribane said with satisfaction. “Jennie, we’ve got the front line formed. Go back and tell me how the third line is doing.”

Her Primas saluted and rode away.

The General turned to Aranthur.

“Don’t worry. Your turn is coming. You have a question?”

“Ma’am, when does the battle start?”

“When does any story begin? It started when we decided on this gambit, a year and more ago.” She smiled.

Up close, Aranthur found that her hands were shaking very slightly.

“But today began before dawn, when two thousand Attian irregular cavalry struck their horse lines.” She shrugged. “They weren’t brilliant, but they screwed my opponent’s plans for a rapid approach march, and bought us the time to deploy. Once we’re deployed…”

The drums rolled from the opposing ridge, loud and long. The sound was like the approach of a storm, or the sign of an impending doom.

“Message, Timos,” the General said. “Oral only. Go to the First, and tell the bandmaster, with my compliments, that he may play. We have music, too.”

Aranthur didn’t know whether he should be offended at such an inconsequential errand, but he bowed, and took yet another borrowed horse, and galloped down the ridge. The second line, where the General was standing on a low dimple of a hillock in the centre of the ridge, was almost five hundred paces behind the first line. The first line was a mile and a half wide, and Aranthur’s rapid calculation suggested there were fifteen thousand soldiers in the first line alone.

He knew the flag of the First from drills in the City. He rode up, and saluted the senior centark.

“From the General, for the bandmaster,” he said.

“Be my guest, syr.” The commander was not a nobleman; in fact, from his accent, he was an Arnaut. He pointed to a tall man in an elaborately plumed helmet. “Carry on, brother. You are an Arnaut?”

“Yes, syr.”

The centark smiled. “Go pass your message, lad.”

The officer looked magnificent in a velvet fustanella with a breastplate,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...