- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

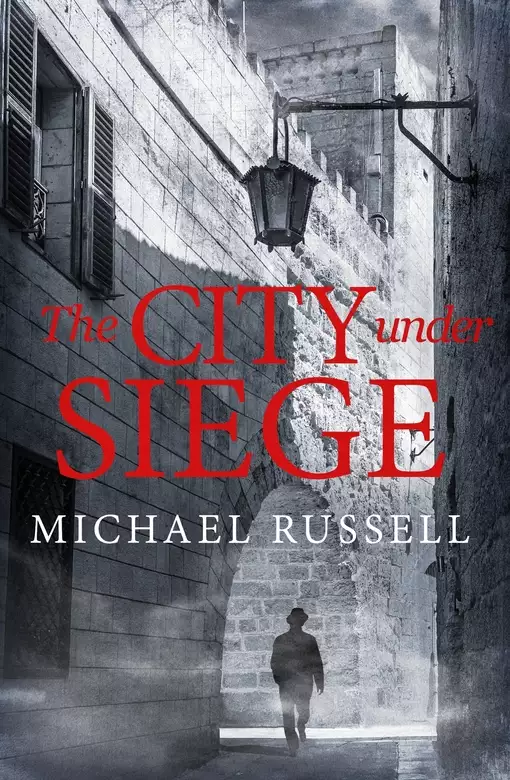

Synopsis

1941, and Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie is ferrying documents between Dublin and war-torn London. When Ireland's greatest actor is arrested in Soho, after the brutal murder of a gay man, Stefan extricates him from an embarrassing situation. But suddenly he is looking at a series of murders, stretching across Britain and Ireland. The deaths were never investigated deeply as they were not considered a priority. And there are reasons to look away now. It's not only that the killer may be a British soldier, Scotland Yard is also hiding the truth about the victim. But an identical murder in Malta makes investigation essential. Malta, at the heart of the Mediterranean war, is under siege by German and Italian bombers. Rumours that a British soldier murdered a Maltese teenager can't go unchallenged without damaging loyalty to Britain. Now Britain will cooperate with Ireland to find the killer and Stefan is sent to Malta. The British believe the killer is an Irishman; that's the result they want. And they'd like Stefan to give it to them. But in the dark streets of Valletta there are threats deadlier than German bombs... Praise for Michael Russell 'Complex but compelling . . . utterly vivid and convincing' Independent on Sunday 'A superb, atmospheric thriller' Irish Independent 'A thriller to keep you guessing and gasping' Daily Mail 'Atmospheric' Sunday Times

Release date: July 2, 2020

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 279

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The City Under Siege

Michael Russell

In the white, tiled room the two porters carried the body from the mortuary drawer and laid it down on the porcelain slab in the middle of the room. Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie turned the pages of a manila file of statements, reports and photographs. The photographs showed the body as it had been when it was discovered, in a grove of trees by a river, surrounded by the debris of a picnic: a tartan blanket, a wicker basket, a piece of cheese, a half-eaten loaf of bread, apples and apple cores, two empty beer bottles, a bloody kitchen knife, a bicycle on its side. Then the body up close, partly clothed; the stomach and the tops of the legs drenched in blood. In black and white, the pictures of the picnic site and the river, in wide shot, looked almost elegant. The sun had been shining. In some photographs its light reflected off the water. The detective looked from the photographs of the body to the body itself.

Beside him Sergeant Dessie MacMahon smoked a cigarette, looking at the young, dead man with disinterested curiosity. He had read the State Pathologist’s report. There would be no more to learn. They were in the mortuary at Naas Hospital for reasons he didn’t much like, checking up on the work of other police officers, looking for mistakes, failings, shoddy work. It was the kind of thing that went with the job he now, suddenly, found himself doing. He didn’t much like that either. It was a job he hadn’t asked for.

Stefan Gillespie continued turning the pages of the file. The only other sound was the slow tick of a bank clock that hung above the mortuary door.

The body of James Corcoran was a fortnight old. Cold storage in the hospital at Naas was cold enough to slow decay, but not to stop it. The smell of rotten flesh had risen up as the porters pulled open the drawer. It wasn’t strong, but as the Sweet Afton Dessie MacMahon was smoking went out, he lit another. Stefan Gillespie closed the file and moved closer to the slab.

It was a boyish face. He looked younger than his twenty-four years. A mop of dark hair covered his forehead, the only part of him that was unchanged by death. The opening that reached from the throat to the chest and stomach, where the flesh had been pulled back for the examination of the internal organs, had been closed up and loosely stitched. As always, with the State Pathologist, it was neat, tidy work. He was a man who gave the dead care and attention; it was something the dead were always owed, whoever they were, whatever reason had brought them to the slab. For Stefan, his work was unmistakable. The body was immaculately clean, washed and tidied, ready for the undertaker when that time came, as it would do soon. The flesh was pale, almost luminous. The colour was deceptive. In reality it spoke not of the cleanliness outside, but of the rot spreading beneath the skin, which would eventually break through and consume it.

There was nothing to surprise Inspector Gillespie, having seen the photographs taken at the scene of death and afterwards, as the body had been stripped and opened up and explored. The wounds around the groin were obvious. They were what made this so striking. There were seven: in the lower stomach, in the thighs, in the penis and the testicles. Now they were only uneven tears in the white flesh, thin, broken lips lined with black, long-dried blood. What was visible did not record how deep the kitchen knife had gone, how hard and how furious the strokes had been. The gushing blood that had covered James Corcoran’s body and his clothes, his trousers and his clean, white shirt, had long been washed and sponged away. The bruising around the throat was still clear, though, grey and yellow, red in places. The fingers that had throttled him had pressed so hard that the hyoid bone had broken. But the savagery of his death had been left behind now. His face was oddly calm.

The doors into the mortuary opened with some force and the tall, bearded figure of the State Pathologist, Edward Wayland-Smith, entered, with the air of impatience that was familiar to Stefan and every other detective.

‘What’s all this to do with you, Sergeant Gillespie?’

‘Your office told me you were here today. A good time to catch you.’

‘That’s not an answer, is it? I’m in the middle of an important meeting. Administration, that’s the thing. Never mind the dead.’ Wayland-Smith grinned. ‘Still, you gave me an excuse to leave the buggers to it. This one’s done, isn’t he?’ Wayland-Smith glanced at the body. ‘Inspector Charles’s, Maynooth?’

‘You might call it an administrative matter, sir. The case seems to have ground to a halt. I’ve been asked to look it over … see if there’s more to do.’

‘To see if Inspector Charles has made a bollocks of it, you mean? It wouldn’t surprise me. I don’t think it’s an investigation that fills anyone with … I don’t know if enthusiasm is the right word, but if it is, there’s probably a considerable lack of it. There’s an element of the proverbial bargepole with which some things are not to be touched, however. I’m sure you know all that.’

‘Do I?’ Stefan smiled.

‘You’ll have read he was training to be a priest.’

Stefan nodded.

Wayland-Smith shrugged, as if that explained everything.

‘But I’d forgotten, they’ve moved you into Special Branch. And it’s Inspector Gillespie now. Good for promotion, but not for making yourself popular.’ He looked at Dessie. ‘He’s dragged you along too, MacMahon.’

‘That would be the word. Dragged. Special Branch wasn’t my choice.’

A look passed between Stefan and Dessie. There was a smile in it, or at least the hint of a smile, but something else from Dessie that wasn’t a smile.

The State Pathologist registered the exchange.

‘You’ve lost weight, MacMahon. That’s no bad thing.’

‘That’ll be something to thank Special Branch for, sir.’

Wayland-Smith laughed.

‘Well, I’m sure we can’t have too many policemen keeping an eye on what we’re all saying, now that there’s a war on that we intend to play no part in. I’m sure Ireland will have a lot to thank you for. I don’t think the state has a great deal to fear from Mr Corcoran, however. You’ve seen him. Is that all?’

Stefan Gillespie said nothing.

All three men were silent, looking down at the body.

‘It was a very vicious attack,’ said Stefan quietly.

‘Very. Unusually so, I’d have to say.’

‘An attack by someone he knew?’

‘I can’t say that, but it seems a reasonable conclusion.’

Stefan opened the file and turned several pages.

‘In the investigation, there seems to be some resistance to talking about the details you’ve given. They beg certain questions that I don’t see asked.’

‘I can imagine that’s so, Inspector. Are you surprised?’

‘Can you tell me what happened – what you think happened?’ Stefan asked.

‘You’ve read my report.’

‘I’m a great believer in the horse’s mouth.’

‘He was strangled. Asphyxiation was the actual cause of death.’ Wayland-Smith moved closer to the slab, looking at the young body with a kind of tenderness, unlike his brusque, impatient manner with the living. He walked around the body slowly as he spoke. ‘The wounds around his groin were inflicted immediately after death. I mean immediately, almost simultaneously. The quantity of blood left that in no doubt. He could barely have been dead.’ He stopped and looked up at Stefan and Dessie. ‘Perhaps he wasn’t, not quite.’

‘He was partially dressed. Did that happen before or after death?’

‘He was as you will have seen him in the photographs, Inspector. His shirt was open, as were his trousers. That’s how he was when he was attacked.’

‘The trousers pulled down.’

‘Some way down.’

‘And he was lying on the ground, before the attack.’

‘Yes. That would be my interpretation.’

‘Was he killed where he was found?’

‘Not for me to say. Given the circumstances I can’t see it could have been otherwise. And I gather that was the conclusion Inspector Charles came to.’

Stefan Gillespie turned over another page in the file.

‘There was semen present.’

‘There was.’

‘Not only from the victim.’

‘No. I would have made that observation, simply on the basis of common sense, from the two areas semen was found on the body, but I was able to establish the two specimens of semen do represent two different blood groups.’

‘We know the killer’s blood group?’

‘In all probability.’

‘So, we assume some sort of sexual act took place, possibly – even probably – consensual, followed immediately by a brutal, murderous attack.’

‘I can only give you simple facts. That’s what it feels like. And you can see, already, why there are a lot of questions no one would be eager to ask.’

‘There’s no evidence there was anyone else involved?’

‘Nothing that I’ve seen. My evidence stops with the body.’

‘There’s nothing that gives us any more information about the other man?’

‘Nothing I could find, Gillespie. I understand there are some fragments of a fingerprint that don’t belong to the dead man. On a beer bottle, I think it is.’

‘Would the killer have had a lot of blood on his clothes?’

‘Some, certainly. Whether it was a lot would depend on how he was positioned when he delivered the blows. There was no resistance, obviously. The wounds were inflicted with … I suppose frenzy was what came to mind when I first saw the body. That still doesn’t mean the murderer was covered in blood. I gather the investigation has produced nothing on who he was, where he came from, where he went. An isolated spot … did anyone see anything at all?’

‘No. There’s barely a thing,’ said Stefan. ‘He’s almost invisible.’

‘Is that so surprising, Inspector?’

‘I’d have hoped for something, sir, more than we have, working out from the scene of the crime. It is isolated, but there’s not even a sighting of two men cycling together. And there’s nothing in terms of the victim’s associations, his friends, things he might have said. He set out on a picnic, after all. This wasn’t something that happened by chance. Time, place … must have been arranged.’

For a moment, again, they looked at the body. It offered no answers.

‘However this encounter came about, Inspector Gillespie, it was, by its nature, secret, utterly secret. Whether the second man was someone James Corcoran had just met or knew well, what they were doing had to be hidden. That’s the point, isn’t it? It’s what we’re fighting. Every effort, presumably on the part of both men, went into trying to make sure they were invisible.’

The black Ford pulled away from Naas Hospital. Dessie MacMahon drove.

‘Maynooth?’ he said in a flat, unengaged tone.

‘Yes. St Patrick’s College.’

‘Not Donadea?’

Stefan Gillespie reopened the file on the death of James Corcoran.

‘I wouldn’t mind, if there’s time. But the scene of the crime can’t mean much after a fortnight. If we were actually investigating this, maybe. We’re here to tick Inspector Charles’s boxes and see if he needs to go back and do it again.’

Stefan didn’t notice the sour look from his sergeant.

‘But I think we should speak to this man Dunne. He seems like the only one in the seminary who was close to Corcoran at all. He wasn’t exactly blessed with friends. Or if he was, Maynooth CID didn’t get very far unearthing them.’

‘There’s a good reason for that,’ said Dessie. ‘They’ll all know enough about what happened, however tight Andy Charles tried to keep it. If any of them are queer they’ll be more worried about that coming out than a dead body, friend or not, and for the rest, they’ll all want to keep well away from it.’

‘We’ll take what we’ve got, Dessie. And I’d like a look at his room. I’m assuming that’s still locked up as part of the investigation. There’s a list of things that were taken to the barracks in Maynooth. Nothing that matters; at least, nothing that produced any evidence. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t miss something.’

‘This is a fucking waste of time, Stevie, you know that?’

‘You could be right.’

‘Andy Charles is a good detective. What are we chasing him for?’

‘We’re not chasing him.’

‘We’re looking for what he’s done wrong, what he missed, what he didn’t do. What else is this for? Does he even know we’re on it? Have they told him?’

‘I’m sure he’ll find out.’ Stefan smiled.

‘Yes, he fucking will, Stevie.’

‘A friend of yours?’

‘If he is, he won’t be for long.’

Stefan took out a cigarette. He lit it, glancing sideways at Dessie.

‘You’re not that pissed off about Inspector Charles, Dessie, or a couple of fellers in Maynooth CID. You’re just pissed off. Well, I am too. I didn’t ask to go into Special Branch. And I didn’t ask for you to be pulled along to work with me either. I don’t want to spy on anyone, let alone other Guards. It’s shite and we both know it. But it’s Superintendent Gregory’s shite. It’s his decision.’

‘His shite is our shite now,’ muttered Sergeant MacMahon.

‘All right, Dessie. I don’t know what the hell it’s about, and I’m no happier than you are being in Dublin Castle with the Commissioner’s collection of old IRA men and narks and all-round arseholes. But if you don’t like it, get used to it, because Terry Gregory will cheerfully tell you it’ll only get worse. I don’t trust any of those gobshites in the Castle, Gregory least of all. And I’m not even welcome there. Anyone they don’t know is an informer … and since they’re all fucking informers themselves, why not? But the last thing you and I need to do is stop trusting each other. We’re here, Dessie. We may get on with it, so.’

Dessie MacMahon did not reply. Eventually he produced a shrug.

Inspector Stefan Gillespie walked across the grass of St Joseph’s Square, the great quadrangle of St Patrick’s College, Maynooth. With him was a young man in the black priestly uniform of a seminarian. The small square of white at his throat was the only break in the black. He wore wire spectacles and a look of seriousness that reflected the conversation he was about to have, as well as his nature. He looked to Stefan unsettlingly like the young man he had seen earlier in the mortuary. He was about the same age. He had the same pale features, even the earnestness that was still, somehow, in James Corcoran’s dead face. There was no real sense that the trainee priest was nervous being asked to talk about his dead friend, but because Stefan could see he was wary, he had said nothing yet. He had asked no questions. He had left Dessie MacMahon to search out a cup of tea and talk to the porter, who had extracted Aidan Dunne from the library. He wanted the conversation to be as informal as he could make it.

St Joseph’s Square was empty save for a few young men hurrying along the straight central drive, late for a lecture. The square was laid out as a garden and Stefan and the young seminarian were walking among trees. The buildings of the college made up the quadrangle, surrounding them on four sides, but the buildings felt a long way off. The space was huge. Long, high, grey walls full of windows, hundreds of them, with the spire of the chapel at one corner. It was a place that had been built to declare its seriousness and its immutability. The rows of windows carried the barest echo of the grace and light of the Georgian terraces being built in Dublin at the same time. In the dark stone and the insistent formality, in the relentless repetition of mullioned windows, there was something fortress-like. The college had been established at the end of the eighteenth century, when the Penal Laws, which tried to make Catholicism invisible in Ireland, were being abandoned. The Penal Laws failed. St Patrick’s was a grand statement of Catholic visibility. This was the biggest seminary in the world. Training priests was one of the few things that Ireland did on a bigger scale than anyone else, anywhere. If there was one place that proclaimed the permanence and the power of Catholic Ireland, it was calmly, peacefully here.

‘I don’t know what I can tell you that I haven’t said already, Inspector.’ Aidan Dunne spoke quietly, breaking the silence Stefan Gillespie had let sit uneasily between them as they walked slowly through the college gardens.

‘You can tell me about your friend being happy.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘That’s what you said, when you were talking to Inspector Charles. He had been happy, noticeably so, in the days … the week before all this happened.’

The young man nodded. He looked slightly puzzled.

‘I don’t know how much you know about what happened … the details.’

‘I only know he was attacked and killed.’

‘Maybe that’s all you want to know,’ said Stefan.

‘Maybe it is. I know it was … it was all very unpleasant.’

‘Unpleasant is certainly one word for it, Mr Dunne.’ The words were spoken quietly, but there was an edge that was almost an accusation. ‘I think you know enough to know … you don’t want to know more. You’re not alone.’

The seminarian looked away; it was true enough.

‘But back to what you told Inspector Charles, Mr Dunne.’

‘If I knew anything, do you think I wouldn’t have said?’

‘You say he was noticeably happy, does that mean he wasn’t usually?’

Aidan Dunne frowned. He wasn’t sure how to answer. Questions he had been asked before were about times, dates, facts, when he last saw his friend.

‘It’s a simple question.’

‘He had his ups and downs; we all do. A vocation isn’t an easy thing. We all face questions, all the time. You can be very sure about your faith and still be unsure whether the priesthood is the right way, if you’re doing the right thing.’

Stefan Gillespie said nothing for some seconds. Then he continued. ‘That’s not what you meant, is it? Is that what you think about when you’re asked about a friend who’s dead, who’s been murdered? His vocation? You were talking about something else you were conscious of. It was in your head. So, there was something unusual about it. It stood out. When I read it, in your statement, it stands out for me. It was … exceptional in some way, is that fair?’

‘Yes, I suppose that’s right, Inspector.’

‘What made him so happy, then?’

Aidan Dunne shook his head and walked on in silence.

‘Let’s look at it from the other end. If being happy was so obvious, his unhappiness was more than the ordinary ups and downs of life at St Patrick’s. If he did have doubts about his vocation, they must have gone deep, is that true?’

‘I don’t know what you want me to tell you, Inspector.’

‘Were those doubts there only because he was homosexual?’

Aidan Dunne stopped, staring at the detective. There was a startled look on his face, but not only shock; there was a sense of fear, as if something that should not be said had been spoken, casually, idly; others might be listening.

‘It’s just the two of us, Mr Dunne,’ said Stefan. ‘I won’t be writing down your answers. I simply want to understand your friend, and to see if there is anything at all, anywhere, that can help us find the man who killed him.’

Aidan Dunne walked on, looking at the ground.

‘You knew he was homosexual?’

The young man nodded.

Stefan took out a packet of cigarettes and offered him one. Dunne took the cigarette. Stefan took one himself and lit both. They walked on again, smoking.

‘You did know?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did he talk to you about it?’

‘Never.’ There was a hint of uncertainty in the word, but only a hint.

‘Until those last few days?’

‘He still didn’t say anything, as such. But I knew. I guess he knew that.’

‘There are other men in the seminary who have the same problem.’

Dunne frowned and said nothing. He looked straight ahead.

‘I’m not asking about you.’

‘I’m not! Jesus! I’m not that way at all.’

‘I’m only interested in your friend. Did he associate with other men, other men here who were that way? I’m sure you have a sense of it. It may be that no one says anything, or looks too hard, but sometimes it’s not so easy to hide, is it? James was your friend. He didn’t say a word about it. You knew anyway.’

‘I can’t talk about this,’ said Dunne.

‘It’s another simple question. I’m assuming he was happy because he’d met someone. Isn’t that what it was? Isn’t that what he said … in some way?’

‘James was very shut in on himself, that’s the only way I can put it. He didn’t make friends easily. I’m not sure he wanted to. I knew because he had the room next door. We got on. I sensed things about him, yes, but I know he had little to do with anyone here. He worked all the time, that’s almost all he did. I think he wanted to work himself into believing he really did have a vocation.’

‘But he didn’t?’

‘I thought … he was using the priesthood to run away from something.’

‘Suddenly he was happy. Someone had made him happy, is that it?’

‘Not someone here. I know that, Inspector.’

‘So, what did he tell you?’

‘He’d been in Dublin for a few days, working at the National Library. He’d met someone. I suppose … he was in love. He didn’t use those words, but it’s what he was saying. And it had made everything clear. He knew what he had to do. He couldn’t stay at St Patrick’s. He knew he didn’t have a vocation.’

‘And that didn’t trouble him?’

‘No, quite the opposite. He said he was going to go home the following week and tell his mother and father. He was going to leave the college. He said he might even leave Ireland. He talked about going to England … I don’t know what that meant, and he didn’t either. Most of what he said didn’t make sense. When I asked what he thought he was going to do … in the middle of a war, he laughed and said it would all be fine, it would all be grand. All he had to do was find a way to live his life the way he wanted. And he believed he could.’

‘And what about the day out, the picnic? You’ve said he talked about it.’

‘He said he was going to meet his friend. That’s all he called him … I think somehow he managed to avoid even the word “he”. It was a day out, they were going to cycle down to the country … there was a place he knew, a place he loved … They were going to make plans about a holiday in England, that’s what he told me. These weren’t long conversations, Mr Gillespie. He was in and out of my room … talking, then going away. He came back to borrow a picnic rug I had … and then he needed a knife for the bread or something … and I had one … that was the last evening he was here. And the next day he was gone …’

‘James told you nothing about how he met this man, where he met him, what the man did? There was no name, no description? There was nothing?’

Aidan Dunne shook his head.

Stefan nodded. He had more than Inspector Charles had got. He had a clearer picture of James Corcoran’s last days, but that’s all. The killer had an existence in his head that he hadn’t had before, but it was only a shadow. Stefan knew Corcoran better, but he knew nothing that helped. He did not tell the dead man’s friend what had happened to the borrowed bread-knife. Stefan looked round to see Dessie MacMahon walking towards him, a mischievous smile on his face.

‘The Dean wants a word with you, Stevie. Canon Mulcahy.’

‘Does he now?’

‘He’s profoundly unimpressed by your lack of courtesy.’

‘Is that what he said?’

‘His exact words: “profoundly unimpressed”.’

‘Thank you, Mr Dunne. And I’m sorry for your loss.’

Stefan Gillespie and Dessie MacMahon walked back towards the college. The young seminarian stayed where he was, as if unaware they had gone. He wasn’t looking at them. He was looking at nothing. He was crying, noiselessly.

Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie stood in the Dean’s study. Behind him stood Sergeant MacMahon, and behind him the college’s head porter. The room was lined with books on every wall, except where the large windows looked out to the drive and the gardens where Stefan had just been walking with Aidan Dunne. Canon Mulcahy sat at his desk, a slight, tight-faced man, wearing a look of almost puzzled benevolence on his face, as if he had been done some small but inexplicable wrong. Stefan imagined he had been standing at the window, not long before, watching the conversation with Dunne, and not liking it. Mulcahy’s face softened into something like a smile. He was comfortable giving instructions.

‘I think your sergeant can wait outside, Inspector.’

‘As you wish, sir,’ replied Stefan. He looked at Dessie MacMahon. The sergeant grinned and walked out of the room. The porter left too, pulling the door shut. Mulcahy did not offer Stefan one of the chairs in front of the desk; instead, he stood up himself and walked round to stand very close to him.

‘I am surprised, Mr Gillespie, that you should come into the college to speak to one of our seminarians without asking to do so, without approaching a senior faculty member. In matters of discipline, I am the first port of call here.’

‘There is no issue of discipline that concerns the college, Canon Mulcahy, just a conversation I needed to have with Mr Dunne that continued conversations he had had with Inspector Charles and detectives from Maynooth.’

Canon Mulcahy drew himself up, regarding Stefan with less benevolence.

‘There is an issue of courtesy, Inspector. It may not be your strong point, but no one walks into this college to question its students without permission.’

‘It’s about the investigation into the death of one of your seminarians.’

‘I’m glad for that information. But you might want to enlighten me about what precisely you have to do with the investigation into that tragedy. I have only just put the telephone down from speaking to Superintendent Mangan at the barracks in Maynooth. His men have been conducting the inquiry ever since poor Corcoran was found, in particular Detective Inspector Charles. Superintendent Mangan has no idea who you are, Inspe. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...