Chapter One

Having Seen Your Face

Michelangelo

1534

Florence

“Florence does not love you, Michelangelo, but Rome will.”

Night visitors. Subdued voices. Despite the low murmurs, it is impossible to ignore the urgency, the warning in their message.

“His Holiness, Pope Clement, summons you. Not merely for his own pleasure, but for your safety. You have too many enemies in Florence. The Duke Alessandro de’ Medici you know. His rancor toward you has only been held in check by his fear of his uncle on the papal throne. But there are others, hidden behind false smiles. The pope says, ‘enough of hiding in the closets of your friends.’ He can better protect you in Rome. You must leave now,” they insist.

Michelangelo observes the faces of these papal messengers in the candlelight. They had not awakened him. When they made their stealthy entrance, he was bent over his worktable, sketching the staircase for the Medici library. Marble dust spills from his hair where it had settled earlier in the day, when he’d been at work on another project, an unfinished sculpture of Apollo.

He is almost sixty. Tired of being pursued to fulfill the demands of others. Weary of the complaints of his ungrateful relatives, currently asleep below. Bereft at the loss of his beloved younger brother. The words spoken by these midnight visitors strike a nerve.

Florence does not love you.

“Urbino!” He shouts for his assistant.

The young man rouses himself and enters the studio, his eyes widening at the presence of strangers.

“Prepare the horses and saddlebags for a journey. We leave tonight.”

“Where are we going? What shall I bring? Shall I inform anyone of our departure?”

Michelangelo answers the last question first. “Leave no word at all. Pack only the drawings I have been working on for the pope's altar wall and enough money to get us to Rome. These gentlemen will accompany us.”

He sees the visitors exchange glances. They must have been expecting a more difficult task in persuading him. When Julius was pope, his messengers had been chased back to Rome empty-handed by a much younger Michelangelo. Not tonight.

Urbino moves silently around the room, gathering the drawings Michelangelo requested and rolling them into a leather pouch. He finds Michelangelo's warmest cloak thrown in a heap by the door and presses it into his master's hands, along with fur-lined gloves and the battered felt hat he refuses to replace. Michelangelo takes the warm clothing as Urbino descends to the horses.

“Do not wake the rest of the household,” he cautions.

The young man turns his head and nods.

The pope's men are pacing, casting anxious glances at the eastern sky for the first signs of dawn. Michelangelo observes them as he pulls on his boots. He has done this before, escaped one city or another ahead of enemies; fled through secret passageways; eluded those who would break down doors or pursue him over mountain passes. He vows to himself that this will be the last time.

He forces himself up from the bench as he hears Urbino's whistle. The horses are saddled. He grabs the satchel with the drawings, wraps the cloak around his shoulders and heads down the stairs.

Urbino waits in the courtyard with a lantern, stamping his feet in the cold. He hands Michelangelo a sack, weighty with coin.

“I had to climb over three snoring men to get to the strongbox, but I woke no one,” he assures Michelangelo.

“Well done. Now to the road, before the whole city, let alone the household, realizes we're gone.”

The artist, Urbino and their papal escort ride hard in the bitter cold and push beyond the boundaries of Florentine jurisdiction before they stop. Michelangelo never turns to look back.

When they finally arrive in Rome, the pope's men insist on bringing him to Pope Clement at once.

“Are you afraid I’ll slip away from the pope as I have from his nephew?” But he goes with them. Clement is not the first pope he has served. He has learned to pick his battles, and this is not one of them.

As their small party charges through the Vatican corridors, he catches the shock of recognition on the faces of various men in the papal court. At least one, a bishop, moves quickly away.

“That one will have a messenger galloping to Alessandro de’ Medici within the hour,” he murmurs to his travelling companions.

“Did we not warn you truthfully?”

“I came, didn't I?”

They are halted outside the pope's audience chamber by two of the Swiss Guards installed by Pope Julius decades before.

“His Holiness is in conversation with two noblewomen from the south. We have been ordered to deny entry until they depart.”

“Maestro, perhaps I should go on and open up the house and find us some dinner?”

Michelangelo sees the wisdom in Urbino's suggestion. There is no need for his young assistant to wait for Clement. It is not Urbino the pope has summoned. Some of the weariness brought on by the journey is relieved by Urbino's mention of the house in the Macello dei Corvi. Michelangelo had purchased it with money secured when he’d renegotiated his contract with Pope Julius's heirs for the tomb that has burdened him for far too long. Clement had stepped in, found him a lawyer and made known his own interest in having Michelangelo freed from the overwhelming demands of Julius's original grand plans.

“I have waited long enough to have you for myself and my plans,” the pope had shouted when he first took office.

The statues for the much-reduced tomb stand in the garden of Michelangelo’s house. They are a reminder of the still-uncompleted work, but the house itself is a well-ordered refuge, not a hovel of a workshop and makeshift living space as he’d had when he was a younger man.

“Buy us some fish for tonight. And get the fires going. My body will need warmth before I can begin whatever it is Clement has as his heart's desire.”

Michelangelo seeks out a bench and leans against the wall, the weariness that had been kept at bay by the urgency of their departure now creeping through his old man's bones. He closes his eyes but is granted only a brief respite as the door to the pope's chamber is thrust open.

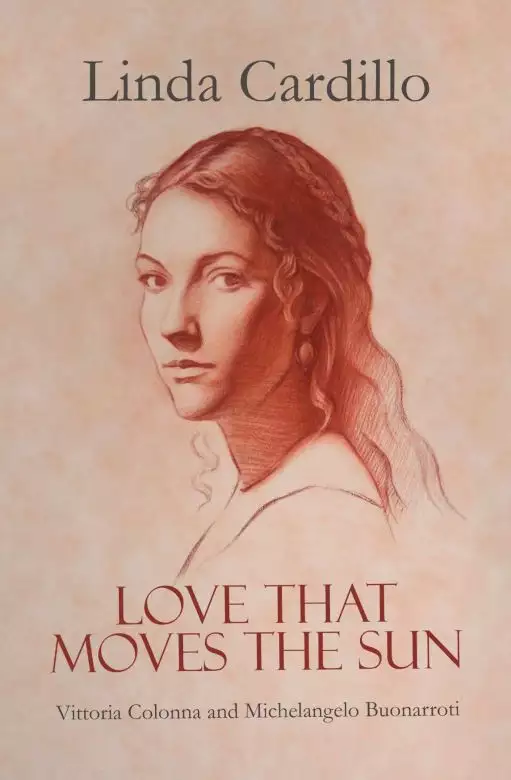

He rises to his feet as two women emerge. One is dark-haired, severely dressed, agitated. The other, attired in a Spanish gown, moves serenely. But the haunted quality of her face suggests an intimacy with anguish. From beneath her veil, a wisp of gold curl is visible. She moves past without noticing him, her head bent as she listens to the high-pitched chatter of her companion.

“Who is that woman?” he asks the guards.

“The poet Vittoria Colonna, the Marchesa di Pescara. The widow of the hero of Pavia.”

He knows the name. He knows the poems. Of course, he reflects. This is how he would have imagined her face, her presence. This is how he would have painted her.

He watches her move away, still attentive to the other woman, and is glad he has come to Rome.

Michelangelo has slept only fitfully since his arrival in Rome two days before. Despite his investment in a good bed, he has tossed uncomfortably, trying to find a position that eases his aging muscles, sore from the strenuous pace of the journey. If he were honest with himself, however, he would acknowledge that his lack of sleep has more of a mental than a physical cause.

Once again, he is at the mercy of yet another demanding pope. Giulio de’ Medici, Pope Clement VII, is dying and wants a legacy. A fresco of Christ's Second Coming.

How many times must I tell them, he reflects, that I am a sculptor, not a painter?

He drags himself from the rumpled site of his nightly struggle, shrugs off the breakfast Urbino offers him and trudges in the direction of the Vatican, unable to avoid any longer the blank wall that awaits him in the Sistine Chapel.

When he arrives he is relieved to see that the altar end of the chapel is empty. He has successfully avoided the morning Mass, and most of the attendees have dispersed. He dislikes the drone of voices that reverberate off the walls and the ceiling. When the room is full, he can hear the din from several corridors away. Today, however, all is blessedly quiet.

He has brought neither measuring tools nor the preliminary sketches Urbino carefully packed when they made their escape from Florence. He wants no encumbrances on this first encounter with the wall. He needs to observe the expanse, to touch it, to grasp its dimensions so he can begin in his mind to fill it. Before he paints, he always imagines.

He paces, mainly to stretch his tightened muscles, still coiled from gripping the flanks of his horse. The pacing helps him concentrate, blocking out any distractions as people enter and leave the chapel. He has also noticed that it dissuades people from approaching him with intrusions.

His concentration is broken by a sudden squall of movement—the heavy footsteps of guards followed by a gust of white. Pope Clement's unmistakable voice calls out from the midst of this cloud of motion.

When they were boys in Lorenzo de’ Medici's house—Michelangelo as a student in Lorenzo's art school and Giulio, the orphaned, bastard son of Lorenzo's brother Giuliano—Giulio had been the noisy, demanding one. As the youngest, Giulio had to work hard to be heard. When he flies into the chapel now, Michelangelo stops his pacing and faces him with folded arms, waiting for his explosive tirade to end.

“They told me I would find you here. I was about to march over to your house myself and drag you out of your bed or your workroom—wherever you have hidden yourself for the last two days. I told you. I do not have much time left, Michelangelo. God has already whispered twice in my ear that He was calling me home, and both times I answered Him that I still had more to do. This wall is what remains of my legacy. I will see you paint it before I die.”

“Am I not here? Did I not promise you?” The artist continues to stand. He does not kneel to kiss the pope's ring.

“You are here. But where are the drawings, the scaffolding, the pigments? Have I not advanced you sufficient funds to undertake this endeavor?”

I cannot work if I am to be continually interrupted on his whim, Michelangelo broods. Better to speak of my need for solitude now before he gets in the habit of stopping by for a visit every day. He is not afraid to express himself frankly with the pope. He and Giulio understand each other.

“I have everything I need, Holy Father, except the solitude to implement what resides up here.” Michelangelo taps his brain with a stained finger.

“Just see that those ideas start migrating to the wall. Soon.”

With a flourish, the pope turns away from Michelangelo and leaves the chapel.

When the pope makes his departure as abruptly as he has burst in, Michelangelo resumes his solitary contemplation. But out of the corner of his eye he senses hurried movement, hears the rustle of silk sweeping across the marble floor and a woman's voice murmuring urgently, “Come, Vittoria.”

The poet. Was she here again? Michelangelo follows the voice to see the serene woman from two days before trailing her companion. The other woman appears to be in a great hurry to pursue the pontiff, but Michelangelo detects in the poet almost a reluctance to leave the chapel.

When she reaches the doorway she stops and faces him. At first he assumes she’s paused for a final glance at the ceiling. It is what people often do, although he himself never wishes to contemplate the fresco again after the years he spent painting it.

But the poet does not look up.

She regards him, with intention. Not accidently, as if her gaze is focused on something else and he happens to fall into her line of sight. No, she has deliberately altered her path to see him.

He studies her as purposefully and knowingly as she considers him. She intrigues him. Her poems have made their way to Florence and have certainly been a topic of discussion in his circle. But she is an enigma, despite the grief and deeply felt emotion revealed in her words. Her beauty, tinged with ineffable sadness, is remote, detached. That he sees all this, in the flash of time since she moved past him and then turned to face him, astonishes him.

With her glance alone she appears to be offering this insight into her. She is pursuing something, of that he is sure. And she seems to be seeking it in him.

He cannot avert his eyes. He has never before encountered a woman with such a direct and compelling gaze. She conveys a power and authority that both unnerves him and makes him hungry to be engulfed.

And then her spell is broken. The voice of the other woman beckons her. But before she leaves, the poet nods to him, acknowledging their wordless exchange.

As she departs, he notes the stiffness and formality of her Spanish gown in sharp contrast to the vulnerable beauty of her pale face. One of the ribbons on her sleeve has become undone, a sliver of black silk that ripples behind her when she turns away from him.

He casts a final, fleeting look at the wall and realizes he has no more room in his thoughts to consider the pope's commission this morning, even though the angel of death is hovering in Clement's shadow.

He leaves the Vatican and wanders slowly back to his house, aware of his yearning and his loneliness.

The next day he is in his garden, surrounded by the half-finished statues that remain to be completed for Pope Julius's tomb. But he ignores their hulking presence and sits sketching in the sunlight, taking advantage of the unseasonably warm fall day. Urbino insists on wrapping a cloak around his shoulders and brings him a heated cup of wine. The young man is good to him. Sensible, caring. Not a burden as some of the others have been, foisted upon him by misguided family members.

He dozes for a few minutes, warmed by the sun and the wine, when a commotion at the gate rouses him.

Urbino comes running back.

“Maestro, it's Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici with a beautiful woman.”

Michelangelo groans. Now Giulio is sending his nephew to urge him along. Despite the very real dangers to Michelangelo in Florence, perhaps he should have stayed, rather than submit to being constantly watched and prodded. He rises to greet the cardinal and his companion. He wonders which of Ippolito's mistresses is with him. The cardinal's red cassock and broad hat obscure the woman as they approach. And then he sees the dress, unmistakable in its cut and fabric. The dress worn by the poet the day before.

He runs his hand over his hair and beard, smooths his jerkin and throws off the woolen cloak.

“Urbino, bring more wine and cups. And see if we have any cakes. If not, run to the baker.”

The young man looks at him in astonishment, frozen.

“Go!” Michelangelo orders and Urbino scampers off.

“Maestro, good afternoon! I hope we are not disturbing your work or my uncle will not forgive me. May I present the Most Honorable Marchesa di Pescara, Vittoria Colonna? Lady Vittoria has expressed an interest in your current work and His Holiness asked me to arrange a meeting.”

Like your uncle, you believe you can come unannounced whenever you please, Michelangelo reflects. I am your servant, subject to your whims. But the words he speaks out loud are quite different. He takes her hand and bends over it with a kiss. Her touch is delicate yet confident. He notes that despite exuding the fragrance of lavender in which they were probably bathed, her fingers still retain the tell-tale ink stains of a dedicated writer.

“My lady, you honor me with your visit.”

“And you honor me by so graciously accepting our intrusion. Please forgive us for coming unannounced, but the cardinal assures me that you do not stand on ceremony.”

“My house is always open to Rome, my lady. Especially to a Roman such as you.”

Neither one of them mentions the striking encounter they had the day before, but the memory of it lingers in the look that passes between them.

“Come, come sit with me! Unless the air is too cool and you wish to go inside?”

“On the contrary, Maestro, I relish the outdoors and have missed the opportunity to be in the open air since my arrival in Rome.”

“If I may ask, what brings you to Rome?”

“The same thing, I imagine, that calls you here. The pope.” Her eyes twinkle as she speaks. She glances at the nephew, but he seems to be in agreement. All three of them obey Clement.

She launches into her own question. “I am eager to hear of your plans for the altar wall. I know that it’s to depict the Last Judgment, a topic that transfixes me with its message. I can think of no subject more fitting for our times. Would you not agree?”

“We live in a world very different from the one that inspired my earlier work. And I am a different man. To be honest with you, my lady, I have only begun to envision how I might portray Christ's Second Coming.”

He sees that Ippolito is already inattentive. Word is, the young cardinal is more interested in parties and plays than the theology of his uncle's wall.

“Shall we wander around the grounds to see the statues, Eminence?” he asks Ippolito. “My servant will be bringing refreshments shortly and we can sit then.”

He hopes if they meander through the garden, Ippolito can more easily drift away from their conversation, relieving him of the pretense of courtesy and allowing Michelangelo to pursue his exchange with the poet. She rises enthusiastically in response to his suggestion.

“I have always enjoyed walking as I discuss the great questions that challenge my thoughts.”

As Michelangelo anticipated, Ippolito soon finds another path and leaves them to their conversation. But even without him nearby and listening, Michelangelo refrains from bringing up the previous day. The poet avoids the topic, as well, keeping their dialogue focused on art.

“I am fascinated by the role art can play in devotion. Do you consider the uses to which your work will be put when you first set out to create it?”

“I am always mindful of my patron's intentions when a work is commissioned, but as it grows beneath my hands, it often takes on a life of its own. And how others respond after I complete it, well, I cannot control that. As much as I would prefer to....”

“It must be a great responsibility, knowing that all eyes will converge on your work and take meaning from it.”

“But surely you’ve experienced the same terror when someone reads your poetry.”

She stops and looks at him with the penetrating gaze that had stirred him in the Sistine Chapel.

“It is terrifying! In the beginning, I didn't write my poems for others' eyes and ears. They were my private grief. But now that moment is past. The words do not belong solely to me anymore.”

“Is that why you’ve stayed away from society?”

He senses her closing down her openness. He has never been adept at courtly conversation. He prefers to delve beneath the surface of things or not at all. Clearly he has ventured too far in this first conversation, assuming a level of affinity between them because of their unspoken communication the day before. He is an old fool. Better to engage in these philosophical discussions with his intimate circle of friends, with whom he can bare his soul. No matter how intensely she has seen into him, no matter how eager she seems to be in her search for answers, she is still a noblewoman and a pious widow. The barriers between them are as impenetrable as the fortifications he once designed but never saw completed for Florence. He hopes he has not frightened her off.

At this moment Urbino arrives, breathless, with a carefully wrapped packet of cakes. Michelangelo and his guests return to the rough-hewn table where they began their visit.

His sketches are still lying about and he begins to roll them up. She stops him, placing her slender hand on one that he has not yet retrieved.

“Is this a preliminary sketch for the wall? May I?”

He nods.

She holds it out in front of her, examining the figures scattered haphazardly across the page. Her eyes flare with that same intensity she directed toward him in the chapel. She traces one of the figures with her finger, pausing on the countenance of a woman filled with undefined longing. He has drawn it from memory, his hand working swiftly to capture what he saw there.

She puts the sheet down and covers her face, stifling a barely audible sob that he senses only he has heard. The cardinal is too busy selecting a cake. But Urbino, observant young man that he is, grasps that something has happened.

“My lady, you have caught a fleck of dust in your eye. Please allow me to offer you this handkerchief and a glass of wine.” Urbino leaps to her side, each hand offering a remedy.

She smiles at him, wipes her eyes and takes the wine. “To the artist,” she proclaims, lifting her goblet in Michelangelo's direction, “who sees humanity's secrets and brings them to life on the page.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved