It looked all wrong.

DI Rachel Prince fixed her gaze on the file that lay open on her tray table, staring at the photos of the perfect, broken body. She went over the accompanying statements not once but twice – then three times – re-reading the same paragraph several times in an attempt to make sense of it.

She had been trying to get up to speed on the case for the past twenty minutes, since the plane had taxied along the runway bound for Edinburgh. The prospect of a hot train in the height of the summer holidays had not appealed, so she was flying there instead. Okay, so the plane was also full, but at least the journey was only a bearable fifty-five minutes. It would be okay.

But this – the story outlined in her briefing note about a beautiful young woman randomly falling to her death – this was not okay. The component parts of the account did not add up. The case had been sold to her as something of a diplomatic mission, but this didn’t look like a mere box-ticking exercise. Far from it.

Twenty-four hours earlier she had received an early morning phone call from Commander Nigel Patten, her boss at the National Crime Agency, asking her not to go into the office in South London, but instead to meet him in leafy, upmarket Kensington. This was an unusual request, to say the least, but she had driven straight to 35 Hyde Park Gate.

Leaving the force field of her car’s air-conditioning, Rachel had immediately been too warm in her informal work uniform of black trousers and long-sleeved white shirt. An August heatwave was suffocating London, and although it had only been 8.30 a.m., it was already well over twenty degrees centigrade. She had rolled up her sleeves as far as they would go, wishing she’d worn sandals instead of trainers. By the afternoon it would not only be hot, but uncomfortably humid too.

The building she had been summoned to turned out to be the Embassy of the Netherlands, occupying the whole of a red-brick mansion block. A red, white and blue flag and the insignia of the European Union flew above the front entrance. This was certainly not a normal work venue, Rachel had thought, but then arriving at a job without a clue what was involved was hardly normal either.

Patten had intercepted her as soon as she came into the foyer. He had seemed jumpy, uncomfortable. He was in his late forties, losing his hair and looking a little weathered, but slim and fit for his age. He needed to be: he had recently remarried and started a new family with a much younger second wife.

‘There’s no time to brief you, I’m afraid, so you’ll just have to listen in for now, and we can talk properly afterwards.’ He had looked Rachel up and down, taking in her bare forearms. ‘And you might want to roll your sleeves down.’

She had duly adjusted her shirt, and he had led her into a high-ceilinged, thickly carpeted room, where several people were seated around a large oval table. Without exception their expressions were grave, strained.

A tall, distinguished man with greying hair stood up and extended a hand.

‘This is His Excellency Mr Carolus Visser, the Dutch Ambassador.’ Patten had made an obsequious movement that was not quite a bow as he said it. ‘Your Excellency, this is my colleague Detective Inspector Rachel Prince. She’s one of our international liaison officers here in London.’

Rachel shook the man’s hand and sat down next to Patten.

‘Detective Prince; we’ve arranged this meeting on behalf of one of our nationals, Dries van Meijer.’ The ambassador, whose English was fluent and barely accented, had indicated the man sitting on his left. He was younger, equally tall, with square horn-rimmed glasses and dark blonde hair slicked back in the manner favoured by City financiers. His pale-grey suit, Rachel had assessed with a practiced eye, was custom-tailored and expensive, as were the cutaway-collared shirt and the diamond-studded cufflinks. The stark black silk tie had made a discordant note in his urbane appearance.

‘I’m afraid we’re here under what are the most unfortunate – tragic – of circumstances. Mr van Meijer’s daughter was visiting the Fringe Festival in Edinburgh last week when she sadly passed away.’

Rachel had looked again at van Meijer, and took in the pink-rimmed eyes behind the glasses, the unhealthy tinge to his tanned skin. He looked down at his hands, twisting a gold signet ring.

‘The Procurator Fiscal in Edinburgh has concluded that my daughter’s death was an accident,’ he said. His voice was strained, tinged with anger. ‘They said there was no need for a formal enquiry. The police are unwilling to take the matter further, but I – we – find this totally unacceptable.’

‘Mr van Meijer asked us to approach Interpol on his behalf, and I explained that in this country, Interpol is now part of the National Crime Agency,’ Visser had continued, pausing briefly to rest a hand on top of van Meijer’s. ‘My contacts at the Foreign Office put me in touch with Commander Patten.’

Patten had given a brief nod of acknowledgment. ‘And I’ve offered our assistance in establishing the facts, as far as we are able.’ He looked round the table. ‘DI Prince is one of our most experienced investigative officers, and we would be very happy for her to go to Edinburgh on Mr van Meijer’s behalf and find out as much as possible about the circumstances surrounding the death of his daughter.’

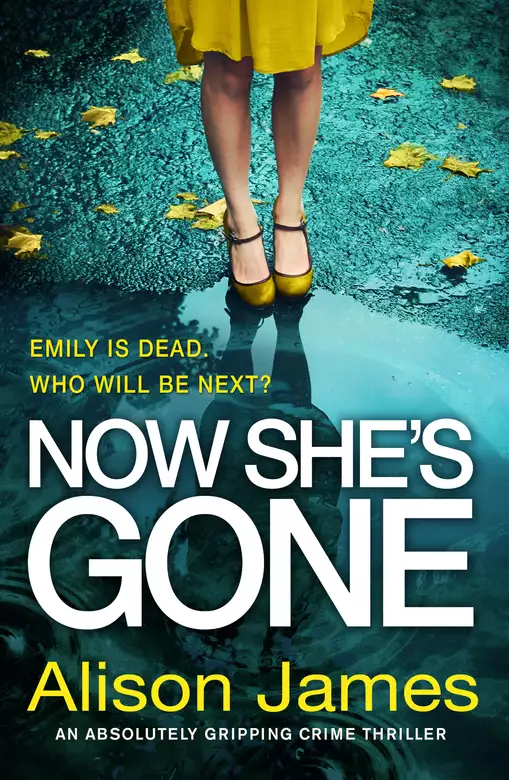

‘Emily,’ van Meijer had said bleakly. ‘Her name is Emily.’

‘It’s a tricky one,’ Patten had offered as they left the building together. ‘Not to mention a bit of a political hot potato.’

‘Yes, I can see that.’ Rachel’s tone had been dry. ‘Otherwise why would we be acting as private investigators on behalf of a foreign national?’

They had reached Patten’s car at this point: his driver waiting patiently with the engine running to keep the air-conditioning circulating. The sun was climbing behind a thin veil of heat haze, and Rachel could feel her armpits growing damp.

‘Can I give you a lift?’ Patten had asked,

She shook her head. ‘I drove here.’

‘Okay, well… it’s too hot to stand around on the street and talk.’ Patten said, ducking his head to climb into the back seat. ‘I’ll see you back at the office and we can go into it all properly then.’

Rachel had arrived at the office to find that her Detective Sergeant, Mark Brickall, had rigged up a desk fan that blew air directly into his face, and was sucking ostentatiously on a strawberry ice lolly. The NCA building in Tinworth Street was supposed to be air-cooled, but the ventilation system was outdated and only circulated stale, lukewarm air.

‘Bit early for sweet treats, isn’t it?’ Rachel had indicated the lolly. ‘Even for you. It’s not eleven o’clock.’

‘Temperature’s going to get up to thirty-five centigrade today, loser.’ Brickall had wiped his mouth with a paper towel and tossed it into his waste bin. ‘I’m just making like a boy scout and being prepared.’

‘In that case,’ Rachel had stood up again and adjusted the fan so that it blew air over her desk too, ‘how about you behave like a proper boy scout and do a good turn.’

Brickall had put out a hand to move the fan back again, but having caught sight of her expression changed his mind, taking a file from the heap on his desk and studying the contents earnestly. This was New Improved Brickall. He had recently been reinstated following a six-month suspension for professional misconduct. Since his return he had been making a show of working hard and playing strictly by the rules; with every piece of paperwork checked and double-checked to make sure it was absolutely correct. It was out of character – Old Brickall was slapdash about paperwork and had little time for protocol.

‘Where have you been, anyway?’ he had enquired. ‘I asked Margaret but she denied all knowledge of a meeting. Not that I expected her to know.’ He had made this jibe warmly: their clerical assistant Margaret was popular, if not a titan of efficiency.

‘Something Patten sprung on me out of the blue,’ she told Brickall. ‘I need to go and have a debrief with him now, in fact.’ She picked up her notebook and a pen. ‘Tell you about it later. Mine’s an orange Solero, by the way, on your next ice-cream run.’

‘Dries van Meijer is not just any foreign national,’ Patten had spoken heavily as Rachel sat down on the chair that faced his desk. ‘He owns one of the world’s biggest marine engineering companies, so he’s hugely powerful. That’s why we find ourselves in this situation.’

Rachel nodded. ‘Ah. I see.’

‘If van Meijer tells him to jump, the Dutch ambassador has no choice but to ask “How high?” He can’t just fob him off: it’s out of the question.’

‘So what happened to his daughter?’

‘I only have the few details I was given before you arrived this morning. The girl was on a cultural trip to the Edinburgh festival, along with a group of other teenagers, all from European countries. She seems to have gone out walking late at night after drinking and suffered some kind of fall. The Dutch ambassador promised to send over a more detailed briefing note later today, so I don’t know the full story. Not yet. Anyway… the Procurator Fiscal has the option to order a Fatal Accident Inquiry in the event of an unexpected death, at his discretion. Following enquiries by Edinburgh police, he declined to do so. As you probably know, in Scotland they don’t have coroners or inquests like we do south of the border. The system is quite different to ours, where an inquest would have been inevitable.’

‘But if I go up there asking questions, implying the local police have fallen short… well, as you said yourself sir, it’s politically extremely awkward.’

Rachel had been referring to the fact that the National Crime Agency had limited jurisdiction in Scotland. Operating there at all was conditional on authorisation from the Lord Advocate and could only be done with approval from Police Scotland.

‘You’re absolutely right, DI Prince.’ Patten had poured himself a glass of water from the jug on his desk and taken a sip. He offered the jug to Rachel, but she shook her head. ‘It is awkward. It’s going to require very careful handling indeed, but I have full trust in your abilities. And in reality it boils down to a box-ticking exercise; you just need to go up there and confirm that it was indeed a tragic accident. That way we’ve done our bit and the Dutch will be satisfied that their concerns have been heard.’

Even then, Rachel had been doubtful that reality would align with Patten’s glib summary, but had not said so. ‘I take it I need to go straight away, sir?’

Patten had nodded, dabbing the sweat from his forehead with his pocket square. ‘Janette will help sort arrangements. Look on the bright side: at least it will be cooler north of the border.’

As she had stood up to go, he added, ‘And take DS Brickall with you. You’re perfectly capable of handling this alone, but after his recent… history… I want him where you can keep an eye on him.’

By the time her flight landed at Edinburgh Airport, Rachel had read the brief file from cover to cover several times, and knew the contents off by heart. The many gaps in the information had thrown up even more questions. But that was what she was here for: to find answers.

Emily van Meijer, aged seventeen, had been attending the festival as part of a group organised by a travel company called White Crystal Tours. They brought teenagers from all over Europe on cultural trips to Edinburgh. Accommodation and half-board was provided, and they were chaperoned to appropriate cultural events. Alcohol consumption was strictly against company policy, but on the evening of Monday 7 August a half-empty bottle of Southern Comfort was found in Emily’s room. The girl was missing, having apparently said earlier in the day that she wanted to climb Arthur’s Seat to take photos. After several hours, when she failed to return, the tour organisers alerted the local St John mountain rescue team, who found the girl’s body at the foot of a sheer rock face at Salisbury Crags. Police Scotland were called, but after examination of the scene and a routine post-mortem, decided against initiating further enquiries.

Case closed.

Except that the van Meijers were unwilling to accept this conclusion, insisting that their daughter didn’t drink, wasn’t particularly interested in photography and was not the sort of girl who bent the rules. In short, she wouldn’t have behaved in this way. But all parents would say that about their child’s accidental death, thought Rachel. Wouldn’t they?

Finding accommodation in Edinburgh during the festival was notoriously tricky and expensive, not least at twenty-four hours’ notice. The city centre itself lacked even a bed in a shared hostel room, but nothing was beyond Janette’s organisational powers. At the NCA they joked that Janette could airdrop you into a warzone and still secure you three-star accommodation. She had managed to source an empty room in the Avalon Guest House in Coates, less than two miles to the west of the city centre, and Rachel took a cab straight there from the airport. The decor in the public areas was fussy and overly grand, and the room was tiny, but she was grateful to have somewhere central to make her base. As soon as she had unpacked, she texted Brickall, who had elected to travel on the train, claiming it would be easier than flying.

Just arrived. ETA?

He replied a few seconds later.

We’re on the train. Due in to Waverley at 14.17.

Rachel drew back from her phone screen, startled.

We??

Me and the female in my life.

No idea what you’re talking about, but will meet you at Waverley anyway.

Rachel recognised the confident, swaggering walk straight away, even though Brickall was not tall enough to stand out in the crowd of disembarking passengers. He was alone.

Or not exactly alone. There was no human female companion with him, but trotting along beside him on a red lead was a small sandy-coloured dog. She had a silky coat, soulful eyes and a melancholic expression.

‘This is Dolly,’ Brickall introduced her.

‘You’ve got a bloody dog?’

‘Not exactly. She belongs to a mate of mine, only he’s emigrated to New Zealand. So I said I’d mind her until he could make a more permanent arrangement for her.’ He reached down and fondled one of her floppy ears. ‘She’s a good girl, aren’t you Doll? She won’t be a problem.’

Rachel doubted this. ‘So that’s why you wanted to take the train up here?’

‘Exactly, Sherlock.’

‘Okay, well… I was going to suggest we visit the scene, but I suppose the dog can come with us. We’ll need to drop your stuff first. Where are you staying?’

‘In the arse end of beyond. It was tricky finding a place where I could bring Dolly. But we can get the tram most of the way, I think.’

They emerged up the station steps to a slow-moving swell of people. Festival madness was peaking, and the pavement was thick with dawdling tourists, buskers and jugglers. Every few steps they took, someone approached them and thrust a flyer into their hand, inviting them to attend a satirical review, stand-up comedy, a poetry reading, a conceptual art show.

Dolly quivered and tried to melt into Brickall’s ankles. He handed Rachel his backpack and picked up the dog to carry her. Eventually they fought their way along Princes Street to the tram stop. As Patten had predicted, the temperature was almost fifteen degrees lower than in London, with a pale blue sky only just visible behind voluminous grey-white clouds.

They left the tram at Balgreen and walked for fifteen minutes to the outskirts of Corstorphine, with Brickall using Google Maps on his phone to navigate. His digs were in a pin-neat, one-storey villa, where the landlady, Mrs Kilpatrick (‘Call me Betty’) immediately gushed and fussed over Dolly as if she’d acquired a new grandchild.

‘Oh, the wee dote! Look at her: she’s gorgeous. What sort of dog is she?’

‘An American Cocker Spaniel,’ said Brickall, like a proud parent. Dolly stared at the middle distance with a worried expression as she was stroked.

‘She’ll be hungry perhaps?’ said Betty. ‘Or thirsty after the journey.’ She fetched two bowls, one filled with water and one with kibble. Dolly lapped at the water noisily then ate a single biscuit, as though determined to be polite.

‘The wee darling! Now, can I get you and your girlfriend some tea? And maybe some fruit cake?’

‘She’s not my girlfriend.’

‘I’m not his girlfriend.’

They spoke in perfect unison.

Brickall reluctantly declined – or at least deferred – the tea and cake, explaining they were there to work, and planned to start immediately. He also declined Betty’s offer to mind Dolly, on the grounds that she had been on a train for over four hours and needed a good walk. He and Rachel, along with the dog, set off back to the tram station, taking it to the eastern end of the line, walking another mile through the unrelenting crowds to Holyrood Park, and then hiking up the looming, volcanic Salisbury Crags. The scrubby grassland gave way abruptly to a sheer, 150-foot rocky drop.

‘Amazing view,’ observed Brickall, reaching down to pat Dolly, who had flopped down, exhausted, at his feet. As he spoke, the clouds thinned and parted and they were treated to a spectacular view over the city. It was even cooler than street level, and breezy.

‘I think I prefer it up here,’ said Rachel. ‘All those people do my head in. I don’t know how people who live here cope with it every summer.’

‘Money,’ said Brickall bluntly. ‘It brings in hundreds of millions to the city every year. They kind of have to put up with it.’

He handed Dolly’s lead to Rachel and walked right up to the edge of the crag.

‘Careful,’ Rachel said instinctively. The dog pinned back her ears and whimpered.

Brickall peered over the edge, being careful to plant his feet and keep his body weight tipped back.

‘You could see how it could happen,’ he said as he walked back to Rachel. ‘It’s dark, you lose your footing…’

‘But if it was dark, why would Emily have wanted to take photos?’ Rachel asked. ‘It makes no sense.’

‘Unless you’re a pissed teenager. Then any crazy shit makes sense. I did a bit of research of my own on the way up here: people fall off here and Arthur’s Seat,’ he pointed to the dormant volcano looming above them, ‘all the time. Multiple fatalities every year. Especially at night, when tourists come up here to admire the city lights. The local plod were spot on: it was just an all-too-predictable accident.’

‘Looks that way,’ Rachel agreed. ‘But to complete Patten’s diplomatic mission, we still need to go and speak to Police Scotland. And maybe make a few enquiries of our own into what happened that night.’

Gusts of wind swirled around them, and Dolly quivered.

‘Like I said; just a kid who couldn’t hold her drink and paid the price.’ Brickall turned back down the path. ‘Come on. Doll here has had enough, and there’s a piece of fruitcake with my name on it back at Betty’s.’

They beat a path back through the city centre, past queues of event attendees that seemed to spill out of every building, blocking the pavements.

Once they reached the western edge of the city, Rachel and Brickall parted company, and she returned to her guest house and took a long hot shower. There was no such refinement as a minibar, but a pleading phone call to the front desk resulted in a waitress bringing a vodka and tonic to her room. She sat on the edge of her bed, sipping the icy and pleasantly bitter liquid and staring at her phone.

Her ex-husband Stuart Ritchie lived in Edinburgh, and they were now on friendly terms after a long estrangement. Much as Rachel was glad that she and Stuart were speaking again, there was something faintly awkward about landing an investigation on his home turf. Especially as she had declined the invitation to his wedding earlier that year. So in case she bumped into him in what was, after all, a small city, she should really let him know she was here.

She considered phoning him, but in the end took the easy route and sent him a text saying that she was unexpectedly in Edinburgh for a few days. The reply arrived a few minutes later.

Splendid news, Rae! You must, of course, come over and have dinner with us tomorrow night. I’ll email you details. S.

So, she was now committed. Rachel pulled on T-shirt and jeans in readiness to descend to the gilded, swagged dining room in search of food. Her phone rang just as she reached the door, and she picked up, expecting it to be Brickall.

‘Hey, you!’

Howard Davison. Her former personal trainer and boyfriend of six months.

‘Hi.’

‘I thought I’d just check up on you, since you haven’t been answering my texts. Is everything okay?’

Rachel flinched at the words ‘check up on you’ but managed to keep her tone non-combative.

‘I’m fine. I’m in Edinburgh: flew up this morning.’

‘Edinburgh? You never mentioned Edinburgh.’

‘Last minute job. Very last minute.’

‘How long for?’

‘I’m not sure: probably only a few days.’

‘I could go in and water the plants for you if you like?’

Howard had a spare key, which as far as Rachel was concerned was only for emergencies, like her locking herself out.

‘Okay… listen Howard, I’ll call you when I’m back.’

The truth was that she was glad of the chance for a break. When they first got together, Howard had recently come out of a difficult relationship and Rachel herself had not wanted anything too serious. At first this had worked well, with them spending a couple of week nights together, and most weekends.

But then she had discovered his penchant for home improvement.

Yes, in theory, it was a good thing for her functional flat conversion to be looking a bit less sterile. However, she would rather stick sharp objects in her own eyeballs than spend time trawling a DIY superstore at the weekend. Howard, on the other hand, loved it. He had continually suggested small upgrades she could make to her home and then set about installing them, extending the time they spent together to a degree that Rachel was now finding uncomfortable. The occasional weekend had morphed into every weekend. All weekend. And after the third project he had embarked on – some shelving in the entrance hall – the penny finally dropped.

He wants to move in with me.

And for Rachel, that wa. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved