- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

An evocative, literary crime thriller set in Dublin and Spain just before the outbreak of WWII. Christmas 1939. In Europe the Phoney War hides carnage to come. In Ireland Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie keeps tabs on Irishmen joining the British Forces. It's unpleasant work, but when an IRA raid on a military arsenal sends Garda Special Branch in search of guns and explosives, Stefan is soon convinced his boss, Superintendent Terry Gregory, is working for the IRA. At home for Christmas, Stefan is abruptly called to Laragh, an isolated mountain town. A postman has disappeared, believed killed, and Laragh's Guards are hiding something. Stefan is the nearest Special Branch detective, yet is he only there because Gregory wants him out of the way? Laragh is close to the lake where Stefan's wife Maeve drowned years earlier, and when events expose a connection between the missing postman and her death, Stefan realises it wasn't an accident, but murder. And it will be a difficult, dangerous journey where Stefan has to finally confront the ghosts of the past not only in the mountains of Wicklow, but in Spain in the aftermath of its bloody Civil War, before he can return to Dublin to find the truth.

Release date: October 3, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

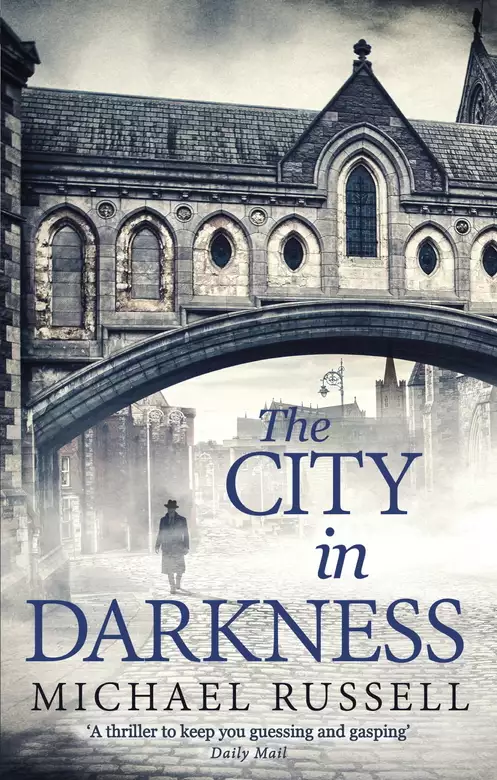

The City in Darkness

Michael Russell

There was barely a whisper of mist on the Upper Lake, a softness in the air where the water rippled among reeds and lapped at the pebble beach at the eastern end. The sun was low in the sky, but the brightness of the morning gave the grey waters an unaccustomed tint of blue. It would be a fine day in the mountains. They rose on either side of the lake, a great amphitheatre folding round it. The tree-lined slopes climbed steeply out of the water, heavy with leaves, a hint of the turning year in the oaks and the yellowing needles of the Scots pines. Higher up heather and bare rock caught the sunlight more keenly. The mountains held the lake tightly on three sides; Camaderry and Turlough Hill to the north and west, Lugduff and Mullacor to the west and south. To the east, through the woods, were the ruins of the thousand-year-old monastery of St Kevin, the Round Tower and the tumbled stones of ancient churches and monastic cells. As morning wore on the buses and cars would come from Dublin to fill the valley with visitors. But for a few hours the only sounds would be the rooks and the chattering sparrows and, somewhere above, the high shriek of a peregrine hunting.

Back from the pebble shore a small green tent was pitched. Beside it were the ashes of a fire from the night before. Inside a woman and a man in their mid-twenties lay close together; between them a boy, not yet three. The man and boy were asleep. The woman lay on her back, looking up at the ridge of the tent. She had not slept well; in all the peace around her, in the slow breathing of her husband and son, and in the morning birdsong outside, she was not at peace. She sat up slowly. Her yellow hair fell over her shoulders. She pushed the blanket away from her and shivered.

She looked at the man and the boy, smiling. Troubled as she was, she felt her contentment; it was deeper and more solid than she had ever anticipated such things could be. What was wrong had nothing to do with this. It was something else and part of her simply wanted to walk away from it. What it would mean for people she cared about, people she had grown up with, was already hard to bear. But she had no choice. What she had discovered, so suddenly, so unexpectedly, could not be ignored. She looked down at her husband again. He would know what to do. He would help her find the strength she needed. And when it was done he would help her leave it behind. Only strong light would clear away the darkness.

She would tell him tonight, at his parents’ farm across the mountains. She needed to be somewhere else to say it. But for now she wanted to fill her head with the new morning. She stretched across to a duffle bag and took a swimming costume, inching down the tent to the flaps, pulling it on with as little movement as possible. The man slowly opened his eyes.

‘What are you doing?’

‘A swim. It’s a beautiful morning.’

‘Jesus, it’ll be cold enough in that water.’

‘I’ve swum in that lake since I was four years old, summer and winter,’ she laughed. ‘My father always said, if you’re cold swim faster!’

‘Have you forgotten the day you begged me to take you away from your mad father and a lifetime’s sentence of healthy exercise?’

She leant forward, her face over his and kissed him. As she did he could smell the scent of her body on her skin from the night before.

‘There are better ways to warm up than swimming, Maeve.’

‘I need to clear my head. Go back to sleep.’

As she got up he saw, momentarily, that her smile had gone.

‘Are you all right?’

‘I need to talk to you, that’s all. When I have, I’ll be grand.’

She smiled once more, then crawled out into the morning. He lay back. There was something wrong. She had been quiet the day before, for no real reason. It was only now it struck him. And last night, as they sat looking at the Upper Lake after making love, she had been tearful for a moment, in a way that was unlike her. Still, it couldn’t be serious. It was only two days ago that she had talked long into the night about her happiness and about their simple, ordinary plans for the future. Stefan yawned, looking across at the face of the sleeping boy. He closed his eyes. He listened to the rooks, a blackbird singing overhead, the rhythmic, easy breathing of his son. And then almost immediately, he was asleep again.

The woman walked through the trees to the lake. She stood, looking up at the mountain slopes that enclosed this space she knew so well. It had seemed a simple idea; driving down from Dublin for a week with his parents at the farm outside Baltinglass; outings in the hired car they couldn’t quite afford; a few quiet days by the Upper Lake where, until her marriage and her son, she had known her happiest times. Now it could never be the same again. Everything would change; everything in her childhood would be different. It could never be the refuge it was. But perhaps there had always been questions. She was already wondering if the happiness she remembered had been real. And what she had discovered had somehow shocked her less than it should have done. It wasn’t that she knew, even remotely, but she felt as if something had opened up in her that she should have sensed. There were uneasy things, uncomfortable things now, crowding in on her. She knew the darkness had been there all along.

‘Shite!’

Her voice echoed back from the mountains. She waded into the water, wanting its coldness to drive it all from her mind. Then she swam. She swam hard, unaware how far she was going, pushing forward, stroke after stroke. She stopped and bobbed up, treading water. She felt the sun, warmer now, higher overhead. She was close to the craggy face below the sheer Spinc on the south side of the lake, where steep steps led up to the cave and the ruins that were called St Kevin’s Bed. She lay on her back, kicking her legs very slowly, letting herself drift on towards the rock.

The legend came back into her head. She remembered the game they played as children. She was Kathleen of the Unholy Blue Eyes, trying to make the saint fall in love and forsake his sacred vows; Kevin and his monks had to chase her from the cave, throwing bunches of stinging nettles at her. In the gang of friends she spent her summers with the boys were Kevin’s monks, the girls Kathleen’s witches, stealing the saint’s gold along with his virtue. The gold had been their own addition to a tale that was really no more than chasing and catching. But as they grew older the price the girls paid for capture turned from dodging the stinging nettles to forfeiting a kiss; it wasn’t quite in accord with the triumph of St Kevin’s sacred celibacy over the wiles of Kathleen and those unholy blue eyes.

She laughed, but somehow it seemed less innocent now; the cave in which those kisses were given felt blacker. She kept on treading water. She had to work it out, every detail of what she would tell her husband. If he didn’t believe her, then who would? It was then that she saw the dinghy.

The boat had pulled out from the landing place below the steps to St Kevin’s Bed. She knew it, old and battered now, the paint bleached and peeling; she knew it when it was new, fifteen years ago. It was the companion of a hundred lake adventures. And she knew the rower. He would have been fishing in the early morning when he had the lake to himself. She watched him row towards her, his back arched over the oars. He looked round, grinning, calling out with the voice of old familiarity.

‘Long time since I caught a mermaid here!’

She smiled, still treading water. He must have seen her swimming towards the rock. But her smile stopped. She had forgotten, just forgotten, what was going to happen. He didn’t know. None of them knew. How could she have an ordinary conversation? How could she laugh, joke, lie?

