- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

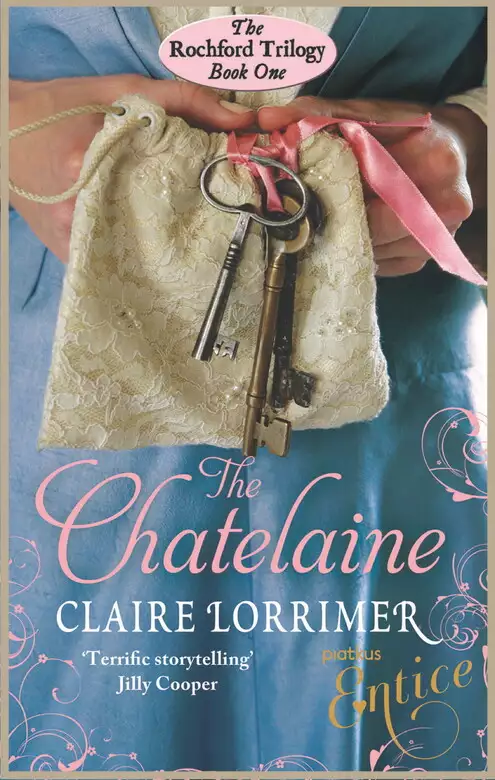

Synopsis

Only Willoughby Tetford, the American self-made millionaire, was shrewd enough to have any misgivings when his beautiful daughter, Willow, married the handsome English aristocrat. Willow herself, seventeen, innocent and deeply in love with her new husband, Rowell Rochford, had complete trust and confidence in the future as she arrived at Rochford Manor in England. And when Rowell's matriarchal French grandmother handed her the keys of the house and told she was the new Chatelaine, Willow believed she held the keys not only to the multitude of rooms of which she was now the mistress but also to love and happiness. On her arrival, she is greeted warmly by her four brothers-in-law: Tony, quiet and studious; Pelham, teasing and flirtatious, the spoilt Francis and the sensitive Rupert. But she has no inkling of the obsession which grips old Lady Rochford because of events in the past to which she, Willow is ignorant. Nor does she realise the terrible repercussions the obsession will have on her own life.

Release date: May 5, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Chatelaine

Claire Lorrimer

GENERAL LORD CEDRIC ROCHFORD Grandmère’s husband

THE HON. MILDRED ROCHFORD

THE HON. GRACE (née ROCHFORD)

Grandmère’s sisters-in-law

LORD OLIVER ROCHFORD Grandmère’s son

LADY ALICE ROCHFORD Grandmère’s daughter-in-law

THE HON. JOSEPHINE ROCHFORD

THE HON. BARBARA ROCHFORD

infants of the above

IRENE BARTON the infants’ nurse

ROWELL, BARON ROCHFORD Grandmère’s eldest grandson

THE HON. TOBY ROCHFORD

THE HON. PELHAM ROCHFORD

THE HON. RUPERT ROCHFORD

THE HON. FRANCIS ROCHFORD

THE HON. DOROTHY ROCHFORD

Grandmère’s other grandchildren

VIOLET GULLY Dodie’s maid

THE HON. SOPHIA ROCHFORD

THE HON. OLIVER ROCHFORD

THE HON. ALICE ROCHFORD

Grandmère’s great-grandchildren

PATIENCE MERRYWEATHER the children’s nurse

WILLOUGHBY TETFORD American millionaire

BEATRICE TETFORD his wife

WILLOW TETFORD their daughter

NELLIE SINCLAIR Willow’s maid

GEORGINA GREY (née FRY) Rowell’s mistress

PHILIP, MARK and JANE GREY Georgina’s children

AUGUSTA FRY Georgina’s aunt

LUCIENNE, COMTESSE LE CHEVALIER Grandmère’s niece

SILVIE, BARONIN VON SENDEN Lucienne’s daughter

BERNARD, BARON VON SENDEN Silvie’s German husband

DR JOHN FORBES the Rochfords’ family doctor

PEGGY FORBES Dr Forbes’ wife

ADRIAN FORBES their son

JAMES McGILL. Havorhurst village schoolmaster

MRS MARY GASSONS his housekeeper

ALEXANDRA McGILL his daughter

THE REVEREND APPLEBY vicar of St Stephen’s Church, Havorhurst

MR BARTHOLOMEW solicitor of the Rochford family

MR FELLOWS bailiff to Lord Rochford

MRS GERTRUDE SPEARS housekeeper

MRS CONNIE JUPP cook

GEORGE DUTTON butler

HAROLD STEVENS footman

JANET UPTON head parlourmaid

PETERS head coachman

JACKSON head groom

BETTY tweeny

LILY maid

servants at Rochford Manor

MADELEINE VILLIER New Zealand girl

MRS MEADOWS her aunt

DÉSIRÉE SOMNERS actress

SIR JOHN BARRATT, BART friend of the Rochford family

ANNABEL BARRATT his eldest daughter

GILLIAN BARRATT another daughter

STELLA MENZIES the Barratts’ governess

LORD THEODORE SYMINGTON

LADY ESMÉ SYMINGTON

friends of Rowell

AGNES MILLER farmer’s wife

MATTHEW MAYBURY Bishop’s Chancellor

MR AND MRS PALEY American businessman and his wife

NATHANIEL CORBETT Willoughby Tetford’s partner

BARRY ADAMS Willoughby Tetford’s junior director

MR GORNWAY brain specialist

DR GOUSSE French doctor

MARIE cook at the Château d’Orbais

FATHER MATTIEU French priest

MOTHER SUPERIOR of the Convent du Coeur Sanglant

PIERRE French artist

MAURICE French artist

MONSIEUR GRIMAUD Parisian modiste

MADAME GRIMAUD his wife

MADAME LULU owner of the brothel Le Ciel Rouge

YVETTE

BABETTE

NICOLE

FIFI

four of her girls

JOSÉ maid in the brothel

ANDRÉ Yvette’s boyfriend

BLANCHE cocotte de luxe

MAXIMILLIAN, GRAF VON KREGE German count

1864

Fourteen times a day the children’s nurse, Irene, stood for ten minutes in the centre of the sickroom waving her rod through

the air. On the end of the rod was a three foot square of flannel cloth moistened in Sir William Burnett’s Disinfecting Fluid

– a patented purifying agent. Doctor Forbes thought very highly of it and had recommended it yesterday as a precaution lest

the two infants were suffering from an infectious disease. But this morning the younger doctor had informed the anxious nurse

and parents that in his opinion, the likelihood was that the baby and the little girl were suffering from brain storms.

It was four o’clock on a dark December evening. An oil lamp, turned low, stood on the table between the baby’s cot and that

of her eighteen month-old sister. There could be little doubt now that the two month-old baby was dying. She was wracked by

convulsive fits, her tiny body contorting grotesquely as she struggled for breath. Beside her, Alice Rochford wept quietly,

powerless to help her offspring. Every now and again she turned in mute appeal to the doctor and begged him to do something

to save her children. But from the young man’s anxious expression and nervous pacing between the two cots, she sensed that he, too, had little hope of their survival.

A huge fire burned in the grate. On a trivet a bronchitis kettle poured steam out into the room. The atmosphere smelt of balsam,

camphor and carbolic despite the fact that both windows were open, the curtains blowing inwards as draughts carried the freezing

night air towards the chimney.

The door opened and the small, plump, erect figure of Lady Clotilde Rochford, the children’s grandmother, came marching into

the sickroom. Her dark, beady eyes swept round to the windows and seeing them open, she ordered the nurse to close them at

once.

The doctor’s feeble protest was drowned by her imperious command that she wanted none of his newfangled ideas in her house;

that he was far too young and inexperienced to argue with her and that the windows were to remain closed. As always when aroused,

Lady Clotilde’s voice betrayed her French origins and her accent became noticeable.

The young man bowed his head submissively. Lady Rochford senior’s reputation was well known to him. He had been warned several

times that she was autocratic, ruled her large household with a rod of iron and totally dominated her son’s wife, Lady Alice

Rochford.

John Forbes decided not to argue with this formidable woman. He was appalled by the misfortune that his very first visit to

Rochford Manor should be for so serious an illness. But at twenty-six years of age, he had only last week come to Havorhurst

to replace the old village doctor who had formerly been in attendance on the Rochford family. The old grandmother was perfectly

correct when she called him, John Forbes, inexperienced, for with a sinking heart he knew that he had still not diagnosed

the infants’ illness.

Alice Rochford’s endless sobbing filled the room. Her mother-inlaw, barely glancing at her, walked over to the cot and looked

down at the baby. Perfectly in control of her emotions, she said sharply:

“I can see the child is dying.” She turned to the nurse. “Irene, tell Burns to send one of the menservants to fetch the parson.

The baby should be baptised at once!”

The child in the adjacent cot now went into a convulsive fit as she, too, struggled desperately for breath. Blood and mucus

dribbled from her mouth. The young doctor wiped it away nervously with a piece of cotton wool. This child, Josephine, had

been ill for nearly two days and despite the nurse’s repeated attempts to feed her, was now suffering from starvation and

dehydration, for she seemed unable to swallow even sips of port wine.

“You’re certain they do not have diphtheria?” asked the grandmother in doubtful tones, her eyes boring into the nervous young

doctor’s face.

“There is no sign of the membrane in the throat,” he reiterated the opinion he had given her that morning. “And neither child

has been in contact with anyone who has the disease.” He turned and stared at the pale, weeping woman by the bed. “Lady Alice

assures me that no-one but herself, the children’s father, you and their nurse have been near the nursery since the new baby

was born. The children cannot have contracted diphtheria without catching it from someone with the disease.”

Lady Rochford nodded. One of her own two sons had died of the complaint during an epidemic in France and she had seen for

herself the cruel white membrane growing over the windpipe until the unhappy child had suffocated. Mercifully her second son,

Oliver, Alice’s husband, had not then been born, for the disease had spread like wildfire through the local community and

her own child’s death was but one of many.

“You must try to resign yourself to God’s will, Alice!” she said in firm tones to her daughter-in-law. “Be thankful that you

are young enough to bear other children.”

There was a knock at the door and as Lord Oliver came into the room, his wife flung herself hysterically into his arms.

“My babies are dying,” she cried.

A soldier by profession, Oliver Rochford was ill at ease in the sickroom; moreover, he did not care for his wife’s uncontrolled

emotionalism although he was a kindly man and sympathised with her distress. Barely recovered from childbirth, she was not

up to this ordeal, he told himself as he patted her head soothingly. He himself was not particularly stricken by the thought

that he was about to lose his two first-born children. Both were girls and he, like his mother, had passionately hoped both

babies would be boys. By the look of things, the new baby had already passed away, he thought as he watched helplessly whilst

the doctor covered the child’s face with the sheet.

Alice Rochford clung to her husband, staring up into his pale blue eyes in despair.

“She has not yet been baptised,” she cried in an anguished voice. “Do you understand, Oliver? She cannot now be buried in

consecrated ground!”

Baron, Lord Oliver Rochford pushed a lock of gingery hair from his forehead and cleared his throat noisily.

“Nonsense, m’dear,” he said firmly. “Parson will bury the infants where I want – where all the Rochfords are buried – in St

Stephen’s graveyard, and that’s all there is to it.”

“But …” Alice began when old Lady Rochford interrupted.

“Oliver is quite right. The Reverend Appleby will not want to lose his living. He will do as Oliver says,” she said pointedly.

She looked at her son – a rotund short sturdy man with ginger side-whiskers and moustache. He had the upright bearing of a

military man and she was immensely proud of him.

“Better take Alice to her room, Oliver,” she suggested. “I’ll stay here until …”

Until the older child dies, thought John Forbes unhappily. Deep down inside, he was a little shocked by this aristocratic

woman’s seeming indifference to death. She was, after all, the infants’ grandmother and as far as he knew, there were no other

children. The return of the nurse, Irene, together with the Reverend Appleby interrupted his thoughts. He stood in the shadows at the back of the room whilst the parson, in his white surplice, prayed for the dying child.

“We beseech Thee to have mercy on this child, Josephine Mildred, and whensoever her soul shall depart it may be without sin

presented unto Thee.”

To the young doctor’s surprise, the parson turned and walked over to the cot where the dead baby lay and in barely audible

tones, began the Baptismal service. Briefly he named her Barbara Alice and committed her soul to God.

Not a little shocked for the second time that night, the doctor realised that Baron Rochford, the children’s father, must

have spoken to the parson regarding the baby’s future burial place.

Old Lady Rochford must have read his thoughts for she now approached him, saying in a low, forceful tone:

“We would not want a family doctor attending our household who was in any respect inclined to tittle-tattle,” she said, her

dark brown eyes boring into his as she spoke. “Naturally, I do not imagine you, Doctor Forbes, would dream of discussing our

affairs with anyone, for I am sure you know what village gossips are – especially regarding those of us who happen to be born

in better circumstances than others. You take my meaning, Doctor?”

