- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

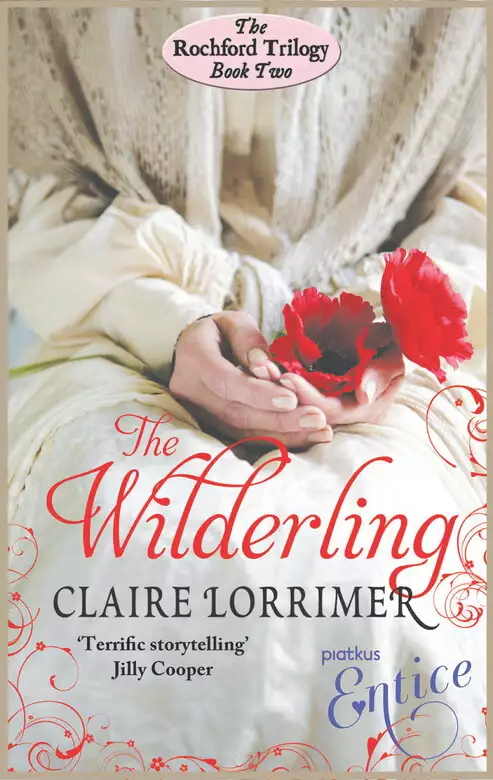

Synopsis

Like a wilderling - a cultivated flower that manages to live in the wild - Lucienne Rochford has survived her terrible early years in France. Although born into the British aristocracy, Lucy was raised in obscurity first in a French convent and then in a Parisian brothel. At sixteen, she is restored to her rightful place as the daughter of the Rochford family, but a devastating betrayal by her father fires her determination to seek wealth and independence at any cost. She learns the ways of society and catches the eye of the handsome and noble Count Alexis Zemski, who swears his love and agrees to marry Lucy even after learning of her past. As World War I shatters Europe, Lucy Rochford begins to learn what life and love are all about...

Release date: June 2, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wilderling

Claire Lorrimer

Richard Bartholomew walked over to the filing cabinet and drew out the largest of the many thick folders it contained. On

its cover was written The Rochford File, in his father’s beautiful copperplate hand.

He took the file over to his desk and sat down, wishing yet again that his father was still alive. Although he himself was

a fully qualified lawyer, at twenty-six Richard did not have the confidence born of experience and the Rochfords were the

firm’s biggest clients. It was not only an honour to be their lawyer but an absolute necessity, for in the small village of

Havorhurst there was little enough legal business to keep the firm financially afloat.

Sighing, he turned the pages until he reached the year 1894. This was the year the late Lord Rochford’s first child was born.

March 14th. Born to Lady Rochford, girl.

March 15th. Baby baptised Sophia Lucienne. Died during the night. Buried St Stephens Church, Havorhurst.

Those terse notes were followed by several pages of entries relating to affairs of the estate. Nothing of importance occurred

until 1899.

February 1st. Son born to Lady Rochford.

February 2nd. Lord Rochford called about his Will.

December 22nd. Child christened Oliver Cedric in St Stephens.

There were no further major events until 1903, when Lady Rochford returned from France where she had given birth to a baby

girl, Alice Silvie, which happy occasion was overshadowed by the disappearance of Rupert Rochford with Dr Forbes’ son, Adrian.

The last record for 1903 was of the death and burial of old Lady Rochford, Lord Rochford’s grandmother.

Richard Bartholomew turned over the page to the following year and now his interest quickened. Here was the second reference

to the child Sophia. Lady Rochford had made a confidential visit to his father expressing her doubts as to the death of the

baby girl.

“No proof to back suspicions,” his father had commented tersely.

“Lady Rochford obviously overwrought. Her doubts raised by unfortunate ramblings of her aunt, Mildred Rochford, presently

suffering effects of a stroke. Explained I could not act on such vague suspicions.”

But early in the following year, 1905, Lord Rochford had instigated an enquiry and Richard’s father had eventually attended

a Consistory Court Hearing in Rochester. The request for an exhumation of the child’s coffin had been granted and on March

14th his father’s entry read:

“Exhumation took place at dawn. No body but a brick in place of corpse. Deeply shocked. Case now in the hands of the police.”

On the next day was a single line announcing the death of Mildred Rochford, the one person his father had hoped might clear

up the mystery.

A month later the youngest brother, Francis, had died as the result of an unfortunate accident at the Manor. Richard Bartholomew

remembered the funeral clearly, although his father had not discussed the details of the accident with him.

Throughout the remainder of the year 1905, the file contained detailed notes of the various police enquiries, their suspicions

endorsed by his father that the family doctor had been involved in the unfortunate disappearance of the Rochford child. Dr Forbes, Lady Rochford and her sister-inlaw, Mildred, were the only

ones present on the night the baby had supposedly died. But by 1906, the law was forced to abandon any hope of finding the

child.

“She has vanished without trace and I doubt the mystery will ever be solved,” his father had written.

Richard reflected sadly that the old man had died without knowing that Sophia Lucienne Rochford had arrived home on 7th May,

1910. Was it only nine months ago, he asked himself, that he had been urgently summoned to Rochford Manor to be told the astonishing

news?

Richard closed the file, relying now on his memory of that meeting to clarify his thoughts. His first impression that afternoon

was that Lord Rochford was clearly very drunk. His client stood in the library, back to the fire, red-faced and only partly

coherent as he rambled on for some time about his wife’s infidelity and her desertion of him. Richard had heard before his

jealous assertions of Lady Rochford’s affair with his eldest brother, Tobias, who had followed her to America. Lord Rochford

had wanted Richard to begin divorce proceedings against his wife but the lawyer had been forced to point out that there was

not one shred of evidence of adultery. Nor, as Lord Rochford kept insisting, that either his son, Oliver, or his youngest

daughter, Alice, were illegitimate.

It had been close on half an hour before his client had suddenly come out with the problem he wanted Richard to deal with

– the amazing appearance of his missing daughter, Sophia.

The girl had not been present. For reasons Richard was later to understand, she had remained at home only two days before

her father had found a boarding establishment to which she had been hastily despatched. Bit by bit, he had managed to elicit

the facts from his inebriated client. Apparently the child had grown up in a convent orphanage in France. How she got there

remained a mystery. At the age of ten she had been put into domestic service with a hat-maker in Paris.

The thought of a Rochford performing the menial tasks of a maid was shocking enough, Richard had thought, but it was several

minutes before he could bring himself to believe the end of Lord Rochford’s garbled story. Sophia – Sophie as she was then

called – had been persuaded to change her employment and went to work as a waitress in a brothel called Le Ciel Rouge. Inevitably she progressed (or should the word have been regressed, he wondered) into the oldest profession in the world,

and had subsequently been earning her keep in this house of ill-repute.

Lord Rochford did not appear to be half as shocked as was Richard himself. He swept aside Richard’s doubts, swearing that

the girl had seemed shameless and told him quite openly what she had been about.

“She might well have spent the rest of her young life there but for that idiot Dr Forbes. Took it into his head four years

ago to go and find her, y’know,” Lord Rochford informed him, helping himself to yet another whisky.

So his father’s suspicions had been well-founded, Richard thought now. Then, he had felt only concern lest the police might

become re-involved if Forbes proved to have been the child’s abductor and his illustrious client were caught up in a most

unsavoury scandal.

But, as Lord Rochford pointed out with remarkable shrewdness for a man who had certainly consumed half a bottle of whisky

if not a great deal more, Forbes was dead and could not be questioned as to how he had known where to find Sophia Rochford.

“We shall have to try to solve the riddle ourselves – discreetly!” Lord Rochford had reiterated several times. His daughter

had told him that three years ago Forbes had offered to buy her out of her terrible employment and according to Sophia, he

had gone back to England to raise the money her employer was demanding. But he never returned.

Richard re-opened the file and turned back to the entries made in that year. He felt a moment of triumph when he found a brief

comment by his father stating that the old doctor had died in the same month as Sophia claimed to have seen him. Small wonder

he had not returned for her, then! Forbes had given the girl no clue as to her real identity but had presented her with a

gold locket. By a stroke of Fate, the locket had been broken and on the back of the photograph it contained, were the names

Cedric and Alice Rochford and the date of their wedding at Havorhurst. With commendable courage, the sixteen-year-old girl

had saved sufficient money and set out for England to see if she could trace her forbears.

“She arrived in Havorhurst three days ago,” Lord Rochford had ended his story. “The vicar looked up the register and next

day, she was on my doorstep – the very day her mother departed for America.”

“You have proof the girl is your daughter?” Richard had asked anxiously.

But Lord Rochford was in no doubt – and for one main reason. It seemed Sophia was a walking image of her mother – the only

difference being in the colour of her eyes.

“And those could as well be my sister Dorothy’s – or Rupert’s,” Lord Rochford stated. “I’m convinced she’s my daughter, Bartholomew,

and now I want you to prove it. There’s one other clue that might help you – that Convent she went to was not very far from

the country house in Epernay owned by my late aunt, Lucienne le Chevalier. My grandmother was French, you may remember, and

Aunt Lucienne was her niece. I suspect my grandmother had a hand in all this and I mean to find out what really happened.”

Richard had not understood at first why Lord Rochford had sent his daughter away so hurriedly. But then he was given a graphic

description of the girl and understood his precipitateness.

“Not only was she dressed like a street-walker but she talked like one!” Lord Rochford had grunted. “Couldn’t let the servants

start gossiping; it would be all round the village in no time. I’m told this boarding establishment is renowned for its success

in training girls to speak and behave like young ladies. They take a great many children of the nouveaux riches who are hoping

to raise their social standing by marrying their girls off to gentlemen. My daughter can stay there until they’ve re-educated

her. After all, she has the right breeding and I’ll say this much, apart from her clothes and the paint on her face, she looks

well-bred. Dainly little thing! Pretty, too. Once the school has finished with her she can run Rochford now m’wife’s left

me.”

It had been Richard’s opinion that Lord Rochford should have notified his wife at once of the reappearance of the child. But

his client would not listen to the suggestions. Bitter and unforgiving, he was determined to keep Lady Rochford in ignorance

and Richard had no legal justification for insisting otherwise.

The following day, Richard had been called to the house again and instructed to set about finding the missing pieces of the

puzzle. He left at once for France, armed with a faded sepia photograph of the late Mildred Rochford and a miniature of Willow,

Lady Rochford, as a young girl.

“Spittin’ image of Sophia,” Lord Rochford told him. “Like enough to get the girl identified.”

It had not taken long to verify the girl’s story. The Mother Superior of the Convent identified Aunt Mildred as the woman

who had brought the child to her, although she referred to her as Miss Beresford – obviously a pseudonym.

But there the clues to the past ended and Richard had to return to his client without solving the riddle as to how or why

the baby had been spirited away from her mother and sent to France.

It was a lucky afterthought that had prompted Richard Bartholomew to ask Lord Rochford to look once more through his grandmother’s

effects to ascertain that there were no further clues. Amongst the letters the old lady had kept from her soldier husband, they had found one from a French priest, called

Father Mattieu, which at long last provided the vital missing piece of the puzzle.

Dated October 1896, it read:

“Your most generous contributions both to my Church and to our orphanage arrived safely together with your letter. I am sure

I do not need to tell you, dear Lady Rochford, how anxious I am to assist you in this delicate matter. I can assure you a

place will be found for the child in the Convent orphanage where she will be carefully looked after in total anonymity. I

understand perfectly your desire to protect your illustrious family name from any possible rumour concerning the child’s abnormality

and your secret shall remain with me as if you had spoken in the Confessional. Not even the Mother Superior will be advised

as to the child’s true identity …”

There were further flowery phrases and expressions of gratitude and a receipt for a banker’s draft of five hundred pounds

sterling – a large enough sum to draw a whistle of surprise from Lord Rochford.

“Hell of a lot to pay out for hush money,” he had said bluntly.

“But why, Sir?” Richard Bartholomew asked. “Why did your grandmother go to such trouble to hide the baby?”

Lord Rochford shrugged his shoulders.

“Had this bee in her bonnet about insanity,” he explained. “My mother died of melancholia and before that, there had been

two girls who died in infancy from what was then diagnosed as ‘brain storms’. Her last child, my sister Dorothy, was malformed.

Grandmère believed there was a hereditary strain running through the distaff side of the Rochfords. Doubtless she feared the

next generation of girls would be abnormal in some way too. I seem to recall that the baby was premature and a bit unsightly.”

He frowned thoughtfully.

“Forbes must have helped Grandmère – but then he was always a weakling and did what my grandmother told him. In any event,

my wife and I were told that the baby had died. Since those days, of course, my brother Toby has disproved the insanity fears, established that Dorothy had had poliomyelitis and

that the infants had died of diphtheria. By the look of it, there’s nothing wrong with this girl, either. Pretty little thing!”

Richard put the Rochford file back in the drawer thoughtfully. By “nothing wrong with the girl”, Lord Rochford must have meant

she had no physical deformities. But her way of life was surely a terrible and irreversible handicap! He could not understand

how Lord Rochford could pay so little regard to it. Yet he had seemed concerned only with avoiding any scandal.

“Can’t have the Rochford good name put at risk!” he kept reiterating. “That’s why I decided to call the girl by her second

name – Lucienne. Less chance of anyone ever connecting her in the future with Sophie Miller, as she was known in France. As

for my grandmother – there’s no point blackening her name by letting the truth be known.”

He had concocted a wild story about the baby being abducted by the wet-nurse and how when she died, she had confessed the

truth and Lucienne’s whereabouts at last became known.

Much as Richard wished to please his most important client, he refused to have any part in this explanation Lord Rochford

intended to give to his friends and neighbours. It was tantamount to being criminal slander, he had pointed out – putting

the blame, which should be laid at his grandmother’s door – onto the shoulders of an innocent woman who was not alive to defend

herself.

But his protests were swept aside and he had been firmly instructed to mind his own business.

Not for the first time, Richard wished his father were still alive to advise him. He himself saw no way in which he could

do more than warn Lord Rochford of his legal position. He could not forbid him to repeat such a palpable lie.

Now the man was dead and he, Richard, had taken it upon himself this morning to advise Lady Rochford of her child’s existence,

contrary to his client’s orders. When she arrived in England, he would be obliged to tell her also of her daughter’s past – a task he dreaded.

It occurred to him now, that he might be able to pass on this unsavoury duty to Mrs Silvie Rochford, Lady Rochford’s sister-in-law.

She would not be so affected as the girl’s mother by such shocking revelations.

Richard glanced at his watch. It was almost four o’clock. Soon Lucienne Rochford would be arriving back from her boarding

establishment and he must go up to Rochford Manor to meet her. Curiosity and anxiety gripped him alternately. He was uncertain,

too, of her feelings towards the dead man laid out on his bed awaiting burial. He hoped the girl would not be too distressed

at the sudden death of her father. Fortunately, he would not be obliged to tell her that the man had been hopelessly drunk

when he had fallen from his horse. The family doctor, Peter Rose, had not deemed it necessary to put as cause of death anything

more than the bare fact that Lord Rochford had broken his neck. Privately he had told Richard that his liver was so damaged

by alcohol that the severe fall might have ruptured it and finished him off. The truth was, neither he, Rose, nor anyone else

had ever liked Lord Rochford, and when his wife left him taking the two children with her to America, no-one had blamed her;

nor blamed the eldest of the brothers for going with her. Tobias Rochford was as well liked as his brother had been unpopular.

Richard reached for his black frock-coat and hat from the mahogany clothes-stand and picked up his kid gloves and malacca

cane. Unless the Rochford chauffeur had lost his way, he should be back with his passenger at any moment, he thought. It would

not do for Richard to arrive at the Manor late.

But he was in plenty of time. The parlour-maid conducted him to the library and left him with copies of The Illustrated London News and Punch. Within five minutes, she returned bearing a large silver tray. Miss Rochford had arrived, she told him, and would join him

in the library for tea.

Although Lord Rochford had told Richard how like the daughter was to her mother, he was totally unprepared for the sight of

the girl who now came into the room. Her bone structure was delicately aristocratic, her movements fluid and graceful. Dainty,

perfectly proportioned, she looked every inch what he knew she was not – an innocent, fresh, sixteen-year-old child on the

brink of womanhood. Her voice, when she spoke, was melodious with a slight French accent. Her opening remark was even more

of a surprise to him.

“You are Mr Bartholomew, the lawyer, are you not? Tell me, please, is it true that the Will is not read until after the funeral?”

Richard managed with practised control to hide the brief sense of shock her words engendered. After all, he told himself,

less than nine months ago Lucienne Rochford had not even known of her father’s existence. Only convention required her to

show some grief at his death.

Avoiding a direct reply to the girl’s question, he said:

“I have taken the liberty of making tentative arrangements for your father’s funeral for the day after tomorrow, Miss Rochford.

Your uncle and aunt in Paris have telegraphed to say they will be here tomorrow. Your Uncle Tobias will be accompanying your

mother from America.”

The girl’s large, violet-blue eyes, which had been wide with curiosity, now flashed brilliantly as she leant forward in her

chair, frowning.

“What has my mother to do with this? You may not be aware, Mr Bartholomew, that my father made it quite clear to me that her

name was not to be mentioned in this house. I do not want her here.”

Richard coughed uneasily.

“Forgive me for interrupting you, Miss Rochford, but I must comply with the law, even if it should contravene your father’s

… er … his private feelings. Your parents were not divorced. Lady Rochford retains her legal status as his wife and is now

your legal guardian.”

Lucienne Rochford’s eyes narrowed as she digested this information. The man sitting opposite her felt a moment of astonishment

at the look of calculation openly apparent on the girl’s delicate young face. He had momentarily forgotten the past events

of her life and had been entirely captivated by the youthful innocence of her outward appearance. In her prim, high-necked,

blue serge school dress, she looked even younger than her sixteen years.

“Your mother is a charming and gracious lady,” he added quietly. “I am sure you will very quickly come to admire and love

her.”

Lucienne’s small mouth pursed into a sulky pout. She tossed her head slightly, loosening a coil of ash-blonde hair.

“I do not want to meet this woman who deserted my father,” she said coldly. “Moreover, I can never feel affection for her

– nor, it would seem, does she have any affection for me. Since my return home, she has made no effort to come to England

to see me.”

Despite himself, Richard smiled.

“Lady Rochford can hardly be blamed for that omission,” he said gently, “since she was unaware until yesterday of your existence.

Your father forbade me to advise her of your unexpected return to the family fold. In fact, no-one was to be made aware of

your presence until you had completed your year in Norbury.”

Lucienne gave a quick, Gallic shrug of her shoulders.

“It makes no difference,” she said, her tongue rolling on the “r” in a manner which betrayed her French upbringing. “But it

is a waste of her time to come to England now. I shall obey my father’s wishes and she shall not be allowed in my house.”

This time, the young lawyer could not withhold the anxious gasp which escaped his lips.

“Miss Rochford, I am afraid you are under a considerable misapprehension if you believe that this will be … er, your house. Your young brother, Oliver, is of course the new Lord Rochford.”

The look in the girl’s eyes was one of total disbelief. She gave a light, pretty laugh of genuine amusement.

“It is you who are mistaken, Mr Bartholomew. My father promised me that I would be his heir; that if I learned to behave like

a real lady, he would give Rochford Manor to me to run as I pleased – the servants – everything. He promised me.”

Richard looked away from her searching gaze, his cheeks colouring slightly with embarrassment.

“I am very sorry to have to disappoint you, Miss Rochford, but there has obviously been some misunderstanding. It was certainly

your father’s wish that when you had completed your schooling, you would return here to take control of the house and act

as his hostess. In the absence of Lady Rochford, it was a natural and sensible plan. But the estate – it is not within Lord

Rochford’s control. It is entailed, you see – that is to say, it passes automatically to the eldest male heir. In this instance,

that is Oliver. Were there no male offspring, the title and estate would pass to your father’s eldest brother. Do you understand?”

The girl jumped to her feet, two red spots of anger burning in her pale cheeks, her eyes flashing and her veneer of demureness

gone.

“Since you are a man of the law, Mr Bartholomew, of necessity I must believe you. But it is intolerable, intolérable,” she repeated in French. “My father tricked me … cheated me. He is like all men – not to be trusted. And to think that I,

who should have known better, allowed myself to believe him …”

Suddenly she burst into tears. Richard sprang to his feet and the next moment the girl threw herself into his arms and was

sobbing against his shoulder.

“Please, please try to calm yourself,” he said awkwardly, the more so as her proximity had begun to affect his emotions in

ways that were very far from professional. Her perfume was clouding his senses and he was painfully aware of the gentle heaving

of her breasts against his chest, and the sweet, silky softness of her hair against his chin. Gently he eased her back into her chair and with a sigh of relief, seated himself at a safe distance opposite her.

Lucienne Rochford blew her nose delicately into a tiny lace handkerchief and ventured a glance at her companion from beneath

dark, damp lashes.

“You will help me, will you not?” she asked appealingly. “If what you tell me is true, I have nothing – nothing in the world

that is mine. Not even my name …” she added with a hint of genuine bitterness.

“Of that at least, I can reassure you,” the young man said eagerly. “You were baptised Sophia Lucienne Rochford and your name

is in the church register. I have seen it myself. I think your father’s decision that you should be called Lucienne was, in

the circumstances, a wise one made entirely in your interest. It is far less likely that on some future occasion you would

be associated with … with …”

He broke off floundering, and Lucienne’s tears gave way to a mischievous smile he found totally enchanting.

“You do not have to pretend with me,” she said with engaging honesty. “You know, Mr Bartholomew, there have been times this

past nine months when I have become quite ennuyeé … how do you say, bored … with pretence. I have longed to say to Miss Talbot and to the pupils, that my real name is Sophie

and that I worked for four years in a brothel in Paris called Le Ciel Rouge, where I was known as Perle.”

The young man coughed, wishing he could talk to her as a friend rather than as a lawyer. But his duty must, he was aware,

come first. He leant forward earnestly and said:

“You must never, ever talk of such things, Miss Rochford. I am sure your father explained that the most important asset a

girl of good family can have is her good name, her reputation. Whatever has happened in the past – for which you can in no

way be blamed – you are a Rochford. It was your father’s wish to launch you in Society as his daughter and ultimately to find you a worthy husband.”

Lucienne shrugged, her finely curved brows drawn into a slight scowl.

“I do not know if I wish to be ‘launched in Society’. Certainly I have no wish to be married. I will not be any man’s slave.

I agreed to my father’s wishes for one reason only – because he promised to give me this big house and the servants and as

many horses and carriages as I wanted. Even a motor car of my own. For this I have endured that dreadful Establishment for

the training of young ladies. Now you are telling me none of these things will be mine.”

“I would be failing in my duty if I told you otherwise,” Richard Bartholomew said gently.

“And this Oliver who will be the new Lord – the owner. Is he not just a boy – a child?”

“He is twelve years old, Miss Rochford. Your sister Alice is younger.”

Lucienne shrugged indifferently.

“My father said they were bastards.”

The lawyer swallowed nervously.

“I must warn you that that statement is slanderous,” he said. “You must never say such a thing again, Miss Rochford. Despite

what your father may have told you, there is no proof that either child was born out of wedlock – in fact, to the contrary.

Were you to say such a thing publicly, you could be sued in court for many thousands of pounds damages.”

Lucienne shrugged once again.

“So! It makes little difference to me. What I wish to know, Mr Bartholomew, is if my father has left me any money in his Will.”

Her bluntness unnerved Richard still further. He said awkwardly:

“I fear I would be acting unprofessionally were I to advise you of the contents of your father’s Will before it is read after

the funeral.”

Lucienne’s head tilted to one side and she looked with soft appeal into the anxious grey eyes of the young lawyer, assessing

his vulnerability. He was by no means immune to her – that she had sensed immediately when he had greeted her. She judged

him to be in his mid-twenties, very correct and conventional in his manner and attire – and quite possibly still a virgin.

She held out both hands towards him and, instinctively, he grasped them in his own as she said:

“We can be friends, can we not, Mr Bartholomew? It is my hope that we shall be so. I am very much alone. I need a good friend

whom I can trust – to whom I can talk with honesty. You must see how badly I need your help in a time like this. I do not

even have a father now to whom I can turn for advice.”

“But of course, of course, Miss Rochford, I am honoured to be your friend. I … I understand your disappointment and indeed, Lord Rochford should not

have allowed you to believe that you could be his heir. I don’t think I would be violating professional etiquette were I to

tell you that it was his intention to change his Will – he told me so – but I fear he never inst

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...