The man swung the boat round to face her and shipped the oars. She swam up to the boat and grabbed the side. She didn’t know what to say.

‘I thought I’d row over and see was any bacon frying, Maeve.’

‘There’s maybe a cup of tea and some bread and jam,’ she said.

‘They say a woman who puts a plate of bacon in front of her man every day need never fear he’ll wander. A vaguely risqué metaphor trying to get out there, I guess. But anyway, beware of too much bread and jam!’

‘I think we’ll cope, with or without bacon.’

‘Absolutely,’ he said. ‘I’m sure he doesn’t go without.’

She looked at him, more puzzled than offended. It was unfunny in a way she never remembered him being unfunny; it felt unpleasant. Maybe he was trying too hard to make a joke. He grinned the warm, rather empty grin he always did. It had never before occurred to her it was empty, but that’s what it was. There was nothing behind it. And it wasn’t warm, in any way whatsoever; even as the word formed in her head she replaced it with cold.

‘You’re going back today?’

‘To Baltinglass, but Stefan has to be in Dublin on Saturday.’

‘Ah, a policeman’s lot!’

She felt the sneer in his voice.

‘Get in. I’ll row you back across. If it’s only tea and bread and jam, I’ll take what’s going, even if it does sound a bit like a prison breakfast.’

She realized how tired she was. She had swum a long way. She wanted to be with her husband and her son. She wanted to pack up and go.

‘All right, can you pull me in so?’

She started to heave herself up into the boat. He didn’t budge.

‘I do need a hand.’

Her voice was sharper; she was no longer concerned about him. And maybe this was what would happen, she thought. This was the start. No one would come out of it unchanged or undamaged. Where there had been friendship and fond memory there would be guilt, accusation, anger. They would feel they should have known; they’d see faults, weaknesses, dislike.

He was staring at her quizzically, as if he knew what she was thinking. He leant forward, and suddenly his hands were on her, one holding her right arm, the other clasping her hard between her neck and shoulder. And he was pushing her, pushing her down, back into the water.

For a few seconds she thought it was a bad joke. He was strong; he had been even as a boy. She was struggling, fighting to get out of his grip. But his hands held her tightly. He wouldn’t let go. As she thrashed in the water he was still bearing down on her. Her head went under, gasping, choking. All she could try to do was break away, but his grip never faltered.

Water filled her mouth and her nose. She pushed up, desperately trying to hit out. She tried to scream. Her cries barely echoed across the lake. She was already weak. He pushed down again, his arms in the water as she flailed and kicked and struggled. But in all that movement he was still, his eyes fixed on her. And then abruptly she stopped moving. He held her under the water. Strands of her fair hair floated delicately on the swell.

The lake was calm again. Finally, he let go. Her body sank. The last wisps of hair disappeared into the blackness. He gazed down into the depths. She was there, not far beneath the surface, but despite the blue sheen the day had given the water, it was too dark to see her now.

He moved back into the centre of the boat. He put out the oars and pulled back towards the Spinc and St Kevin’s Bed. He felt a sense of satisfaction. It had worked better than he had imagined. He had been watching the tent since the previous afternoon, unsure what she knew, unsure if he was at risk, but knowing he could not let it go. He came closer after dark. He heard the two of them. Fucking. He hadn’t expected that. It was unpleasant to listen to, unpleasant to think about. By morning he knew he must act. He remembered she swam every morning as a child; he thought she would still, as if this place still belonged to her somehow. As for what she did or didn’t know, death resolved all doubt, all risk; that was the simple truth. And it had been so easy, so very easy, that he knew it was meant to be, like so many things in his life. Yet he would remember her more fondly now. In an odd way it was almost as if she had come home.

Jarama, Spain, February 1937

The guns stopped at almost the same time along the valley of low hills on either side of the Jarama River. All day the noise of battle had sounded; the roar and thud of artillery and tanks, the whine of aircraft, the rattle of machine guns, the staccato crack of rifles, and behind that the cries and the screams of men in all the various stages of fighting and killing and dying.

For the fifth day Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s army had flung itself across the muddy, sluggish river at the soldiers of the Spanish Republic, battling its way up over parched earth and cracked stone, through the groves of shrapnel-splintered olives, over the bodies of the five days’ dead. If the road through the valley was taken, Madrid would fall, and what remained of the hated Republic would be pushed into the Mediterranean.

Each day the Republic’s line bent beneath the Nationalist onslaught. Hilltop positions were taken, held, lost, retaken, lost again. Each day that line held only by virtue of those who died to hold it. And each evening as the sun set, and the guns were quiet, and the sour smell of cordite faded, the last heat of the day filled the air with the smell of the decomposing dead. In the silence the engine-like buzz of millions of flies was a solid bass to the chattering cicadas. Along the Jarama the crows swarmed in black clouds for the carrion; the buzzards that had circled overhead all day sailed down to feed. Here and there a soldier fired a shot to chase the birds from the feast; sometimes a shallow trench was dug to keep the bodies whole. But there were always too many bodies, and there would only be more tomorrow.

On the bare brow the men of the Fifteenth International Brigade had christened Suicide Hill that day, an Irishman looked down at the river, smoking a thin, hand-rolled cigarette. He wore the uniform of a brigadier of the Spanish Republic’s International Brigades. The men he commanded had come to Spain to fight for a collection of ideals that didn’t always make easy bedfellows. They were big ideas: freedom, democracy, justice, socialism, communism. But what mattered was a common enemy. Here it was Franco’s fascism, but that was no different to Mussolini’s fascism; no different, above all, to Hitler’s fascism. That was what united the 400 Englishmen and Irishmen who had marched to the hills above the Jarama River that morning; less than 150 were still alive.

Brigadier Frank Ryan watched a dozen of his men move among the bodies on the hillside, collecting guns and ammunition. On the Nationalist side the dead wore the desert fatigues of the Spanish Foreign Legion, the bright red fezzes and cloaks of the Moroccan infantry, the grey-green of the Falangist militia. The Republican dead mostly wore the tan-brown overalls of the International Brigades; their names were in Ryan’s head, above all the names of the dead Irishmen he had led up Suicide Hill that day. Men he came from Ireland to Spain with. Men he had campaigned for Irish freedom with in the streets of Dublin. Men he had fought beside in the IRA in the Tipperary hills. He dropped his cigarette end and started to roll another.

From the olive grove behind came the sound of shovels hitting stony soil; trenches were being deepened. There was a smell of cooking; from pots of vegetable stew the scent of herbs someone had found, that smelt not of death and ideals but of being alive. There was laughter rising up out of words about nothing. It mattered that his men could laugh. Even staring at the dead he needed them to laugh, scream, cry, anything that had life in it. He heard his officers moving through the lines, making the lists that would soon come to him. The lists of the living; the longer lists of the dead.

On the farm track behind the olive grove a truck backfired. Frank Ryan looked round. On the canvas of the battered vehicle were the words ‘Comisaría Política’, on the cab roof a trumpet-like loud speaker. The distorted martial tones of the ‘Internationale’ blasted out. A voice crackled, enthusiastic, purposeful. The language was English, though the same words had been heard along the line in Spanish, French, German. They were words that few wanted when the bodies of their friends were still warm.

‘Comrades, today’s victory has pushed back the fascists again! A triumph for the people of Spain! The workers of Spain give thanks to the men of the International Brigades who stand shoulder to shoulder in the struggle. Where the people are united, we are invincible! No pasarán!’

Some dutiful comrades raised weary clenched fists and shouted ‘No pasarán!’ The ‘Internationale’ started up again and the truck disappeared.

Brigadier Ryan took the sheets of paper that had been handed to him by the young English lieutenant. He didn’t bother to look at them.

‘How many, Allen?’

‘Two hundred and twenty dead. Thirty seriously wounded.’

‘Jesus, we can’t hold this place with a hundred men.’

Frank Ryan finally looked at the names. He was a thin man, with sharp features. His face was lined; he seemed older than his thirty-five years. It was a face that was good at showing passion and enthusiasm, but not much else. It was no bad time not to show much. The men of the Fifteenth Brigade were watching; even for those who had been in the thickest of the fighting the cost of retaking Suicide Hill was only just sinking in. It wasn’t Brigadier Ryan’s business to show what he felt now; it was to prepare for the attack they all knew would come the next day.

‘We’d better get to Brigade HQ. I’ll shout, you beg. Now Commissar Klein has congratulated us, they need to know the price. No reinforcements, then Klein needn’t come back tomorrow. We’ll be feeding the crows too.’

Brigadier Frank Ryan and Lieutenant Allen Armstrong left Brigade HQ. What they brought away was only the vaguest possibility of reinforcements from the stretched French and Belgian battalion, and the boot and back seat of their commandeered Renault filled with bottles of red wine and brandy. It was the best HQ could offer. Well, wasn’t there something to celebrate in the miracle of Suicide Hill? In the small white finca, surrounded by a thousand olive trees, Ryan had indeed shouted, cajoled and begged for reinforcements. The result had been yet more achingly sincere congratulations from Spanish officers and the International Brigades’ political commissariat, still barely able to believe the line had resisted the Nationalist onslaught. The men of the Fifteenth Brigade, now dead for the most part, were the heroes of the hour. But the expectation that they could repeat what they had done tomorrow was a hope that trumped arithmetic. There would be no more troops. The Fifteenth Brigade’s survivors would have to hold their line.

It was dark as the Renault rejoined the road along the eastern ridge of the Jarama Valley. The road was busy; columns of soldiers walking with the slow tread of men who had fought all day and would fight again with the daylight; trucks carrying ammunition and pulling artillery; carts ferrying the wounded and the dead. And while Frank Ryan chain-smoked, Allen Armstrong hunched over the wheel, weaving through the melee of men and vehicles, trying to avoid the potholes and craters that the traffic of war and constant shelling had created. Then suddenly he swerved off to the right.

‘I’ll take the road towards Belchite. We’ll be half the night here.’

The car headed downhill on a track that ran close to the river and the front line before climbing up to the escarpment where the Fifteenth Brigade was camped. There were a few straggling soldiers, small camps and gun positions. But it was surprisingly quiet. With the light of the moon in the sky, Ryan found himself thinking of the winding roads of the west of Ireland at night. It didn’t feel so different. He believed the war he was fighting here was the same war he had fought there. But the uneasiness that took him out of Ireland was never far away, even now, like an itch beneath beliefs that should have been as comfortable as old clothes. Fighting was fine if you didn’t stop to think. But the silence had made him think of home. He felt as if he wanted to stay on that quiet road for a long time.

Rounding a bend, Armstrong’s foot hit the brake. They lurched forward; the Renault skidded. Something dark thudded against the bonnet.

‘You all right, Frank?’

‘Apart from my head. I hit the fucking—’

‘That’s all right, we all know how hard your head is – sir.’

Frank Ryan got out. As the lieutenant did the same he unbuttoned the clip that held his revolver. A few yards away lay a man in uniform. Ryan crouched down. Armstrong pushed the pistol back into its holster and shone a torch on to the soldier’s face; it was stained with sweat and dirt and dried blood. The uniform that could have been grey or khaki or green was filthy and shredded; one sleeve was black, hardened with the same dried blood. It was a very young face; the soldier looked like he was still in his teens.

‘Is he alive?’ asked Lieutenant Armstrong.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph!’ The soldier gritted his teeth in pain.

Frank Ryan laughed. The accent, like the words, was unmistakable.

‘Is he one of ours then?’ Armstrong bent down.

A look of relief pushed away the pain in the soldier’s face.

‘I never thought I’d make it. I was hiding, running, hiding.’ He tried to sit up. There were tears now. He was coughing. ‘I didn’t even know where I was half the time. Jesus, weren’t they all round me, everywhere?’

‘What’s your company?’ Ryan asked.

‘I got hit when they started firing. I ran, I must’ve passed out. I took a bullet. We were cheering them on, then they fired, our own fucking side—’

Armstrong produced a canteen of water. The soldier drank thirstily. Frank Ryan watched him, frowning; there was something odd about him.

‘Who’s your sergeant, who are your officers?’

‘Tommy O’Toole, sir. I think he was killed.’ He crossed himself. ‘He went down in front of me. When we marched over the river they thought the Bandera was Brigaders! The feckers wouldn’t stop shooting at us!’

The last word, Bandera, left no doubt in Brigadier Ryan’s mind.

‘Christ!’ he said quietly.

The Englishman nodded; there wasn’t anything else to add.

Ryan shone the torch closer to the torn uniform. The grey-green colour was clear now. Something glittered on the collar, a small silver harp, an Irish harp. The young soldier was one of the men General Eoin O’Duffy had brought from Ireland to fight for Holy Spain and Holy Ireland against communism, atheism and darkness. They had come with the blessings of the Church in their ears, with rosaries and holy water, and all the saints in heaven looking down on their crusade. But the Irish Bandera had not lived up to its high ideals. O’Duffy’s men, stronger on drinking, whoring and praying behind the lines than fighting, were an embarrassment even to Franco. Yet there were uneasy rumours that the fascists wanted to push their own Irish troops against the Irish Brigadistas. Despite the contempt for the Bandera on the Republican side, the Connolly Column soldiers knew there were old IRA men in their ranks, men they knew, men they fought beside against the Black and Tans, against the Free State in the Civil War.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Private Mikey Hagan, sir.’

