- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the midst of Sarah and Frank's wedding preparations, Sarah accompanies her mother on a condolence call to the Upper West Side, where the son of family friends has died unexpectedly. The father believes his son was poisoned and would like Sarah and Frank to look into the matter. They soon learn that not everyone wants to know more about Charles' death, and they also discover that they are in the company of a very present danger.

Release date: May 5, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

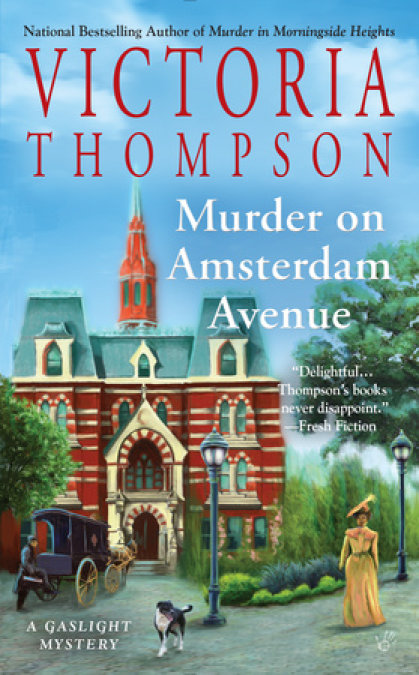

Murder on Amsterdam Avenue

Victoria Thompson

1

“Charles Oakes is dead.”

Sarah looked up at her mother in surprise. They were sitting at her kitchen table, and Sarah had spent the last half hour bringing her mother up to date on the arrangements she and her fiancé, Frank Malloy, had decided upon for their wedding and their future life. She hadn’t expected to hear about a death. “Is Charles the son? The one who was a few years older than I?”

“Sadly, yes.”

“Oh dear. I thought maybe you meant his father.”

“No, his father is Gerald.”

“How did he die? Was it an accident?”

“No, he was taken ill and . . .” Her mother shrugged. Sometimes people just died, and no one knew why. As a nurse, Sarah understood that even better than most.

“Was he married?” Sarah had lost touch with most of her old friends when she’d eloped with her first husband, a lowly physician, and turned her back on her family’s wealth and social position.

“Yes, just over a year, I believe. No children, though, which is sad because he was an only child.”

“It’s always sad when a young person dies.” Neither of them spoke of Sarah’s sister, who had died young, but Sarah could almost feel Maggie’s presence in the room.

Her mother toyed with her empty coffee cup for a moment, carefully not meeting Sarah’s eye.

“Mother, what is it?”

She sighed. “I have to pay a condolence call on the family. I was hoping you’d go with me.”

Sarah actually winced. She’d been afraid of this. Not of an old friend dying, but of being drawn back into her mother’s world of high society with its strict and meaningless rules and obligations.

“I know you haven’t seen them in years,” her mother hurried on before Sarah could protest. “But you and Mr. Malloy are going to have to find your place in society now, and starting with your old friends seems like a natural way to begin.”

“My old friend Charles is dead,” Sarah reminded her.

“You know what I mean. I know you think my life is silly—”

“Oh, Mother, I don’t—”

“Don’t bother denying it. And you’re right, a lot of the things I do aren’t very important, but you and Mr. Malloy will need friends when you marry. Maybe you think your life isn’t going to change very much just because you’ll be wealthy, but you’ll see, Sarah. People you know now won’t want to associate with you anymore. They’ll either be jealous or they’ll assume you think yourselves too good for them.”

“But we won’t!”

“Of course you won’t, but they’ll think it anyway. You’ve seen it already. Mr. Malloy had to leave the police force, and his poor mother had to leave her old neighborhood.”

Once the story of Malloy’s sudden change of fortune had appeared in the newspapers, the Malloys had indeed been forced to leave the neighborhood where they’d lived since Mrs. Malloy had come over from Ireland as a young girl. “But that was just because the reporters wouldn’t leave them alone.”

