- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Dublin 1940. An IRA attack leaves two guards dead on the streets of Dublin. Two days later, a battle between warring gangs erupts at a race meeting, and on Ireland's east coast the cremated bodies of a wealthy family of five are found in their shuttered, burned-out villa. Dispatched from Special Branch to investigate, Detective Inspector Stefan Gillespie soon finds himself caught in a web of Irish, British and German Intelligence - all playing against each other, all watching each other, and all plagued by rogue operators they can't quite control, as the certainty grows that Hitler is about to invade England. And then, Stephen is sent to Berlin on a sensitive mission. His journey home becomes a dangerous pursuit in which no one can be trusted and the information he carries puts his life on the line.

Release date: May 4, 2017

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

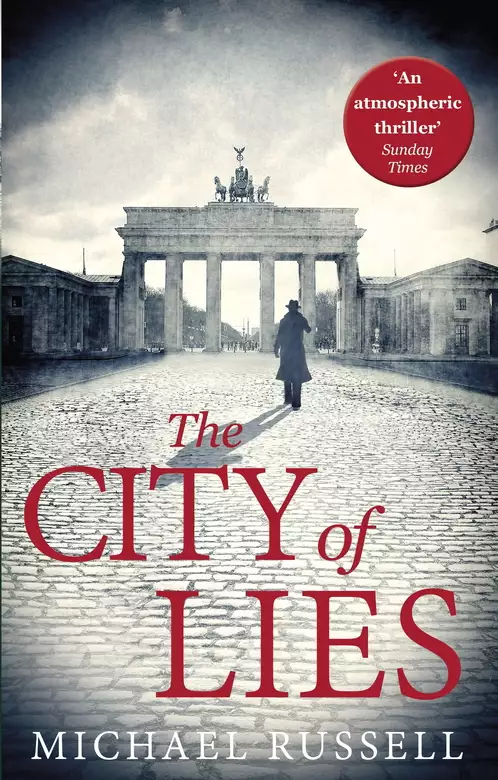

The City of Lies

Michael Russell

At the eastern end of the main street, by the road that eventually leads up into the mountains, is the fair green, where Dunlavin’s livestock markets and fairs were held. It was to that green, as the rebellion of the United Irishmen broke out in 1798, that Captain Morley Saunders rode from Baltinglass to hold a parade of West Wicklow’s yeomanry. In an atmosphere of confusion and panic, he accused some of his men of supporting the rebels, claiming that he already knew who they were. He didn’t, though the political and religious affiliations of the militia men, Catholic and Protestant alike, could hardly have been any secret in such a small community. Whatever information Saunders did have was coloured, inevitably, by petty spite and local bad blood. But when a surprising number of men stepped forward to confess, the sense of panic and confusion only increased. The men were imprisoned overnight in that Doric-columned courthouse, assuming that little more than a flogging awaited them.

The next day Captain Saunders ordered that all the prisoners be executed. Thirty-six men were marched back to Dunlavin Green and shot in batches, by their neighbours, their friends, even by their relations; several more were hanged. Saunders’ motives were partly fear over unfounded rumours of a rebel advance on the town, partly panic over the size of the ‘enemy within’, partly a reckless reprisal for deaths in fighting elsewhere. He may have felt the brutality would close off rebel sympathy. Maybe – probably – he did it because he could.

On a clear September evening in 1940, a short, dark man in his forties, wiry and tanned, wheeling a bicycle, walked along Sparrow Road towards Dunlavin Green, past the Catholic church of St Nicholas of Myra. The sky was clear. There were martins flying overhead, feeding. It was bright and warm still. He could feel the sun on his skin and that troubled him. The bodies had started to stink. The smell had been in his nostrils in the house at Gormanstown that morning. If he had got the smell out of his nose, he had not got it out of his head. And it would be worse now, after another long and hot day. He had to act.

He was shaking slightly, leaning on the bicycle to steady himself. He was sweating, too, but it wasn’t the sun; it wasn’t even the whiskey and the stout at Mattie Farrell’s. He slowed as he passed the church gates. The Angelus bell had started sounding. He halted and crossed himself, mouthing the Hail Mary. He stopped after ‘Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners’; the words ‘now and at the hour of our death’ wouldn’t come. The dead were too much on his mind to let those words out. They were not the long-dead who lay somewhere under his feet, buried in a pit after the massacre of 1798, or even Mattie Farrell’s mother, in a coffin on the kitchen table in the house he had just left. They were the four bodies that had lain for three days in the house that was called La Mancha.

He hadn’t wanted to go to Bridie Farrell’s wake, but he’d had no choice. Not to go would have looked odd. Mattie was a friend. People would have wondered, even his wife and his children would have asked why. He had to behave as if nothing was wrong. That was the only way. It was why he was off now, to check the horses. That was what he did. That’s where he told them he was going. But it was all more time wasted. He had stayed at the wake longer than he meant to, of course. He had drunk more than he meant to, of course. Jesus, no one could blame him for that. Why had he left it so long? Yet that wasn’t the question. Why had he done it? For nothing, for sweet fuck all!

As the man walked on across the green to the wide main street, with its shops and pubs and houses, stretching busily down towards the Church of Ireland church at the far end, he could see people. They were enjoying the evening sun, walking, talking, laughing – all the ordinary things his head had no room for. There were people heading towards him too, friends on their way to Bridie Farrell’s wake. He would have to stop; he would have to speak, all the long length of Stephen Street. They couldn’t know anything; none of them could. But the sense that they would pick up something, would even see inside him, had grown stronger with the whiskey he had drunk. Alcohol had seen him through the wake, but he couldn’t face any more. Unsteady as he was, he climbed on to the bicycle and started to ride. He wouldn’t have to stop; he wouldn’t have to talk. He was picking up speed coming into the town. His head was down. He barely missed Noel Fisher; he didn’t even hear him, roaring, laughing.

‘Did you give Bridie a good send-off, Henry, you drunken bastard!’

Henry Casey cycled on, faster and faster, his eyes fixed ahead, wanting to empty his mind. Only as he turned right to face the domed courthouse and the flat-fronted Garda barracks just beyond it, did he slow down. The proximity of the two buildings was unavoidable, pushing away the chaos in his mind to tell him what he should have done. He should have gone to the Guards straight away. He had known it all along, from the beginning. The feeling that he could undo what had happened swept over him again, so strongly he almost believed it, in the way, as a child, he had woken in the night, for weeks after his mother’s death, still believing that something could undo it all and return her to him.

He turned on to the Kilcullen Road, past the station, out into the high-hedged countryside. He rode slowly. It was a journey he didn’t want to complete. He was sober now, very suddenly. That didn’t make it any easier.

For the rest of the way he saw no one, and within ten minutes he had reached the gates of the avenue that led to La Mancha. He stopped. The long, straight drive, lined with old beeches, framed the white house that lay at the end. There were rooks overhead, flying to the trees to roost. Their cawing was the only sound. He got off the bicycle and walked. It was another delay; a few more minutes to hold on to. To either side of the drive, behind the beeches, neat post-and-rail fencing skirted the track. It was less than a fortnight since he had creosoted those fences. He could smell the tar in the air, still fresh enough for the heat of the sun to draw it from the wood. He looked to his right, hearing the rumble of hooves. Three horses were running across the field. They were old friends. The chestnut gelding, the silver mare, the black filly with the white star on her forehead. They were racehorses. Not much in the way of these things. There were better at any number of stables around the Curragh. But they had hopes for the black filly. It felt like she was something special. She wouldn’t be, of course. They never were at La Mancha. But they were beautiful. He had never stopped thinking that; he thought it even now as they halted, whinnying, then followed him as he continued along the drive. He could see the grass was thin, patched with brown. He should have moved the horses to the new grass by now.

Suddenly there was another sound. A car. He couldn’t see it but it was a car by the house. The engine had just started. Someone was poking around. He stood still. His heart was pounding; his stomach churning. He tasted bile in his throat. He turned and pushed the bicycle between the beeches, flung himself and his bicycle down in a shallow dip. The noise of the engine and the tyres on the stones of the drive grew closer. He flattened himself. The car passed. He didn’t look up until there was no sound. Then, as he inched himself up, he could see the car in the gateway, where the drive met the road. He knew it. The Jaguar Roadster wasn’t an easy car to forget. The white, sleek body, long and low; the black wheel arches. It was the Welshman. Henry Casey couldn’t remember his name. He was not a regular visitor to La Mancha. He had been there only three or four times that Casey knew, on his way to Punchestown or the Curragh for race meetings. But he had been there the previous week. There was no knowing what he had seen now. The doors of the house were locked, the curtains were closed. There was no indication anyone was in. But people would come. Henry Casey had to act. He was out of time. He had been since it started.

He did not go straight to the house. He walked to the back of the bright, white, two-storey building, full of windows, and into the stable yard. There was only one horse in the boxes now. The smell of rotting flesh was strong as he passed a box. La Mancha was an old horse. He had been the last good horse at the stables, but that was a long time ago. He had been out to grass for almost ten years. He was frail; he was coming to the end of his life; but he was still a pampered favourite in the yard. Now he was dead, lying in the straw in his box with part of his head blown away by a 20-bore shotgun. It had taken two shots. Casey could hear a faint, regular hum, even through the heavy doors. Flies.

He opened the door to the barn. The two cans of petrol were just inside, where he had left them. He had been mad not to do it sooner. He picked them up and walked quickly back towards the house. He unlocked the back door and went in, following the dark corridor to the kitchen. The smell was there again, stronger. Not rotten yet, not stinking like the horse, just in the air, still sweet and sickly. There were half a dozen flies crawling over Alice’s face, where the blood was black and dry. They flew up angrily as he approached. He stood, fighting the gagging in his throat. He took the first can and opened it. He poured petrol over her and out on to the rug she lay on. He splashed it over the chairs and the table, and dribbled it across the floor. He breathed in the fumes that drove away the smell of death. He walked out into the back hall, carrying the jerrycans through to the stairs. He trailed the petrol up the stair carpet behind him and soaked the curtains at the half-landing. Then he carried on to the bedrooms.

He went into three bedrooms, one after another. In each there was a dead body. The smell was there, of course, but now all he had in his nose was petrol. Annie lay on her bed in her nightgown. He drained the first can over her and the bedclothes. In the next room the body of Patrick lay under the blankets, his head high on the pillows. He opened the second can and poured out more petrol, splashing it along the floor to the landing. In the third bedroom the body of Simon lay with his face staring up, blank and calm. His eyes were open. It was hard not to look at. He drained the contents of the second can.

He took the empty cans to the top of the stairs, then went back. He took out a box of matches. He struck one a little way from Simon’s bed. He threw it at the body. It went out. He struck another, trembling, and it fell on the floor. He had to move closer. He struck a third match and let it drop. Petrol fumes were in the air now and a sheet of flame shot up. He turned and ran, quickly setting fires in the other two bedrooms. And the fire was taking. As he ran downstairs with the empty cans, the landing carpet was burning. It soon spread to the stairs. When he reached the kitchen he struck a match and dropped it on Alice’s body. Nothing happened. He tried again. Nothing happened. And the matches were gone. He needed more petrol, more matches. It would have to do. He walked back to the hall. The staircase was burning. The fire would soon reach the kitchen. When it did she would burn, as they all would. It would do.

Several minutes later he stood at the front of the house, holding his bicycle. Black smoke was rising from the back, and two of the upstairs windows were full of flame where the curtains had burnt away. There was a crack like a small explosion, as the glass in one of the windows burst, and smoke and flame poured out. He had done all he could. Surely it would be enough. He turned away and rode slowly up the drive, away from La Mancha. He didn’t look back. As he pedalled faster, heading towards the gate, he saw the three horses trotting beside the post-and-rail fence, keeping pace with him; the chestnut gelding, the silver mare, the black filly.

They say an icon is a window, not only a window through which we look into heaven, but a window through which heaven looks at us. Johannes Rilling knelt before the wrought-iron gate that separated the chancel of the Chapel of the Virgin, in the monastery of Jasna Góra, looking at the altar and the dark face of the Black Madonna, Our Lady of Częstochowa. He saw less than he would have liked. The Virgin’s eyes looked at him from the red and black and gold of the jewelled picture, as people said they did, but her gaze didn’t so much penetrate as pass through him. The eyes of the infant Jesus she cradled in her left arm did not meet his; they were turned away, and though the child’s right arm was raised in a blessing, he seemed to look somewhere else, not at Rilling at all.

Hauptmann Rilling had not come in search of benediction. The three days of blitzkrieg that had carried him across Poland with the German Army made that seem presumptuous at best. There might be a time for it when he had finished the job. It was the job he did, a soldier’s job; blood and destruction was its nature. He made no apology for that, even here. If it had to be done, it was better that it was done fast, and it certainly had been; that was the most he could offer. Yet he was still in the Chapel of the Divine Image, on his knees, because he could not pass through the city of Częstochowa and not come. There were other German soldiers in the chapel as he knelt, mostly officers. They stood in line behind him, as he had stood behind others, awkward, slightly shamefaced, silent, not only because it was right to be silent in the presence of the icon, but because they had nothing to say to each other. They knew that what they were doing was very close, for a moment, to opening up the box where they had put away all the things that didn’t necessarily sit comfortably with the Germany they served, or with the very personal oath every soldier had taken to its leader.

The prayer Johannes Rilling was trying to pray didn’t form easily out of the things that filled his mind, even though he felt no need to question himself. But he did realise that he was looking for a place where a prayer of some kind might be heard. The words wouldn’t come. He was conscious of the black of the Virgin’s robe and the red of Christ’s; the colours of war. He heard soldiers shuffling behind him. With his own prayer still unspoken he muttered a curt Hail Mary and crossed himself. There was no window; there was only a mirror.

Walking out of the chapel, he stopped at a table by the door. On it lay a variety of guns: revolvers, pistols, rifles. The Field Police officer by the table nodded as Hauptmann Rilling picked up his pistol and holster. Rilling walked away, looking up at the wall ahead of him, filled with the votive offerings of centuries of pilgrims. Prominent among them were the crutches and staffs and even the ancient, crumbling bandages of those who believed they had left the chapel whole, when they had entered it broken. He had nothing to leave. The organ had started playing. He looked up, listening as he strapped on the holster. It was Bach. He knew he recognised it, but he couldn’t quite place the piece.

‘Lord, from my heart I hold you dear.’

He turned. The speaker was a young SS Untersturmführer.

‘Of course it is,’ said the captain. ‘Thank you.’

‘Bach’s a good choice today. I think they get the message.’

‘I’m sure they do,’ replied Johannes Rilling.

He walked on out of the chapel, into the courtyard. He could still hear the organ. The SS officer knew his music; he probably didn’t know the place that hymn was most often heard was at a funeral. Rilling stopped to light a cigarette.

There were two more SS men outside the chapel. They nodded politely, but they were there to take note of who went in, rank and regiment, at least as far as the officers were concerned. There was nothing to stop a German soldier coming into the monastery – officially, at any rate – either to go to Mass or to look at the portrait of the Black Madonna. The clergy of Jasna Góra pursued their daily course despite what was happening beyond the walls, but the monastery was secured and guarded. For now, the people of Częstochowa were not allowed through the gates. The presence of the Holy Spirit was no threat to anyone, of course, but the spirit of Poland was here, however pale the light; that needed watching. Meanwhile, lists of soldiers who cared to make the pilgrimage to Jasna Góra would find their way to Berlin and the Reich Main Security Office. You had to be very keen on getting on your knees to put your name on those lists, or very bloody-minded. Either way, you were worth watching.

The small town of Żarki lay amongst woods and fields off the road to Kraków, to the south-east of Częstochowa. The town, like Częstochowa itself, had seen little fighting. Within two days of the German invasion the Polish Army of Kraków, like the rest of the Polish forces, was retreating to regroup in the east. A troop of cavalry and an infantry company had passed through the town without stopping. The bodies of some twenty men and a dozen horses lay unburied at the sides of the dirt road where two screeching Stukas had picked them off. Some of the town’s citizens, mostly women and children, had been killed when the Stukas moved on to Żarki itself to make their point more clearly. The area was secure, with no evidence of partisan activity, when Hauptmann Rilling and his infantry company arrived. So it was with some surprise that the captain saw smoke rising from the town as his driver emerged from the woods to the north, to negotiate the potholes and the dead horses. He could hear the crack of rifle and pistol fire, too, sporadic and intermittent.

‘What the fuck’s going on now?’

The driver put his foot down as they moved through the outskirts of the town towards the market square. Rilling took out his pistol. The soldier who sat next to the driver pushed back the bolt on his rifle. There was the sound of gunfire again, and loud voices. It sounded like they were shouting, cheering.

The square was little more than a blunted triangle of beaten earth. The buildings that surrounded it on three sides were mostly single storey, with crumbling plaster and rough thatching. The tower of the church at one end was the only high building. Rilling had already passed Żarki’s other substantial building, the synagogue in Moniuski Street; that was what was on fire. The noise in the square came from Hauptmann Rilling’s soldiers. They stood in a great ring, shouting, laughing, jeering. Inside the circle something like a hundred people were running, round and round, all with their hands clasped behind their heads. As the captain’s car stopped, he knew who they were. Mostly men and boys, with some old men, they were all Jews. Some had beards and sidelocks and wore black, Orthodox clothes; others were indistinguishable from their Catholic neighbours. And their neighbours were there too, standing outside the circle of soldiers, gazing on in silent fear, and crossing themselves.

Rilling’s men were too preoccupied to notice him. As he got out of the car he was conscious, oddly, how young they all were, of their light hair and their bright, rosy faces, cheering and shouting as if they were at a football match. Their faces were contorted with a mixture of hatred and uncontrollable hilarity. They were excited; they were having the time of their lives. He saw his men step forward, as Jews fell behind, beating the offenders with pistols or rifle butts. They kicked the ones who stumbled and fell. They fired into the air, screaming for them all to run faster. The faces of the Jews were filled with pain and terror. Hauptmann Rilling pushed his way through the ring of soldiers. He raised his pistol and fired four times.

‘Stop this! Now!’

His presence silenced the soldiers. The only noise in the market square was the sound of the feet of the Jews, still running, slowing down now. But some did not slow. They kept running as fast as they could, their hands still behind their heads, until one of the old men ran straight into Johannes Rilling and collapsed at his feet. The captain looked down. He put his pistol away.

‘You can stop,’ he said quietly. Then he looked up and shouted. ‘You can stop running! Go back to your homes! Clear the square! Now!’

The Jews in the centre of the ring of soldiers were breathless, fearful, but they started to go, helping each other up, passing nervously through the stationary troops. The Poles who had watched were melting away too. Hauptmann Rilling turned in a slow circle, looking at his men. It was a look of cold anger. But he had seen enough in a few days in Poland; he had seen enough at home. He had no business being surprised. But he had order to keep.

‘Form yourselves into ranks!’

The Hauptfeldwebel, the oldest man in the company, stepped forward and repeated the command.

‘Form into ranks! Form into ranks!’

As if a switch had been pressed, the soldiers moved to the centre of the square and formed lines. The junior officers walked towards Rilling in a group.

‘How the fuck did you let this happen, Company Sergeant Major?’

‘It was not my command, sir.’

‘Then whose was it?’ The captain looked at his officers.

‘Who started this?’ He looked at his Oberleutnant. ‘Weber?’

‘It was just some fun with the Jews, sir.’

‘And burning the fucking town?’

‘It’s only the synagogue,’ said the Oberleutnant.

‘Take the men and put it out, Sergeant, before it takes the town with it.’

The Hauptfeldwebel moved across to the lines of soldiers and was soon on his way to deal with the fire, glad to be out of range of his captain’s anger.

‘I asked you how it started. Who was giving the order?’

‘The SS officer, sir.’

‘Jesus, that’s just what we need,’ said Rilling. ‘We’re moving out tomorrow. The Poles have regrouped across the Vistula. Don’t imagine they haven’t got enough fight left to give you some fun too, gentlemen. Get on with it and get the men in a fit state to fight. You might want to remind them what they are: soldiers. You might want to remind yourselves at the same time.’

Hauptmann Rilling’s officers walked away. Their expressions showed their mixed emotions. They were tight-lipped in the face of a reprimand, but there was resentment, too. Things had got out of control. They knew they should have kept order instead of getting drawn into it. At the same time their captain’s fury was out of proportion. After all, these weren’t people in the ordinary sense of the word, the German sense. The Jews were the scum of the earth and worse; the Poles weren’t far behind. It wasn’t war in the ordinary sense of war. It was about survival. They all knew that. They had been told that what lay ahead in Poland would require no ordinary bravery, but something else, an unflinching bravery of the soul that, when it was all over, would be unspoken, unrecorded, even unremembered. The sentiments were abstract; their job was to make them concrete. It was the way you dealt with disease. No quarter. The men had not heard those words the way the officers had, but they sensed it. Blood spoke to blood; when it did there were no questions. And Rilling’s anger was a question.

Żarki’s Stary Rynek was almost empty. Johannes Rilling stood where he had stood for a long ten minutes now, at the centre of the old square. At one corner a group of old Polish men still talked in whispers. Two of Rilling’s soldiers walked slowly round the square, but they were smoking and laughing. All was calm, though smoke still rose from the synagogue several streets away, and the shouts of the men trying to put out the fire could be heard. Rilling was uneasy. It was a sign of the times. He had seen enough of those signs, everyone had, but it wasn’t his business to interpret them. In so far as he had thought about them it had been to assure himself he could do his job and step round them. But this was only the beginning; he interpreted that much. He knew that in taking back control, in the face of his men running riot, he had taken a step towards losing it.

He looked up at the sound of an engine. He recognised the shape of an open-topped, slope-fronted Kübelwagen jeep, painted in military camouflage. There were four men in it: a driver and a private with a light machine gun in the front, two officers in the back. They all wore army field grey, but he knew they weren’t soldiers. The uniforms bore no regimental markings – in fact, no particular markings at all, except for those of rank – but the caps of the two officers had the death’s head motif of the SS. They were Einsatzgruppen men, answerable not to the military command but ultimately to Heinrich Himmler and the Reich Main Security Office; they might be any combination of SS, Gestapo, civilian police. Rilling waited as the car stopped. The officer who got out, smiling, had a triangular patch on his right arm with the letters SD; he was Sicherheitsdienst, then, SS Intelligence. He was probably the one his officers thought was a Gestapo man. Fine distinctions were unnecessary in those kinds of jobs.

‘Hauptmann Rilling!’

‘I am – and you are?’

‘Obersturmführer Gottstein.’ The man waited a moment, still smiling, as if expecting a response. He shrugged. ‘Liaison officer for Einsatzgruppe II.’

‘I suppose I have you to thank for my men shooting up the town and setting fire to it? It wasn’t exactly what I had in mind when I went to Częstochowa this morning. We move forward again tomorrow. The Polish Army is regrouping in the east. I’d rather they had their minds on that.’

‘It was merely a suggestion, Rilling. When we arrived the Jews were being less than forthcoming about food. It was being requisitioned. Your officers seemed keen to give them a lesson in German manners.’

‘Some manners are probably not ideally suited to the German Army.’

‘You’re as pompous as ever, Rilling!’ Gottstein spun round and grinned at the other officer in the Kübelwagen. ‘I told you he was a pompous ass!’ The SD man turned back to Johannes Rilling. ‘So, you don’t recognise me?’

‘Gottstein,’ said Rilling. ‘I’m sorry, I should have done.’

There was an awkward silence. Gottstein was no longer smiling. There was something between the two men that neither of them was comfortable with.

‘A long time.’ Hauptmann Rilling attempted a smile.

‘Yes, it’s been long enough,’ said the Obersturmführer. ‘I did see your name on the command orders. I wasn’t sure it was you, not until I got here.’

‘Well, it is.’ Rilling shrugged, smiling more successfully.

For another moment they didn’t speak. Then whatever it was that they had both been conscious of in their silence was pushed aside, as if by agreement.

‘I assume you didn’t call to say hello, Obersturmführer.’

‘Prisoners on the Special Prosecution List.’ Gottstein turned back to the Kübelwagen and leant over to pick up a sheaf of papers from the back seat.

‘We’ve detained most of the people on the Żarki list,’ said Rilling. ‘They’re at the school now. Presumably that’s where you’ve just been.’

‘Yes, I’ve checked them. Very thorough. You missed the rabbi.’

‘He’s dead.’

‘He has been replaced.’

‘It’s not my list, Gottstein. It should be a p. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...