- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

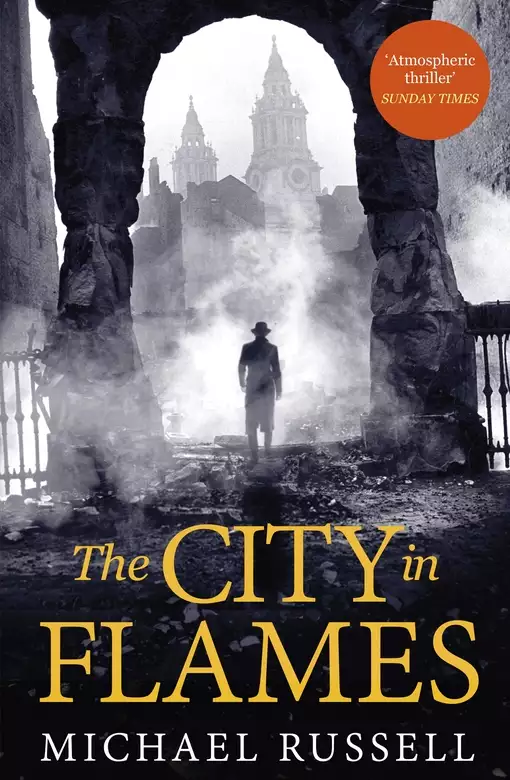

1940. A woman lands on the Scottish coast from a German flying boat and goes to ground, hunted by British Intelligence. Suspended from the Irish police for reasons he won't explain, Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie is working on his father's farm in Wicklow. One day he vanishes, leaving no sign of where he is heading - or why. Even in rural Ireland, rumours of assassination and Nazi spies fill the air, leaving Stefan's father to wonder whether he is in terrible danger. Meanwhile in London, Stefan is undercover, working in a pub: The Bedford Arms in Camden. Run by an alcoholic, bankrupt landlord, it's a wartime refuge for the Irish in London. And while the city shakes under the Blitz, Stefan falls into a romance with Vera Kennedy, an Irishwoman who has her own dark secrets to hide. But behind closed doors, a different war is being fought, and Stefan has more work than pulling pints on his hands. The Bedford Arms hides some unexpected dangers. The drunken landlord is not as witless as he seems, and Stefan's mission is under perilous threat. When Vera disappears, he discovers that the Nazis were far closer to home than he thought. As he embarks on a journey to trace Vera from London to Ireland, Stefan will have to decide where his true loyalties lie. Praise for Michael Russell 'Complex but compelling . . . utterly vivid and convincing' Independent on Sunday 'A superb, atmospheric thriller' Irish Independent 'A thriller to keep you guessing and gasping' Daily Mail 'Atmospheric' Sunday Times

Release date: July 4, 2019

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 313

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The City in Flames

Michael Russell

In Germany and Britain Irish neutrality was viewed in different ways. In Berlin it was seen as a huge blow to the British. When Britain was invaded, it was thought, Ireland would not only become a base for rearguard attacks, the Irish government would reveal its true support for Germany and join in. The Germans seemed blind to the fact that de Valera’s hostility to England did not translate into any kind of enthusiasm for Nazi Germany. There were Germans who wanted to use Ireland more effectively, however. By supplying arms to the IRA, they aimed at mounting sabotage operations against the British and even starting an uprising in Northern Ireland that might drag de Valera into the war on Germany’s side. The IRA, believing that England’s difficulty was Ireland’s opportunity, as always, awaited German help and German victory. Britain regarded Ireland’s neutrality with a grudging acceptance, but some felt it was a betrayal that could not be tolerated. In 1940 Winston Churchill came close to agreeing to the invasion of Ireland. The Irish government had very good reason to believe that both the British and the Germans were preparing plans to invade the country. And there were people who wanted to put those plans into operation … one way or another.

Wicklow, 1921

David Gillespie felt the hard stone of the floor first, and it was all he felt. The stone flag was cold, and for a moment that coldness was a kind of comfort against his cheek. He didn’t know why it seemed a place to stay in, but it was somehow soothing; it held the weight of his head, as if it was fixed. He couldn’t move and he didn’t want to. For some seconds that was all he was aware of: a dark, enfolding dream he was struggling not to wake from. Then the pain shot through his jaw, sharp, hot, and he pushed himself up. He opened his eyes and saw only a blur of yellow light. He tasted vomit in his mouth and the iron tang of blood. He had been unconscious for barely a minute. Now, as he sat up on the stone floor, he knew where he was again. The blow had come from a rifle butt. It followed a series of punches to his stomach and face. They had got heavier as the tempers of his interrogators had turned from amusement to anger.

‘Davie, am I getting through to you yet, you fucker?’

In David’s eyes the blurred light sharpened then diminished. It was an oil lamp, sitting on a table above him. Over it was the face of the man who had just spoken, round and red, sweating. David stared up, unmoving, trying to focus. He saw the sweat more clearly than he saw the face. It was glinting in the light.

‘Get him up.’ The voice was Scottish, maybe Glasgow. It was an odd thought, but David had tried to identify where the interrogator came from since the start, where they all came from. He had Scotland; London for another; then Leeds, Yorkshire anyway. It was a way to harden his mind, to distance himself from what was happening. He had to ride this out until they got fed up with it.

The man turned to the table. He picked up a bottle and drank.

Hands clutched David on either side and pulled him up, dragging him backwards and pushing him down on a chair. The pain pierced him again, from his jaw upwards, into his head, stabbing, sawing. There were two uniformed men standing on either side of him. A fourth sat on a chair close by, smoking a cigarette, the rifle that had smashed into David’s face lying across his lap. Four Black and Tans. There had been more at the start. They all wore, in various combinations, the black and brown tunics and trousers that gave them their name. There was silence in the room now. The man who had spoken bent to take bottles of beer from a crate on the floor. He walked a slow circle, handing them to the other Black and Tans. It was a lull anyway; the anger was on hold. None of them looked at him. They didn’t speak to each other; they just drank. Only minutes ago the room was full of their fury, full of blows, full of shouting.

David Gillespie reoriented himself to the room. Several oil lamps lit it, but it was big and high. There was darkness above; the light around him and his interrogators disappeared into black corners. It smelled of dust and stone and stale urine. It was empty apart from a scattering of old and new debris: broken, wood-wormed benches and pieces of rusting iron that had once belonged to bedsteads; bottles and tin cans made up the midden of the present occupants. Although he had never been in this place before, he did know it. The Black and Tans had brought him from the square in Baltinglass, out of the town, to the derelict Workhouse where they were barracked. And at the back of the Workhouse was the Fever Hospital, set apart from the other buildings so that the weak and emaciated inmates of the Workhouse could be taken away to die, not so long ago, when cholera and typhus beat their way into the overcrowding and the filth. Then it had been evidence that even amidst the most carefully structured degradation and misery, things could still get worse. But if that brutality had gone, another now replaced it: the brutality of war. David Gillespie had not anticipated what would happen that night. He knew he should have done. He had fled that brutality before; he had believed it was all he needed to do. He had ignored how arbitrary it was, how capricious. He sat in the Fever Hospital now, watching the Black and Tans drink. He knew it wasn’t over. The man who had spoken turned back to him, still sweating, smiling.

‘Why are you Irish such cunts, even when you’re on our fucking side?’

At the end of the main street in Baltinglass, where the road broadens and the buildings spread out on either side and a triangle is formed by a terraced row of houses and the white courthouse behind them, there is a statue of a man with a musket at his side. He is Sam McAllister. When the 1798 rebellion against the British collapsed and the last whispers of the struggle were being fought out in the mountains above Baltinglass, McAllister died to save his commander, Michael Dwyer, and allow him to live and fight a little longer. The statue had been erected in 1904 to commemorate 1798, in the name of the people of Wicklow, though by no means everyone who gazed on Sam McAllister and his musket shared that sentiment. The people of Wicklow had killed each other in considerable numbers in 1798, and when the statue went up it surprised many that it was not Michael Dwyer, the hero, who stood at the centre of the Triangle, but his lieutenant, who had the advantage of coming from the other end of Ireland. He was remembered for his bravery and self-sacrifice, not for killing anybody’s ancestors, and he carried no list of his own relatives, executed and murdered by their neighbours. He became, within a few years, part of Baltinglass. Even for those who, had they referred to Sam McAllister at all, might have called him just another Fenian bastard, he had somehow become their own Fenian bastard. And when, in 1921, a group of drunken Black and Tans decided to destroy the statue, the response was not what they expected.

The Black and Tans were stationed in Baltinglass, as everywhere else, to deliver the kind of reprisals in the war for Ireland that it was unreasonable, even tasteless, to ask of regular troops, let alone the Royal Irish Constabulary, who suffered, despite everything, from the disability of being uncomfortably Irish. The Tans had no such problems. They were ill-disciplined irregulars who had been given clear assurances that they would not be held accountable for their actions. Even in Wicklow, with its high proportion of Protestants and loyalists, everyone knew they were another mistake in a long list of British mistakes.

The Tans weren’t about to kill anyone that night in the Triangle, as a dozen or so stumbled across Main Street from Sheridan’s Bar. Two of them used the iron railing round the plinth of the statue to clamber up to the top. Others hacked at Sam McAllister with their rifle butts. They were shouting, singing, laughing, clapping. People were coming out from the pubs and houses now. They said nothing; they simply watched. Whether they took a side in the war or tried not to, all they wanted was for this to stop. They wanted these men to leave them alone. And as David Gillespie wheeled his bicycle along the street, that was what he heard in the silence. The Tans heard nothing. It was an audience, no matter who was there to applaud, who was there to be taught a lesson. They were enjoying themselves. One Tan pushed his way through the ring of his comrades, bringing a sledgehammer from the armoured car outside Sheridan’s. He was roared on as he smashed it down on McAllister’s right leg.

It wasn’t David Gillespie’s business to tell the Black and Tans to stop. He had been at the market earlier, looking for a new bull and finding nothing he liked for the money he had. It wasn’t often that he drank, but he stayed in the bar of the Bridge Hotel later than was good for him. It wasn’t long since he had left Dublin, and the life of a farmer that he returned to, for the first time since his teenage years, didn’t sit as easily on him as he claimed. He had been a policeman too long. It had been taken away from him, and he still resented that. And now, as he walked towards the Triangle, heading home, there was more of it. More of what had forced him out of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Whether it was one side or the other, there was always more of it. But none of it was his business. If people wanted it to stop, any of it to stop, it was up to them. The business of his life, since resigning from the Dublin Metropolitan Police and bringing his family back to the farm below Kilranelagh, had been to stand outside it all. He asked only that. He had no reason not to walk past it now.

‘They haven’t paid for half what they drank. They never do.’ It was Johnny Sheridan who spoke, quietly, sourly, standing in the entrance to his bar. ‘Now they may break up the town. And will we ever see a policeman? They’ll be shut away in the barracks right now, waiting for it all to pass them by.’

‘Aren’t we all waiting for that?’ Another quiet voice.

‘Wouldn’t they listen to you, David?’ Johnny was looking straight at David Gillespie, whose progress had been blocked by the press of people.

‘Why would they do that, Johnny?’

There was a great crack as the sledgehammer hit the statue again and the leg splintered. At the same time a shot rang out, to another roar of applause, and the tip of Sam McAllister’s musket flew into the street below. The murmuring in the crowd was louder now. People were pressing forward. Someone shouted.

‘Would you piss off back where you came from!’

The Black and Tans round the statue took no notice. The sledgehammer rose and fell again. But outside Sheridan’s the two men in the armoured car looked uneasy. They had expected acclaim, from some at least, but they could feel the anger that was growing. There were more people now. Men and women; children, too. David looked across at the armoured car as one of the Tans climbed from the front seat into the back. He had just picked up a rifle.

David pushed his bicycle forward. He only wanted to go home.

‘Someone has to tell them to stop.’ It was Johnny Sheridan again.

The people David was trying to push past were looking at him. There was no real reason why they should be. It was a response to Johnny’s words. David was a policeman, a sergeant. At least he had been. And there had been a time, not that long ago, when he was highly regarded. Word was that he was so well thought of in the DMP, that they might even have made an inspector of him.

‘Go home and leave them to it. What’s the point?’ David Gillespie addressed the words to no one in particular.

‘You’d know what to say to them, Mr Gillespie!’

It was a woman’s voice, and as she spoke he saw Johnny Sheridan’s wife ushering her children back through the pub door. The roaring and laughing of the Tans continued. One of them, at least, had realised the mood in the street, looking down from Sam McAllister’s shoulders, waving his rifle over his head.

‘We’ll destroy the cunt! Do you like that, you fuckers, do you?’

‘Let them alone,’ David said. ‘They don’t care what they do.’

‘You’re the one they’ll listen to.’ It was still Johnny’s persistent, quiet voice, but it was joined and echoed by the crowd that was now pulling closer.

‘Sure, weren’t you one of them yourself?’

The words were thrown at him from further down the street. They were met with harsh murmurs of disapproval, but not from everyone. He could feel the expectation. He would do something. He could do something. If he walked away it was no longer about minding his own business, it would turn into a kind of acquiescence. And his instincts were still, despite everything, those of a policeman. If there was trouble, if it went that way, the Black and Tans would do as they pleased. They wouldn’t hold back. Maybe he could calm things.

‘For fuck’s sake.’ David shoved his bicycle at Jimmy. ‘You may hold it.’

He walked towards the armoured car and looked at the driver.

‘Is there an officer here?’

The driver grinned and pointed towards the statue.

‘He’s the one on top, mate.’

David continued across the street. Several of the Black and Tans, growing tired of what they were doing, watched him. He stood in front of them, saying nothing, looking at the man who was climbing down from Sam McAllister’s shoulders. The sledgehammer struck once more. As it did, the man wielding it lost his grip. It hit the cobbles and flew across them towards David. There was more laughter as three Tans scrambled to pick it up, fighting over who would use it next. One of them stood up with his prize, looking at David Gillespie.

‘What the fuck do you want, then?’

‘To speak to your officer.’

The man looked at him, frowning, puzzled by the quiet tone.

‘Are you an officer today, Ernie? There’s a feller wants to talk to you.’

The solitary figure in the Triangle had their attention. The attack on the statue paused. There was some sniggering and laughing. It could be new sport.

The man who had climbed down from Sam McAllister’s shoulders stepped towards David, grinning broadly, with a wink to the man holding the sledgehammer. They were all young, but he was younger, in his early twenties. He was English, blond haired, fresh faced. His accent said well educated.

‘And how can we help you, sir?’

There was more laughter from the young Englishman’s men.

‘People would like you to stop. That’s all.’

‘I see. And you speak for them, do you?’

‘You’ve had your fun.’

‘Do you think we’re here for fun?’ The Englishman’s tone changed.

‘Whatever you’re here for, this won’t help.’

‘So, who the fuck are you? Whose side are you on?’

‘It doesn’t matter where people stand. They don’t want this.’

‘I asked you a question. Who are you?’

‘Does it matter? I live here.’

A short, dark Tan walked forward, cradling a rifle.

‘His name’s Gillespie. He was a DMP man. One of the RIC fellers said.’

‘Dublin Metropolitan Police, eh!’ The officer spoke. ‘Bit off your beat?’

‘Story is he walked out on them,’ said the short Tan. ‘Couldn’t take it.’

There was silence in the Black and Tan ranks now.

‘I see,’ continued the young Englishman. ‘The middle of a fucking war, and he says, “That’s not for me, lads, good luck to you!” A very poor show.’ He turned back to David. ‘Wouldn’t you say that was a poor show, Mr Gillespie?’

David said nothing. Nothing would help until this was finished.

‘But you’ll be well informed, I’m sure. Are you well informed?’

David had to answer. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘What I mean is, we have in you a capital asset, an ex-policeman with all the local knowledge we lack. You’ll know who everyone is. You’ll know where they sit, loyal and not loyal. You’ll know the Fenians who like to keep it quiet. You’ll know what side everyone is on. So what side are you on, Mr Gillespie?’

‘I’m not on any side.’

‘A neutral, by all that’s holy! A neutral! You know what I think of that?’

He walked closer. His face was inches from David’s face. He spat.

‘No neutrals, you cunt. No room for them, old man.’

The officer turned to his men.

‘Bring him back. He’s a spokesman! Let’s hear what he’s got to say.’

The Englishman walked towards the armoured car. His men followed him, forgetting the statue as easily and as idly as they had attacked it. Two of them grabbed David Gillespie’s arms; another covered him with a rifle. As he was marched away, he made no attempt to resist. Outside Sheridan’s the crowd watched and Johnny Sheridan still held the bicycle that David had left behind.

The beating didn’t start straight away. There were a few kicks as David Gillespie was dragged from the armoured car into the Fever Hospital, but only questions followed. Questions about why he had left the Dublin Metropolitan Police; about what he was doing now; about his wife and his son; about who he knew, who he drank with, who was Protestant and who was Catholic. There were empty, meaningless questions he answered simply enough. There were questions about the DMP he didn’t even begin to answer. He said he had left because he didn’t want to do it any more, because the farm at Kilranelagh was a better place for his family. He was happy to be called a coward, a traitor. The weaker he seemed the less he would matter. But the questions they came back to were about what he knew now, the politics of his friends and his neighbours.

Everywhere they went, the Black and Tans quickly ran out of targets, at least among those who didn’t shoot back. They knew the Irish nationalists who were fighting with the Volunteers. They knew the anti-British politicians, hard and soft, in plain sight or on the run. But when it came to the network of secret support that was everywhere, they knew barely anything. Yet that was where terror and intimidation had to be directed; not at the real Republicans, but at the half-convinced, half-afraid, half-baked, fair-weather nationalists who made up most of the population. Without them the hard core were nothing. The rest needed to know their bodies could as easily end up in a ditch as the Volunteers they pandered to. But about all that David Gillespie claimed profound ignorance.

It seemed he never talked politics with anybody. For a man who grew up in the Church of Ireland in Baltinglass, he barely knew a Protestant from a Catholic, let alone the degrees of Republicanism, nationalism or loyalism his neighbours practised. He had nothing to say, except that he had been away too long to know. The young Black and Tan officer became bored very quickly. He took a bottle of whiskey back to the Workhouse and left it to his men to beat something out of the ex-policeman. By that stage he had no interest in whether it was anything useful, but there was a point to be made. Too many Irish people thought they didn’t have to take a side, and that amounted to taking the wrong side. If David Gillespie’s beating provided no information, it would at least be a lesson.

In the darkness of the Fever Hospital ward, the Scottish Black and Tan sat on the edge of the table, looking down at David. He was drinking whiskey. He had lost any notion of what questions he should be asking now. He had asked them too many times. The questions didn’t matter anyway. He didn’t make much distinction between one kind of Irishman and another. None of them could be trusted. They might all hate each other, one tribe and another, but they hated everyone else more. Why anyone thought the fucking shitehole was worth fighting over at all was a mystery. The only Irishmen he respected were the ones who had the guts to fire a rifle. He had killed a few of them and most had died well, even when they were dragged out of bed and stuck against a wall.

The Scotsman stood and walked to the chair propping up David.

‘I’m sorry to say I think you’ve broken your jaw.’

David stared at him. The man’s tone was almost gentle for a moment.

‘That can be a nasty business, painful, eh?’

He leant forward and clasped David’s jaw. He jerked it sideways. It was impossible for David not to let out a scream of pain. The two men who stood on either side held him pushed him down on to the chair. He screamed again as his jaw was wrenched back the other way. The Scot let go and stepped away.

‘Aye, broken; I’d definitely say that’s the problem.’

He took out a cigarette and lit it.

‘You’ll want to be careful you don’t break anything else, Davie.’

David held his head as stiffly as he could. Any movement was agony.

‘You fucked off my boss, you know that? Myself, I’m not unimpressed. Nothing to say about anybody. Why do you think it matters? You could have given us any old shite, you know that. Any old shite about anyone. We don’t care. And you know what? We’ll let everyone know you’re an informer anyway. When we’ve finished, you may expect a call from the Volunteers one dark night. You know what they say, Davie. Once a peeler, always a peeler.’

The Scotsman was angrier than he wanted to show his men. There was a look on David Gillespie’s face, behind the blood and the bruises. It was contempt. The other Tans couldn’t see it, but the Scot did. The young Englishman had seen it too and had felt the same anger. The look was still there.

‘Why waste bullets? When your Republican boyos will shoot you for us?’

The Scot kicked the chair from under David, and again David’s face hit the floor. Again, he screamed as shards of bones ground together and pain stabbed into him. Again, he wanted to sink into the cold stone. He lay for a long moment, unmoving. They were talking quietly now. There was laughter, but that was quieter too. There was movement around him. A chair scraped the floor. The lights were moving. As his mind swam into some kind of focus he thought they were leaving. Suddenly it was very dark. A heavy door slammed. He could feel the tears on his face, through the pain. He was crying, silently.

Berlin, 1940

A thin, pale man gazed out of the upper window of a building on the edge of the great park that was Berlin’s Tiergarten. He looked down at the tree-lined banks of the Landwehr Canal from a room full of people. He was there because it was expected of him. The deafness that had been growing slowly in his head for a long time made such gatherings difficult. The buzz of conversation was a blur of sound, awkward and uncomfortable, but his distance from what was happening went deeper. Wherever he was in Berlin, isolation enfolded him.

Marked by no more than a brass plate that stated its address, 76/78 Tirpitzuferstrasse formed the unassuming boundary of a complex of buildings that stretched back towards the Tiergarten, making up the High Command of the German Armed Forces, the OKW. The offices on Tirpitzuferstrasse looked out on the city’s inner suburbs and breathed the calm air that was the Landwehr Canal’s corridor of trees and moving water. It was one of the most visible of the OKW buildings, and one of the least visited. It consisted of little more than a few floors of narrow corridors and cramped offices. The buildings that contained the machinery of military command spread into the Tiergarten, but 76/78 Tirpitzuferstrasse was almost shut off from them; unless asked, few people from Army Command entered the domain of the Abwehr, Germany’s Military Intelligence arm, jealously commanded by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris.

The man looking out of the window on a bright autumn afternoon in 1940 was an occasional visitor to Tirpitzuferstrasse. He was an Irishman who lectured Abwehr agents, about to be sent to Ireland, on the overlapping, contradictory visions of Irish history, rebellion and unity that the Irish government and its declared enemy, the IRA, shared and fought over. Frank Ryan had left Ireland to fight fascism in the Spanish Civil War, to fight an army financed and supplied by Adolf Hitler. Captured in 1938, he spent two years of torture, mock-execution and sickness in one of Franco’s gaols. He was released into the hands of the Abwehr and taken to Germany. No one else wanted him, including his own country. To survive, he had to turn to a regime he despised. The Abwehr had been persuaded, by Ryan’s German friends, that he was a valuable asset, an ex-IRA man who could bring the warring factions of Irish Republicanism together to support Germany against Britain. He had believed the Germans would let him return to Ireland. Instead, he lived under an assumed name in Berlin, protected by Admiral Canaris’s men but watched by the Gestapo, which had a more accurate understanding of what went on inside the head of this ex-anti-fascist than his Abwehr minders. If Frank Ryan, or Frank Richards as he was known in Berlin, ceased to be useful enough to warrant the protection the Abwehr afforded him, the Gestapo was always there, waiting.

‘You just need to send them on their way with a smile, Frank.’

The German who now stood at the window with Ryan wore the uniform of the Brandenburgers, the Abwehr’s Special Forces battalion. Helmut Clissman was an old friend. The two men had known one another in Ireland before the war. It was Clissman’s plan that rescued Ryan from death in a Spanish prison.

They spoke in English.

‘If I could go with them, I’d smile a bit more, Helmut.’

‘Me too,’ said Clissman. He poured Sekt from a bottle into the empty glass Frank Ryan was holding. ‘Let’s drink to that – to Ireland – someday soon.’

The Irishman raised his glass. ‘Sláinte. Let’s leave it at that. I’ve stopped counting chickens. I’ve seen too many throttled. But you’re going back to Copenhagen tomorrow. Isn’t that easy enough? Good beer and no bombing.’

‘It could be worse.’ Clissman spoke slowly; it could be better too. ‘The bombing’s not so bad in Berlin, is it? Nothing compared to London, they say. We’re too far away.’

‘I’m sure it’s grand. Every day the tobacconist tells me the British are beaten. I don’t know how many days that is. How many days in six months?’

Clissman shot a warning glance at his friend. Ryan hunched his shoulders. He stubbed out his cigarette and embarked on the process of making another with a paper and tobacco. Making the cigarettes meant as much as smoking them. It occupied him when he didn’t want to speak, which was often.

The two men turned back into the room. A dozen people talked in small groups. They were all men, apart from a solitary woman. Only one man besides C. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...