He understood her very well indeed and for a moment anger surged through him. What right had this autocratic old woman to

lay down the law – alter the rules to suit her own convenience? Was it money or position that made such people so powerful?

Both, he thought bitterly. There had been many other applicants for the post left vacant by the late Havorhurst doctor and

he, John Forbes, newly qualified, had badly wanted this employment. Lady Rochford could soon turn this country district against

him, he reflected, for the family owned nearly every farm, public house, cottage, mill and smithy for miles around. His patients

were the tenant farmers or employees of the Rochfords and doubtless were well aware of their dependence upon the family –

a fact he was himself now forced to appreciate.

Weakly he nodded, telling himself that the matter of the baby’s baptism was really no concern of his anyway; that he could

count himself lucky that he had not been asked to disobey his Hippocratic Oath, something he would never do. And who could

say but that it might be right not to deny an innocent baby a Christian burial merely because it had died before it had been

named.

But the relief he felt at such self-reassurance was shortlived. Within two hours the little girl, too, was dead, and left

alone in the sickroom with the nurse, he realised he had now to complete two death certificates.

“Cause of death …” What should he write? he asked himself uneasily. The fact was he did not know what had killed them. Could it have been diphtheria after all?

He searched his mind for facts he had learned about the disease and tried to recall the few cases he had seen in hospital.

The various possibilities that had tortured his mind these past two days now crowded in on him again. Tumour on the brain,

epilepsy, croup, hemiplegia … all of these would give rise to convulsions, and could bring about sudden death. But the fact

that both babies had been taken ill at the same time …

Suddenly, with chilling clarity, he recalled a lecture he had attended as a medical student. It had been given by an eminent

German professor and the young doctor could remember little of its subject matter. But what he did now recall was the Professor’s

caution at the end of the lecture.

“Never discard the diagnosis of an illness on the grounds that not all the usual or more obvious symptoms are present. You will come across occasions when even the most predominant symptoms are

absent. The patient may still have the disease you suspect but in that particular individual, the symptoms may be invisible

to the naked eye. The day will come – and I am convinced of it – when we shall discover the means to see inside a body. Then

and then only can we be certain of our diagnosis.”

Shocked, wearied beyond words by the long hours of vigil in the sickroom, the young doctor covered his face with his hands. To admit his doubts now to old Lady Rochford was a terrifying prospect for he had been so adamant in resisting her suggestion that the babies had

diphtheria. Not that he could have saved either child’s life for they would most certainly have died, so swift was the onslaught

of illness. But the woman had seemed content to accept his diagnosis of a brain storm due either to a tumour on the brain

or some other weakness in their constitutions. When he had questioned her about possible hereditary factors, she had told

him quite readily that she was far from happy about her daughter-in-law’s mental condition. Poor Lady Alice had had difficult

pregnancies and births with both children, was frequently ill and cried a great deal, she said. The old family doctor had

had to attend Lady Alice regularly and had stated bluntly that such cases of melancholia during the child-bearing period could

unfortunately be hereditary, though were not always so.

“I am not in the least surprised to hear that she may well have passed on this weakness of the brain to those children,” Lady

Rochford said bluntly. Her voice had softened suddenly. “My poor son! He may never now achieve his dearest wish to have a

healthy son and heir for Rochford.”

John Forbes sighed as he wrote on each certificate the word “Convulsions” as the cause of death. He could foresee that he

might himself be a frequent visitor to the Manor to attend the bereaved mother who no doubt would relapse into yet another

bout of melancholia. But for the meanwhile at least, his work here was done and he could go home.

“See that the room is fumigated very thoroughly with sulphur after the bodies have been removed,” he told the weeping nurse.

He felt a moment’s compassion for the red-eyed girl. She would almost certainly be dismissed from her employment although

she had worked tirelessly and without sleep, caring for the sick children whom she had obviously loved in her simple way.

“Try not to distress yourself too much,” he murmured. “There was nothing you or anyone could do to save them.”

He picked up his black bag and with a last quick glance at the two white-shrouded cots, left the room and made his way downstairs. Everywhere the maids were hurriedly drawing the curtains

in all the rooms. The silence and stillness of death had already penetrated the big house. An elderly butler handed him his

coat and hat and opened the front door for him.

The night sky outside was brilliant with stars, the air sharp with frost which had already laid its white covering over the

lawns and trees. He shivered as he waited for the groom to bring round his gig. There was something oppressive about the big

darkened old manor house which seemed inexplicably to threaten him. Not a single light showed through the curtains windows.

He could hear the sound of wheels crunching on the hard gravel of the drive and the noise from nearby of his horse snorting

with impatience to be off to its own warm stable. The doctor shivered again, his mind tormented by the suspicion that he had

made a terrible mistake.

He shook himself as if to shrug off his misgivings. What did it really matter – except to his own peace of mind? His wrong

diagnosis could harm nobody, least of all the two dead infants. Doubtless before long there would be other children, hopefully

healthy ones, and these two little girls would be forgotten. Diphtheria or convulsions? What did it matter how they had died?

He could not know that it mattered so greatly to the children’s grandmother that never again would she show affection for

her daughter-in-law, nor accord her more than the barest civility; that she was now convinced that poor Alice had brought

into the Rochford family the ugly strain of insanity.

“There must be no more sickly Rochford girls,” she said to her sister-in-law. “We can but hope that next time, Mildred, Alice manages to give poor Oliver a healthy son

and heir.”

It was a year before Rowell, the first of the five healthy, lusty Rochford boys was born, ten years before Francis, the youngest

arrived. By then the untimely deaths of the infants were all but forgotten until, on Francis’ sixth birthday, Alice Rochford

produced her last child.

She died not knowing that it was a girl.

August 1889

Concealed by the curtains drawn across the oriel window in the long gallery, Willow Tetford peered down into the hall below,

her gaze concentrated upon the tall, elegantly-clad figure of the eldest of the Rochford brothers. Rowell was, as usual, encircled

by a bevy of admiring females.

“He is far the most handsome of all the men here tonight,” Willow remarked. “Do you not agree that he looks very beautiful,

Pelham?”

Pelham Rochford turned to the fifteen year-old girl with a mixture of amusement and jealousy.

“You don’t call men ‘beautiful’,” he corrected her not unkindly. He too stared down at his eldest brother but without the

young girl’s adoration. He did not deny Rowell’s good looks which he, being six years younger, often envied. But in Pelham’s

opinion that brooding romantic appearance concealed a nature very far from enviable. Ever since their father had died and

Rowell had inherited the title of Baron and become head of the family, it seemed to Pelham that his eldest brother had grown

far too superior and self-opinionated and to have lost what little sense of humour he had had in his youth. Although still only twenty-four years of age, Rowell had adopted the airs and manners of a far older man and was on occasions objectionably

autocratic with his four younger brothers. Pelham greatly preferred Toby whose twenty-first birthday was being celebrated

this evening with a gala ball at Rochford Manor.

“Who is that red-haired lady Rowell is taking in to dance?” Willow asked urgently beside him. “I don’t think I have ever seen

her before. She is very beautiful, isn’t she?”

Despite the warmth of the summer evening the girl shivered, drawing her night-robe more closely around her slim young body

and pressing nearer to her companion. She was supposed to be safely tucked up in her bed, but her curiosity had got the better

of her and dear, fun-loving Pelham had offered to keep watch whilst she crept from her bedroom to her present place of concealment.

It was nearly midnight and the hall, drawing-room and dining-room thronged with several hundred guests, all attired in their

finest clothes and jewels.

“That is Mrs Georgina Grey,” Pelham answered Willow’s question; and without thinking he added, “Rowell’s mistress!”

Only as he looked down into Willow’s wide uncomprehending gaze did he remember that he was talking to a girl still young enough

to be termed a child. Brought up by a strict Quaker mother, Willow’s innocence was total and he deeply regretted his slip

of the tongue. Now to further his embarrassment, she asked him to explain his meaning.

“I’ll tell you one day – when you are older,” he prevaricated, his voice sharper than he intended in his confusion. “You are

much too young yet to understand about such things,” he added more gently.

Willow’s lips pursed into a pout and she scowled at him as she said sighing:

“That is what Mama always tells me whenever I ask her anything important, especially if it is about love and marriage and

having babies.” She swept the silky curtain of fair hair away from her delicately boned face and sighed again. “Anyway I do know about love. I love you and Toby and Papa and I’m not sure but I think I love Rowell best of all.”

“Then don’t!” Pelham said, this time the sharpness of his tone intentional. “My dear brother Rowell isn’t the least interested

in a child of your age!”

Unperturbed, for she was well aware of her unimportance, Willow merely nodded her agreement. Rowell rarely spoke to her and

it was one of the “Very Special Days” she noted in her diary if he so much as smiled at her once in the course of a week.

“Nobody seems to notice that I am growing up very fast,” Willow remarked, able as always to talk to Pelham on equal terms.

He was exactly as she, an only child, had always imagined a brother might be – teasing, affectionate, sometimes a little patronising

but never more than his three years’ seniority warranted, and never unkind.

Pelham remained silent. He was disturbed by Willow’s innocent remark which was unconsciously provocative. He was only too

well aware of late, that the young American girl had made the transition from child to woman during the summer she had been

at Rochford Manor. She had lost the roundness of childhood and was now tall and slender, and her natural beauty the more remarkable

for her somewhat unusual colouring. From her Scandinavian mother she had inherited her beautiful hair which was almost white

blonde, and her large expressive brown eyes.

Through the thin lawn of her nightgown her small pointed breasts were clearly noticeable and now, when she pouted, he found

himself longing to kiss those pursed red lips and to touch the delicate curved body with his hands. But her immaturity was

a barrier he had not yet felt able to breach. He was both afraid of spoiling that radiant, child-like trust in him and yet

drawn to her as to a magnet. Instead of hiding here with her in the long gallery, he could have been downstairs drinking champagne,

dancing with a dozen or more eager partners, but he preferred to be alone with Willow – a mere child. It was a state of mind

he could not understand.

It was almost with relief that he saw the tall, angular figure of his brother Toby approaching them. Toby was carrying a tray

of food.

“We’re over here, Toby!” Willow called in a low voice as the young man peered short-sightedly over his spectacles down the

long gallery.

“Didn’t realise Pelham was with you!” Toby said in his short, clipped speech – a mannerism caused by acute shyness. “Thought

you might be hungry, Willow. You usually are!”

Willow took the tray from him, her dark brown eyes sparkling.

“You’re dear and kind and thoughtful,” she said as she viewed the delicacies eagerly. Although very occasionally she had been

permitted to eat with the grown-ups, normally she had her meals in the old nursery with the younger Rochford boys, seventeen

year-old Rupert and fifteen year-old Francis, where food was served that Cook considered more wholesome for growing bodies.

Willow did not mind being classified as “nursery” although she always ate with her parents when she was at home. The relegation

was more than offset by the delight of being a guest of the Rochford family for the whole summer whilst her parents were touring

Europe.

They had come from San Francisco to England and rented Langham House for a year. It adjoined the Rochfords’ estate and her

parents, Willoughby and Beatrice Tetford, had warned her that they might not be received by their aristocratic neighbours.

Despite the immense wealth her father had accumulated through his investment in the railroads, Willow was led to understand

that the English upper class was very particular about breeding and she must not be disappointed if they were snubbed. But

this had proved far from the case. Old Lady Rochford, who was the senior member of the family, had made discreet enquiries

and pronounced that the fifteen year-old girl would provide a much needed feminine influence in the lives of her five grandsons.

“Reckon the old lady considers our little Willow too young to be of interest to the boys that way,” Willoughby Tetford had commented shrewdly to his wife. “A good thing we are paying for a real lady governess for the

child. She won’t be at a loss when it comes to manners and deportment.”

The shrewdness that had made him a dollar millionaire was proven once more when old Lady Rochford pronounced herself delighted

by the young girl’s behaviour and disposition, and it was she who proposed that Willow should remain at Rochford Manor whilst

the Tetfords made their European tour.

The arrangement had suited everyone perfectly, not least of all Willow who was delighting in the sudden acquisition of five

“brothers”. Although Rowell, being so much older and the head of the family, had little to say to her, she adored him from

afar and was soon caught in the grips of a mute hero-worship for the elegant, graceful young Baron.

At first she had felt ill at ease in the company of the second brother, Toby. His shyness communicated itself in such a way

that she imagined herself rebuffed, until one day he invited her into the room he called his “laboratory” and haltingly confessed

that he would really have liked to be a doctor. For the first time she saw him smile when innocently she asked why he could

not study the medical sciences if he so wished. Patiently he explained that his grandmother would not permit him to consider

such a middle class profession.

“Gentlemen in England do not have careers,” he told Willow wistfully.

The youngest of the five Rochford boys, Francis, referred to Toby as “The Professor”. Willow had to admit that Toby did often

take on the appearance of an absent-minded scientist when, spectacles slipping to the end of his nose and his mane of dark

chestnut-coloured hair in disarray, he strode through the gardens in a torment of silent thoughts about “his work.” More often

than not he ignored the young girl simply because he did not see her.

Willow had had

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...