He saluted; he was trying to get up, shaky, still in pain.

‘You need to look at my uniform, Mikey,’ said Ryan.

The boy soldier frowned, not grasping what this meant.

‘You’re a prisoner. My name is Frank Ryan. I am a brigadier in the Fifteenth International Brigade. I’m sorry, you didn’t make it back.’

The fear in Hagan’s eyes was momentary. He was too tired not to feel this Irishman whose name he knew offered safety.

‘I know you Mr Ryan, Brigadier Ryan. You’d know my father, Liam Hagan. He’s a teacher, in Cashel. He was with you in the Galtee Mountains, in twenty-two it was, fighting the Free State. He always talks about you.’

He spoke as if they were somewhere else; a railway platform, a pub. He looked at the man whose prisoner he was with pride in the connection.

‘And your father’d be pleased you’re here, would he?’

‘And why wouldn’t he be when we’re fighting God’s war?’

The words were defiant. Then a deeper spasm of pain wracked Mikey Hagan, spreading from his arm into his body. He was unconscious.

‘Get him into the car, Allen.’

They pulled open the back door; Armstrong shoved aside crates of wine and brandy. They pushed the Bandera private into the seat.

‘The Sanidad Militar can sort him out. It’s all we can do.’

‘Or we could shoot him.’

‘Is that supposed to be funny?’

‘The Field Police will hand him to the Comisaría Política. When the party hacks have interrogated him, for sod all I’d say – they’ll shoot him.’

Ryan said nothing; it was true.

‘Still, all’s fair,’ continued the Englishman, ‘and if the fascists got hold of us, well, they’d shoot us, so, quid pro quo! Buyer beware, etc.’

‘We’ve our own men to keep alive, Allen.’

Lieutenant Armstrong looked at the young face through the car window. He looked at the night sky, conscious of the rare silence. There was no reason for what he was saying. It shouldn’t matter. But there was more and more that didn’t matter. It was arbitrary that this did, but it did.

‘When you’ve just seen a dozen of your best friends die, having another man shot for no reason, even in the wrong uniform – pisses me off. That’s all. It pisses me off.’ He grinned. ‘And you did know his father.’

‘I never knew his father, for Christ’s sake. What the fuck are those O’Duffy bastards doing here? It’s Eoin O’Duffy who wants shooting. He doesn’t give a shite about Spain, any more than the priests who sprinkled holy water over his men. All he wants is to go home a sainted hero. And there’s his fucking martyr.’ He looked at Mikey Hagan’s unconscious face pressed against the glass. ‘God, Ireland can produce some gobshites!’

‘We’ll pass the turn for Belchite,’ said Armstrong. ‘A kilometre from the Jarama. One of the Canadians said there’s a doctor there. He could be patched up and pointed across the river. More chance than we can offer.’

‘And what about the Republicans in Belchite?’

‘He’s just one of Frank Ryan’s Irishmen with a bullet in his arm.’

‘Fuck you, Lieutenant.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘Let’s get him out of that uniform. And get a bottle of brandy.’

They opened the car door. As Mikey Hagan fell out, Ryan caught him. He started to unbutton the grey-green jacket. He turned to Armstrong.

‘The brandy.’

‘He’s still unconscious. It’ll choke him.’

‘Did I say it was for him?’

The moonlight picked out the road into Belchite. There were patches of open ground and groves of olives and walnuts. Fires burned where Republican machine guns pointed towards the Nationalist lines. At the sentry posts, as Frank Ryan wound down the window and shouted out his name, they were waved through with the raised fists of the struggle. The militia men knew Brigadier Ryan. The story of Suicide Hill had swept along the line faster than Hermann Klein’s propaganda truck. The thin Irishman and the men of the Fifteenth Brigade needed no papers or permits here.

In the town the battle that had pushed Belchite back and forward between the Republicans and the Nationalists all week had left its scars in the broken buildings and the pockmarked plaza. A fire, fuelled with the timber from damaged ho. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...