- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

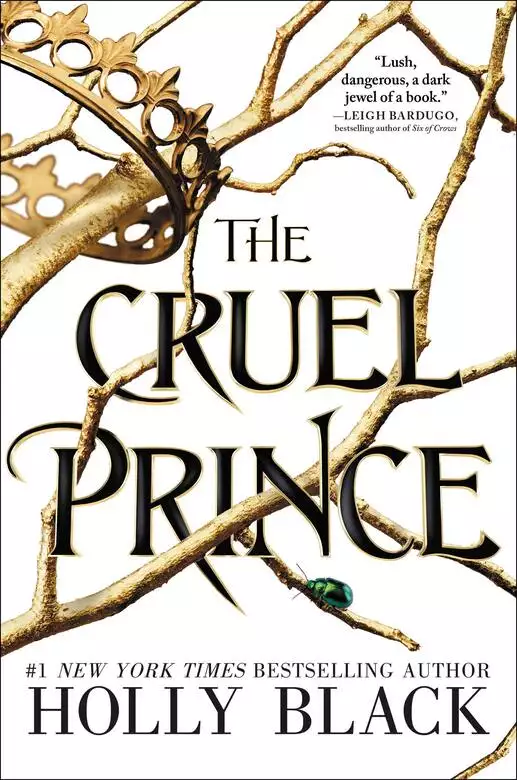

Synopsis

Of course I want to be like them. They're beautiful as blades forged in some divine fire. They will live forever. And Cardan is even more beautiful than the rest. I hate him more than all the others. I hate him so much that sometimes when I look at him, I can hardly breathe. One terrible morning, Jude and her sisters see their parents murdered in front of them. The terrifying assassin abducts all three girls to the world of Faerie, where Jude is installed in the royal court but mocked and tormented by the Faerie royalty for being mortal. As Jude grows older, she realises that she will need to take part in the dangerous deceptions of the fey to ever truly belong. But the stairway to power is fraught with shadows and betrayal. And looming over all is the infuriating, arrogant and charismatic Prince Cardan ... Dramatic and thrilling fantasy blends seamlessly with enthralling storytelling to create a fully realised and seductive world, brimful of magic and romance.

Release date: December 4, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Cruel Prince

Holly Black

The man walked to the door and lifted his fist to knock.

Inside the house, Jude sat on the living room rug and ate fish sticks, soggy from the microwave and dragged through a sludge of ketchup. Her twin sister, Taryn, napped on the couch, curled around a blanket, thumb in her fruit-punch-stained mouth. And on the other end of the sofa, their older sister, Vivienne, stared at the television screen, her eerie, split-pupiled gaze fixed on the cartoon mouse as it ran from the cartoon cat. She laughed when it seemed as if the mouse was about to get eaten.

Vivi was different from other big sisters, but since seven-year-old Jude and Taryn were identical, with the same shaggy brown hair and heart-shaped faces, they were different, too. Vivi’s eyes and the lightly furred points of her ears were, to Jude, not so much more strange than being the mirror version of another person.

And if sometimes she noticed the way the neighborhood kids avoided Vivi or the way their parents talked about her in low, worried voices, Jude didn’t think it was anything important. Grown-ups were always worried, always whispering.

Taryn yawned and stretched, pressing her cheek against Vivi’s knee.

Outside, the sun was shining, scorching the asphalt of driveways. Lawn mower engines whirred, and children splashed in backyard pools. Dad was in the outbuilding, where he had a forge. Mom was in the kitchen cooking hamburgers. Everything was boring. Everything was fine.

When the knock came, Jude hopped up to answer it. She hoped it might be one of the girls from across the street, wanting to play video games or inviting her for an after-dinner swim.

The tall man stood on their mat, glaring down at her. He wore a brown leather duster despite the heat. His shoes were shod with silver, and they rang hollowly as he stepped over the threshold. Jude looked up into his shadowed face and shivered.

“Mom,” she yelled. “Mooooooooom. Someone’s here.”

Her mother came from the kitchen, wiping wet hands on her jeans. When she saw the man, she went pale. “Go to your room,” she told Jude in a scary voice. “Now!”

“Whose child is that?” the man asked, pointing at her. His voice was oddly accented. “Yours? His?”

“No one’s.” Mom didn’t even look in Jude’s direction. “She’s no one’s child.”

That wasn’t right. Jude and Taryn looked just like their dad. Everyone said so. She took a few steps toward the stairs but didn’t want to be alone in her room. Vivi, Jude thought. Vivi will know who the tall man is. Vivi will know what to do.

But Jude couldn’t seem to make herself move any farther.

“I’ve seen many impossible things,” the man said. “I have seen the acorn before the oak. I have seen the spark before the flame. But never have I seen such as this: A dead woman living. A child born from nothing.”

Mom seemed at a loss for words. Her body was vibrating with tension. Jude wanted to take her hand and squeeze it, but she didn’t dare.

“I doubted Balekin when he told me I’d find you here,” said the man, his voice softening. “The bones of an earthly woman and her unborn child in the burned remains of my estate were convincing. Do you know what it is to return from battle to find your wife dead, your only heir with her? To find your life reduced to ash?”

Mom shook her head, not as if she was answering him, but as though she was trying to shake off the words.

He took a step toward her, and she took a step back. There was something wrong with the tall man’s leg. He moved stiffly, as though it hurt him. The light was different in the entry hall, and Jude could see the odd green tint of his skin and the way his lower teeth seemed too large for his mouth.

She was able to see that his eyes were like Vivi’s.

“I was never going to be happy with you,” Mom told him. “Your world isn’t for people like me.”

The tall man regarded her for a long moment. “You made vows,” he said finally.

She lifted her chin. “And then I renounced them.”

His gaze went to Jude, and his expression hardened. “What is a promise from a mortal wife worth? I suppose I have my answer.”

Mom turned. At her mother’s look, Jude dashed into the living room.

Taryn was still sleeping. The television was still on. Vivienne looked up with half-lidded cat eyes. “Who’s at the door?” she asked. “I heard arguing.”

“A scary man,” Jude told her, out of breath even though she’d barely run at all. Her heart was pounding. “We’re supposed to go upstairs.”

She didn’t care that Mom had told only her to go upstairs. She wasn’t going by herself. With a sigh, Vivi unfolded from the couch and shook Taryn awake. Drowsily, Jude’s twin followed them into the hallway.

As they started toward the carpet-covered steps, Jude saw her father come in from the back garden. He held an axe in his hand—forged to be a near replica of one he’d studied in a museum in Iceland. It wasn’t weird to see Dad with an axe. He and his friends were into old weapons and would spend lots of time talking about “material culture” and sketching ideas for fantastical blades. What was odd was the way he held the weapon, as if he was going to—

Her father swung the axe toward the tall man.

He had never raised a hand to discipline Jude or her sisters, even when they got into big trouble. He wouldn’t hurt anyone. He just wouldn’t.

And yet. And yet.

The axe went past the tall man, biting into the wood trim of the door.

Taryn made an odd, high keening noise and slapped her palms over her mouth.

The tall man drew a curved blade from beneath his leather coat. A sword, like from a storybook. Dad was trying to pull the axe free from the doorframe when the man plunged the sword into Dad’s stomach, pushing it upward. There was a sound, like sticks snapping, and an animal cry. Dad fell to the vestibule carpet, the one Mom always yelled about when they tracked mud on it.

The rug that was turning red.

Mom screamed. Jude screamed. Taryn and Vivi screamed. Everyone seemed to be screaming, except the tall man.

“Come here,” he said, looking directly at Vivi.

“Y-you monster,” their mother shouted, moving toward the kitchen. “He’s dead!”

“Do not run from me,” the man told her. “Not after what you’ve done. If you run again, I swear I—”

But she did run. She was almost around the corner when his blade struck her in the back. She crumpled to the linoleum, falling arms knocking magnets off the fridge.

The smell of fresh blood was heavy in the air, like wet, hot metal. Like those scrubbing pads Mom used to clean the frying pan when stuff was really stuck on.

Jude ran at the man, slamming her fists against his chest, kicking at his legs. She wasn’t even scared. She wasn’t sure she felt anything at all.

The man paid Jude no mind. For a long moment, he just stood there, as though he couldn’t quite believe what he’d done. As though he wished he could take back the last five minutes. Then he sank to one knee and caught hold of Jude’s shoulders. He pinned her arms to her sides so she couldn’t hit him anymore, but he wasn’t even looking at her.

His gaze was on Vivienne.

“You were stolen from me,” he told her. “I have come to take you to your true home, in Elfhame beneath the hill. There, you will be rich beyond measure. There, you will be with your own kind.”

“No,” Vivi told him in her somber little voice. “I’m never going anywhere with you.”

“I’m your father,” he told her, his voice harsh, rising like the crack of a lash. “You are my heir and my blood, and you will obey me in this as in all things.”

She didn’t move, but her jaw set.

“You’re not her father,” Jude shouted at the man. Even though he and Vivi had the same eyes, she wouldn’t let herself believe it.

His grip tightened on her shoulders, and she made a little squeezed, squeaking sound, but she stared up defiantly. She’d won plenty of staring contests.

He looked away first, turning to watch Taryn, on her knees, shaking Mom while she sobbed, as though she was trying to wake her up. Mom didn’t move. Mom and Dad were dead. They were never going to move again.

“I hate you,” Vivi proclaimed to the tall man with a viciousness that Jude was glad of. “I will always hate you. I vow it.”

The man’s stony expression didn’t change. “Nonetheless, you will come with me. Ready these little humans. Pack light. We ride before dark.”

Vivienne’s chin came up. “Leave them alone. If you have to, take me, but not them.”

He stared at Vivi, and then he snorted. “You’d protect your sisters from me, would you? Tell me, then, where would you have them go?”

Vivi didn’t answer. They had no grandparents, no living family at all. At least, none they knew.

He looked at Jude again, released her shoulders, and rose to his feet. “They are the progeny of my wife and, thus, my responsibility. I may be cruel, a monster, and a murderer, but I do not shirk my responsibilities. Nor should you shirk yours as the eldest.”

Years later, when Jude told herself the story of what happened, she couldn’t recall the part where they packed. Shock seemed to have erased that hour entirely. Somehow Vivi must have found bags, must have put in their favorite picture books and their most beloved toys, along with photographs and pajamas and coats and shirts.

Or maybe Jude had packed for herself. She was never sure.

She couldn’t imagine how they’d done it, with their parents’ bodies cooling downstairs. She couldn’t imagine how it had felt, and as the years went by, she couldn’t make herself feel it again. The horror of the murders dulled with time. Her memories of the day blurred.

A black horse was nibbling the grass of the lawn when they went outside. Its eyes were big and soft. Jude wanted to throw her arms around its neck and press her wet face into its silky mane. Before she could, the tall man swung her and then Taryn across the saddle, handling them like baggage rather than children. He put Vivi up behind him.

“Hold on,” he said.

Jude and her sisters wept the whole way to Faerieland.

I sit on a cushion as an imp braids my hair back from my face. The imp’s fingers are long, her nails sharp. I wince. Her black eyes meet mine in the claw-footed mirror on my dressing table.

“The tournament is still four nights away,” the creature says. Her name is Tatterfell, and she’s a servant in Madoc’s household, stuck here until she works off her debt to him. She’s cared for me since I was a child. It was Tatterfell who smeared stinging faerie ointment over my eyes to give me True Sight so that I could see through most glamours, who brushed the mud from my boots, and who strung dried rowan berries for me to wear around my neck so I might resist enchantments. She wiped my wet nose and reminded me to wear my stockings inside out, so I’d never be led astray in the forest. “And no matter how eager you are for it, you cannot make the moon set nor rise any faster. Try to bring glory to the general’s household tonight by appearing as comely as we can make you.”

I sigh.

She’s never had much patience with my peevishness. “It’s an honor to dance with the High King’s Court under the hill.”

The servants are overfond of telling me how fortunate I am, a bastard daughter of a faithless wife, a human without a drop of faerie blood, to be treated like a trueborn child of Faerie. They tell Taryn much the same thing.

I know it’s an honor to be raised alongside the Gentry’s own children. A terrifying honor, of which I will never be worthy.

It would be hard to forget it, with all the reminders I am given.

“Yes,” I say instead, because she is trying to be kind. “It’s great.”

Faeries can’t lie, so they tend to concentrate on words and ignore tone, especially if they haven’t lived among humans. Tatterfell gives me an approving nod, her eyes like two wet beads of jet, neither pupil nor iris visible. “Perhaps someone will ask for your hand and you’ll be made a permanent member of the High Court.”

“I want to win my place,” I tell her.

The imp pauses, hairpin between her fingers, probably considering pricking me with it. “Don’t be foolish.”

There’s no point in arguing, no point to reminding her of my mother’s disastrous marriage. There are two ways for mortals to become permanent subjects of the Court: marrying into it or honing some great skill—in metallurgy or lute playing or whatever. Not interested in the first, I have to hope I can be talented enough for the second.

She finishes braiding my hair into an elaborate style that makes me look as though I have horns. She dresses me in sapphire velvet. None of it disguises what I am: human.

“I put in three knots for luck,” the little faerie says, not unkindly.

I sigh as she scuttles toward the door, getting up from my dressing table to sprawl facedown on my tapestry-covered bed. I am used to having servants attend to me. Imps and hobs, goblins and grigs. Gossamer wings and green nails, horns and fangs. I have been in Faerie for ten years. None of it seems all that strange anymore. Here, I am the strange one, with my blunt fingers, round ears, and mayfly life.

Ten years is a long time for a human.

After Madoc stole us from the human world, he brought us to his estates on Insmire, the Isle of Might, where the High King of Elfhame keeps his stronghold. There, Madoc raised us—me and Vivienne and Taryn—out of an obligation of honor. Even though Taryn and I are the evidence of Mom’s betrayal, by the customs of Faerie, we’re his wife’s kids, so we’re his problem.

As the High King’s general, Madoc was away often, fighting for the crown. We were well cared for nonetheless. We slept on mattresses stuffed with the soft seed-heads of dandelions. Madoc personally instructed us in the art of fighting with the cutlass and dagger, the falchion and our fists. He played Nine Men’s Morris, Fidchell, and Fox and Geese with us before a fire. He let us sit on his knee and eat off his plate.

Many nights I drifted off to sleep to his rumbling voice reading from a book of battle strategy. And despite myself, despite what he’d done and what he was, I came to love him. I do love him.

It’s just not a comfortable kind of love.

“Nice braids,” Taryn says, rushing into my room. She’s dressed in crimson velvet. Her hair is loose—long chestnut curls that fly behind her like a capelet, a few strands braided with gleaming silver thread. She hops onto the bed beside me, disarranging my small pile of threadbare stuffed animals—a koala, a snake, a black cat—all beloved of my seven-year-old self. I cannot bear to throw out any of my relics.

I sit up to take a self-conscious look in the mirror. “I like them.”

“I’m having a premonition,” Taryn says, surprising me. “We’re going to have fun tonight.”

“Fun?” I’d been imagining myself frowning at the crowd from our usual bolt-hole and worrying over whether I’d do well enough in the tournament to impress one of the royal family into granting me knighthood. Just thinking about it makes me fidgety, yet I think about it constantly. My thumb brushes over the missing tip of my ring finger, my nervous tic.

“Yes,” she says, poking me in the side.

“Hey! Ow!” I scoot out of range. “What exactly does this plan entail?” Mostly, when we go to Court, we hide ourselves away. We’ve watched some very interesting things, but from a distance.

She throws up her hands. “What do you mean, what does fun entail? It’s fun!”

I laugh a little nervously. “You have no idea, either, do you? Fine. Let’s go see if you have a gift for prophecy.”

We are getting older and things are changing. We are changing. And as eager as I am for it, I am also afraid.

Taryn pushes herself off my bed and holds out her arm, as though she’s my escort for a dance. I allow myself to be guided from the room, my hand going automatically to assure myself that my knife is still strapped to my hip.

The interior of Madoc’s house is whitewashed plaster and massive, rough-cut wooden beams. The glass panes in the windows are stained gray as trapped smoke, making the light strange. As Taryn and I go down the spiral stairs, I spot Vivi hiding in a little balcony, frowning over a comics zine stolen from the human world.

Vivi grins at me. She’s in jeans and a billowy shirt—obviously not intending to go to the revel. Being Madoc’s legitimate daughter, she feels no pressure to please him. She does what she likes. Including reading magazines that might have iron staples rather than glue binding their pages, not caring if her fingers get singed.

“Heading somewhere?” she asks softly from the shadows, startling Taryn.

Vivi knows perfectly well where we’re heading.

When we first came here, Taryn and Vivi and I would huddle in Vivi’s big bed and talk about what we remembered from home. We’d talk about the meals Mom burned and the popcorn Dad made. Our next-door neighbors’ names, the way the house smelled, what school was like, the holidays, the taste of icing on birthday cakes. We’d talk about the shows we’d watched, rehashing the plots, recalling the dialogue until all our memories were polished smooth and false.

There’s no more huddling in bed now, rehashing anything. All our new memories are of here, and Vivi has only a passing interest in those.

She’d vowed to hate Madoc, and she stuck to her vow. When Vivi wasn’t reminiscing about home, she was a terror. She broke things. She screamed and raged and pinched us when we were content. Eventually, she stopped all of it, but I believe there is a part of her that hates us for adapting. For making the best of things. For making this our home.

“You should come,” I tell her. “Taryn’s in a weird mood.”

Vivi gives her a speculative look and then shakes her head. “I’ve got other plans.” Which might mean she’s going to sneak over to the mortal world for the evening or it might mean she’s going to spend it on the balcony, reading.

Either way, if it annoys Madoc, it pleases Vivi.

He’s waiting for us in the hall with his second wife, Oriana. Her skin is the bluish color of skim milk, and her hair is as white as fresh-fallen snow. She is beautiful but unnerving to look at, like a ghost. Tonight she is wearing green and gold, a mossy dress with an elaborate shining collar that makes the pink of her mouth, her ears, and her eyes stand out. Madoc is dressed in green, too, the color of deep forests. The sword at his hip is no ornament.

Outside, past the open double doors, a hob waits, holding the silver bridles of five dappled faerie steeds, their manes braided in complicated and probably magical knots. I think of the knots in my hair and wonder how similar they are.

“You both look well,” Madoc says to Taryn and me, the warmth in his tone making the words a rare compliment. His gaze goes to the stairs. “Is your sister on her way?”

“I don’t know where Vivi is,” I lie. Lying is so easy here. I can do it all day long and never be caught. “She must have forgotten.”

Disappointment passes over Madoc’s face, but not surprise. He heads outside to say something to the hob holding the reins. Nearby, I see one of his spies, a wrinkled creature with a nose like a parsnip and a back hunched higher than her head. She slips a note into his hand and darts off with surprising nimbleness.

Oriana looks us over carefully, as though she expects to find something amiss.

“Be careful tonight,” Oriana says. “Promise me you will neither eat nor drink nor dance.”

“We’ve been to Court before,” I remind her, a Faerie nonanswer if ever there was one.

“You may think salt is sufficient protection, but you children are forgetful. Better to go without. As for dancing, once begun, you mortals will dance yourselves to death if we don’t prevent it.”

I look at my feet and say nothing.

We children are not forgetful.

Madoc married her seven years ago, and shortly after, she gave him a child, a sickly boy named Oak, with tiny, adorable horns on his head. It has always been clear that Oriana puts up with me and Taryn only for Madoc’s sake. She seems to think of us as her husband’s favored hounds: poorly trained and likely to turn on our master at any moment.

Oak thinks of us as sisters, which I can tell makes Oriana nervous, even though I would never do anything to hurt him.

“You are under Madoc’s protection, and he has the favor of the High King,” Oriana says. “I will not see Madoc made to look foolish because of your mistakes.”

With that little speech complete, she walks out toward the horses. One snorts and strikes the ground with a hoof.

Taryn and I share a look and then follow her. Madoc is already seated on the largest of the faerie steeds, an impressive creature with a scar beneath one eye. Its nostrils flare with impatience. It tosses its mane restlessly.

I swing up onto a pale green horse with sharp teeth and a swampy odor. Taryn chooses a rouncy and kicks her heels against its flanks. She takes off like a shot, and I follow, plunging into the night.

Faeries are twilight creatures, and I have become one, too. We rise when the shadows grow long and head to our beds before the sun rises. It is well after midnight when we arrive at the great hill at the Palace of Elfhame. To go inside, we must ride between two trees, an oak and a thorn, and then straight into what appears to be the stone wall of an abandoned folly. I’ve done it hundreds of times, but I flinch anyway. My whole body braces, I grip the reins hard, and my eyes mash shut.

When I open them, I am inside the hill.

We ride on through a cavern, between pillars of roots, over packed earth.

There are dozens of the Folk here, crowding around the entrance to the vast throne room, where Court is being held—long-nosed pixies with tattered wings; elegant, green-skinned ladies in long gowns with goblins holding up their trains; tricksy boggans; laughing foxkin; a boy in an owl mask and a golden headdress; an elderly woman with crows crowding her shoulders; a gaggle of girls with wild roses in their hair; a bark-skinned boy with feathers around his neck; a group of knights all in scarab-green armor. Many I’ve seen before; a few I have spoken with. Too many for my eyes to drink them all in, yet I cannot look away.

I never get tired of this—of the spectacle, of the pageantry. Maybe Oriana isn’t entirely wrong to worry that we might one day get caught up in it, be carried away by it, and forget to take care. I can see why humans succumb to the beautiful nightmare of the Court, why they willingly drown in it.

I know I shouldn’t love it as I do, stolen as I am from the mortal world, my parents murdered. But I love it all the same.

Madoc swings down from his horse. Oriana and Taryn are already off theirs, handing them over to grooms. It’s me they’re waiting for. Madoc reaches out his fingers like he is going to help me, but I hop off the saddle on my own. My leather slippers hit the ground like a slap.

I hope that I look like a knight to him.

Oriana steps forward, probably to remind Taryn and me of all the things she doesn’t want us to do. I don’t give her the chance. Instead, I hook my arm through Taryn’s and hurry along inside. The room is redolent with burning rosemary and crushed herbs. Behind us, I can hear Madoc’s heavy step, but I know where I am going. The first thing we have to do when we get to Court is greet the king.

The High King Eldred sits on his throne in gray robes of state, a heavy golden oak-leaf crown holding down his thin, spun-gold hair. When we bow, he touches our heads lightly with his knobby, be-ringed hands, and then we rise.

His grandmother was Queen Mab, of the House of the Greenbriar. She lived as one of the solitary fey before she began to conquer Faerie with her horned consort and his stag-riders. Because of him, each of Eldred’s six heirs are said to have some animal characteristic, a thing that is not unusual in Faerie but is unusual among the trooping Gentry of the Courts.

The eldest prince, Balekin, and his younger brother, Dain, stand nearby, drinking wine from wooden cups banded in silver. Dain wears breeches that stop at his knees, showing his hooves and deer legs. Balekin wears the greatcoat he favors, with a collar of bear fur. His fingers have a thorn at each knuckle, and thorns ridge his arm, running up under the cuffs of his shirt, visible when he and Dain urge Madoc over.

Oriana curtsies to them. Although Dain and Balekin are standing together, they are often at odds with each other and with their sister Elowyn—so often that the Court is considered to be divided into three warring circles of influence.

Prince Balekin, the firstborn, and his set are known as the Circle of Grackles, for those who enjoy merriment and who scorn anything getting in the way of it. They drink themselves sick and numb themselves with poisonous and delightful powders. His is the wildest circle, although he has always been perfectly composed and sober when speaking with me. I suppose I could throw myself into debauchery and hope to impress them. I’d rather not, though.

Princess Elowyn, the second-born, and her companions have the Circle of Larks. They value art above all else. Several mortals have found favor in her circle, but since I have no real skill with a lute or declaiming, I have no chance of being one of them.

Prince Dain, third-born, leads what’s known as the Circle of Falcons. Knights, warriors, and strategists are in their favor. Madoc, obviously, belongs to this circle. They talk about honor, but what they really care about is power. I am good enough with a blade, knowledgeable in strategy. All I need is a chance to prove myself.

“Go enjoy yourselves,” Madoc tells us. With a look back at the princes, Taryn and I head out into the throng.

The palace of the King of Elfhame has many secret alcoves and hidden corridors, perfect for trysts or assassins or staying out of the way and being really dull at parties. When Taryn and I were little, we would hide under the long banquet tables. But since she determined we were elegant ladies, too big to get our dresses dirty crawling around on the floor, we had to find a better spot. Just past the second landing of stone steps is an area where a large mass of shimmering rock juts out, creating a ledge. Normally, that’s where we settle ourselves to listen to the music and watch all the fun we aren’t supposed to be having.

Tonight, however, Taryn has a different idea. She passes the steps and grabs food off a silver tray—a green apple and a wedge of blue-veined cheese. Not bothering with salt, she takes a bite of each, holding the apple out for me to bite. Oriana thinks we can’t tell the difference between regular fruit and faerie fruit, which blooms a deep gold. Its flesh is red and dense, and the cloying smell of it fills the forests at harvest time.

The apple is crisp and cold in my mouth. We pass it back and forth, sharing down to the core, which I eat in two bites.

Near where I am standing, a tiny faerie girl with a clock of white hair, like that of a dandelion, and a little knife cuts the strap of an ogre’s belt. It’s slick work. A moment later, his sword and pouch are gone, she’s losing herself in the crowd, and I can almost believe it didn’t happen. Until the girl looks back at me.

She winks.

A moment after that, the ogre realizes he was robbed.

“I smell a thief!” he shouts, casting around him, knocking over a tankard of dark brown beer, his warty nose sniffing the air.

Nearby, there’s a commotion—one of the candles flares up in blue crackling flames, sparking loudly and distracting even the ogre. By the time it returns to normal, the white-haired thief is well gone.

With a half smile, I turn back to Taryn, who watches the dancers with longing, oblivious to much else.

“We could take turns,” she proposes. “If you can’t stop, I’ll pull you out. Then you’ll do the same for me.”

My heartbeat speeds at the thought. I look at the throng of revelers, trying to build up the daring of someone who would rob an ogre right under his nose.

Princess Elowyn whirls at the center of a circle of Larks. Her skin is a glittering gold, her hair the deep green of ivy. Beside her, a human boy plays the fiddle. Two more mortals accompany him less skillfully, but more joyfully, on ukuleles. Elowyn’s younger sister Caelia spins nearby, with corn silk hair like her father’s and a crown of flowers in it.

A new ballad begins, and the words drift up to me. “Of all the sons King William had, Prince Jamie was the worst,” they sing. “And what made the sorrow even greater, Prince Jamie was the first.”

I’ve never much liked that song because it reminds me of someone else. Someone who, along with Princess Rhyia, doesn’t appear to be attending tonight. But—oh no. I do see him.

Prince Cardan, sixth-born to the High King Eldred, yet still the absolute worst, strides across the floor toward us.

Valerian, Nicasia, and Locke—his three meanest, fanciest, and most loyal friends—follow him. The crowd parts and hushes, bowing as they pass. Cardan is wearing his usual scowl, accessorized with kohl under

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...