- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

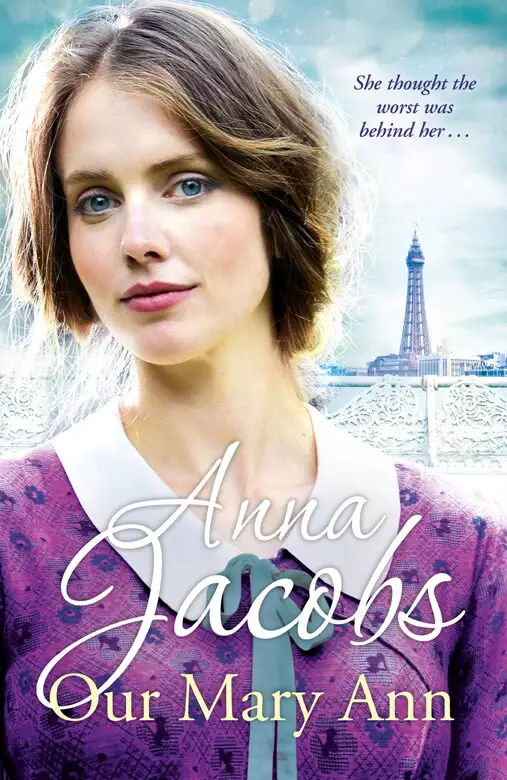

The final installment in the breathtaking Kershaw Sisters series.

She thought the worst was behind her....

Life is tough in Lancashire in 1905 — and especially so for 15-year-old Mary Ann, who was born out of wedlock. When her new stepfather begins to abuse her, Mary Ann doesn't know how much more she can take — until the worst happens and she is sent away to bear his child. After the birth, she manages to escape to Blackpool with the help of her new friend Gabriel.

Years later, the Great War brings Mary Ann many new opportunities, and brings Gabriel back into her life - but circumstances mean they can never be together. When her mother dies, Mary Ann decides it's finally time to return to Lancashire and uncover the secrets of her past. But an unknown danger threatens both her and the child she thought she'd lost forever....

Will history repeat itself — or will Mary Ann's courage win her the happiness she deserves?

Release date: October 9, 2010

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 300

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Our Mary Ann

Anna Jacobs

Taking up a position from which she could see out of the window but not be seen from the platform, she watched the crowd of passengers disperse. Only then did she leave the station.

As a child she’d played along all the back streets so knew exactly how to get to Stanley’s house without being seen. But even so her nerves were jittery as she hurried along the alleys between the terraces of narrow dwellings, holding her skirt up to keep it away from the gutter. Luck was with her. Apart from a group of small girls playing skipping games, she met no one.

‘Please let him be home,’ she muttered as she lifted the sneck on the back gate of the Kershaws’ home. She’d timed her arrival to coincide with Stanley’s return from work at two o’clock. The house was usually empty on a Saturday because his mother always visited her cousin and his father went to the nearest football match. She and Stanley had used that to their advantage many a time. Her lips curved into a half-smile as she remembered his big, strong body and dark curly hair. The only man she’d ever loved.

But today something was wrong. She could see through the window that the kitchen was full of people, and with a muffled squeak of dismay she took two hasty steps sideways to hide behind the shed. What was happening?

As the back door banged open and someone came striding down towards the privy, she slipped inside the shed, determined not to leave Overdale until she’d seen Stanley and sorted their problems out! She didn’t dare.

Through the tiny, smeary window she saw two men come out to stand on the back doorstep: his father and uncle, dressed in their Sunday best. Suddenly she heard them say something about ‘the bride’ and realised what was happening. A wedding. Who was getting married? And why was everyone gathering here? Stanley was an only child.

They went inside again and she saw people begin to leave the kitchen, heard the sound of their cheerful farewells fading towards the front of the house and the words ‘See you at the church’ repeated several times.

The back door opened and a man came out. She let out a low groan of relief. At last! As he passed by, she opened the shed door a few inches and hissed, ‘Stanley!’ He turned, looking puzzled, and she opened the door wide enough to show herself.

‘Dinah!’ He mouthed the word, staring at her in shock.

‘I need to see you,’ she whispered.

The back door of the house opened and someone called, ‘Hurry up, our Stanley! You don’t want to be late.’

‘You go ahead, Mam. I’ll catch up with you in a minute.’ He closed his eyes for a moment, then opened them to scowl at Dinah. ‘What the hell are you doing here? And today of all days.’

‘I need to see you.’

‘You said you never wanted to see me again! You said it very loudly. The whole street heard our final quarrel.’

Tears filled her eyes. She cried so easily now. ‘I never meant it. You knew I didn’t.’

‘I knew nothing of the sort,’ he said flatly. ‘You went away and returned my letter unopened. What else was I to think?’

‘Letter? What letter?’

He looked at her in puzzlement. ‘The one I sent the Wednesday after you left.’

‘I never even saw it.’ Dinah clapped one hand to her mouth. ‘Oh, no! My aunt must have sent it back. She was ill, frightened I’d leave her to cope on her own. She nearly died, so I couldn’t get away till now. When I didn’t hear from you, I wrote and asked my grandmother to tell you I was waiting for a letter.’

‘Well, she passed me in the street many a time, could easily have done that, but she never even tried to speak to me.’

Dinah put one hand to her mouth, feeling tears begin to trickle down her face. ‘Oh, Stanley, I didn’t know. They must have got together about this.’ Her aunt and grandmother were strict teetotallers and had never liked her going out with someone who worked in a brewery.

He sighed and looked at her less angrily. ‘Any road, it’s too late now. I’m getting wed today.’

The words echoed in her head and she couldn’t believe she’d heard them correctly, could only stare at him in horror. ‘You can’t be!’

He glanced over his shoulder, then back at her. ‘I’m sorry, Dinah. That’s how it is.’

She grabbed his sleeve to stop him moving away. ‘Who to?’

‘Meggie.’

‘That scrawny bitch! Stanley, no!’

‘She’s a nice lass and I love her.’ A fond expression settled on his face. ‘She’s got such dainty manners and ways – and she doesn’t throw temper tantrums like you.’

‘You said you were fond of me not so long ago.’

‘I was – once.’ He sighed and pulled his watch out, flipping open the cover and shaking his head at what he saw. ‘I have to go.’

‘You can’t!’ She took a deep breath and said it baldly. ‘Stanley, I’m expecting your child.’

He was so still she wasn’t sure he’d heard but as she opened her mouth to repeat the words he swallowed audibly, then whispered, ‘You can’t be!’

‘I can. It’s due in February.’

‘Oh, hell!’

‘So you’ll have to tell her you’ve changed your mind.’

He closed his eyes, then opened them again and looked at her with a pitying expression. ‘I can’t, Dinah. You see, she’s expecting my child, too. Only hers is due in March.’

One mew of pain escaped her, then anger began to scald through her. ‘You didn’t wait long, did you? You must have been with her almost as soon as I’d left.’

‘Aye. When my letter was returned I did it out of anger at first, heaven help me. But she did it out of love. And, Dinah – she’s a damn’ sight easier to get on with than you, and now … well, I love her. She depends on me and I’m not letting her down.’

Suddenly Dinah’s fury overflowed in a red tide, as it did sometimes, and she began beating at his chest, trying to scratch his face. They’d loved passionately, her and Stanley, but they’d fought fiercely too.

He held her off, then as she continued to struggle, gave her a hard shake. ‘Stop it!’

She fell against his chest, sobbing now, feeling helpless and afraid. ‘What am I going to do?’

His voice was grim. ‘Not cause trouble, I hope. Because it won’t do you any good. I shan’t change my mind. It’s Meggie I’m marrying.’

Dinah drew back, wiping her eyes with one arm, staring at him pleadingly and laying one hand on her stomach. ‘But this is your child as well.’

He nodded. ‘Aye, I believe you there. You’ve too hot a temper to lie and cheat.’ He felt in his pocket and pulled out his wallet. ‘I’ll give you some money. It’s all I can do now.’

‘Money!’ She spat the word at him. ‘What good is money? It’s a husband I need.’

‘Me and the lads went to the races last week and I had a bit of luck on the horses, couldn’t seem to go wrong. I haven’t told Meggie about it yet. Here, you can have half.’ He thrust some pound notes into her hand.

She nearly threw them back at him, only she couldn’t afford to do that. ‘A few miserable pounds!’ she whispered, looking down at them. ‘That’s not much of a heritage for your oldest child, is it?’

He shrugged. ‘I can’t marry two of you, can I?’

‘I’ll come to the church and stop the wedding.’

He looked at her pityingly. ‘You can’t stop it and you’ll only show yourself up if you try.’ He sighed. ‘Go back to your aunt’s, Dinah. Get her to help you, since she kept us apart. There’s nothing more I can do for you.’ He fumbled with his wallet, stuffing it anyhow into his pocket. ‘I really do have to go.’ He saw her open her mouth and added, ‘I want to go! You and I have nothing more to say to one another.’

Dinah bent her head and sobbed. When he made no effort to comfort her, she looked up to see the back door closing behind him. Disgust roiled in her stomach and she ran into the privy where she was violently sick. She came out, wiping her mouth, hating the sour taste, and decided she might as well go into the house and get a drink of water. There’d be no one there now.

She tripped over something on the mat and looked down to see Stanley’s wallet. It must have fallen out of his pocket in his haste. Picking it up, she opened it, staring in amazement when she found it still contained quite a bit of money. He must have had a really big win. Trust Stanley bloody Kershaw. He always had been lucky.

She put the wallet down on the table and got herself a drink of water, but as she was turning to leave, her eyes were drawn once more to it. He had given her only part of his money, the mean sod. She counted the rest of the notes out one by one, slapping them down on the table. Another twenty pounds. A fortune to someone like her!

Shoving the notes back into the wallet, she flung it back on the floor and turned to leave. But at the door she spun round and snatched it up again. Cramming it into her coat pocket, she hurried down the yard and slipped out of the back gate. Then she picked up her skirts and ran towards the station, terrified that he’d guess what she’d done and come after her, though she still retained enough sense to take the back alleys.

Just before she got there she stopped, shook out her skirt, adjusted her hat and blew her nose fiercely. She would get right out of his life, right away from Overdale too, and never come back, because she wasn’t going to face the shame of having folk point at her in the street for bearing an illegitimate baby. This child would be hers, all hers. As she settled herself in the train she glanced down at her stomach with its slight curve, thinking, Poor little thing! You’ll never even know your father.

Weary now, she sat staring out of the window as she began the first stage of the journey back to Blackpool, then leaned her head against the seat and closed her eyes. She’d have to plan this carefully. Her aunt wanted her to live with her permanently. If Dinah did that, she’d insist they move away from Lancashire and settle somewhere else – in the south perhaps. Too many people from Overdale came to Blackpool for their holidays, and anyway her aunt’s neighbours knew Dinah wasn’t married.

But if her aunt would sell the boarding house and move south, Dinah would be able to pretend she was a widow. And after what her aunt had done, keeping her and Stanley apart like that, just let her try to refuse!

Dinah’s expression grew softer as she thought of the baby. Mary Ann, she’d call it if it was a girl. That had always been her favourite name. She prayed desperately that it would be a girl. She wanted nothing more to do with men.

On her final day at school Mary Ann Baillie left home early, feeling near to tears. She loved school, had lots of friends there and was one of the top scholars. The only good thing about leaving was that she wouldn’t have to squash into a desk that was too small for her because at fourteen she was taller than any of the teachers and was already worrying about how tall she’d end up.

When she got to school, she waved and ran across the yard to where Sheila and the other older girls were sitting, plumping down beside them to a chorus of hellos.

‘I can’t believe we’ll not be coming here again,’ Sheila said with a sigh.

‘We can still see one another at weekends,’ Lucy said firmly. ‘We’ve all agreed that we’ll meet in the park on Saturday afternoons.’

Mary Ann bent her head to hide sudden tears, but of course they noticed.

‘What’s wrong?’ Sheila asked.

‘When I told my mother about that, she said she’s not having me messing about in the park, getting into trouble.’ She blinked furiously as tears threatened. ‘I don’t get into trouble. Why does she always say that?’

There was silence. Everyone knew how strict Mary Ann’s mother was.

‘Perhaps now you’re nearly grown up it’ll be different?’ Sheila ventured.

Mary Ann shook her head, not saying anything because if she did she’d cry again. She’d cried herself to sleep last night when her mother had told her that she wouldn’t be allowed out on Saturdays.

‘Well, think how lovely it’ll be to earn money at last,’ Lucy said. ‘I can’t wait for my first wage packet. My mother says I can have that one all for myself – though I have to give her some from then onwards.’ She turned to Mary Ann. ‘Are you still going to work for your mother?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is she going to pay you?’

‘Not proper wages, just spending money.’ It wasn’t fair. Their boarding house was comfortable and nearly always full. One day, when she was dusting, Mary Ann had found her mother’s savings book with over three hundred pounds in it, an enormous sum of money. She hadn’t said anything because Mum would only have flown into a temper, but she’d never forgotten it, especially when her mother later told her they couldn’t afford the material for a new Sunday dress and Mary Ann would have to put a false hem on her old one.

The final day flew past far too quickly. Mary Ann won a prize for being the most capable senior girl, which had her blushing and beaming at her clapping friends as she went to receive it from the Headmaster. Sheila won the needlework prize and Lucy the arithmetic prize. All the prizes were the same: books. Mary Ann’s was God’s Good Man by Marie Corelli, which thrilled her. She loved to read stories, but her mother hated to see anyone being idle so she could only usually read at school.

When the final bell clanged, the girls were slow to leave the yard, parting from one another only after tearful promises to stay in touch.

At home Mary Ann found her mother starting to prepare the boarders’ evening meal.

‘You’re late.’

‘It was the last day. I was saying goodbye to everyone. Look!’ She held out the book. ‘I won a prize for being the most capable girl. It’s by Marie Corelli.’

Her mother sniffed. ‘You’d think they’d buy you something better than that rubbish.’

‘It’s not rubbish! Miss Corelli writes lovely stories and there are hundreds of books by her in the shops. All the girls read them and lots of their mothers do, too.’

‘Well, I’ve better things to do with my time and you’ll not be reading it till your work is done.’ Dinah looked at the clock and clicked her tongue in exasperation. ‘We’re getting a new lodger from Henderson’s, so we’re going to be full up again. I knew they’d soon find another rep to replace poor Mr Brown. Powling, this one’s called.’

Mary Ann automatically began to clear things off the kitchen table, piling up the dirty dishes in the scullery, ready to wash. ‘Can I let my skirts down now I’ve left school?’

‘At fourteen? Certainly not! You’re still a child. Now stop asking silly questions and put that satchel away in the attic. You can take the book up to your bedroom while you’re at it.’

‘I wanted to show it to Miss Battley.’

‘She won’t be interested in that. Hurry up, now. I need you to peel the potatoes.’

While Mary Ann was upstairs there was a knock on the door and with a mutter of annoyance Dinah wiped her hands and went to open it. A man was standing there, smiling. She gasped in shock and could not for a moment move, thinking it was Stanley Kershaw. He was tall and well-built with dark wavy hair, but even though she’d quickly realised it wasn’t Stanley, she still felt shocked by the man’s superficial resemblance to her former lover.

He cleared his throat. ‘Are you all right?’

She pulled herself together. ‘Yes. Yes, of course. It’s just – you look like someone I used to know and I was shocked.’

‘It happens sometimes, doesn’t it? I’m Jeff Powling, the new sales rep for Henderson’s. They said they’d booked me a room here.’

For a moment she had the strangest premonition that this man was dangerous and felt an urge to slam the door in his face. Then she brushed the silly fancy aside and held the door open wide. ‘Do come in, Mr Powling. We were expecting you.’ She led the way up the stairs at a brisk pace.

He looked round the bedroom and nodded approval. ‘I must say, you’ve got everything very nice, Mrs Baillie, much nicer than my last place.’

‘Thank you. The evening meal is at seven o’clock sharp.’ She smiled and left him to unpack, but the smile faded as she walked slowly down the stairs. She didn’t want to be reminded of Stanley, had tried for years to forget him.

She hadn’t managed to do it, though, because her daughter looked so much like her father, with the same wavy hair, grey eyes and broad smile.

Mary Ann met the new lodger when she helped serve the evening meal, but as she’d never seen a photograph of her real father she didn’t notice anything special about him. Mr Powling had already made himself known to the others and was chatting to Miss Battley who had been lodging with them for several years and whose gruff exterior hid a kind heart, as the girl had found.

Mr Powling was quite good-looking, considering he was about her mother’s age, though the smile didn’t reach his eyes, especially when he was talking to Mary Ann. But he was all over her mother and the other female lodgers, the girl noticed.

And, for once, her mother was smiling and blushing as they chatted – something she had never done before with a lodger.

‘Mum, why do you talk to him like that?’ Mary Ann asked a few evenings later.

‘Talk to who?’

‘Mr Powling. Why do you smile at him and stand talking to him for so long? I don’t even like him.’

Her mother drew herself up and frowned. ‘It’s part of our job to make sure our guests are happy. If they’re not happy, they won’t stay.’

‘But you don’t talk to the other men like that.’

‘Just who do you think you are, young lady, commenting on your elders? What I do is my own business. Now go and make those beds.’

The next night her mother was smiling again and as soon as they’d served tea, she said, ‘You’ll have to clear up the rest tonight. Mr Powling has invited me to go with him to the music hall. I haven’t been out for ages and there’s a really good show on this week, apparently.’

Before Mary Ann could say a word, her mother had gone running upstairs to change, coming down again a few minutes later wearing her new Sunday outfit, an ankle-length gored skirt and a three-quarter jacket to match. On her head was a matching toque with a feather curling backwards across it.

There had been enough money for her mother’s new clothes, Mary Ann thought resentfully. Scowling, she cleared up, set out the tea tray and biscuits for supper, then sat down by the kitchen fire, feeling too exhausted to go and fetch her new book. She’d never worked as hard in her life, because her mother had dismissed their maid of all work and now they managed with just the two of them and a scrubbing woman.

She stabbed the poker into the coal to get a better blaze. It was all very well her mother having a night out, but Mary Ann hadn’t been able to meet her friends once since she’d left school. She wasn’t allowed to go out in the evenings because her mother said she wasn’t having her daughter hanging around on street corners after dark getting into trouble. Why did she always worry about that? What sort of trouble could anyone get into talking to their friends? Sheila was allowed to come to the house in the evening – only she hadn’t done that after the first visit, because Mum hadn’t left them alone and they hadn’t been able to talk properly.

After the lodgers had had supper, Mary Ann cleared up again, washed the dishes and filled herself an earthenware hot water bottle, more for the comfort than because it was cold yet. Her room was in the back attic, away from the rest of the house, which she normally loved because it was quieter up there. But tonight she left the door open because she couldn’t get to sleep until she knew her mother was safely back.

Only Mum and Mr Powling didn’t return until nearly eleven o’clock.

In the morning her mother hummed as she got the breakfasts and Mary Ann noticed Mr Powling got the best of everything on his plate. She didn’t say anything, though. Mum had a nasty temper if you crossed her and could slap you really hard if you upset her.

The things her mother said sometimes when she was angry could hurt even more than the slaps.

By the following week Mary Ann was so fed up of doing nothing but work, work, work that she decided to make a stand. ‘I’m going out tomorrow afternoon to see Sheila and the others,’ she declared on the Friday, chin up.

‘I’ve told you before, I won’t have you hanging round street corners,’ her mother said automatically.

‘We’re meeting in the park. I haven’t been out once since I left school and I’m fed up of staying in.’ She loved going to the beach or walking past the old Royal Pavilion with its strange roof. She liked going on the Palace Pier and looking down at the water.

‘You go out every day to the shops for me.’

‘That’s not the same. And I think I deserve more than a shilling a week spending money, too. I work hard and––’

Her mother’s heavy hand cracked across her cheek.

‘Ow!’ Mary Ann began to sob loudly.

‘Be quiet! The lodgers will hear you.’

‘I don’t care.’ She dodged round the table, avoiding another smack. ‘I’m not working here if I don’t get paid and I can’t ever go out.’

‘Oh, aren’t you? And what do you think you’ll do instead?’

‘Go into service. Gertie says her mistress wants another maid.’ She shrieked and ran as her mother’s face turned dark red and she raised her hand again. But as the girl tried to get out of the kitchen, she banged into someone and couldn’t get past. ‘Let me go!’

‘Hold still, young woman. What’s all this about?’

Mary Ann suddenly realised it was Mr Powling. He was holding her pressed right against him and though she tried to wriggle away, he was stronger than she was and wouldn’t let her go.

He looked sideways at her mother. ‘Having a bit of a tiff ? Want me to leave?’

‘Madam here is demanding to go out with her friends and she wants more money. I’m not having it.’

‘Oh, is that all?’

At last he let her go and in her relief Mary Ann moved hurriedly back to her mother’s side, only to get another crack on the cheek. She wasn’t going to cry in front of him, but she thought it mean of her mother to treat her like that in front of a lodger and looked at her reproachfully. For a moment she thought she saw an expression of shame, then her mother tossed her head and turned back to Mr Powling.

‘What can I do for you, Jeff ?’

Mary Ann stilled. Her mother never called guests by their first names.

‘I was wondering if you were going to be busy tonight, Dinah? Only there’s another good show on and it’s much more fun to go with someone.’

‘Oh.’ Her mother turned sideways to look at Mary Ann. ‘You can manage the suppers, can’t you?’

‘If I can go out tomorrow.’

Her mother’s expression grew angry again, but Mr Powling laughed. ‘You’re over-protective of her, Dinah. What harm can she come to on a Saturday afternoon?’

Mary Ann could have sworn there were tears in her mother’s eyes and it was a minute before she spoke.

‘Oh, very well. But only for a couple of hours, mind. Now, go and set the tables for breakfast and I want no more cheek from you, young lady.’

Mary Ann began to do the tables. A couple of times she had to go into the kitchen for something and the two of them were still there, sitting close together at the end of the table, talking in low voices, laughing sometimes. They fell silent each time she went in and didn’t start talking again until she’d left and she couldn’t help wondering what they were laughing about.

Well, at least she’d be able to see her friends again. But she hadn’t liked it when Mr Powling caught hold of her. It wasn’t nice to press against someone like that.

Gabriel Clough sat up on the moors looking down towards Overdale. He sighed and reached out to pat his dog, Bonnie. When she leaned against him, he continued absent-mindedly to caress her.

Below him was the familiar patchwork pattern of fields edged in dry stone walls. Around him the green curves of what locals referred to as ‘the tops’ stretched right to the horizon, a place belonging to no one, without roads or walls to bar the way. If you half-closed your eyes, it looked a bit like the sea – or as he imagined the sea would look. He’d never seen it except in pictures, never done anything much, really. Just gone to school when he had to, working on the farm before and after school, so that he was always too tired to pay much attention to his homework.

He’d left at fourteen and had been planning to leave Birtley, his home village, as soon as he was eighteen, wanting to see a bit of the world before he settled down. But just before his birthday, two years ago, his father had had a stroke, so now his parents couldn’t manage without him. Farms like theirs didn’t bring you a generous living at the best of times and when one of the two men was half-crippled, it was even harder to make ends meet.

Gabriel’s whole life now seemed made up of nothing but work and then more work, but he could see no way out. It was a lonely life, too, he and his dog working with the sheep or tending the small crops they grew mostly to feed themselves and the stock.

Birtley was a mere hamlet, only a dozen houses, and there was no one his own age left there now because they’d all gone to work in the towns. If only his elder brother had lived, Gabriel would be working in a town now, too! But Paul had died aged eight and now there was just him, a late child born to elderly parents.

Lower down the valley was Redvale, an old farmhouse bigger than the others hereabouts, built of brick not stone, and with more land. Nowadays its owner was just as short of money as everyone else, however. Maurice Greeson had inherited it a year ago from his father and everyone was watching to see what changes he’d make and whether he’d nudge the farm into profit. They weren’t optimistic. Neither he nor his father had ever been noted for their energy or acumen.

The first change had been for him to get married to the woman he’d been walking out with for years, a woman slightly older than himself and cleverer, too. Well, everyone said she was clever. Jane Greeson had been a nurse until she married, but Gabriel couldn’t see her bringing much comfort to sick people. She had a cruel face and he pitied the poor little skivvy who worked for them and always looked exhausted.

Devious might be a better word to describe their neighbour. Gabriel rolled the word round his tongue, enjoying it. He’d been good at reading and writing at school, and had always enjoyed finding exactly the right word to describe something. His father mocked him for using long words, but Gabriel didn’t see what was wrong with that.

Suddenly he noticed that some stones had come loose in the top corner and heaved himself to his feet. The whole damned wall round this top field needed rebuilding, really, but let alone he wasn’t an expert on dry stone walls, he didn’t have the time to do it. Picking up the stones, he fitted them carefully into the gaps, surprised to find there weren’t nearly enough of them. Had someone been up here stealing them? That had happened to a few folk lately.

He clambered across the wall and found footprints in the soft earth, following them down to the Greesons’. He even saw the stones, standing in a pile in a corner of their yard.

Anger rising in him, he banged on the back door, turning sharply when a dog growled behind him. ‘Don’t you dare!’ he told it, and after hesitating for a moment, it slunk off.

‘What do you want?’ Maurice offered by way of a greeting.

Gabriel jerked his head towards the pile of stones. ‘My property back.’

‘I thought your dad was letting that top field go.’

‘Well, he isn’t letting the wall go, or giving the stones away. I need them to repair it.’

‘Sorry. I’ll return them later today.’

‘Thanks.’ Gabriel turned and walked away. On the face of it, the right response, just what you’d expect from a neighbour, but all done in a surly, grudging way. You had to keep your eye on the Greesons.

When Gabriel got home, his mother was looking worried and his father was slumped at the kitchen table, his face grey with exhaustion.

Jassy greeted her son with, ‘Your father’s been doing too much again.’

He looked at the old man. ‘What was so urgent it couldn’t wait for me to get back, Dad?’

‘There’s a dozen jobs waiting here while you’re fiddling about in the top fields staring out across the moors.’

‘I wasn’t fiddling around. I was rebuilding the wall. That end bit had fallen down again. Then I had to go to Greesons’ to get the rest of our stones back because Maurice had taken them.’

That jerked his father out of his misery. ‘He’s a menace, that fellow is, always taking things that don’t belong to him. I don’t know what the world’s coming to when neighbour steals from neighbour like that.’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...