- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

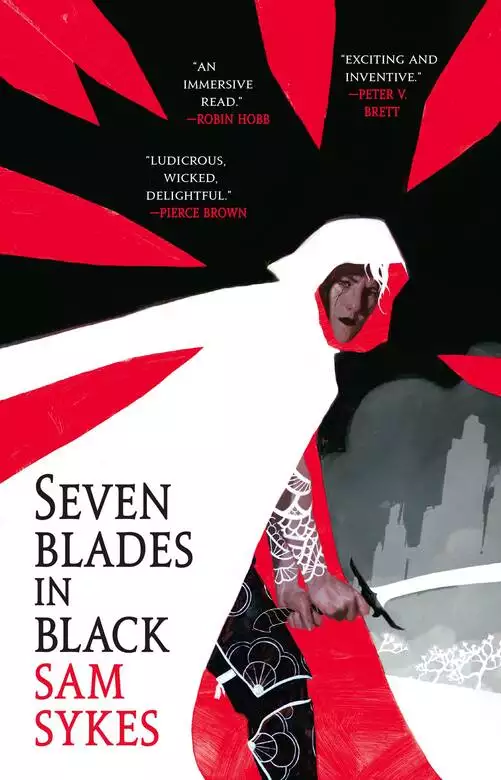

Acclaimed author Sam Sykes returns with a brilliant new epic fantasy that introduces to an unforgettable outcast magician caught between two warring empires.

Set in the Scar, where the magical, decadent Imperium battles the upstart, technologically-savvy Revolution, Seven Blades of Black follows the exploits of Sal the Cacophony, the most famous and dangerous of all the rogue mages.

Among humans, none have power like mages. And among mages, none have will like Sal the Cacophony. Once revered, now vagrant, she walks a wasteland scarred by generations of magical warfare.

The Scar, a land torn between powerful empires, is where rogue mages go to disappear, disgraced soldiers go to die and Sal went with a blade, a gun and a list of names she intended to use both on.

But vengeance is a flame swift extinguished. Betrayed by those she trusted most, her magic torn from her and awaiting execution, Sal the Cacophony has one last tale to tell before they take her head. All she has left is her name, her story and the weapon she used to carve both. Vengeance is its own reward.

Release date: April 9, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 704

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Seven Blades in Black

Sam Sykes

From the walls of Imperial Cathama to the farthest reach of the Revolution, there was no citizen of the Scar who could think of a finer way to spend an afternoon than watching the walls get painted with bits of dissidents. And behind the walls of Revolutionary Hightower that day, there was an electricity in the air felt by every citizen.

Crowds gathered to watch the dirt, still damp from yesterday’s execution, be swept away from the stake. The firing squad sat nearby, polishing their gunpikes and placing bets on who would hit the heart of the poor asshole who got tied up today. Merchants barked nearby, selling everything from refreshments to souvenirs so people could remember this day where everyone got off work for a few short hours to see another enemy of the Revolution be strung up and gunned down.

Not like there was a hell of a lot else to do in Hightower lately.

For her part, Governor-Militant Tretta Stern did her best to ignore all of it: the crowds gathering beneath her window outside the prison, their voices crowing for blood, the wailing children and the laughing men. She kept her focus on the image in the mirror as she straightened her uniform’s blue coat. Civilians could be excused such craven bloodlust. Officers of the Revolution answered a higher call.

Her black hair, severely short-cropped and oiled against her head, was befitting an officer. Jacket cinched tight, trousers pressed and belted, saber at her hip, all without a trace of dust, lint, or rust. And most crucially, the face that had sent a hundred foes to the grave with a word stared back at her, unflinching.

One might wonder what the point in getting dressed up for an execution was; after all, it wasn’t like the criminal scum who would be buried in a shallow grave in six hours would give a shit. But being an officer of the Revolution meant upholding certain standards. And Tretta hadn’t earned her post by being slack.

She took a moment to adjust the medals on her lapel before leaving her quarters. Two guards fired off crisp salutes before straightening their gunpikes and marching exactly three rigid paces behind her. Morning sunlight poured in through the windows as they marched down the stairs to Cadre Command. Guards and officers alike called to attention at her passing, raising arms as they saluted. She offered a cursory nod in response, bidding them at ease as she made her way to the farthest door of the room.

The guard stationed there glanced up. “Governor-Militant,” he acknowledged, saluting.

“Sergeant,” Tretta replied. “How have you found the prisoner?”

“Recalcitrant and disrespectful,” he said. “The prisoner began the morning by hurling the assigned porridge at the guard detail, spewing several obscenities, and making forceful suggestions as to the professional and personal conduct of the guard’s mother.” He sniffed, lip curling. “In summation, more or less what we’d expect from a Vagrant.”

Tretta spared an impressed look. Considering the situation, she had expected much worse.

She made a gesture. The guard complied, unlocking the massive iron door and pushing it open. She and her escorts descended into the darkness of Hightower’s prison, and the silence of empty cells greeted her.

Like all Revolutionary outposts, Hightower had been built to accommodate prisoners: Imperium aggressors, counterrevolutionaries, bandit outlaws, and even the occasional Vagrant. Unlike most Revolutionary outposts, Hightower was far away from any battleground in the Scar and didn’t see much use for its cells. Any captive outlaw tended to be executed in fairly short order for crimes against the Revolution, as the civilians tended to become restless without the entertainment.

In all her time stationed at Hightower, Tretta had visited the prison exactly twice, including today. The first time had been to offer an Imperium spy posing as a bandit clemency in exchange for information. Thirty minutes later, she put him in front of the firing squad. Up until then, he’d been the longest-serving captive in Hightower.

Thus far, her current prisoner had broken the record by two days.

The interrogation room lay at the very end of the row of cells, another iron door flanked by two guards. Both fired off a salute as they pulled open the door, its hinges groaning.

Twenty feet by twenty feet, possessed of nothing more than a table with two chairs and a narrow slit of a window by which to catch a beam of light, the interrogation room was little more than a slightly larger cell with a slightly nicer door. The window, set high up near the ceiling, afforded no ventilation and the room was stifling hot.

Not that you’d know it from looking at the prisoner.

A woman—perhaps in her late twenties, Tretta suspected—sat at one end of the table. Dressed in dirty trousers and boots to match, the sleeves and hem of her white shirt cut to bare the tattoos racing down her forearms and most of the great scar that wended its way from her collarbone down to her belly; it was the sort of garish garb you’d expect to find on a Vagrant. Her hair, Imperial white, was shorn roughly on the sides and tied back in an unruly tail. And despite the suffocating heat, she was calm, serene, and pale as ice.

There was nothing about this woman that Tretta didn’t despise.

She didn’t look up as the Governor-Militant entered, paid no heed to the pair of armed men trailing behind her. Her hands, manacled together, rested patiently atop the table. Even when Tretta took a seat across from her, she hardly seemed to notice. The prisoner’s eyes, pale and as blue as shallow water, seemed to be looking somewhere else. Her face, thin and sharp and marred by a long scar over her right eye, seemed unperturbed by her imminent gruesome death.

That galled Tretta more than she would have liked to admit.

The Governor-Militant leaned forward, steepling her fingers in front of her, giving the woman a chance to realize what a world of shit she was in. But after a minute of silence, she merely held out one hand. A sheaf of papers appeared there a moment later, thrust forward by one of her guards. She laid it out before her and idly flipped through it.

“I won’t tell you that you can save yourself,” she said after a time. “An officer of the Revolution speaks only truths.” She glanced up at the woman, who did not react. “Within six hours, you’ll be executed for crimes against the Glorious Revolution of the Fist and Flame. Nothing you can say will change this fact. You deserve to die for your crimes.” She narrowed her eyes. “And you will.”

The woman, at last, reacted. Her manacles rattled a little as she reached up and scratched at the scars on her face.

Tretta sneered and continued. “What you can change,” she said, “is how quickly it goes. The Revolution is not beyond mercy.” She flipped to a page, held it up before her. “In exchange for information regarding the events of the week of Masens eleventh through twentieth, up to and including the massacre of the township of Stark’s Mutter, the destruction of the freehold of Lowstaff, and the disappearance of Revolutionary Low Sergeant Cavric Proud, I am willing to guarantee, on behalf of the Cadre, a swift and humane death.”

She set the paper aside, leaned forward. The woman stared just to the left of Tretta’s gaze.

“A lot of people are dead because of you,” Tretta said. “One of our soldiers is missing because of you. Before these six hours are up and you’re dead and buried, two things are going to happen: I’m going to find out precisely what happened and you’re going to decide whether you go by a single bullet or a hundred blades.” She laid her hands flat on the table. “What you say next will determine how much blood we see today. Think very carefully before you speak.”

At this, the woman finally looked into Tretta’s eyes. No fear there, she looked calm and placid as ever. And when she spoke, it was weakly.

“May I,” she said, “have a drink?”

Tretta blinked. “A drink.”

The woman smiled softly at her manacled hands. “It’s hot.”

Tretta narrowed her eyes but made a gesture all the same. One of her guards slipped out the door, returning a moment later with a jug and a glass. He filled it, slid it over to the prisoner. She took it up and sipped at it, smacked her lips, then looked down at the glass.

“The fuck is this?” she asked.

Tretta furrowed her brow. “Water. What else would it be?”

“I was figuring gin or something,” she said.

“You asked for water.”

“I asked for a drink,” the woman shot back. “With all the fuss you’re making about how you’re going to kill me, I thought you’d at least send me out with something decent. Don’t I get a final request?”

Tretta’s face screwed up in offense. “No.”

The woman made a pouting face. “I would in Cathama.”

“You’re not in Cathama,” Tretta snarled. “You’re not anywhere near the Imperium and the only imperialist scum within a thousand miles are all buried in graves beside the one I intend to put you in.”

“Yeah, you’ve been pretty clear on that,” the woman replied, making a flippant gesture. “Crimes against the Revolution and so on. Not that I’d ever call you a liar, madam, but are you sure you’ve got the right girl? There’s plenty of scum in the Scar who must have offended you worse than me.”

“I am certain.” Tretta seized the papers, flipped to a page toward the front. “Prisoner number fifteen-fifteen-five, alias”—she glared over the paper at the woman—“Sal the Cacophony.”

Sal’s lip curled into a crooked grin. She made as elegant a bow as one could when manacled and sitting in a chair.

“Madam.”

“Real identity unknown, place of birth unknown, hometown unknown,” Tretta continued, reading from the paper. “Professed occupation: bounty hunter.”

“I prefer ‘manhunter.’ Sounds more dramatic.”

“Convicted—recently—of murder in twelve townships, arson in three freeholds, unlawful possession of Revolutionary Relics, heresy against Haven, petty larceny—”

“There was nothing petty about that larceny.” She reached forward. “Let me see that sheet.”

“—blasphemy, illegal use of magic, kidnapping, extortion, and so on and so on and so on.” Tretta slammed the paper down against the table. “In short, everything I would expect from a common Vagrant. And like a common Vagrant, I expect not a damn soul in the Scar is going to shed a tear over what puts you in the ground. But what makes you different is that you’ve got the chance to do something vaguely good before you die, which is a sight more than what your fellow scum get before the birds pick their corpses clean.”

She clenched her jaw, spat her next words. “So, if you’ve got any decency left to your name, however fake it might be, you’ll tell me what happened. In Stark’s Mutter, in Lowstaff, and to my soldier, Cavric Proud.”

Sal pursed her lips, regarded Tretta through an ice-water stare. She stiffened in her chair and Tretta matched her pose. The two women stared each other down for a moment, as though either of them expected the other to tear out a blade and start swinging.

As it was, Tretta nearly did just that when Sal finally broke the silence.

“Have you seen many Vagrants dead, madam?” she asked, voice soft.

“Many,” Tretta replied, terse.

“When they died, what did they say?”

Tretta narrowed her eyes. “Cursing, mostly. Cursing the Imperium they served, cursing the luck that sent them to me, cursing me for sending them back to the hell that spawned them.”

“I guess no one ever knows what their last words will be.” Sal traced a finger across the scar over her eye, her eyes fixed on some distant spot beyond the walls of her cell. “But I know mine won’t be cursing.” She clicked her tongue. “I’ll tell you what you want to know, madam, about Lowstaff, about Cavric, everything. I’ll give you everything you want and you can put a bullet in my head or cut it off or have me torn apart by birds. I won’t protest. All I ask is one thing.”

Tretta tensed and reached for her saber as Sal leaned across the table. And a grin as long and sharp as a blade etched itself across her face.

“Remember my last words.”

Tretta didn’t achieve her rank by indulging prisoners, let alone ones as vile as a Vagrant. She achieved it through the support and respect of the men and women who saluted her every morning. And she didn’t get that by letting their fates go unknown.

And so, for the sake of them and the Revolution she served, she nodded. And the Vagrant leaned back in her chair and closed her eyes.

“It started,” she said softly, “with the last rain.”

You ever want to know what a man is made of, you do three things.

First, you see what he does when the weather turns nasty.

When it rains in Cathama, the pampered Imperials crowd beneath the awnings in their cafés and wait for their mages to change the skies. When it snows in Haven, they file right into church and thank their Lord for it. And when it gets hot in Weiless, as you know, they ascribe the sun to an Imperial plot and vow to redouble their Revolutionary efforts.

But in the Scar? When it pours rain and thunders so hard that you swim through the streets and can’t hear yourself drown? Well, they just pull their cloaks tighter and keep going.

And that’s just what I was doing that night when I got into this whole mess.

Rin’s Sump, as you can guess by the name, was the sort of town where rain didn’t bother people much. Even when lightning flashed so bright you’d swear it was day, life in the Scar was hard enough that a little apocalyptic weather wouldn’t hinder anyone. And as the streets turned to mud under their feet and the roofs shook beneath the weight of the downpour, the people of the township just tucked their chins into their coats, pulled their hats down low, and kept going about their business.

Just like I was doing. One more shapeless, sexless figure in the streets, hidden beneath a cloak and a scarf pulled around her head. No one raised a brow at my white hair, looked at me like they were guessing what I had under my cloak, or even so much as glanced at me. They had their own shit to deal with that night.

Which was fine by me. So did I. And the kind of shit I got into, I could always use a few less eyes on me.

Every other house in Rin’s Sump was dark as night, but the tavern—a dingy little two-story shack at the center of town—was lit up. Light shone bright enough to illuminate the dirt on the windows, the stripped paint on the front, and the ugly sign swinging on squeaky hinges: RALP’S LAST RESORT.

Apt name.

And it proved even more apt when I pushed the door open and took a glance inside.

Standing there, sopping wet, water dripping off me to form a small ocean around my boots, I imagined I looked a little like a dead cat hauled out of an outhouse. And I still looked a damn sight better than the inside of that bar.

A fine layer of dust tried nobly to obscure a much-less-fine layer of splinters over the ill-tended-to chairs and tables lining the common hall. A stage that probably once had hosted a variety of bad acts now stood dark; a single voccaphone stood in their place, playing a tune that was popular back when the guy who wrote it was still alive. Rooms upstairs had probably once held a few prostitutes, if there ever were prostitutes luckless enough to work a township like this. I’d have called the place a mausoleum if it weren’t for the people, but they looked like they might have found a crypt a little cozier.

There were a few kids—two boys, a girl—in the back, sipping on whatever bottle of swill they could afford and staring at the table. Laborers, I wagered—some young punks the locals used for cheap jobs with cheap pay to buy cheap liquor. And behind the bar was a large man in dirty clothes, idly rubbing the only clean glass in the place with a cloth.

He set that glass down as I approached. The cloth he had been polishing it with was likely used to polish something else, if the grime around the glass was any evidence.

No matter. I wouldn’t need to be here long.

Ralp—I assumed—didn’t bother asking me what I wanted. In the Scar, you’re lucky if they give you a choice of two drinks. And if you had any luck at all, you didn’t wind up in a place called Rin’s Sump.

He reached for a cask behind the bar but stopped as I cleared my throat and shot him a warning glare. With a nod, he held up a bottle of whiskey—Avonin & Sons, by the look of the black label—and looked at me for approval. I nodded, tossed a silver knuckle on the counter. He didn’t start pouring until he picked it up, made sure it was real, and pocketed it.

“Passing through?” he asked, with the kind of tone that suggested habit more than interest.

“Does anyone ever stay?” I asked back, taking a sip of bitter brown.

“Only if they make enough mistakes.” Ralp shot a pointed glance to the youths drinking in the corner. “Your first was stopping in here instead of moving on. Roads are going to be mud for days after this. No one’s getting out without a bird.”

“I’ve got a mount,” I said, grinning over my glass. “And here I thought you’d be happy for a little extra money.”

“Won’t turn down metal,” Ralp said. He eyed me over, raising a brow as it seemed to suddenly dawn on him that I was a woman under that wet, stinking cloak. “But if you really want to make me happy—”

“I’ll tell you what.” I held up a finger. “Finishing that thought might make you happy in the short term, but keeping it to yourself will make you not get punched in the mouth in the long term.” I smiled as sweetly as a woman with my kinds of scars could. “A simple pleasure, sir, but a lasting one.”

Ralp glanced me over again, rubbed his mouth thoughtfully, and bobbed his head. “Yeah, I’d say you’re right about that.”

“But I do have something just as good.” I tossed another three knuckles onto the bar. As he reached for them, I slammed something else in front of him. “That is, assuming you can make me happy.”

I unfolded the paper, slid it over. Scrawled in ink across its yellow surface was a leering mask of an opera actor upon a head full of wild hair, tastefully framed in a black box with a very large sum written beneath it and the words DEATH WARRANT above it.

“Son of a bitch!” Ralp’s eyebrows rose, along with his voice. “You’re looking for that son of a bitch?”

I held a finger to my lips, glanced out the corner of my eye. The youths hadn’t seemed to notice that particular outburst, their eyes still on their bottle.

“He has a name,” I said. “Daiga the Phantom. What do you know about him?”

When you’re in my line of work, you start to read faces pretty well. You can tell who the liars are just by looking at them. And I could tell by the wrinkles around Ralp’s eyes and mouth that he was used to smiling big and wide. Which meant he had to have told a few lies in his day, probably most of them to himself.

That didn’t make him good at it.

“Nothing,” he said. “I’ve heard the name, but nothing else.”

“Nothing else?”

“I know whatever they’re offering for his death can’t be worth what he can do.” Ralp looked at me pointedly.

I looked back. And I, just as pointedly, pulled my cloak aside to reveal the hilt of the sword at my hip.

“He has something I want,” I replied.

“Hope you find someone else who can find it.” He searched for something to busy his hands, eventually settling on one of the many dirty glasses and began to polish it. “I don’t know anything of mages, let alone Vagrants like that… man. They’re funny stories you tell around the bar. I haven’t had enough customers for that in a long time.” He sniffed. “Truth is, madam, I don’t know that I’d even notice if someone like that showed up around here.”

“Birdshit.” I leaned in even closer, hissing through my teeth, “I’ve been here three days and the most exciting thing I’ve seen was an old man accusing his wine bottle of lechery.”

“He has a condition—”

“And before I came in here, I glanced around back and saw your shipment.” I narrowed my eyes. “Lot of crates of wine for a man with no customers. Where are you sending them?”

Ralp stared at the bar. “I don’t know. But if you don’t get out, I’ll call the peacekeepers and—”

“Ralp,” I said, frowning. “I’m going to be sad if you make me hurt you over lies this pathetic.”

“I said I don’t know,” he muttered. “Someone else picks them up.”

“Who? What’s Daiga using them for?”

“I don’t know any of that, either. I try to know as little as fucking possible about that freak or any other freak like him.” All pretenses gone, there was real fear in his eyes. “I don’t make it my business to know anything about no mage, Vagrant or otherwise. It’s not healthy.”

“But you’ll take his metal all the same, I see.”

“I took your metal, too. The rest of the Scar might be flush with gold, but Rin’s Sump is dry as six-day-old birdshit. If a Vagrant gives me money for not asking questions, I’m all too fucking happy to do it.”

“Yeah?”

I pulled the other side of my cloak back, revealing another hilt of a very different weapon. Carved wood, black and shiny as sin, not so much as a splinter out of place. Brass glimmered like it just wanted me to take it out and show it off.

At my hip, I could feel the gun burning, begging to be unleashed.

“As it turns out, asking questions makes me unhappy, too, Ralp. What do you suppose we do about that?”

Sweat appeared on Ralp’s brow. He licked his lips, looked wild-eyed at my piece before he looked right back into the ugliest grin I could manage.

Don’t get me wrong, I didn’t feel particularly great about doing something as pedestrian as flashing a gun. It feels so terribly dramatic, and not in the good way. But you must believe me: I was expecting this to go smoothly. I hadn’t prepared anything cleverer at the time. And, if I’m honest, this particular gun makes one hell of a statement.

I certainly wasn’t going to feel bad about this.

Behind me, I could hear a hammer click. Cold metal pressed against the back of my neck.

“I got some ideas,” someone grunted.

Now this I might feel bad about.

Ralp backed away from the bar—though not before he scooped up the knuckles I left there, the shit—and scampered away to a back room. I let my hands lie flat on the table, my body still as a statue as I stood there.

“The Phantom doesn’t like people asking about him.” Male voice. Young. I could tell that even without him prodding me with the weapon like it was something else. “Thinks it’s terrible rude. I happen to agree with him.”

“As do I,” I replied, keeping my voice soft. “I must seem even more rude right now, keeping my back to you.” I spoke slowly, calmly. “I’m going to turn around and face you.”

“N-no!” His voice cracked a little. “Don’t do that.”

I was already doing it, though. I kept my eyes open, my lips pursed, my face the very picture of serenity as I pushed the scarf back over my head.

Not that I felt serene, mind you. My heart was hammering my ribs at that moment—you never get too used to having a gun jammed in your face, no matter how many times it happens. But it had happened enough times that I had learned a few things: I could tell a shaky hand by the feel of a barrel against my head; I could tell how far back a hammer was pulled by the sound.

And I knew that, if someone was intent on killing you, you damn well better make them look you in the eye while they do it.

When I turned around, I recognized the youth from the table—some soft-faced, wide-eyed punk with a mess of hair and a cluster of acne on his cheeks. He had a hand cannon leveled at my face. The other boy and the girl stood behind him, holding a pair of autobows and pretending to know how to use them.

Good weapons—too good for this hole masquerading as a township. It was unheard of to even see a weapon using severium this far away from a major city. But good weapons didn’t make good fighters. I saw their eyes darting nervously around, their hands quivering, too small to hold steel that heavy.

“You’re young,” I observed.

“Yeah? What of it?” the kid asked.

“Too soft to be working for a Vagrant,” I said. “Daiga must be desperate.”

“The Phantom’s not desperate!” He tried to sound convincing, but the crack in his voice was anything but. “He’s just on the run. He’s going to get out of this shithole soon enough and take us with him when he does.”

“Yeah,” the girl growled from behind him. “He’s going to show us magic, teach us how to be mages like him. We already hit an Imperial caravan with him! Scored a haul like—”

“I’m sure he was very impressed.” I kept my eyes locked firmly on those of the kid in front of me, pointedly looking past the barrel. “Why else would he have given you the very important task of picking up his wine?”

“Shut up!” the kid all but screeched. “Shut your fucking mouth! The Phantom—”

“Daiga,” I corrected.

“The Phantom said to kill anyone who came asking after him, any Imperial or… or… Revolutionary or…”

“Child,” I said. “I’m no Imperial, no Revolutionary. Daiga’s no hero who can get you out of here.” I stared into his eyes, forced myself not to blink. “And you’re no killer.”

His hands shook a little. Arm was getting tired. He held the hand cannon up higher to compensate.

“You’ve got a shit deal here,” I said. “I know. But pulling that trigger isn’t going to make it better.” I took a breath. “Put it down.”

Second thing you do to see what a man is made of, you put a weapon in his hands.

If he’s got any sense, he’ll put it right back down. If you’re fresh out of luck, he’ll hold it as tenderly as he would hold his wife. But as much as I don’t believe in luck, I believe in sensible people even less, so most of the time you get people like this kid: scared, powerless, thinking a piece of metal that makes loud noises will make anything different.

So when he realized it wouldn’t, when his arm dipped just a little, I knew I had this.

I grabbed him by the wrist, pushed the cannon away, and twisted his arm behind his back in one swift movement. He screamed as I pulled him close against me, circled my other arm around his neck, and looked over his shoulder at his friends. They hadn’t even raised their autobows before they realized what I had done.

“Listen up,” I snarled. “You want to put holes in your friend, you pull the triggers right now. You want everyone to come out of this alive, you put those things down and tell me where Daiga’s hiding out.”

I watched them intently, waiting for them to realize the shit they were in, waiting for them to drop their gazes, then their weapons.

Only, they didn’t.

They looked nervously at each other, saw the fear in each other’s eyes, fed off it. They raised their weapons, pointed them at me, fingers on the triggers. They took aim like they thought they wouldn’t hit their friend.

And that’s when I knew this whole thing had just gone to shit.

I shoved the kid out of the way just as I heard the air go alive with the screaming of autobows. Tiny motors whirred as they cried out, bolts flying from thrumming strings. Their shots went wide, missing both of us. I leapt behind the bar, ducked beneath it.

I heard wood splinter as they fired, bolt after bolt, into the wood, like they hoped the bar would just disintegrate if they poured enough metal into it. Sooner or later, they’d run out of ammunition, but I couldn’t wait for that.

Especially not once I heard the hand cannon go off.

A colossal flash of fire lit up the room. The ancient reek of severium smoke filled the air. And a gaping hole was now where half a bar had once been.

I pulled my scarf low against a shower of smoking splinters raining over me. He held a primate’s weapon—those things were just as likely to explode as fire—but it made a lot of noise and did a lot of damage, so I imagined he didn’t give a shit.

Besides, as I heard him reloading, I came to the same realization that he no doubt had.

He only needed to hit once. And I only had half a bar left to hide behind.

I pulled my gun free from its holster and it greeted me, all bright and shiny and eager to please. It burned warm, a seething joy coursing through my glove and into my palm. His bright brass barrel, carved like a dragon’s mouth, grinned at me as if to ask what fun thing we were about to do.

I hate to disappoint him.

Another hand went into the bag at my hip. The shells met my fingers. Across each of their cases, engraved in the silver, I could feel the writing. I ran my hands over each one, mouthing the letters as I did.

Hellfire—too deadly. Hoarfrost—too slow. Discordance—there’s my girl.

I pulled it out, flipped the gun’s chamber open, slid the Discordance shell in. I drew the hammer back, counted to three, then rose up behind the bar.

And, for the briefest of moments, I saw the look on the kid’s face. I’ve seen it a thousand times before and it never gets old. Eyes go wide, mouth goes slack as they stare down the barrel of my gun and, with numb lips, whisper the same word.

They knew his name.

I didn’t aim; with Discordance, you don’t have to. I pulled the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...