“And because all her old friends wouldn’t even speak to her anymore unless they were asking for money. Sarah, when you’re . . .” She gestured vaguely.

“Rich?” Sarah supplied.

“I was going to say a member of the privileged classes, but yes, wealthy. When you’re wealthy, the only people who feel comfortable with you are people just like you. Believe me, you will feel the same.”

As much as she hoped otherwise, Sarah was afraid her mother was right. “So paying a condolence call on the Oakes family is to be my first step back into your world?”

“It’s your world, too, or at least it was for most of your life. And yes, it could be. Charles’s widow will need friends.”

Sarah knew when she was beaten. “When did you want to go?”

“This afternoon if you’re free. I need to go home and change, and I can send the carriage back for you.”

“That’s not necessary. I’ll change here and go home with you. At least I have some appropriate clothes now.” Sarah and her mother had started buying her trousseau. As a widowed midwife, her wardrobe had been much more practical and utilitarian than fashionable, so she’d been slowly adding new items.

Less than a half hour later, Sarah had changed into a stylish suit of myrtle green batiste in deference to the early fall weather. Since Sarah’s daughter, Catherine, and her nursemaid, Maeve, were off visiting the park, they were able to get away without too much fuss.

“Do you think you’ll keep a carriage when you’re married?” her mother asked as her own carried them away from Sarah’s Bank Street home.

“Our house has a mews, although the previous owners hadn’t used the stables for a long time. Keeping horses in the city is such a lot of bother, though. Now tell me about Charles’s family. I remember there’s something unusual about his mother, but I can’t remember what.”

“She’s Southern.”

“Oh, that’s right. Where is she from again?”

“Georgia, I think.”

“Now I remember. Charles was always ashamed of that, I think, or maybe just embarrassed. He was teased, I know.”

“Of course he was. After the war, people were angry and bitter. So many young men died or were maimed, and of course they blamed the South for starting it all.”

“Well, they did start it all by seceding from the Union.”

Her mother smiled sadly. “Gerald liked to remind them that Jenny didn’t start it and that she was just as much a victim as they were. Even still, many people hated Jenny on principle, without ever bothering to meet her.”

“But how on earth did she ever get to New York in the first place?”

“Gerald sent her. Oh, it was all very romantic, although it was also very tragic.”

“Great romances are often tragic,” Sarah said. “Like Romeo and Juliet.”

“Fortunately, Gerald and Jenny’s ended much better than that one.”

“So he must have met her when he was in the army.”

“I’ve been trying to remember the whole story, but it’s been a long time since I heard it. Jenny’s family owned a plantation. I’m sure of that, at least. Gerald was with General Sherman, and of course they were burning all the plantations as they marched to the sea, so it must have been Georgia. When they got to Jenny’s home, she was the only one of her family left alive.”

“How awful! She must have been just a child.”

“Fifteen or sixteen, if I remember correctly.”

“And she was there all alone?”

“It was a plantation, so they had slaves. Some of them had stayed, but when our troops burned the house, they had no place to go, so they followed the Union army. I understand that a lot of slaves did that.”

“And Jenny went with them?”

“Apparently. I don’t remember the details. Probably, she had no choice, and at some point, Gerald noticed her. She really was a beautiful young woman. He was smitten, and he must have understood that such a beauty wouldn’t remain innocent for long when surrounded by thousands of soldiers, so he claimed her for himself.”

“Oh my, this is a romantic story. So he sent her North?”

“After he married her.”

“He married her? After just meeting her?”

“He had to, because it was the only way to ensure that his family would accept her, and even then . . . Well, as you can imagine, they were none too pleased, but what could they do? Gerald’s father had to travel down into the South to fetch her home. You can’t believe how dangerous that was during the war. They may have hoped Gerald would come to his senses when the war ended and he finally got home, but she was already with child. So they pretended not to notice the social snubs, and eventually, people got used to her.”

“And Charles was their only child.”

“Yes. I expect Jenny will be devastated.”

“And you said he was married. His wife will be, too.”

“I’m sorry to drag you into this, Sarah, but I just couldn’t bear to face it alone.”

“You could have just turned down the corner of your card and had your maid carry it in for you.” Such a gesture often replaced a visit when such a visit might be awkward or unpleasant.

Her mother’s lovely face hardened for a moment. “I couldn’t possibly do that. I know what it’s like to lose a child.”

“Oh, Mother, I’m so sorry,” Sarah said. “I didn’t think—”

“It’s all right. But it’s true. I always try to give comfort in situations like this. It’s the least I can do, no matter how little I might enjoy it. Besides, Gerald and your father have been friends since childhood. And they both belong to the Knickerbocker Club, of course. So no matter what I think of Jenny—”

“Wait, you don’t like Jenny either?”

“No, but not because she’s a Southerner. I don’t like her because I don’t like her.”

“Oh. That makes sense.”

Her mother sighed. “She’s a difficult person to know.”

“I’m sure she is, and is it any wonder? She lost her entire family and moved to a city she’d never seen before with people she’d never met who hated her on sight.”

“Southerners are supposed to be charming. She didn’t have to make it more difficult by being aloof.”

“Maybe she was just shy. Or terrified. She was still a child.”

“That was over thirty years ago. She’s no longer a child, and she can’t still be terrified.”

Sarah wondered if that were true.

• • •

The Oakes family lived on Amsterdam Avenue, just a few blocks from Sarah’s parents. The neighborhood was quietly prosperous. Understated town houses crowded the sidewalks with their marble steps before rising in stately elegance. These weren’t the monstrous mansions of the Vanderbilts or the Astors on Fifth Avenue. These were homes in which families lived for generations with the dignity, modesty, and money inherited from their thrifty Dutch ancestors.

A black wreath on the front door told the world that the Oakes family was in mourning. The maid admitted them, and after a perfunctory inquiry to see if Mrs. Oakes was “at home,” Sarah and her mother followed the maid upstairs to the formal parlor.

Not everyone could wear black well, but Sarah decided that Jenny Oakes could probably wear anything well. She must be nearing fifty, but her skin was still flawless and her melted-chocolate eyes revealed no trace of her age. Her raven hair lay completely tamed against her well-shaped head, showing no betraying gray. Sarah would have guessed her to be at least ten years younger than she must be. If Mrs. Oakes plucked the gray hairs to maintain that fiction, who could blame her?

“Jenny,” her mother was saying. “I’m so very sorry.”

Mrs. Oakes rose from where she’d been perched on the sofa in this perfectly appointed room. She wore a gown of unrelieved black, a black handkerchief clutched in one hand. She offered her cheek for Mrs. Decker’s kiss and said, “Thank you for coming, Elizabeth.”

Sarah heard just the slightest trace of the South in Mrs. Oakes’s voice. Thirty years in the North had almost worn it away.

“I’ve brought Sarah with me,” her mother said. “You remember her, don’t you?”

“Of course, although it’s been a long time, I think.”

“Yes, it has,” Sarah acknowledged, giving Mrs. Oakes her hand. The woman was a bit taller than she and held herself like a queen, although Sarah noticed in passing that her dress wasn’t new or anywhere close to it. Every society woman had a good, black dress in her wardrobe for mourning emergencies. Death struck with alarming frequency and often without warning, so one had to be prepared. Obviously, Mrs. Oakes hadn’t needed her mourning dress in quite a while. “I’m so sorry to hear about Charles. I remember him well.”

Mrs. Oakes invited them to sit down and offered them tea.

When the maid had come with it and gone again, Sarah said, “I understand Charles had been ill.”

“Not really. He . . . he thought he’d eaten something that didn’t agree with him at first, especially when he was better the next day. By the time we realized how ill he really was and sent for the doctor . . .”

Sarah watched the woman’s face for any sign of grief and saw none. If she felt the pain of her only son’s loss, she hid it well. Of course, her mother would remind her of the lessons of her youth when she was taught it was unseemly to show emotions.

Her mother was murmuring something sympathetic when the parlor doors opened. A young woman wearing a very new and stylish black gown stepped into the room. The widow, Sarah guessed, although she didn’t look particularly grief stricken. She seemed pretty enough, although her petulant expression made it hard to really tell.

“Elizabeth, you remember my daughter-in-law, Hannah, don’t you? She was a Kingsley.”

Sarah had almost forgotten the habit the old families had of giving a person’s pedigree.

Jenny introduced her guests. Hannah nodded stiffly at Elizabeth, then glanced at Sarah before silently dismissing her as someone of no importance. Then she made her way over and dutifully sat down on the sofa beside her mother-in-law. She was at least five years younger than Sarah, so their paths would never have crossed growing up. If she had been weeping for her dead husband, her eyes gave no indication of it.

Sarah’s mother offered her condolences, but Hannah hadn’t quite mastered her mother-in-law’s restraint.

“Someone should be sorry for me,” she snapped. “It’s all so unfair.”

Jenny gave her a sharp glance but Hannah never saw it.

“We were invited to go to Newport this summer,” she continued, “but Charles said we couldn’t go. Now we’re in mourning, and I won’t be able to go anyplace at all for a whole year.”

“Charles didn’t die just to inconvenience you, my dear,” Jenny said with the barest trace of venom.

Sarah glanced at her mother, whose wide eyes betrayed her shock at such inappropriate behavior. She tried to smooth things over. “I’m sure not going to Newport was a disappointment.”

“It certainly was,” Hannah said. “And the worst part was that we couldn’t go because Charles said he had to go to work.”

“Charles had been appointed superintendent of the Manhattan State Hospital,” Jenny said, giving Hannah another glare, although Hannah didn’t appear to notice.

“Yes, I saw it mentioned in the newspapers,” Sarah’s mother said. “It was a very nice write-up about him and the hospital, too.”

“They call it a hospital,” Hannah said, “but it’s really an asylum. A place for crazy people. Can you imagine? What would Charles know about crazy people?”

“It was an administrative position,” Jenny said, more to Sarah and her mother than to Hannah. “His job was to manage the institution, not deal with the patients.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Hannah said. “I still don’t know why we couldn’t go to Newport. The season there is only two months. That’s not very long to be away.”

Sarah’s mother had had enough of Hannah. She turned back to Jenny. “I remember hearing about Charles’s appointment. You must have been very proud.”

Some emotion Sarah couldn’t identify flickered over Jenny’s face, causing a tightness around her mouth. “Charles has many friends in the city.”

Or maybe she wasn’t so proud.

Sarah’s mother quickly began inquiring about funeral arrangements, which seemed cheerful by comparison to Hannah’s inappropriate bitterness over her husband’s inconvenient death. They managed to finish their visit without another outburst from the young widow, and gratefully followed the maid who came to show them out.

Sarah was quietly wondering if it was possible for her to withdraw from society completely after she and Malloy married, when the maid startled them both by stopping dead in her tracks. She turned to face them instead of leading them down the stairs.

“Excuse me, Mrs. Decker, but Mr. Oakes asked if you could see him in the library for a few minutes before you leave.”

“Why, certainly,” she replied, giving Sarah a puzzled glance. “My daughter, too?”

“Yes, ma’am. This way, please.”

She led them down the hallway, away from the stairs that would have taken them to the front door at street level. She opened one of the doors and announced them.

The library was a comfortable room with large leather armchairs and rows of bookshelves. The air smelled faintly of tobacco. A middle-aged man greeted them warmly. Sarah’s mother gave him both her hands and offered her cheek for a kiss.

“I’m so terribly sorry, Gerald,” she said.

“It’s a cruel trick of fate when a child dies,” he said, blinking at the tears neither his wife nor his daughter-in-law had bothered to shed. “You expect to bury your parents, but never your children.”

“I know,” she said, and Sarah knew she did. “You remember my daughter, Sarah.”

“Of course. Mrs. Brandt, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Sarah said in surprise. He would have had no reason to have remembered her married name. She expressed her condolences, and he thanked her.

“Please, sit down. I won’t keep you long, but I have a favor to ask.”

They each took one of the armchairs that sat grouped together in front of the unlit fireplace. The soft leather enveloped Sarah, and she thought perhaps she should get some chairs like this for her new house. She would have to mention it to Malloy.

“You know we’ll be happy to do anything for you and Jenny, Gerald,” her mother was saying. “All you need to do is ask.”

“Actually, Mrs. Brandt is the one I must ask,” he said.

“Me?” Sarah asked in surprise.

“Well, you and your fiancé. You’re engaged to Frank Malloy, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” she said, thinking he couldn’t possibly have remembered that tidbit of information from casually reading the society pages of the newspapers.

“I know what Mr. Malloy did for the club, Mrs. Brandt. The Knickerbocker Club,” he added in case she didn’t know. “He handled a sensitive situation discreetly, and all the members were very grateful.”

“I’ll be sure and tell him you said so.”

“Please do. And of course we know about his . . . his recent good fortune. As you can imagine, it has been a topic of interest to all of us.”

“I can easily imagine that,” Sarah said with a small smile. It had been a topic of interest to many people.

“I say all this so you know that I understand he is no longer with the police and that he no longer needs to earn his living, but I am wondering if you think he would be willing to assist me in another matter that is even more sensitive than the one he handled at the club.”

Sarah’s mind was racing as she tried to figure out where this conversation was taking her. “I really can’t speak for Mr. Malloy,” she hedged, although she could easily imagine he would be thrilled to do anything besides oversee the renovations to their house, which had been his sole occupation for the past few months. “But I will be happy to pass along your request. Can you give me some idea of what you’d like him to help you with?”

“Yes. I’d like him to investigate my son’s murder.”

• • •

At first Frank thought the knocking was just more hammering from the workmen who were somewhere in the bowels of his monstrosity of a house doing something to, hopefully, make it fit for habitation, if he lived long enough to ever see the end of it. He tried to remind himself that eventually, the house would be finished, and he and Sarah would be married, and she’d live here with him. Unfortunately, he’d begun to give up hope that would ever happen, because, at this rate, the house was never going to be finished.

After a few minutes, he finally realized the knocking was coming from the front door, though, and he made his way to answer it.

The front hallway didn’t look too bad, he acknowledged, glancing around as he approached the door. Except for some dust, which was unavoidable as long as the workmen were here, it was almost presentable. If only the doorbell worked. He’d asked the workmen to fix it at least a dozen times, to no avail. Who knows how many visitors had given up and gone away because he hadn’t heard them knock? A lot, he hoped, since the only people who knocked on his door nowadays were reporters looking for a story or people looking for a handout.

Frank threw open the door, ready to do battle with whoever was there to ask him for something, and he caught himself just in time. “Sarah.”

She smiled the way she always smiled when she saw him, and he had to resist the overwhelming urge to take her in his arms, because her mother was standing right beside her.

“Mrs. Decker, how nice to see you.” He stood back and motioned them inside.

“It’s lovely to see you, too,” Mrs. Decker said.

Sarah gave him a peck on the cheek and a knowing smirk as she passed. Both women looked around appreciatively as he closed the door behind them.

“It’s starting to look very nice,” Mrs. Decker said.

Just then someone upstairs started pounding, raising a deafening racket. Frank motioned them into the room he’d just left and closed the door. They could still hear the pounding, but they could also now hear one another, too.

“This is going to be Mrs. Malloy’s sitting room,” Sarah told her mother. “And her bedroom is through there. We made her a suite down here so she wouldn’t have to manage the stairs.”

“It’s lovely,” Mrs. Decker said.

“She made me bring all her old furniture,” Frank felt obligated to explain, because it didn’t really look that lovely.

“Which was very sensible,” Mrs. Decker said, always the lady. “You wouldn’t want to put anything new in here until the workmen are finished. Where is your mother?”

“She’s at school with Brian.”

“She still stays with him every day?”

“She helps out there,” Frank explained, “and she’s learning to sign, too, so she can talk to him.”

“That’s such a wonderful thing,” Mrs. Decker said. “We should all learn to sign now that Brian will be a member of our family.”

Frank knew he was probably gaping at her in surprise at the thought that she would actually want to learn sign language to talk with his deaf son, but she was much too polite to notice.

“Uh, why don’t you sit down,” he managed after a moment. “Can I get you something?”

“Oh my, no. I wouldn’t think of sending you to the kitchen for anything,” Sarah said, still giving him that knowing smirk as she and her mother sat down on his mother’s old sofa. “Besides, we’re here on business.”

“What kind of business?”

“Gerald Oakes wants to hire you to investigate his son’s murder.”

“Possible murder,” Mrs. Decker added quickly. “Actually, he wants you to figure out if his son was murdered or if he died a natural death.”

Frank sank down in one of his mother’s old chairs. “Who is Gerald Oakes?”

“He’s a member of the Knickerbocker Club,” Sarah said.

“And an old friend of our family,” Mrs. Decker said.

“And he knows all about you and what you did for the club,” Sarah said.

“And he also knows your current situation,” Mrs. Decker said, “so he didn’t want to insult you by offering to hire you, but he thought you would appreciate a businesslike arrangement of some sort.”

The women were making him a little dizzy. “You said he wants to find out if his son was murdered. How did he die?”

“It was sudden,” Sarah explained. She looked especially beautiful today, he noticed, but then, he thought she looked especially beautiful every day. “He became ill, vomiting and other unpleasant things, apparently.”

“He thought he’d eaten something bad,” Mrs. Decker said.

“When he didn’t get any better over the next few days, they called in the doctor, but he died shortly afterward.”

“So Oakes thinks his son was poisoned?” Frank asked.

“Wouldn’t you?” Mrs. Decker asked.

He gave her a tolerant smile. “It probably wouldn’t be my first thought unless I had a reason to think someone wanted him dead. Did someone want this fellow . . . What’s his name?”

“Charles Oakes,” Sarah said. “He’s . . . he was only a few years older than I, and otherwise in good health.”

“Tell him about the milk,” Mrs. Decker said.

“Yes, tell me about the milk,” he said with a grin.

“The night he died, he’d asked for a glass of warm milk,” Sarah said. “He drank most of it, and at some point later, while the doctor was working on him, the glass got knocked over. No one noticed it until the next morning.”

“There wasn’t much milk left, apparently,” Mrs. Decker said, “but the cat—his wife has this pet cat—had apparently lapped up what was left.”

“And they found the cat under Charles’s bed, dead,” Sarah said.

“After the undertaker had come for Charles’s body the next morning,” Mrs. Decker added.

“That’s interesting,” Frank said.

“Of course, it doesn’t prove anything,” Sarah said. “Sometimes cats just die.”

“And sometimes people just die,” Mrs. Decker said.

“But when they both die after drinking the same glass of milk, you have to wonder,” Frank said.

“Exactly,” Mrs. Decker said.

She looked much too excited for somebody talking about an old friend being poisoned. Frank knew he shouldn’t encourage her morbid fascination, but he couldn’t help himself. “What did the doctor say?”

“He said gastric fever. He didn’t know about the cat, of course,” Mrs. Decker said.

“I asked Mr. Oakes where they took the body, and he said it’s at a funeral home now,” Sarah said.

“So they didn’t do an autopsy?” he asked.

Sarah shook her head. “No, and it’s probably too late now, isn’t it?”

“If the body is already embalmed . . .” Frank shrugged.

“And the milk glass has long since been washed and put away,” Sarah said.

“Does Mr. Oakes have any reason to think somebody wanted his son dead?”

The two women exchanged a glance, then Sarah said, “He didn’t want to discuss that with two gently bred ladies, but I think if you are willing to help him, he would discuss it with you.”

“If there’s no proof he was poisoned, I don’t know what I can do,” Frank said.

At some point, the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...