Chapter One

Innisfree

The wind at Innisfree talks. Late at night, just outside the rear windows of the house, the voices rise up from the beach below the sea wall, slither through the grass and whisper around the eaves. Sometimes it is the low murmur of lovers under the filmy curtain of the Milky Way. But often, it is the conspiratorial rumble of those whose only purpose on the shore in the middle of the night is secretive, furtive. The words are indecipherable, but the voices rise and fall with inflection. The wind converses—with the house, with the sea, with itself.

The first time I heard the voices, I froze in my bed, silent and still, straining to understand what they were saying, convinced they were men arguing about breaking into the house. I am a woman alone with a cash business. Everyone knows that. Easy prey.

I keep a gun in a wooden box under the bed. No one knows that, except perhaps old man Lyons who runs the Edgartown Hardware where I purchase my ammunition along with my nails and buckets and garden tools.

I mentally prepared myself to unlock the box and load the pistol, when I realized the voices were continuing in an endless, monotonous loop accompanied by the shushing and high-pitched whistle that I recognized as the voice of nature, not of men. I let down my guard and lowered the window by my bed. Enough of that disturbance. And then I slept.

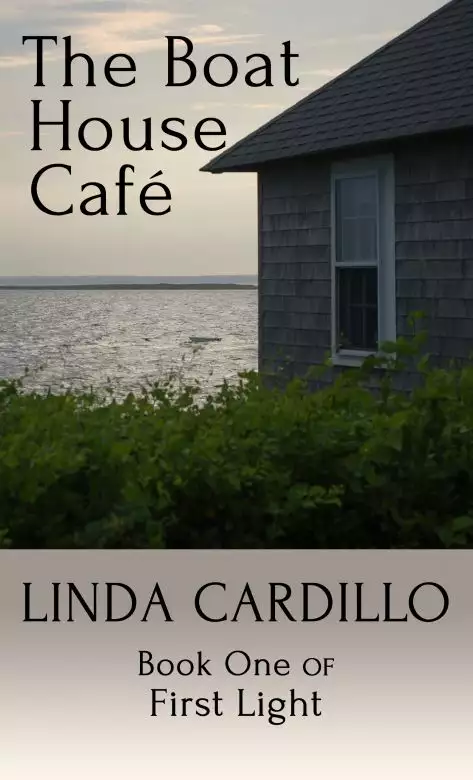

After that night, the murmuring of the wind no longer disturbed my dreams, and became one more confirmation of the wisdom of leaving New York to set up housekeeping at Innisfree. Another is the afternoon lull between lunch and supper customers, when I sit with my cup of tea on the porch of the Boat House Café, overlooking Poge Bay.

A tangle of wildflowers—daisies, beach roses and thistle—climbs up the bank and quivers in the wind, beckoning the finches and the monarch butterflies. Beyond the flowers and the birds, the water dances and the sun spreads a covering of silver lace upon the bay, not unlike the tablecloth my granny tatted for my mother before she and Da left County Kerry for Martha’s Vineyard. Sunday after Mass in Edgartown, my mother spread that cloth on our dining table and my sister Kathleen and I set out the dishes.

Ma left a cold lunch at the Knolls for the Bradleys, who always went to dinner at Rose Jeffers’ place on Sunday evenings, leaving her free to cook us dinner. She taught me to cook, Ma did. Roast chicken, beef stew, colcannon, pound cake, pies. Were she here now to see the Boat House and how it has flourished, she would recognize her recipes and her careful kitchen management. I know to the penny what it costs me to serve a meal at the Boat House. I don’t skimp on the quality of the food I put on the table, nor do I let the Connors Market Store on Main Street, where I get my provisions, overcharge me. But I also am not timid in setting a fair price for what I offer, and my customers come back for more.

If it was Ma who gave me the skills to cook for a living, it was the Jordan Marsh bakery in Boston that taught me how to serve a customer with respect and grace. When I took my waitressing job in New York, many of the girls didn’t understand that at all. If they got orders mixed up or had trouble in the kitchen that caused delays, they never apologized to their customers or soothed the displeasure with another cup of coffee or an extra cookie on the dessert plate. I knew there were rewards to treating people well–financial rewards in my pocket, introductions when the time came for me to make my move and buy this place.

If anyone were to ask me why I came here (although no one does), I would tell them, “This island was my childhood home and the source of the only happy time in my life.”

My brothers and sisters and I were free to roam the beaches and woodlands and moors of Chappy because our parents were caretakers of the Bradley mansion on North Neck that everyone referred to as the Knolls. As little ones we saw no distinction between us and Ned Bradley–we all played together by day and then everyone in the neighborhood went home for supper–we to the caretaker’s cottage, Felicia and Ellen Bellamy to their house down the road and Ned up the hill to the Knolls. The food was plentiful, the pace of life unhurried and the cares of the adult world blissfully unknown to us.

That I had to leave that idyllic existence was not my choice. Bad times hit the Bradleys when the market crashed in ’29. They lost the Knolls and everything else. Without the Knolls, they had no need for a caretaker and cook, and Ma and Da picked up and moved us to Boston soon after it became clear they’d not find any other work on the island. I was seventeen at the time. Old enough to understand our misfortune–and our dependence on people like the Bradleys. When the full force of the change in our lives hit me, it was like the wallop of a monster wave at Katama that emerges out of nowhere and catapults you onto the hard, wet sand.

We lived in a tenement, with the only light a dim gray sliver that seeped in through dirty windows facing a shaft. The odors of rancid cooking oil and unwashed bodies permeated the stairwells. We were assailed by wailing babies and the voices of angry men who couldn’t find work and desperate women struggling to put food in their children’s bellies.

That place robbed my Ma of her soul and her voice. On Chappy, she’d sung, especially in the evenings when the moon rose over East Beach and her work at the Knolls was done. Kathleen played the piano and the little ones—Daniel and Patrick and Maureen—gathered at Ma’s feet, exhausted from a day in the open air. She sang all the tunes she had learned in the old country, holding on to that piece of her life as best she could.

We had no piano in Boston, but Ma knew the songs well enough to sing without Kathleen’s accompaniment. But after a few months she was too tired one night to sing, and the little ones, no longer free to run in meadows and climb apple trees, were too agitated to sit still and listen.

I think Ma’s silence was the hardest part for me. Her voice could have drowned out the suffering that shouted at us, not only from the dank hovel that had become our home but from every corner of the city. Without her voice, we slipped farther and farther from everything we had known and loved on Chappy.

When we left Chappy I took a bag of stones with me. I had collected them over the years, wandering along the beach. They were all perfectly smooth and rounded, their rough edges worn away by the sea. At night in bed I emptied the sack and held them like talismans in my hand. Rubbing the stones as if they were Aladdin’s lamp, I made a vow to myself that I would escape the sadness that engulfed us and return to Chappy. I didn’t know how long it would take me, or what I’d have to survive, before I got back.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved