- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

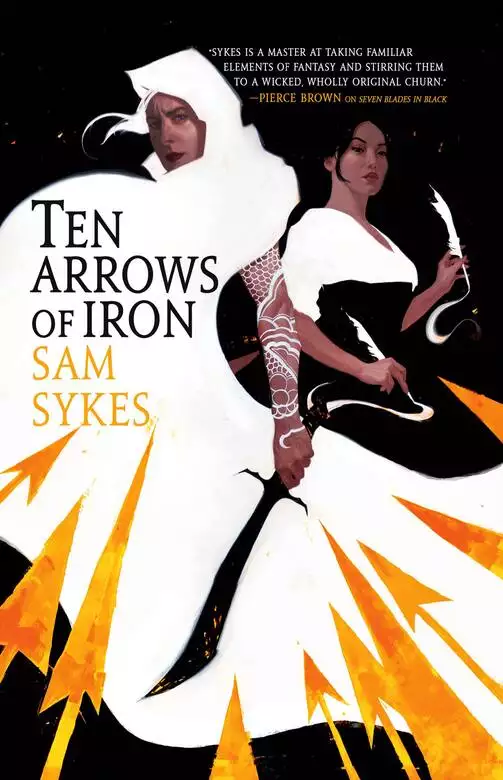

Synopsis

An outcast mage caught between two warring empires must either save the world or destroy everything she loves in the second novel of "an unforgettable epic fantasy" trilogy (Publishers Weekly).

Sal the Cacophony -- outlaw, outcast, outnumbered -- destroys all that she loves. Her lover lost and cities burned in her wake, all she has left is her magical gun and her all-consuming quest for revenge against those who stole her power and took the sky from her.

When the roguish agent of a mysterious patron offers her the chance to participate in a heist to steal an incredible power from the famed airship fleet, the Ten Arrows, she finds a new purpose. But a plot to save the world by bringing down empires swiftly escalates into a conspiracy of magic and vengeance that threatens to burn everything to ash, including herself.

For more from Sam Sykes, check out:

The Grave of Empires:

Seven Blades in Black

Ten Arrows of Iron

Bring Down Heaven:

The City Stained Red

The Mortal Tally

God's Last Breath

The Affinity for Steel Trilogy:

Tome of the Undergates

Black Halo

The Skybound Sea

Release date: August 4, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 720

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Ten Arrows of Iron

Sam Sykes

The day the sky rained fire began like any other.

Meret awoke before the dawn, as he always did, to grind the herbs he had dried last week into tinctures and salves that would cure by next week. He gathered the medicines he needed to, as he always did—balm for Rodic’s burn that he had gotten at the smithy, salve for old man Erton’s bad knee, and as always, a bottle of Avonin whiskey for whatever might arise in the day—put them into his bag, and set out. He made his rounds, as he always did, and visited the same patients he always had since he had arrived in Littlebarrow three months ago.

The name was a little unfair, he thought. After all, it was a long time ago that a woman had built a shack to live in beside the cairn she had constructed for her only child. Since then, enough people had found it a good place to stop on sojourns into the Valley that it had grown to a township worthier of a name that matched its thriving circumstances. But as it wasn’t his township, he thought it not his place to protest the name, no matter how much he had grown attached to the place.

While it was nowhere near as big as Terassus or even the larger towns in the Valley, and it still had its share of problems, Littlebarrow was one of the better places his training had taken him. The people were nice, the winter was relatively gentle, and the surrounding forest was thick enough for game but not so much that larger beasts would come sniffing around.

Littlebarrow was a fine place. And Meret liked to think he had helped.

“Fuck me, boy, you missed your true calling as a torturer.”

Not everyone agreed.

He glanced up from Sindra’s knee, now wrapped in fresh antiseptic-soaked bandages, to Sindra’s face, contorted in pain, with keen distaste that he hoped his glasses magnified enough to demonstrate how tired he was of that joke.

“And you apparently misheard yours,” he said to his newest patient. “I would have thought a soldier would be made of sterner stuff.”

“If my name were Sindra Stern, I’d agree,” the woman growled. “As the Great General saw fit to call me Sindra Honest, I’ll do you the courtesy of pointing out that this shit”—she gestured to the bandages—“fucking hurts.”

“It hurts much less than the infection the salve keeps out, I assure you,” Meret replied, cinching the bandage tight. He dared to flash a wry grin at the woman. “And you were warned about the importance of keeping the joint clean, so in the interests of honesty, I believe I could say I told you so?”

Sindra’s glare loitered on him for an uncomfortable second before she lowered her gaze to her knee. And as her eyes followed the length of her leg, her glare turned to a frown.

The bandages marked the end of her flesh and the beginning of the metal-and-wood prosthetic that had been attached months ago. She rolled its ankle, as if still unconvinced that it was real, and a small series of sigils let off a faint glow in response.

“Fucking magic,” she said with a sneer. “Still not sure that I wouldn’t be better off with just one leg.”

“I’m sure you wouldn’t be able to help as many people without it,” Meret added. “And the spellwrighting that made it possible isn’t technically magic.”

“I was a Revolutionary, boy,” Sindra said with a sneer as she pulled her trouser leg over the prosthesis. “I know fucking magic when I fucking see it.”

“I thought that the soldiers of the Grand Revolution of the Fist and Flame were so pure of ideal that vulgar language never crossed their lips.”

Sindra’s face, dark-skinned and bearing the stress wrinkles of a woman much older than she actually was, was marred by a sour frown. It matched the rest of her body at least. Broad shoulders and thick arms that her old military shirt had long given up trying to hide were corded with the thick muscle that comes from hard labor, hard battles, and harder foes. Her hair was prematurely gray, her boot was prematurely thin, and her heart was prematurely disillusioned. The only part of her that wasn’t falling apart was the sword hanging from her hip.

That, she kept as sharp as her tongue.

“It’s the Glorious Revolution, you little shit,” she muttered, “and it’s a good thing I’m not in it anymore, isn’t it?”

“True,” Meret hummed. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to treat you.”

“Yeah, lucky fucking me,” Sindra grumbled. “I wouldn’t mind a couple of alchemics our cadre medics used to have, though. A hit of those and I could fight all night.”

“I am but a humble apothecary, madam,” he replied. “And while herbs and bandages take longer, they heal just as good.”

Sindra sighed as she winced and hauled herself to her feet, her prosthesis creaking as she did. “You’re just lucky that it’s a choice between keeping you around and keeping soldiers around. If it were a choice between a smart-mouthed apothecary who couldn’t heal for shit and, say, a Hornbrow who hadn’t eaten in days, I’d slather myself in sauce and pry its jaws open myself.”

