- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

SOME SEIZE IT

AND SOME HAVE THE WISDOM NEVER TO WIELD IT

The Red Knight has stood against soldiers, against armies and against the might of an empire without flinching. He's fought on real and on magical battlefields alike, and now he's facing one of the greatest challenges yet.

A tournament.

A joyous spring event, the flower of the nobility will present arms and ride against each other for royal favour and acclaim. It's a political contest - and one which the Red Knight has the skill to win. But the stakes may be higher than he thinks. The court of Alba has been infiltrated by a dangerous faction of warlike knights, led by the greatest knight in the world: Jean de Vrailly - and the prize he's fighting for isn't royal favour, but the throne of Alba itself.

Where there is competition there is opportunity; the question is, will the Red Knight take it? Or will the creatures of the Wild seize their chance instead . . .

"A stirring, gritty and at times quite brutal epic fantasy" Tor.com

"This series promises to be the standout epic fantasy for the ages" Fantasy Book Critic

Read by Neil Dickson

(p) 2015 Hachette Audio

Release date: October 20, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 608

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

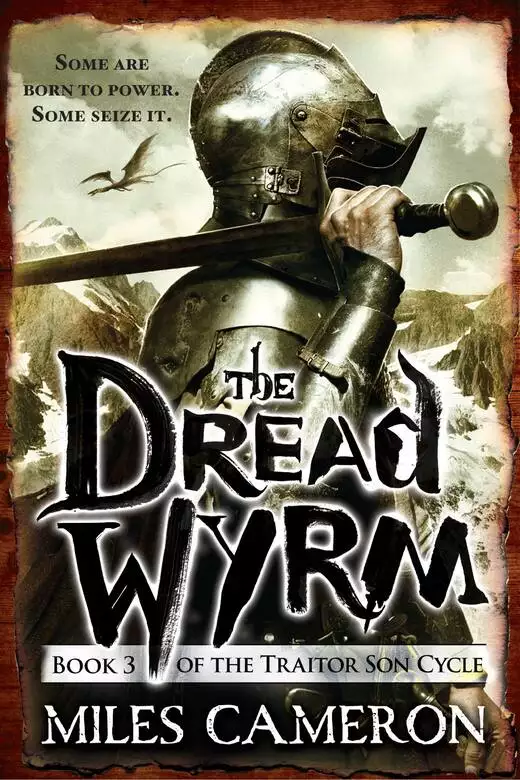

The Dread Wyrm

Miles Cameron

Sauce was standing on a table in a red kirtle that laced up under her left arm—laces that showed she wore no linen under it. She was singing.

There’s a palm bush in the garden where the lads and lassies meet,

For it would not do to do the do they’re doing in the street,

And the very first time he saw it he was very much impressed,

For to have a jolly rattle at my cuckoo’s nest.

Aye the cuckoo, oh the cuckoo, aye the cuckoo’s nest,

Aye the cuckoo, oh the cuckoo, aye the cuckoo’s nest,

I’ll give any man a shilling and a bottle of the best,

If he ruffles up the feathers on my cuckoo’s nest.

Well some likes the lassies that are gay well dressed,

And some likes the lassies that are tight about the waist,

But it’s in between the blankets, that they all likes the best,

For to have a jolly rattle at my cuckoo’s nest.

I met him in the morning and he had me in the night,

I’d never been that way before and wished to do it right,

But he never would have found it, and he never would have guessed,

If I had not shown him where to find the cuckoo’s nest.

I showed him where to find it and I showed him where to go,

In amongst the stickers, where the young cuckoos grow,

And ever since he found it, he will never let me rest,

’Til he ruffles up the feathers on my cuckoo’s nest.

It’s thorny and it’s sprinkled and it’s compassed all around,

It’s tucked into a corner where it isn’t easy found,

I said, “Young man you blunder…” and he said, “It isn’t true!”

And he left me with the makings of a young cuckoo.

Her voice wasn’t beautiful—it had a bit of a squawk to it, more like a parrot than a nightingale, as Wilful Murder said to his cronies. But she was loud, and raucous, and everyone knew the tune and the chorus.

Everyone, in this case, being everyone in the common room of the great stone inn under the Ings of Dorling, widely reputed to be the largest inn on the whole of the world. The common room had arches and bays, like a church, and massive pillars set straight onto stone piers that went down into the cellars below—cellars that were themselves famous. The walls were twice the height of a man, and more, hung with tapestries so old and so caked in old soot and ash and six hundred years of smoke as to be nearly indecipherable, although there appeared to be a great dragon on the longest wall, the back wall, against which ran the Keeper’s long counter where the staff, and a few favoured customers, took refuge from the army of customers out on the floor.

Because on this, the coldest spring night of Martius yet, with snow outside on their tents, the Company of the Red Knight—that is, that part of the company not snug in barracks back in Liviapolis—packed the inn and its barns to the rafters, along with several hundred Moreans, some Hillmen from the drove, and a startling assortment of sell-swords and mercenaries, whores, travelling players, and foolish young men and women in search of what they no doubt hoped would be “adventure,” including twenty hot-headed young Occitan knights, their pet troubadour and their squires, all armed to the teeth and eager to be tested.

The crowd standing packed on the two-inch-thick oak boards of the common room floor was so dense that the smallest and most attractive of the Keeper’s daughters had trouble making her way to the rooms behind the common. Men tried to make way for her, with her wooden tray full of leather jacks, and could not.

The Keeper had four great bonfires roaring in the yard and trestle tables there; he was serving ale in his cavernous stone barn, but everyone wanted to be in the inn itself, and the cold snap that froze the water in the puddles and drove the beasts of the drove to huddle close in the great pens and folds on the Ings above the inn was also forcing the greatest rush of customers he’d ever experienced to pack his common room so tightly that he was afraid men would die or, worse, buy no ale.

The Keeper turned to the young man who stood with him on the staff side of the bar. The young man had dark hair and green eyes and wore red. He was watching the common room with the satisfaction that an angel might show for the good works of the pious.

“Your blighted company and the drove at the same time? Couldn’t you have come a week apart? There won’t be enough forage for you in the hills.” The Keeper sounded shrill, even to his own ears.

Gabriel Muriens, the Red Knight, the Captain, the Megas Dukas, the Duke of Thrake, and possessor of another dozen titles heaped on him by a grateful Emperor, took a long pull from his own jack of black, sweet winter ale and beamed. “We’ll have forage,” he said. “It’s been warmer in the Brogat. It’s spring on the Albin.” He smiled. “And this is only a tithe of my company.” The smile grew warmer as he watched the recruiting table set against the wall. The adventurous young of six counties and three nations were cued up. “But it’s growing,” he added.

Forty of the Keeper’s people, most in his livery and all his kin, stood like soldiers at the long counter and served ale at an astounding rate. Gabriel watched them with the pleasure that a professional receives in watching others practise their craft—he enjoyed the smooth efficiency with which the Keeper’s wife kept her tallies, the speed with which money was collected or tally sticks were notched, and the ready ease with which casks were broached, emptied into pitchers, the said pitchers filled flagons or jacks or battered mugs and cans, all the while the staff moving up to the counter and then back to the broached kegs with the steady regularity of a company of crossbowmen loosing bolts by rotation and volley.

“They all seem to have coin to spend,” the Keeper admitted grudgingly. His elder daughter Sarah—a beautiful girl with red hair, married and widowed and now with a bairn, currently held by a cousin—stood where Sauce had been and sang an old song—a very old song. It had no chorus, and the Hillmen began to make sounds—like a low polyphonic hum—to accompany her singing. When one of the Morean musicians began to pluck the tune on his mandolin, a rough hand closed on his shoulder and he ceased.

The Keeper watched his daughter for long enough that his wife stopped taking money and looked at him. But then he shrugged. “They have money, as I say. You had some adventures out east, I hear?”

The Red Knight settled his shoulder comfortably into the corner between a low shelf and a heavy oak cupboard behind the bar. “We did,” he said.

The Keeper met his eye. “I’ve heard all the news, and none of it makes much sense. Tell it me, if you’d be so kind.”

Gabriel paused to finish his ale and look at the bottom of his silver cup. Then he gave the Keeper a wry smile. “It’s not a brief story,” he said.

The Keeper raised an eyebrow and glanced out at the sea of men. Ser Alcaeus was being called for by the crowd, and his name was chanted. “I couldn’t leave you even if I wanted,” the Keeper said. “They’d lynch me.”

Gabriel shrugged. “So. Where do you want me to begin?”

Sarah, flushed from the effort of singing, came under the bar and took her baby back from her cousin. She grinned at the Red Knight. “You’re going to tell a story?” she said. “Christ on the cross, Da! Everyone will want to hear!”

Gabriel nodded. Ale had magicked its way into his silver cup. The magick had been performed by a muscular young woman with a fine lace cap. She smiled at him.

“It’s not an easy story to start, sweeting.” He returned the serving girl’s smile with genteel interest.

Sarah wasn’t old enough to take much ambiguity. “Start at the beginning!” she said.

Gabriel made an odd motion with his mouth, almost like a rabbit moving its nose. “There is no beginning,” he said. “It just goes on and on into the past—an endless tale of motion and stillness.”

The Keeper rolled his eyes.

Gabriel realized he’d had too much to drink. “Fine. You recall the fight at Lissen Carak.”

Just behind the Red Knight, Tom Lachlan roared his dangerous laugh. Gabriel Muriens snapped his head around, and Lachlan—the Drover, now, almost seven feet of tartan-and grey-clad muscle, with a broad, silver-mounted belt and a sword as long as a shepherd’s crook—flipped the gate back on the bar and stepped through. “Boyo, we all remember the fight at Lissen Carak. That was a fight.”

Gabriel shrugged. “The magister who now styles himself Thorn—” He smiled grimly, paused, and pointed at a glass-shielded candle on the cupboard. A dozen moths of various sizes flitted about it.

Across the press of the crowd, Mag felt the pull of ops. She tensed.

He stood on the bright new mosaic floor of his memory. Prudentia stood once more on her plinth, and her statue was now a warm ivory rather than a cold marble, the features more mobile than they had been in his adolescence and her hair the same grey-black he remembered from his youth.

He knew in his heart that she was now a simulacrum not an embodied spirit, but she was the last gift that Harmodius the magister had left him, and he loved having her back.

“Immolate tinea consecutio aedificium,” he said.

Prudentia frowned. “Isn’t that a bit… dramatic?” she asked.

He shrugged. “I’m renowned for my arrogance and my dramatic flair,” he said. “He’ll be blind and with a little luck, he’ll attribute it to the said arrogance. Consider it a smokescreen for our visitor. If he’s coming.”

She didn’t shrug. But somehow she conveyed a shrug, perhaps a sniff of disapproval, without moving an ivory muscle.

“Katherine! Thales! Iskander!” he said softly, and his memory palace began to spin.

The main room—the casting chamber—of his palace was constructed, or remembered, as a dome held aloft with three separate sets of arches. In among the arches were nooks containing statues of worthies; his last year as a practitioner had clarified and enhanced his skills to add another row.

On the bottom row were the bases of his power—represented by thirteen saints of the church, six men, six women, and an androgynous Saint Michael standing between them. Above the saints stood another tier, this one of the philosophers who had informed his youth—ancients of one sect or another from various of the Archaic eras. But now, above them stood a new tier; twelve worthies of a more modern age; six women and six men and one cloaked figure. Harmodius had installed them, and Gabriel had some reservations about what they might mean—but he knew Saint Aetius, who killed his emperor’s family; he knew King Jean le Preux, who stopped the Irk Conquest of Etrusca after the catastrophic collapse of the Archaic world; he knew Livia the empress and Argentia the great war queen of Iberia.

As he called the names, the statues he indicated moved—indeed, the whole tier on which they stood moved until all three tiers of statues had moved the figures he named to the correct position over the great talismanic symbol that guarded the green door at the end of the chamber. Recently, there had appeared another door, exactly opposite the green door—a small red door with a grille. He knew what lay there, but he went out of his way not to go too close to it. And set in the floor by Prudentia’s plinth was a bronze disc with silver letters and a small lever. Gabriel had designed it himself. He hoped never to use it.

“Pisces,” he said.

Immediately under the lowest tier of statues there was a band. The band looked like bronze, and on it were repoussed—apparently—and engraved and decorated in gold and silver and enamel a set of thirteen zodiacal symbols. This band also rotated, although it did so in the opposite direction to the statues.

Clear golden sunlight fell through the great carved crystal that was the dome above them, and it struck the fish of pisces and coalesced into a golden beam.

The great green door opened. Beyond it was a sparkling grate, as if someone had built a portcullis of white-hot iron. Through its grid came a green radiance that suffused the casting chamber and yet was somehow defined by the golden light of the dome.

He grinned in satisfaction and snapped his fingers. Every moth in the great inn fell to the floor, dead.

Sarah laughed. “Now that’s a trick,” she said. “How about mice?”

Her son, just four months old, looked at her with goobering love and tried to find her nipple with his mouth.

Gabriel laughed. “As I was saying, the magister who now styles himself Thorn, once known as Richard Plangere, led an army of the Wild against Lissen Carak. He enlisted all the usual allies: Western boglins, stone trolls, some Golden Bears of the mountain tribes and some disaffected irks from the Lakes; wyverns and wardens. All of the Wild that’s easy to seduce, he took for his own. He also managed to sway the Sossag of the Great House, those who live in the Squash Country north of the inland sea.”

“And they killed Hector! God’s curse on them.” Sarah’s hate for Hector’s killer was as bright as her hair.

The Red Knight looked at the young woman and shook his head. “I can’t join you in the curse, sweeting. They have Thorn as a houseguest, now. They left him, you know. And—” He looked at the Drover. “The Sossag and the Huran would see us as the murdering savages who stole their land.”

“A thousand years ago!” Bad Tom spat.

Gabriel shrugged. At his back, Ser Alcaeus was playing a kithara from the ancient world and singing an ancient song in a strange, eerie voice. Because every word he sang was in the true Archaic, the air shimmered with ops and potentia.

Ser Michael slipped under the gate of the bar and found space to lean. Kaitlin, his wife, now so heavily pregnant that she waddled instead of walking, was already snug in one of the inn’s better beds. Behind him, Sauce—Ser Alison—glared at a Hillman until he pushed more strongly against his mates and made room for her slight form to ease by him.

He made a natural, but ill-judged, decision to run his hand over her body as she passed, and found himself wheezing on the hard oak boards. Her paramour, Count Zac, stepped on the fallen Hillman and vaulted over the bar.

The Hillman rose, his face a study in rage, to find Bad Tom’s snout within a hand’s breadth of his own. He flinched.

Tom handed the man—one of his own—a full flagon of ale. “Go drink it off,” he said.

The Keeper glared at the incursion of Albans now encroaching on the smooth delivery of ale. “Didn’t I rent you a private room?” he asked the captain.

“Do you want to hear this tale, or not?” the captain said.

The Keeper grunted.

“So Thorn—” Every man and woman in earshot was aware that the captain or the duke—or whatever tomfool title he went by these days—had just said Thorn’s name three times.

Three hundred Albin leagues north and west, Thorn stood in a late-winter snow shower. He stood on the easternmost point of the island he had made his own, his place of power, and great breakers of the salt-less inner sea slammed against the rock of the island’s coast and rose ten times the height of a man into the air, driven by the strong east wind.

Out in the bay, the ice was breaking.

Thorn had come to this exposed place to prepare a working—a set of workings, a nest of workings—against his target: Ghause, wife of the Earl of Westwall. He felt his name—like the whisper of a moth’s wings in the air close to a man’s face on a hot summer night. But many said his name aloud, in whispers, often enough that he didn’t always pay heed. But in this case, the naming was accompanied by a burst of power that even across the circle of the world made itself felt in the aethereal.

The second calling was softer. But such things run in threes, and no user of the art could ever be so ignorant as to attract his attention and leave the third naming incomplete.

The third use was casual—contemptuous. Thorn’s sticklike, bony hands flinched.

But the Dark Sun was no casual enemy, and he stood in a place of power surrounded by friends. And he had made Thorn blind, as he did on a regular basis. Carefully, with the forced calm that, in a mere man, would have involved the gritting of teeth, Thorn mended the small gap in the aether made by the calling of his name, and went back to crafting his working.

But his patience had been interrupted and his rage—Thorn thought dimly around the black hole in his memory that once he had been against rage—flowed out. Some of the rage he funnelled into his working against Ghause—what better revenge? But still he felt that the Dark Sun made him small, and he hated.

And so, without further thought, he acted. A raid was redirected. A sentry was killed. A warden—a daemon lord, as men would call him—was suborned, his sense of reality undermined and conquered.

Try that, mortal man, Thorn thought, and went back to his casting.

In doing so, like a bird disturbed in making a spring nest, he dropped a twig. But consumed by rage and hate, he didn’t notice.

“Attacked Lissen Carak, and we beat him. He made a dozen mistakes to every one we made—eh, Tom?” Gabriel smiled.

The giant Hillman shrugged. “Never heard you admit we made any mistakes at all.”

Ser Gavin chose to lean against the bar on the other side. “Imagine how Jehan would tell this tale if he was here,” he said.

“Then it would be nothing but my mistakes,” Gabriel said, but with every other man and woman in red, he raised his cup and drank.

“Any road, we beat him,” Tom said. “But it wasn’t no Chaluns, was it? Nor a Battle of Chevin.” Both battles—a thousand years and more apart—had been glorious and costly victories of the forces of men over the Wild.

Gabriel shrugged. “No—it was more like a skirmish. We won a fight in the woods, and then another around the fortress. But we didn’t kill enough boglins to change anything.” He shrugged. “We didn’t kill Plangere or change his mind.” He looked around. “Still—we’re not dead. Round one to us. Eh?”

Bad Tom raised his mug and drank.

“In summer we rode east to the Empire. To Morea.”

“That’s more like it,” said the Keeper.

“It’s a tangled thread. The Emperor wanted to hire us, but we never knew what for, because by the time we heard, he’d been taken captive and his daughter Irene was on the throne. And Duke Andronicus was trying to take the city.”

“By which our duke means Liviapolis,” Wilful Murder said to his awestruck new apprentice archer, Diccon, a boy so thin and yet so muscular that most of the women in the common room had noticed him. “Biggest fewkin’ city in the world.” Wilful knew what it meant when all the officers gathered, and he’d wormed his way patiently into the story circle.

The Keeper raised an eyebrow. His daughter laughed. “Way I hear it, she had ’im taken so she could have the power.”

“Nah, that’s just rumour,” her father said.

The Red Knight’s companions didn’t say a thing. They didn’t even exchange looks.

“We arrived,” the captain said with relish, “in the very nick of time. We routed the usurper—”

Tom snorted. Michael looked away, and Sauce made a rude gesture. “We almost got our arses handed to us,” she said.

The captain raised an eyebrow. “And after a brief winter campaign—”

“Jesu!” spat Sauce. “You’re leaving out the whole story!”

“By Tar’s tits!” Bad Tom said.

Just for a moment, at his oath, a tiny flawed silence fell so that his words seemed to carry.

“What did you just say?” Gabriel asked, and his brother Gavin looked as if one of Tom’s big fists had struck him.

Bad Tom frowned. “It’s a Hillman’s oath,” he said.

Gabriel was staring at him. “Really?” he asked. He sighed. “At any rate, after a brief but very successful winter campaign, we destroyed the duke’s baggage and left his army helpless in the snow and then made forced marches—”

“In fewkin’ winter!” Bad Tom interjected.

“Across the Green Hills to Osawa to retrieve the Emperor’s share of the fur trade.” The captain smiled. “Which paid off our bets, so to speak.”

“You ain’t telling any part of this right,” Sauce said.

Gabriel glared at her—she couldn’t tell, despite knowing him many years, whether this was his instant anger or a mock-glare. “Why don’t you tell it, then,” he said.

She raised and lowered her eyebrows very rapidly. “All right then.” She looked to the Keeper. “So we—” She paused. “Got very lucky and—” She thought of the security ramifications and realized she couldn’t actually name Kronmir, the spy, who had left the enemy and joined them and even now was making his way to Harndon with Gelfred and the green banda. “And… we… er…”

Gabriel met her eye and they both laughed.

“As I was saying,” he went on. “A month ago and more, we found through treason in the former duke’s court in Lonika the location of the Emperor, and we staged a daring rescue, met his army in the field and beat it, and killed his son Demetrius.”

“Who had already murdered his father,” Ser Alcaeus muttered, joining the circle.

“So we returned the Emperor to his loving daughter and grateful city, took our rewards, and came straight here to spend them,” the Red Knight said. “Leaving, as you don’t seem to notice, more than half our company to guard the Emperor.”

“His mouth is moving and I can’t understand a word he says.” Bad Tom laughed. “Except that we’re all still being paid.”

Ser Michael joined the giant. “You told what happened without any part of the story,” he said.

“That’s generally what happens,” Gabriel agreed. “We call the process ‘History.’ Anyway, we’ve been busy, we have silver, and we’re all on our way south. We’ll help Tom get his beeves to market and then most of us will go to the king’s tournament at Harndon at Pentecost.”

“With a stop in Albinkirk,” Ser Michael said.

Gabriel glared at his protégé, who was unbowed.

“To see a nun,” Michael added, greatly daring.

But the captain’s temper was well in check. He merely shrugged. “To negotiate a council of the north country,” Gabriel corrected him. “Ser John Crayford has invited a good many of the powers. It’ll run alongside the market at Lissen Carak.”

The Keeper nodded. “Aye—I’ve had my herald. I’ll be sending one o’ my brats wi’ Bad Tom. It’s a poor time to go, for mysel.” He wrinkled his nose. “And ye—pardon me. But you may be the king o’ sell-swords, but what ha’ ye to do wi’ the north country?”

Gabriel Muriens smiled. For a moment, he looked rather more like his mother than he would have liked. “I’m the Duke of Thrake,” he said. “My writ runs from the Great Sea to the shores at Ticondaga.”

“Sweet Christ and all the saints,” the Keeper said. “So the Muriens now hold the whole of the wall.”

Gabriel nodded. “The Abbess has some of it, out west. But yes, Keeper.”

The Keeper shook his head. “The Emperor gave you the wall?”

Sauce had a look on her face as if she’d never considered the implications of her captain being the Lord of the Wall. Bad Tom looked as if an axe had hit him between the eyes. Gavin was looking at his brother with something like suspicion.

Only Ser Michael looked unfazed. “The Emperor,” he said lightly, “is very unworldly.” He scratched his beard. “Unlike our esteemed lord and master.”

Whatever reaction this comment might have received was lost when a slim man with jet-black hair emerged from the dumbwaiter that brought kegs from the deep cellars. The Keeper’s folk rode the man-powered elevator from time to time, usually for a prank or when ale was needed very quickly; but most of the folk standing on the staff side of the bar had never seen the black-haired man before. He wore a well cut, very short black doublet and matching hose and had pale, almost translucent skin, like depictions of particularly ascetic saints.

“Master Smythe,” Gabriel said, with a bow.

The Keeper puffed his cheeks. “Could we,” he said carefully, “move this to another room?”

One by one they passed under the bar into the outer common room and then forced their way to the end of the great hall and out into a private solar under the eaves. It was chilly, and the young woman who had so carefully given the captain the eye knelt gracefully and began to make up a fire. She lit it with a taper and then curtsied—but this time her bright eyes were for Master Smythe.

Master Smythe surprised them all by watching her as she left for wine and ale, and a tiny wisp of smoke came from one nostril. “Ah, the children of men,” he said. He raised an eyebrow at Gabriel. “What curious animals you are. You don’t want her, but you resent her wanting me.”

Gabriel’s head snapped back as if he’d been struck and, behind him, Father Arnaud choked on his ale and hid his face.

“Must you always say what other people are thinking?” asked the Red Knight. “It would be a bad enough habit with your own thoughts. Please don’t do it with mine.”

Master Smythe smiled politely. “But why resent me?”

Gabriel exhaled for so long that it wasn’t a sigh. It was like a physical release of tension. His eyes moved—

He shrugged. “I miss the company of women in my bed,” he said with flat honesty. “And I like to be desired.”

Master Smythe nodded. “As do I. Do you perceive me as a rival?”

Sauce stepped in. “Given that you’re some sort of god and we’re not, I’m sure he does.” She smiled at the black-haired man. “But he’ll get over it.”

“I can fight my own fights,” the Red Knight said, putting a hand on Sauce’s shoulder. He nodded graciously to Master Smythe. “We are allies. Allies are—often—potential rivals. But I think you put too much on my surface thoughts and my animal reactions. I like a wench, and sometimes,” he smiled, “I do things from habit.”

Master Smythe nodded. “For my part, I am a surly companion, my allies. Do you know that before this little matter of the sorcerer in the north, I was quite happy to lie on my mountain and think? I retreated from this world for reasons. And as I play this game, the reasons seem to me ever more valid.” He looked around. “I am not filled with a sense of ambition or challenge, but just a vague fatigue. Facing our shared foe—” He paused. “I’d really rather that he just went off to another plot, another world.”

The serving girl returned. She had broad shoulders—extraordinarily broad. She had a peculiar grace, as if life in a big body had forced her to some extraordinary exercises.

The Red Knight leaned over. “You’re a dancer!” he said, delighted.

She bobbed her head. “Yes, m’lord,” she said.

“A Hillman!” Gabriel said.

Master Smythe laughed. “Surely—surely we call her a Hillwoman.”

She blushed and looked at the ground and then raised her eyes—to Master Smythe.

Gabriel took a sip of ale. “I think I’ve lost this round,” he said. Sauce rolled her eyes and leaned against the table.

The fire roared to life, the kindling bursting into an almost hermetical fire so that the small room was instantly warmer.

Father Arnaud whispered something as Bad Tom pushed in, and Sauce roared. “It’s like watching two lions with a bunny,” she said.

Father Arnaud was less than amused.

Master Smythe took his ale and sat in the chair at the end of the table, and the rest of them made do with two benches and a collection of stools brought by a trio of boys. There wasn’t really room for everyone—Ser Michael was filling out rapidly and bid fair to reach Bad Tom’s size; Bad Tom folded himself into a nook by the chimney, as if storing heat for his future of sleeping out on the moors with his flocks. Sauce hooked a stool across from the captain. Mag came in and settled on the bench next to the captain, and Gavin took the other side. The Keeper took a stool at the far end of the table from Master Smythe. Ser Alcaeus stood behind the captain, leaning with his shoulders wedged into the oak panels. Wilful Murder stood in the doorway for as long as a nun might say a prayer, and the captain made a sign with his hand and the old archer slipped away.

“Where is the remarkable young man?” Master Smythe asked.

“We have a whole company of remarkable young men.” Gabriel nodded. “You mean Ser Morgon?”

Master Smythe nodded and blinked. “Ah—I expected him here. He is in Morea.”

“Where he belongs, at school.” Ser Gabriel leaned forward.

“You have left half your company in Morea?” Master Smythe asked.

“Ser Milus deserved an independent command. Now he has it. He has almost all the archers and—” The Red Knight paused.

Ser Michael laughed. “And all the knights we trust.”

Master Smythe nodded. “Hence your escort of Thrakian… gentlemen.”

Ser Gabriel nodded. “I don’t think any of them plan to put a knife in my ribs, but I think it’s better for everyone that they aren’t in Thrake for a year or two.”

Count Zac came in and, at a sign from Sauce, closed the door with his hip. He had a tray full of bread and olive oil. He went and balanced with Sauce on a small stool.

“And we have Count Zacuijah to keep the rest of us in line,” Ser Gabriel said.

“And the magister you carried in your head?” asked Master Smythe.

There were some blank looks and, again, Sauce made a face that

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...