He agreed, but kept it to himself.

Littlebarrow had been fortunate enough to escape most of the battles between the Revolution and its inveterate foes, the Imperium, which had raged through the rest of the Valley. The wilderness surrounding it had seen battle, he had been told, and there was the incident with farmer Renson’s barn that was turned into kindling by stray cannon fire. But by and large, the two nations kept their fighting focused on the cities and resources. A township like Littlebarrow was worthy only of a few scuffles between Revolutionary cadres and Imperial mages.

One such scuffle had deposited Sindra here two years ago. After a savage battle that saw her grievously wounded after bringing down an Imperial Graspmage, she had been left for dead by both her comrades and her foes. The people of the township had taken her in, nursed her back to health, and begged her to put her sword and strength to the defense of their township, which she, in possession of a generous heart that nonetheless burned relentlessly for justice, reluctantly agreed to.

At least, that’s the way Sindra told it.

Meret suspected the true story was perhaps less dramatic, but he let her have her stories. It was true enough that she had the injuries that came from defending the town against the occasional monster that came wandering out of the woods or outlaws that came searching for an easy hit. But if the war ever came back to this part of the Valley, a middle-aged woman with a sword wouldn’t do much to stop it.

Hell, neither would a hundred.

He’d been to the rest of the Valley. He’d seen the tanks smashed into the earth by magic, their crews buried alive inside them. He’d seen the towns and cities reduced to blackened skeletons by cannon fire. He’d seen the big graveyards and the little graveyards and the places where they just hadn’t bothered to bury the bodies and had left the bird-gnawed bones to rot where they lay.

It hadn’t put him off. After all, the wounds inflicted by that terrible war were the whole reason he had come to the Valley once the Imperium claimed victory and started settling it again. But part of him wondered if the reason he hadn’t lingered so long in Littlebarrow was because, deep down, he knew that he’d never come close to mending even a fraction of those wounds.

“I can’t pay you, you know.”

He snapped out of his reverie to see Sindra leaning over the small table—an accompaniment to the small chair, small cabinet, and small bed that were the only furnishings of her small house. Though she stared at her hands, he could see the shame on her face all the same.

“It’s not like Terassus here,” she said softly. “We don’t have rich people. I know you’ve done more for this town than we deserve, but…”

She couldn’t bring herself to finish the sentence. He couldn’t bring himself to press her.

Wounds, he’d learned, came in two kinds. If you were lucky, you got to treat the broken bones, the split-open heads, the horrible burns—wounds that herbs and bandages and sutures could fix. If you weren’t, you had to treat the wounds like the kind Sindra had, like the kind all soldiers had.

The war had left them all over the Valley: soldiers who woke each night seeing the faces of their best friends melting off their skulls, soldiers who were visited by the ghosts of people they’d strangled to death, soldiers who had seen all the fire and blood and bodies that had heaped up across the Valley and simply lay down and didn’t see a reason to get back up.

Sindra was a strong woman. If half her stories were true, one of the strongest the Revolution had seen. She had been a sword of the Revolution. But she had been left behind. Too broken to be used by her comrades.

How did you fix a sword that couldn’t kill?

Meret didn’t know. He only knew what his master had taught him: how to keep wounds from getting infected and how to set broken bones, and one important cure that almost never failed.

“Do you have cups?”

Sindra looked up, confused. “Huh?”

“Cups. Glasses. Bowls will do, if you’ve got nothing else in this dump.” He slid a hand into his satchel and pulled the whiskey out, giving it a come-hither slosh. “You want to pay me back? I just finished my rounds and I hate drinking alone.”

Sindra grinned. “Close the fucking door, then. Snow’s coming.”

He smiled, walked to the door, looked up to the clouds. She was right. Winter was coming early to the Valley, as it always did. Snow fell gently, a layer of cold, black flakes falling softly upon the town’s—

“Wait.” Meret squinted. “Black?”

Somewhere far away, beyond the thick cloying gray of the sky, he heard a sound. Like a voccaphone, he thought, that strange crackling machine warble that couldn’t ever quite sound like a human. A tune, growing louder, one he could have sworn he’d heard before. What were those lyrics? What was that song?

“Is that,” Sindra muttered to herself, glancing out the window, “the Revolutionary anthem?”

And then the sky exploded.

First, sound.

A roar split the sky apart, a wail of breaking wood and shrieking metal fighting to be heard. The gray clouds shuddered and swirled, chased away to reveal a bright red flash, as though someone had jammed a knife into the sky and cut a wound lengthwise.

Then, fire.

In cinders, in embers, in fist-sized chunks and shards as big as Meret, it fell from the sky. A splintered timber crashed in Rodic’s field and lay smoldering like a pyre. A blade of metal as long as a rothac speared through the roof of a house and belched fire through the wound it had just cleaved. All around the town, the fires fell, erupting in gouts of flame, an orchard of laughing red blossoms in the span of a soot-choked breath.

And then, the ship.

Its prow punched through the clouds, the gray parting for the great iron figurehead of a stern-looking man, his hand thrust out in defiant warning. A hull followed, riddled with wounds of black and red as fires burst out of its timbers. Propellers across its deck and prow screamed in metal agony as they came apart under the stress of the flame. For one glorious moment, the sky was alight with the beautiful view of the ship, as magnificent as any he had seen in the richest harbors across the Scar, burning as bright as a tiny sun.

And then it crashed.

Meret had the presence of mind to scream as it plummeted into the earth. If there was a god, they must have heard him, for the ship veered away from the town and smashed itself into the fields nearby, carving a blackened scar into the earth as it tore through the trees there. A cloud of smoke roiled up, sweeping through the town and casting them into blackness.

“Shit.”

He hadn’t even noticed Sindra standing beside him that whole time. She was still staring at the wound in the clouds, mouth agape despite the ash gathering on her lips.

“That was… a ship,” she whispered reverently. “A fucking airship. The Great General’s very own fleet. I remember the propaganda, the paintings they made.” She swallowed hard. “That thing’s a Revolutionary prize. They won’t let it sit here. We have to get everyone and get away from the town before they come.”

That was very good advice, Meret thought.

And had he caught the whole of it, he’d probably have agreed.

As it was, he only managed to catch about half of it before running off toward the wreckage of the site like a fucking idiot.

It was stupid, he knew. But he had been stupid to come to the Valley to help people, stupider still to become an apothecary in the first place, so he saw no reason to stop now. He slowed only to shout warnings to get clear to the curious and horrified onlookers who had gathered outside to see the sky fall. He didn’t stop until he found the first body.

He tripped over it, planting face-first into the burned dirt. He looked back and grimaced at the sight of a blue coat laden with fancy-looking medals. Treating Revolutionaries always came with risks—they tended to “thank” you for your service by conscripting you into their armies.

Fortunately, this guy was dead.

Unfortunately, it had been magic that killed him.

An icicle jutted out of his chest, as long as a man’s arm, still whispering frigid mist even as fires burned around him. Only a mage could do something like that. And there weren’t many mages who weren’t part of the Imperium. Which meant war had brought this ship here.

And this ship had brought war here.

He pulled himself to his feet and beheld the other bodies scattered like ash across the field, half hidden in the cloud of dust and grit. Most were burned to death, smoldering alongside the ship’s rubble. A few had been crushed or broken like toys, tossed when the ship had been struck. A few others were dead of more unusual circumstances. But they were all dead.

More than he’d ever seen in one spot.

“You fucker.”

A hand grabbed him by the shoulder. He whirled, fearing the Revolution had already come to claim their war machine or that the dead had risen due to some magical birdshittery. Seeing Sindra’s angry face made him think that either of those might have been preferable.

“Do you not understand what’s happening here?” she snapped. “Everyone in the Valley must have seen this ship come down. Either the Revolution will come to pick up the pieces or the Imperium will come to finish the job and both of those things end with Littlebarrow and everyone in it dead.”

“But I had to help—” Meret began weakly.

“Help what?”

Good question. There was nothing left for him here. Even if he did find survivors, what could herbs and salves do for people who had been crushed by a giant airship or electrocuted by doomlightning or whatever the fuck those mages did?

But he could still help the people of Littlebarrow. And they’d need help. Whatever else happened after this day, it would not end well.

He sighed, turned, and nodded at Sindra. She nodded back, cuffed him lightly across the head, and together they started walking.

Until the rubble started moving, anyway.

The groan of timber caught his ear. He turned and saw a pile of debris shifting. He walked toward it and, as if in response, something reached out.

A hand. Wrapped in a dirty leather glove stained with blood. Tattoos of blue-and-white cloudscapes and wings stretched from the wrist down to the elbow. It reached out of the rubble, fingers twitching.

Alive.

In need of help.

Or so Meret thought when he started to run toward it. But when he came within ten feet of the pile, it shifted suddenly. A great beam of wood rose, pushed upward by a shape shadowed in the cloud of ash. Two tattooed arms lifted the great beam and, with a grunt of effort, shoved them aside.

The smoke cleared. The fires ebbed. And Meret saw a woman standing there.

Alive.

She was tall, lean, corded with muscle that shuddered with labored breathing, her dirty leathers not making much of an effort to conceal it. Or the numerous old scars and fresh injuries she wore. An empty scabbard hung at her hip. Her hair, Imperial white and cut rudely short, was dusted with ash. Pale blue eyes stared across the field, empty.

He started to move toward her. Sindra seized him.

“No.” No anger in her voice, just quiet, desperate fear. “No, Meret. You can’t help that one.”

“Why not?”

“The tattoos. You don’t recognize them?”

He squinted at her inked forearms. “Vagrant tattoos. She’s a rebel mage?”

“Not just any, you fool,” Sindra whispered. “You haven’t heard the tales? The warnings? That’s no outlaw.”

She pointed a baleful finger at the woman.

“That’s Sal the Cacophony.”

And a cold deeper than winter wrenched his spine.

He’d heard. Everybody who ever hoped to help people in the Scar had heard of Sal the Cacophony. The woman who walked across the Scar and left misery and ruin in her wake. The woman who had killed more people, made more widows, and ended more townships than the fiercest beast or the cruelest outlaw. The woman who painted the Scar with the remains of her enemies—Vagrant, Imperial, Revolutionary…

Sal the Cacophony, it was said, had tried to kill one of everything that walked, crawled, or flew across this dark earth.

And maybe that was true. Maybe all of it was. Maybe she had done even worse things than what the stories said.

But at that moment in that ash-choked field, Meret did not think about what may be. He thought about the only two things he knew to be true.

First, he should definitely turn around, start walking, and keep going until he forgot Littlebarrow’s name.

Second, he was not going to do that.

“Meret.”

Sindra, a woman who had once screamed the whole town awake when she thought someone had touched her sword, sounded strange, whispering his name as he started walking toward the white-haired woman. She didn’t go after him, making little more than a fumbling reach for his shoulder as he headed deeper into the ash.

Sindra, who had once slain a Bittercoil Serpent by leaping into its mouth and cutting her way out, was scared to draw the notice of this woman.

Truth be told, maybe he was, too. Or maybe he thought that the closer he was to the damage, the more he could keep it from reaching Littlebarrow. Or maybe some dark part of him, the morbidly curious part that had driven him to come to this war-torn land, wanted to look into the eyes of a killer instead of a corpse.

He didn’t deal with what may be. He dealt with what he knew to be true.

Someone was injured. And he could help.

“Madam?”

His voice was so timid he barely heard himself over the mutter of nearby fires and the groan of fragmenting metal as the gunship’s remains continued to crumble. Sal the Cacophony, breathing raggedly and staring out into the distance, did not seem to notice. He came closer, spoke a little louder.

“Are you hurt?”

She didn’t look at him. She didn’t even seem to notice the fact that her immediate vicinity was almost entirely on fire. Trauma, perhaps; he’d seen it before.

“We saw the ship come down…” He glanced toward the ruin of the machine, wearily sighing plumes of flame. “I mean, everyone did.” He looked back to Sal. “What happened—”

Or, more specifically, he looked into a gun.

A polished piece of brass, its barrel forged to perfectly resemble a grinning dragon’s leer, stared at him through metal eyes. Steam peeled off the cylinder, almost as if the thing were alive and breathing. A polished hilt of black wood clung to her hand—or she to it—as she leveled the gun at his face, finger on the trigger, and pulled the hammer back with a click that carried through the sounds of hell.

Including the sound of his own heart dropping into his belly.

Meret stared into the weapon’s smile, into that black hole between its jaws. For every story about the woman, there was another one about her weapon. The Cacophony could set fires that never went out. The Cacophony warped metal and broke stone. The Cacophony sang a song so fierce it killed anyone who listened to it.

He hadn’t heard as many stories about the gun. But even if he hadn’t heard a single one, he would have believed them.

Weapons ought not to look at people.

Not like that.

“Imperial?”

A ragged voice caught his ear. He looked up the barrel to see her looking down it. Her blue eyes, no longer so distant, were fixed on him. A long scar carved its way down the right side of her face, and a cold stare punched through him just as cleanly as the gun’s brass eyes had.

“W-what?” he asked.

“You Imperial?” Sal the Cacophony asked again, with the slightest variation in tone that suggested the next time she asked, it would be to a corpse.

He shook his head. “No.”

“Revolutionary?”

“No. I’m just…” He, without taking his eyes off the gun, gestured in the direction of Littlebarrow. “I’m from the village over there. Unaffiliated. Neutral.”

She stared at him for a long moment. Slowly, her eyes slid to the gun with an expectant look, like she expected it to weigh in on whether he was lying or not.

Could it do that? Was there a story about that somewhere? He thought he had heard something like that once.

“You know this gun?” she asked.

He nodded.

“You know what it can do?”

He nodded.

“Am I going to need to use it?”

He shook his head.

She either believed him or realized that she could probably wring his neck just as easily as shoot him. The gun lowered and, with a hissing sound, slid into a sheath at her side.

Without the threat of imminent death by firearm, he had a chance to take stock of her. Her breathing was steadier and she seemed unbothered by the wounds decorating her. Was that part of her legend? he wondered. Did Sal the Cacophony simply not feel pain?

“You a healer?”

Apparently not.

He noticed her eyes on his satchel. “Y-yeah,” he said, opening it. “I’ve got salves and… and stuff.” He swallowed hard, looked over her wounds. “What sort of pain are you feeling and when—”

“Not me.”

He looked up. She stepped away, pointed down to the earth.

“Her.”

There, nestled amid the wreckage, was a woman.

Pale, slender, dressed in clothes that weren’t Revolutionary, weren’t Imperial, weren’t anything special. Her black hair hung limp around a face peppered with cuts and scratches. Her skirts were torn and her shirt was stained with blood and soot. A pair of shattered spectacles rested on her chest.

She didn’t look like a Vagrant. Or anything that the stories said Sal the Cacophony was interested in. She was just a woman. A plain, ordinary woman you might find in a plain, ordinary place like Littlebarrow.

Why, Meret wondered, would a monster like Sal the Cacophony be around her?

“Help her.”

A good question. One he’d answer someday, if he had the time. But that would be another day, another place, another person. Right now, he was here, the only one who could help.

He knelt down beside the pale girl. He performed all the tests he had been taught: moved her as gently as he dared, listened to her breathing, studied her many cuts. He did not look back up to Sal the Cacophony, did not dare give her hope. Whatever monster she was, right now she was like any of the other fretting people who doted over their injured. She did not need hope. She needed information.

He could give it to her.

“Her breathing’s difficult,” he muttered. “Probably not surprising, given the fall. But it’s dry. No internal bleeding that I can tell.” He looked down at her leg and winced. “Thighbone is broken. Her left arm, too. And I’d be shocked if that was all.” He dusted the considerable amount of ash that had gathered on his clothes as he rose. “And that’s without however many cuts and wounds she’s got.”

“Can you help her?”

When he turned to face Sal the Cacophony, her stare was no longer so distant, nor quite so cold. It was soft. Wet. It didn’t belong on a monster. It didn’t belong in a place like this.

“Tell me what happened here,” he said, “and maybe.”

Those eyes hardened. Cold and thin as scalpels in a corpse’s body. She spoke in the voice of someone who was used to speaking once and did not repeat herself without steel to accompany it.

“You don’t need to know that,” she said, as slow and calm as a sword pulled out of a ten-days-dead body. “Help her. Help yourself.”

Despite the flames, he froze. His legs turned to jelly. His breath left him and was replaced by something weak and rotten in his lungs. He hadn’t felt that wind, that cold, since the day he had come to the Valley and seen the bodies.

He hadn’t turned away then, either.

“N-no,” he said.

“What?”

“No.” He forced his voice hard, his spine straight, his eyes on hers. “Whatever happened here, it concerns this town. And if it concerns this town, it concerns me.” He swallowed lead. “I’ll help her. But you have to tell me.”

She stared at him. Did the stories say she never blinked or had he just made that up?

She raised a hand. He forced himself not to look away.

Her hand shot out toward his waist. He felt ice in his belly, terrified that he’d look down and see a blade jutting out of him. His breath left him as she slowly drew her hand back.

In it, she held the bottle of whiskey he packed.

“Avonin.” Her eyes widened a little. “Damn, kid. What do you use this for?”

“Disinfecting wounds,” he replied.

She looked at him like he had just insulted her mother, then gestured at the unconscious woman with her chin.

“How much of this do you need to treat her?”

“I… I don’t know. Half, I think?”

“You sure?”

“No.”

“Get sure.”

He looked over the woman on the ground, nodded. “Half.”

Sal the Cacophony nodded back. Then she pried the cork out with her teeth, spat it out, and upended the bottle into her mouth and did not stop to breathe until she had drained exactly half the bottle.

She handed it back to him, licked her lips, and spat on the ground.

“I’ll tell you,” she said, “but you have to promise me something.”

He stared at her as she looked over the wreckage. “All right.”

“I won’t ask you to promise to forgive me,” she said. “But when I’m done…”

She closed her eyes, sheathed her weapon, and let a black breeze blow over her.

“Promise me you’ll try.”

Anyway, what was I talking about?

Oh, right.

The massacre.

It took me a second to notice through the blood weeping down into my eye, but his guard had dropped. Weary arms could no longer hold his blade quite so high, the tip of it dragging in the earth as he charged toward me, a scream tearing out of his throat, dust rising in a cloud behind him.

“DIE, CACOPHONY!”

He roared, swinging his sword up as he came within spitting distance. I stepped around the blade, into his path, bringing my own blade up. Steel flashed. A splash of red stained the air. His sword rushed past me, biting into my cheek and drawing blood.

As for my sword…

His body stiffened on my blade. His eyes were frozen in unblinking horror, yet he couldn’t look down to see the four inches of steel thrust into his belly. His lips trembled, struggling to find his last words, to make them meaningful. I have no idea if they were or not. When he spoke them, they came out on a bubbling river of blood that spilled out of his mouth and onto the dirt.

Where he fell, three seconds later, after I pulled my weapon free.

And there he lay, unmoving. Another dark stain on another patch of dark earth.

Just like the other four.

Once the air stopped ringing with steel and screams, I let my blade lower. My breath came out hot and my saliva came out red. My spittle fell and lay on the cheek of a woman’s body, but I didn’t think she’d mind—after all, it wasn’t the worst thing I had done to her. To any of them.

I’d given them every opportunity. I came wandering into their valley, my blade naked in my hand and my arms open and waiting. I came screaming my own name and cursing theirs. I came with no surprises, no stealth, no subtlety—just a sword and harsh language. And they were dead.

And I was still alive.

Assholes.

Credit where it’s due, they’d given it their best shot. My body was littered with cuts—grazes, a few gashes, one good gouge that I thought might have ended it—but the blood drying in the cold mountain air on my chest was mostly not my own. My breath was coming harsh in my lungs. My scars ached, my bones ached, my body ached. But it wasn’t ready to quit.

Which meant I still had a mage to kill.

I heard the click of a trigger, the thrum of a crossbow string, and the shriek of a bolt. I glanced up. A bolt as long as my arm flew past my head, jamming itself into a dead tree ten feet away.

I stared down a long stretch of dark earth. The young man holding an empty arbalest far too big for him stared back at me, dumbfounded. I sniffed, wiped blood from my cheek.

“Shit, kid,” I said. “I was standing still. I didn’t even see you. And you still missed.” I gestured to my body, spattered with the drying life of his comrades. “Do you need me to get closer?”

I started walking toward him, my sword hanging heavy in my hand. Then I started jogging. Only once I saw him grab a bolt did I start running.

He ceased to be a person and became a series of fumbles—fumbling lips struggling to find a word, fumbling hands struggling to load the arbalest. If I had waited long enough, he might hav

Meret awoke before the dawn, as he always did, to grind the herbs he had dried last week into tinctures and salves that would cure by next week. He gathered the medicines he needed to, as he always did—balm for Rodic’s burn that he had gotten at the smithy, salve for old man Erton’s bad knee, and as always, a bottle of Avonin whiskey for whatever might arise in the day—put them into his bag, and set out. He made his rounds, as he always did, and visited the same patients he always had since he had arrived in Littlebarrow three months ago.

The name was a little unfair, he thought. After all, it was a long time ago that a woman had built a shack to live in beside the cairn she had constructed for her only child. Since then, enough people had found it a good place to stop on sojourns into the Valley that it had grown to a township worthier of a name that matched its thriving circumstances. But as it wasn’t his township, he thought it not his place to protest the name, no matter how much he had grown attached to the place.

While it was nowhere near as big as Terassus or even the larger towns in the Valley, and it still had its share of problems, Littlebarrow was one of the better places his training had taken him. The people were nice, the winter was relatively gentle, and the surrounding forest was thick enough for game but not so much that larger beasts would come sniffing around.

Littlebarrow was a fine place. And Meret liked to think he had helped.

“Fuck me, boy, you missed your true calling as a torturer.”

Not everyone agreed.

He glanced up from Sindra’s knee, now wrapped in fresh antiseptic-soaked bandages, to Sindra’s face, contorted in pain, with keen distaste that he hoped his glasses magnified enough to demonstrate how tired he was of that joke.

“And you apparently misheard yours,” he said to his newest patient. “I would have thought a soldier would be made of sterner stuff.”

“If my name were Sindra Stern, I’d agree,” the woman growled. “As the Great General saw fit to call me Sindra Honest, I’ll do you the courtesy of pointing out that this shit”—she gestured to the bandages—“fucking hurts.”

“It hurts much less than the infection the salve keeps out, I assure you,” Meret replied, cinching the bandage tight. He dared to flash a wry grin at the woman. “And you were warned about the importance of keeping the joint clean, so in the interests of honesty, I believe I could say I told you so?”

Sindra’s glare loitered on him for an uncomfortable second before she lowered her gaze to her knee. And as her eyes followed the length of her leg, her glare turned to a frown.

The bandages marked the end of her flesh and the beginning of the metal-and-wood prosthetic that had been attached months ago. She rolled its ankle, as if still unconvinced that it was real, and a small series of sigils let off a faint glow in response.

“Fucking magic,” she said with a sneer. “Still not sure that I wouldn’t be better off with just one leg.”

“I’m sure you wouldn’t be able to help as many people without it,” Meret added. “And the spellwrighting that made it possible isn’t technically magic.”

“I was a Revolutionary, boy,” Sindra said with a sneer as she pulled her trouser leg over the prosthesis. “I know fucking magic when I fucking see it.”

“I thought that the soldiers of the Grand Revolution of the Fist and Flame were so pure of ideal that vulgar language never crossed their lips.”

Sindra’s face, dark-skinned and bearing the stress wrinkles of a woman much older than she actually was, was marred by a sour frown. It matched the rest of her body at least. Broad shoulders and thick arms that her old military shirt had long given up trying to hide were corded with the thick muscle that comes from hard labor, hard battles, and harder foes. Her hair was prematurely gray, her boot was prematurely thin, and her heart was prematurely disillusioned. The only part of her that wasn’t falling apart was the sword hanging from her hip.

That, she kept as sharp as her tongue.

“It’s the Glorious Revolution, you little shit,” she muttered, “and it’s a good thing I’m not in it anymore, isn’t it?”

“True,” Meret hummed. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to treat you.”

“Yeah, lucky fucking me,” Sindra grumbled. “I wouldn’t mind a couple of alchemics our cadre medics used to have, though. A hit of those and I could fight all night.”

“I am but a humble apothecary, madam,” he replied. “And while herbs and bandages take longer, they heal just as good.”

Sindra sighed as she winced and hauled herself to her feet, her prosthesis creaking as she did. “You’re just lucky that it’s a choice between keeping you around and keeping soldiers around. If it were a choice between a smart-mouthed apothecary who couldn’t heal for shit and, say, a Hornbrow who hadn’t eaten in days, I’d slather myself in sauce and pry its jaws open myself.”

He agreed, but kept it to himself.

Littlebarrow had been fortunate enough to escape most of the battles between the Revolution and its inveterate foes, the Imperium, which had raged through the rest of the Valley. The wilderness surrounding it had seen battle, he had been told, and there was the incident with farmer Renson’s barn that was turned into kindling by stray cannon fire. But by and large, the two nations kept their fighting focused on the cities and resources. A township like Littlebarrow was worthy only of a few scuffles between Revolutionary cadres and Imperial mages.

One such scuffle had deposited Sindra here two years ago. After a savage battle that saw her grievously wounded after bringing down an Imperial Graspmage, she had been left for dead by both her comrades and her foes. The people of the township had taken her in, nursed her back to health, and begged her to put her sword and strength to the defense of their township, which she, in possession of a generous heart that nonetheless burned relentlessly for justice, reluctantly agreed to.

At least, that’s the way Sindra told it.

Meret suspected the true story was perhaps less dramatic, but he let her have her stories. It was true enough that she had the injuries that came from defending the town against the occasional monster that came wandering out of the woods or outlaws that came searching for an easy hit. But if the war ever came back to this part of the Valley, a middle-aged woman with a sword wouldn’t do much to stop it.

Hell, neither would a hundred.

He’d been to the rest of the Valley. He’d seen the tanks smashed into the earth by magic, their crews buried alive inside them. He’d seen the towns and cities reduced to blackened skeletons by cannon fire. He’d seen the big graveyards and the little graveyards and the places where they just hadn’t bothered to bury the bodies and had left the bird-gnawed bones to rot where they lay.

It hadn’t put him off. After all, the wounds inflicted by that terrible war were the whole reason he had come to the Valley once the Imperium claimed victory and started settling it again. But part of him wondered if the reason he hadn’t lingered so long in Littlebarrow was because, deep down, he knew that he’d never come close to mending even a fraction of those wounds.

“I can’t pay you, you know.”

He snapped out of his reverie to see Sindra leaning over the small table—an accompaniment to the small chair, small cabinet, and small bed that were the only furnishings of her small house. Though she stared at her hands, he could see the shame on her face all the same.

“It’s not like Terassus here,” she said softly. “We don’t have rich people. I know you’ve done more for this town than we deserve, but…”

She couldn’t bring herself to finish the sentence. He couldn’t bring himself to press her.

Wounds, he’d learned, came in two kinds. If you were lucky, you got to treat the broken bones, the split-open heads, the horrible burns—wounds that herbs and bandages and sutures could fix. If you weren’t, you had to treat the wounds like the kind Sindra had, like the kind all soldiers had.

The war had left them all over the Valley: soldiers who woke each night seeing the faces of their best friends melting off their skulls, soldiers who were visited by the ghosts of people they’d strangled to death, soldiers who had seen all the fire and blood and bodies that had heaped up across the Valley and simply lay down and didn’t see a reason to get back up.

Sindra was a strong woman. If half her stories were true, one of the strongest the Revolution had seen. She had been a sword of the Revolution. But she had been left behind. Too broken to be used by her comrades.

How did you fix a sword that couldn’t kill?

Meret didn’t know. He only knew what his master had taught him: how to keep wounds from getting infected and how to set broken bones, and one important cure that almost never failed.

“Do you have cups?”

Sindra looked up, confused. “Huh?”

“Cups. Glasses. Bowls will do, if you’ve got nothing else in this dump.” He slid a hand into his satchel and pulled the whiskey out, giving it a come-hither slosh. “You want to pay me back? I just finished my rounds and I hate drinking alone.”

Sindra grinned. “Close the fucking door, then. Snow’s coming.”

He smiled, walked to the door, looked up to the clouds. She was right. Winter was coming early to the Valley, as it always did. Snow fell gently, a layer of cold, black flakes falling softly upon the town’s—

“Wait.” Meret squinted. “Black?”

Somewhere far away, beyond the thick cloying gray of the sky, he heard a sound. Like a voccaphone, he thought, that strange crackling machine warble that couldn’t ever quite sound like a human. A tune, growing louder, one he could have sworn he’d heard before. What were those lyrics? What was that song?

“Is that,” Sindra muttered to herself, glancing out the window, “the Revolutionary anthem?”

And then the sky exploded.

First, sound.

A roar split the sky apart, a wail of breaking wood and shrieking metal fighting to be heard. The gray clouds shuddered and swirled, chased away to reveal a bright red flash, as though someone had jammed a knife into the sky and cut a wound lengthwise.

Then, fire.

In cinders, in embers, in fist-sized chunks and shards as big as Meret, it fell from the sky. A splintered timber crashed in Rodic’s field and lay smoldering like a pyre. A blade of metal as long as a rothac speared through the roof of a house and belched fire through the wound it had just cleaved. All around the town, the fires fell, erupting in gouts of flame, an orchard of laughing red blossoms in the span of a soot-choked breath.

And then, the ship.

Its prow punched through the clouds, the gray parting for the great iron figurehead of a stern-looking man, his hand thrust out in defiant warning. A hull followed, riddled with wounds of black and red as fires burst out of its timbers. Propellers across its deck and prow screamed in metal agony as they came apart under the stress of the flame. For one glorious moment, the sky was alight with the beautiful view of the ship, as magnificent as any he had seen in the richest harbors across the Scar, burning as bright as a tiny sun.

And then it crashed.

Meret had the presence of mind to scream as it plummeted into the earth. If there was a god, they must have heard him, for the ship veered away from the town and smashed itself into the fields nearby, carving a blackened scar into the earth as it tore through the trees there. A cloud of smoke roiled up, sweeping through the town and casting them into blackness.

“Shit.”

He hadn’t even noticed Sindra standing beside him that whole time. She was still staring at the wound in the clouds, mouth agape despite the ash gathering on her lips.

“That was… a ship,” she whispered reverently. “A fucking airship. The Great General’s very own fleet. I remember the propaganda, the paintings they made.” She swallowed hard. “That thing’s a Revolutionary prize. They won’t let it sit here. We have to get everyone and get away from the town before they come.”

That was very good advice, Meret thought.

And had he caught the whole of it, he’d probably have agreed.

As it was, he only managed to catch about half of it before running off toward the wreckage of the site like a fucking idiot.

It was stupid, he knew. But he had been stupid to come to the Valley to help people, stupider still to become an apothecary in the first place, so he saw no reason to stop now. He slowed only to shout warnings to get clear to the curious and horrified onlookers who had gathered outside to see the sky fall. He didn’t stop until he found the first body.

He tripped over it, planting face-first into the burned dirt. He looked back and grimaced at the sight of a blue coat laden with fancy-looking medals. Treating Revolutionaries always came with risks—they tended to “thank” you for your service by conscripting you into their armies.

Fortunately, this guy was dead.

Unfortunately, it had been magic that killed him.

An icicle jutted out of his chest, as long as a man’s arm, still whispering frigid mist even as fires burned around him. Only a mage could do something like that. And there weren’t many mages who weren’t part of the Imperium. Which meant war had brought this ship here.

And this ship had brought war here.

He pulled himself to his feet and beheld the other bodies scattered like ash across the field, half hidden in the cloud of dust and grit. Most were burned to death, smoldering alongside the ship’s rubble. A few had been crushed or broken like toys, tossed when the ship had been struck. A few others were dead of more unusual circumstances. But they were all dead.

More than he’d ever seen in one spot.

“You fucker.”

A hand grabbed him by the shoulder. He whirled, fearing the Revolution had already come to claim their war machine or that the dead had risen due to some magical birdshittery. Seeing Sindra’s angry face made him think that either of those might have been preferable.

“Do you not understand what’s happening here?” she snapped. “Everyone in the Valley must have seen this ship come down. Either the Revolution will come to pick up the pieces or the Imperium will come to finish the job and both of those things end with Littlebarrow and everyone in it dead.”

“But I had to help—” Meret began weakly.

“Help what?”

Good question. There was nothing left for him here. Even if he did find survivors, what could herbs and salves do for people who had been crushed by a giant airship or electrocuted by doomlightning or whatever the fuck those mages did?

But he could still help the people of Littlebarrow. And they’d need help. Whatever else happened after this day, it would not end well.

He sighed, turned, and nodded at Sindra. She nodded back, cuffed him lightly across the head, and together they started walking.

Until the rubble started moving, anyway.

The groan of timber caught his ear. He turned and saw a pile of debris shifting. He walked toward it and, as if in response, something reached out.

A hand. Wrapped in a dirty leather glove stained with blood. Tattoos of blue-and-white cloudscapes and wings stretched from the wrist down to the elbow. It reached out of the rubble, fingers twitching.

Alive.

In need of help.

Or so Meret thought when he started to run toward it. But when he came within ten feet of the pile, it shifted suddenly. A great beam of wood rose, pushed upward by a shape shadowed in the cloud of ash. Two tattooed arms lifted the great beam and, with a grunt of effort, shoved them aside.

The smoke cleared. The fires ebbed. And Meret saw a woman standing there.

Alive.

She was tall, lean, corded with muscle that shuddered with labored breathing, her dirty leathers not making much of an effort to conceal it. Or the numerous old scars and fresh injuries she wore. An empty scabbard hung at her hip. Her hair, Imperial white and cut rudely short, was dusted with ash. Pale blue eyes stared across the field, empty.

He started to move toward her. Sindra seized him.

“No.” No anger in her voice, just quiet, desperate fear. “No, Meret. You can’t help that one.”

“Why not?”

“The tattoos. You don’t recognize them?”

He squinted at her inked forearms. “Vagrant tattoos. She’s a rebel mage?”

“Not just any, you fool,” Sindra whispered. “You haven’t heard the tales? The warnings? That’s no outlaw.”

She pointed a baleful finger at the woman.

“That’s Sal the Cacophony.”

And a cold deeper than winter wrenched his spine.

He’d heard. Everybody who ever hoped to help people in the Scar had heard of Sal the Cacophony. The woman who walked across the Scar and left misery and ruin in her wake. The woman who had killed more people, made more widows, and ended more townships than the fiercest beast or the cruelest outlaw. The woman who painted the Scar with the remains of her enemies—Vagrant, Imperial, Revolutionary…

Sal the Cacophony, it was said, had tried to kill one of everything that walked, crawled, or flew across this dark earth.

And maybe that was true. Maybe all of it was. Maybe she had done even worse things than what the stories said.

But at that moment in that ash-choked field, Meret did not think about what may be. He thought about the only two things he knew to be true.

First, he should definitely turn around, start walking, and keep going until he forgot Littlebarrow’s name.

Second, he was not going to do that.

“Meret.”

Sindra, a woman who had once screamed the whole town awake when she thought someone had touched her sword, sounded strange, whispering his name as he started walking toward the white-haired woman. She didn’t go after him, making little more than a fumbling reach for his shoulder as he headed deeper into the ash.

Sindra, who had once slain a Bittercoil Serpent by leaping into its mouth and cutting her way out, was scared to draw the notice of this woman.

Truth be told, maybe he was, too. Or maybe he thought that the closer he was to the damage, the more he could keep it from reaching Littlebarrow. Or maybe some dark part of him, the morbidly curious part that had driven him to come to this war-torn land, wanted to look into the eyes of a killer instead of a corpse.

He didn’t deal with what may be. He dealt with what he knew to be true.

Someone was injured. And he could help.

“Madam?”

His voice was so timid he barely heard himself over the mutter of nearby fires and the groan of fragmenting metal as the gunship’s remains continued to crumble. Sal the Cacophony, breathing raggedly and staring out into the distance, did not seem to notice. He came closer, spoke a little louder.

“Are you hurt?”

She didn’t look at him. She didn’t even seem to notice the fact that her immediate vicinity was almost entirely on fire. Trauma, perhaps; he’d seen it before.

“We saw the ship come down…” He glanced toward the ruin of the machine, wearily sighing plumes of flame. “I mean, everyone did.” He looked back to Sal. “What happened—”

Or, more specifically, he looked into a gun.

A polished piece of brass, its barrel forged to perfectly resemble a grinning dragon’s leer, stared at him through metal eyes. Steam peeled off the cylinder, almost as if the thing were alive and breathing. A polished hilt of black wood clung to her hand—or she to it—as she leveled the gun at his face, finger on the trigger, and pulled the hammer back with a click that carried through the sounds of hell.

Including the sound of his own heart dropping into his belly.

Meret stared into the weapon’s smile, into that black hole between its jaws. For every story about the woman, there was another one about her weapon. The Cacophony could set fires that never went out. The Cacophony warped metal and broke stone. The Cacophony sang a song so fierce it killed anyone who listened to it.

He hadn’t heard as many stories about the gun. But even if he hadn’t heard a single one, he would have believed them.

Weapons ought not to look at people.

Not like that.

“Imperial?”

A ragged voice caught his ear. He looked up the barrel to see her looking down it. Her blue eyes, no longer so distant, were fixed on him. A long scar carved its way down the right side of her face, and a cold stare punched through him just as cleanly as the gun’s brass eyes had.

“W-what?” he asked.

“You Imperial?” Sal the Cacophony asked again, with the slightest variation in tone that suggested the next time she asked, it would be to a corpse.

He shook his head. “No.”

“Revolutionary?”

“No. I’m just…” He, without taking his eyes off the gun, gestured in the direction of Littlebarrow. “I’m from the village over there. Unaffiliated. Neutral.”

She stared at him for a long moment. Slowly, her eyes slid to the gun with an expectant look, like she expected it to weigh in on whether he was lying or not.

Could it do that? Was there a story about that somewhere? He thought he had heard something like that once.

“You know this gun?” she asked.

He nodded.

“You know what it can do?”

He nodded.

“Am I going to need to use it?”

He shook his head.

She either believed him or realized that she could probably wring his neck just as easily as shoot him. The gun lowered and, with a hissing sound, slid into a sheath at her side.

Without the threat of imminent death by firearm, he had a chance to take stock of her. Her breathing was steadier and she seemed unbothered by the wounds decorating her. Was that part of her legend? he wondered. Did Sal the Cacophony simply not feel pain?

“You a healer?”

Apparently not.

He noticed her eyes on his satchel. “Y-yeah,” he said, opening it. “I’ve got salves and… and stuff.” He swallowed hard, looked over her wounds. “What sort of pain are you feeling and when—”

“Not me.”

He looked up. She stepped away, pointed down to the earth.

“Her.”

There, nestled amid the wreckage, was a woman.

Pale, slender, dressed in clothes that weren’t Revolutionary, weren’t Imperial, weren’t anything special. Her black hair hung limp around a face peppered with cuts and scratches. Her skirts were torn and her shirt was stained with blood and soot. A pair of shattered spectacles rested on her chest.

She didn’t look like a Vagrant. Or anything that the stories said Sal the Cacophony was interested in. She was just a woman. A plain, ordinary woman you might find in a plain, ordinary place like Littlebarrow.

Why, Meret wondered, would a monster like Sal the Cacophony be around her?

“Help her.”

A good question. One he’d answer someday, if he had the time. But that would be another day, another place, another person. Right now, he was here, the only one who could help.

He knelt down beside the pale girl. He performed all the tests he had been taught: moved her as gently as he dared, listened to her breathing, studied her many cuts. He did not look back up to Sal the Cacophony, did not dare give her hope. Whatever monster she was, right now she was like any of the other fretting people who doted over their injured. She did not need hope. She needed information.

He could give it to her.

“Her breathing’s difficult,” he muttered. “Probably not surprising, given the fall. But it’s dry. No internal bleeding that I can tell.” He looked down at her leg and winced. “Thighbone is broken. Her left arm, too. And I’d be shocked if that was all.” He dusted the considerable amount of ash that had gathered on his clothes as he rose. “And that’s without however many cuts and wounds she’s got.”

“Can you help her?”

When he turned to face Sal the Cacophony, her stare was no longer so distant, nor quite so cold. It was soft. Wet. It didn’t belong on a monster. It didn’t belong in a place like this.

“Tell me what happened here,” he said, “and maybe.”

Those eyes hardened. Cold and thin as scalpels in a corpse’s body. She spoke in the voice of someone who was used to speaking once and did not repeat herself without steel to accompany it.

“You don’t need to know that,” she said, as slow and calm as a sword pulled out of a ten-days-dead body. “Help her. Help yourself.”

Despite the flames, he froze. His legs turned to jelly. His breath left him and was replaced by something weak and rotten in his lungs. He hadn’t felt that wind, that cold, since the day he had come to the Valley and seen the bodies.

He hadn’t turned away then, either.

“N-no,” he said.

“What?”

“No.” He forced his voice hard, his spine straight, his eyes on hers. “Whatever happened here, it concerns this town. And if it concerns this town, it concerns me.” He swallowed lead. “I’ll help her. But you have to tell me.”

She stared at him. Did the stories say she never blinked or had he just made that up?

She raised a hand. He forced himself not to look away.

Her hand shot out toward his waist. He felt ice in his belly, terrified that he’d look down and see a blade jutting out of him. His breath left him as she slowly drew her hand back.

In it, she held the bottle of whiskey he packed.

“Avonin.” Her eyes widened a little. “Damn, kid. What do you use this for?”

“Disinfecting wounds,” he replied.

She looked at him like he had just insulted her mother, then gestured at the unconscious woman with her chin.

“How much of this do you need to treat her?”

“I… I don’t know. Half, I think?”

“You sure?”

“No.”

“Get sure.”

He looked over the woman on the ground, nodded. “Half.”

Sal the Cacophony nodded back. Then she pried the cork out with her teeth, spat it out, and upended the bottle into her mouth and did not stop to breathe until she had drained exactly half the bottle.

She handed it back to him, licked her lips, and spat on the ground.

“I’ll tell you,” she said, “but you have to promise me something.”

He stared at her as she looked over the wreckage. “All right.”

“I won’t ask you to promise to forgive me,” she said. “But when I’m done…”

She closed her eyes, sheathed her weapon, and let a black breeze blow over her.

“Promise me you’ll try.”

Anyway, what was I talking about?

Oh, right.

The massacre.

It took me a second to notice through the blood weeping down into my eye, but his guard had dropped. Weary arms could no longer hold his blade quite so high, the tip of it dragging in the earth as he charged toward me, a scream tearing out of his throat, dust rising in a cloud behind him.

“DIE, CACOPHONY!”

He roared, swinging his sword up as he came within spitting distance. I stepped around the blade, into his path, bringing my own blade up. Steel flashed. A splash of red stained the air. His sword rushed past me, biting into my cheek and drawing blood.

As for my sword…

His body stiffened on my blade. His eyes were frozen in unblinking horror, yet he couldn’t look down to see the four inches of steel thrust into his belly. His lips trembled, struggling to find his last words, to make them meaningful. I have no idea if they were or not. When he spoke them, they came out on a bubbling river of blood that spilled out of his mouth and onto the dirt.

Where he fell, three seconds later, after I pulled my weapon free.

And there he lay, unmoving. Another dark stain on another patch of dark earth.

Just like the other four.

Once the air stopped ringing with steel and screams, I let my blade lower. My breath came out hot and my saliva came out red. My spittle fell and lay on the cheek of a woman’s body, but I didn’t think she’d mind—after all, it wasn’t the worst thing I had done to her. To any of them.

I’d given them every opportunity. I came wandering into their valley, my blade naked in my hand and my arms open and waiting. I came screaming my own name and cursing theirs. I came with no surprises, no stealth, no subtlety—just a sword and harsh language. And they were dead.

And I was still alive.

Assholes.

Credit where it’s due, they’d given it their best shot. My body was littered with cuts—grazes, a few gashes, one good gouge that I thought might have ended it—but the blood drying in the cold mountain air on my chest was mostly not my own. My breath was coming harsh in my lungs. My scars ached, my bones ached, my body ached. But it wasn’t ready to quit.

Which meant I still had a mage to kill.

I heard the click of a trigger, the thrum of a crossbow string, and the shriek of a bolt. I glanced up. A bolt as long as my arm flew past my head, jamming itself into a dead tree ten feet away.

I stared down a long stretch of dark earth. The young man holding an empty arbalest far too big for him stared back at me, dumbfounded. I sniffed, wiped blood from my cheek.

“Shit, kid,” I said. “I was standing still. I didn’t even see you. And you still missed.” I gestured to my body, spattered with the drying life of his comrades. “Do you need me to get closer?”

I started walking toward him, my sword hanging heavy in my hand. Then I started jogging. Only once I saw him grab a bolt did I start running.

He ceased to be a person and became a series of fumbles—fumbling lips struggling to find a word, fumbling hands struggling to load the arbalest. If I had waited long enough, he might hav

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved