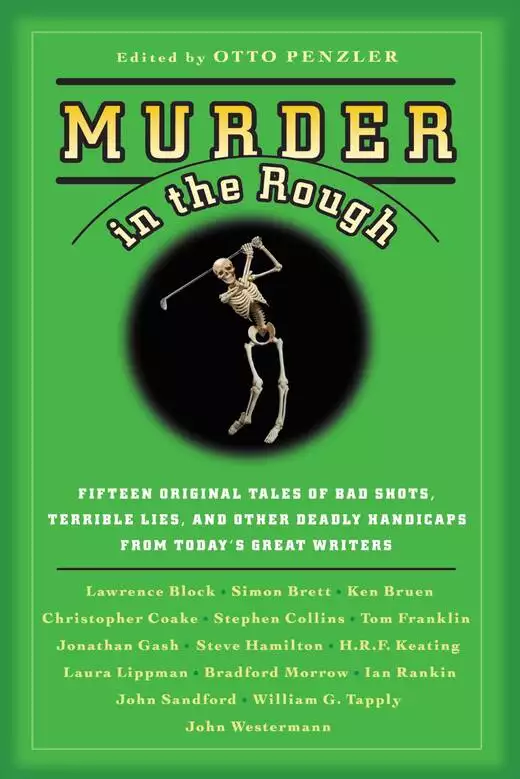

Murder in the Rough

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

This the fourth title in a sports mystery series edited by Otto Penzler. Lawrence Block, Simon Brett, HRF Keating, Ian Rankin and many others deliver up an ace anthology of original short stories that mix murder and mystery on the fairway. This collection is sure to appeal to sports fans and those eager to read stories by the most celebrated authors in the mystery genre.

Release date: June 21, 2006

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder in the Rough

Otto Penzler

that the greatest sportswriting should be about golf. Or Ping-Pong.

Try as I might, I could not convince my publisher that a book collecting Ping-Pong mystery stories was just what the world

is waiting for, which is just as well, because when I raised the subject with some of the world’s top crime writers, they

looked at me as if I had finally taken that last step over the edge of sanity.

Golf is a different kettle of mackerel, however. It seems that an astonishing number of people who earn their living by putting

words on paper in an appealing way have tried their hands at putting a little white ball into a cup cut into a very large

and very green lawn. They also liked the notion of writing about it and the violence it can engender.

There is a long and distinguished history of golf in mystery fiction, with such giants of the genre as Agatha Christie, James

Ellroy, Ian Fleming, Michael Innes, and Rex Stout having produced

classic works in which golf figures prominently. At the back of the book is a comprehensive list of titles for further reading

or collecting—the most complete bibliography of golf mysteries ever compiled.

Mystery writers have used numerous golf course settings as homes for their corpses: in the rough, in a sand trap, even right

there on the green. And the methods and devices used to finish off their hapless victims have been as varied as your previous

ten tee shots, including exploding balls, exploding golf clubs, an exploding cup, and even an exploding golf course. Victims

have been speared with a flag stick, clubbed with a, yes, golf club, and murdered in a sabotaged golf cart. Most bodies attained

their status as the formerly living in more ordinary ways, such as being shot, garroted, or stabbed on a golf course before,

during, or after a game.

Happily, none of the authors in Murder in the Rough have used exploding devices to dispatch their victims, but you will encounter in these pages some fascinating motives for

murder and any number of memorable characters created by the champions of today’s mystery writing world.

Lawrence Block has received the two top awards it is possible to receive in the mystery community: a Grand Master Award from

the Mystery Writers of America and the Diamond Dagger from the (British) Crime Writers’ Association, both for lifetime achievement.

Simon Brett has remained a popular crime novelist for thirty years, most memorably for his work featuring Charles Paris, a

frequently out-of-work actor who enjoys the bottle as much as he enjoys solving mysteries; he made his debut in Cast in Order of Disappearance (1975).

Ken Bruen, one of the hardest of the hard-boiled writers

working today, is the author of twenty novels. He has been nominated for an Edgar and won the Shamus Award from the Private

Eye Writers of America for The Guards, which introduced Jack Taylor, his Galway-based P.I.

Christopher Coake, who recently got his M.F.A. from Ohio State University, has already published a short story collection

with Harcourt, We’re in Trouble, which contains “All Through the House,” which was selected for Best American Mystery Stories 2004.

Stephen Collins is the author of two suspense novels, Eye Contact (1994) and Double Exposure (1998), but is best known as an actor in the long-running television series 7th Heaven and in such films as All the President’s Men, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and The First Wives Club.

Tom Franklin won the Edgar Allan Poe Award for his short story “Poachers” in 1999; it became the title story for his first

book, Poachers and Other Stories, which was followed by his critically applauded first novel, Hell at the Breech.

Jonathan Gash, a physician in real life and one of England’s foremost experts in tropical diseases, is most famous for his

series about Lovejoy, the not-overly-scrupulous dealer in antiques, portrayed for several seasons by Ian McShane in the popular

television program.

Steve Hamilton’s first novel, A Cold Day in Paradise, won the Edgar and Shamus awards. Like his subsequent novels, it featured Alex McKnight, the former northern Michigan cop

who reluctantly becomes involved with cases to help or protect friends.

H. R. F. Keating is one of the Grand Old Men of the detective novel, having written several distinguished critical works about

Sherlock Holmes and crime fiction, plus more

than fifty novels, most famously those featuring Ganesh Ghote of the Bombay police force.

Laura Lippman, formerly a reporter and feature writer for the Baltimore Sun, has been nominated frequently for all the major mystery awards, winning the Edgar for Charm City in 1998. All of her books are set in her much-loved Baltimore and feature Tess Monaghan.

Bradford Morrow was described by Publishers Weekly as “one of America’s major literary voices.” The founder and editor of the literary journal Conjunctions, he was given the Academy Award in Literature by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Ian Rankin and his series hero, the Edinburgh policeman John Rebus, have become so popular that Rankin is in The Guinness Book of World Records for having seven books in the top ten in England at the same time. He won the Edgar in 2004 for Resurrection Men.

John Sandford, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is a perennial on the best-seller list with his Prey novels featuring Lucas Davenport, the Twin Cities policeman who is unlike most cops in that he likes to work alone, drives

a Porsche, and creates video games in his spare time.

William G. Tapply has a successful career as a columnist for Field & Stream and as the author of several books on fly fishing, but it is his series of novels about Brady Coyne, the kindly Boston lawyer

who functions as a private detective, that endears him to mystery readers.

John Westermann is of the Joseph Wambaugh school of writers about police officers, except that he focuses on dirty cops and

corruption. His novel Exit Wounds was filmed with

Steven Seagal as Orin Boyd and opened in 2001 as the number one box-office hit in America.

So it seems appropriate to say welcome to the Masters (though Murder in the Rough allows women to participate).

—Otto Penzler

New York, June 2005

Lawrence Block

Kramer liked routine.

Always had. He’d worked at Taggart & Leeds for thirty-five years, relieved to settle in there after spending his twenties

hopping from one job to another. His duties from day to day were interesting enough to keep him engaged, but in a sense they

were the same thing—or the same several things—over and over, and that was fine with him.

His wife made him the same breakfast every weekday morning for those thirty-five years. Breakfast, he had learned, was the

one meal where most people preferred the same thing every time, and he was no exception. A small glass of orange juice, three

scrambled eggs, two strips of bacon, one slice of buttered toast, a cup of coffee—that did him just fine.

These days, of course, he prepared it himself. He hadn’t needed to learn how—he’d always made breakfast for both of them on

Saturdays—and now the time he spent whisking eggs in a bowl and turning rashers with a fork was a time for him to think of

her and regret her passing.

So sudden it had been. He’d retired, and she’d said, in mock

consternation, “Now what am I going to do with you? Am I going to have you underfoot all day every day?” And he established

a routine that got him out of the house five days a week, and they both settled gratefully into that routine, and then she

felt a pain and experienced a shortness of breath and went to the doctor, and a month later she was dead.

He had his routine, and it was clear to him that he owed his life to it. He got up each morning, he made his breakfast, he

washed the dishes by hand, he read the paper along with a second cup of coffee, and he got out of the house. Whatever day

it was, he had something to do, and his salvation lay in doing it.

If it was Monday, he walked to his gym. He changed from his street clothes to a pair of running shorts and a singlet, both

of them a triumph of technology, made of some miracle fiber that wicked moisture away from the skin and sent it off somewhere

to evaporate. He put his heavy street shoes in his locker and laced up his running shoes. Then he went out on the floor, where

he warmed up for ten minutes on the elliptical trainer before moving to the treadmill. He set the pace at twelve-minute miles,

set the time at sixty minutes, and got to it.

Kramer, who’d always been physically active and never made a habit of overeating, had put on no more than five pounds in the

course of his thirty-five years at Taggart & Leeds. He’d added another couple of pounds since then, but at the same time had

lost an inch in the waistline. He had lost some fat and gained a little muscle, which was the point, or part of it. The other

part, perhaps the greater part, was having something enjoyable and purposeful to do on Mondays.

On Tuesdays he turned in the other direction when he left his apartment, and walked three-quarters of a mile to the Bat Cave,

which was not where you would find Batman and Robin,

as the name might lead you to expect, but instead was a recreational facility for baseball enthusiasts. Each of two dozen

batting cages sported a pitching machine the standard sixty feet from home plate, where the participant dug in and took his

cuts for a predetermined period of time.

They supplied bats, of course, but Kramer brought his own, a Louisville Slugger he’d picked out of an extensive display at

a sporting goods store on Broadway. It was a little heavier than average, and he liked the way it was balanced. It just felt

right in his hands. Also, there was something to be said for having the same bat every time. You didn’t have to adjust to

a new piece of lumber.

He brought along cleated baseball shoes, too, which made it easier to establish his stance in the batter’s box. The boat-necked

shirt and sweatpants he wore didn’t sport any team logo, which would have struck him as ridiculous, but they were otherwise

not unlike what the pros wore, for the freedom of movement they afforded.

Kramer wore a baseball cap, too; he’d found it in the back of his closet, had no idea where it came from, and recognized the

embroidered logo as that of an advertising agency that had gone out of business some fifteen years ago. It must have come

into his possession as some sort of corporate party favor, and he must have tossed it in his closet instead of tossing it

in the trash, and now it had turned out to be useful.

You could set the speed of the pitching machine, and Kramer set it at Slow at the beginning of each Tuesday session, turned

it to Medium about halfway through, and finished with a few minutes of Fast pitching. He was, not surprisingly, better at

getting his bat on the slower pitches. A fastball, even when you knew it was coming, was hard for a man his age to connect

with. Still, he hit most of the medium-speed pitches—some solidly, some less so. And he always got some wood on some of the

fastballs, and every once in a while he’d meet a high-speed pitch solidly, his body turning into the ball just right, and

the satisfaction of seeing the horsehide sphere leap from his bat was enough to cast a warm glow over the entire morning’s

work. His best efforts, he realized, were line drives a major-league center fielder would gather in without breaking a sweat,

but so what? He wasn’t having fantasies of showing up in Sarasota during spring training, aiming for a tryout. He was a sixty-eight-year-old

retired businessman keeping in shape and filling his hours, and when he got ahold of one, well, it felt damned good.

Walking home, carrying the bat and wearing the ball cap, with a pleasant ache in his lats and delts and triceps—well, that

felt pretty good, too.

Wednesdays provided a very different sort of exercise. Physically, he probably got the most benefit from the walk there and

back—a couple of miles from his door to the Murray Street premises of the Downtown Gun Club. The hour he devoted to rifle

and pistol practice demanded no special wardrobe, and he wore whatever street clothes suited the season, along with a pair

of ear protectors the club was happy to provide. As a member, he could also use one of the club’s guns, but hardly anyone

did; like his fellows, Kramer kept his own guns at the club, thus obviating him of the need to obtain a carry permit for them.

The license to own a weapon and maintain it at a recognized marksmanship facility was pretty much a formality, and Kramer

had obtained it with no difficulty. He owned three guns—a deer rifle, a .22-caliber target pistol, and a hefty .357 Magnum

revolver.

Typically, he fired each gun for half an hour, pumping lead at (and occasionally into) a succession of paper targets. He could

vary the distance of the targets, and naturally chose the greatest distance for the rifle, the least for the Magnum. But he

would sometimes bring the targets in closer, for the satisfaction of grouping his shots closer, and would sometimes increase

the distance, in order to give himself more of a challenge.

Except for basic training, some fifty years ago, he’d never had a gun in his hand, let alone fired one. He’d always thought

it was something he might enjoy, and in retirement he’d proved the suspicion true. He liked squeezing off shots with the rifle,

liked the balance and precision of the target pistol, and even liked the nasty kick of the big revolver and the sense of power

that came with it. His eye was better some days than others, his hand steadier, but all in all it seemed to him that he was

improving. Every Wednesday, on the long walk home, he felt he’d accomplished something. And, curiously, he felt empowered

and invulnerable, as if he were actually carrying the Magnum on his hip.

Thursdays saw him returning to the gym, but he didn’t warm up on the elliptical trainer, nor did he put in an hour on the

treadmill. That was Monday. Thursday was for weights.

He did his circuit on the machines. Early on, he’d had a couple of sessions with a personal trainer, but only until he’d managed

to establish a routine that he could perform without assistance. He kept a pocket notebook in his locker, jotting down the

reps and poundages on each machine; when an exercise became too easy, he upped the weight. He was making slow but undeniable

progress. He could see it in his notes, and, more graphically, he could see it in the mirror.

His gym gear made it easy to see, too. The shorts and singlet

that served so well on Mondays were not right for Thursdays, when he donned instead a pair of black spandex bicycle shorts

and a matching tank top. It made him look the part, but that was the least of it. The close fit seemed to help enlist his

muscles to put maximum effort into each lift. His weight-lifting gloves, padded slightly in the palms for cushioning, and

with the fingers ending at the first knuckle joint for a good grip, kept him from getting blisters or calluses, as well as

telling the world that he was serious enough about what he was doing to get the right gear for it.

An hour with the weights left him with sore muscles, but ten minutes in the steam room and a cold shower set him right again,

and he always felt good on the way home. And then, on Fridays, he got to play golf.

And that was always a pleasure. Until Bellerman, that interfering son of a bitch, came along and ruined the whole thing for

him.

The driving range was at Chelsea Piers, and it was a remarkable facility. Kramer had made arrangements to keep a set of clubs

there, and he picked them up along with his usual bucket of balls and headed for the tee. When he got there, he put on a pair

of golf shoes, arguably an unnecessary refinement on the range’s mats, but he felt they grounded his stance. And, like the

thin leather gloves he kept in his bag, they put him more in the mood, as did the billed tam-o’-shanter cap he’d put on his

head before leaving the house.

He teed up a ball, took his Big Bertha driver from the bag, settled himself, and took a swing. He met the ball solidly, but

perhaps he’d dropped his shoulder, or perhaps he’d let his

hands get out in front; in any event, he sliced the shot. It wasn’t awful—it had some distance on it and wouldn’t have wound

up all that deep in the rough—but he could do better. And did so on the next shot, again meeting the ball solidly and sending

it out there straight as a die.

He hit a dozen balls with Big Bertha, then returned her to the bag and got out his spoon. He liked the 3-wood, liked the balance

of it, and he had to remind himself to stop after a dozen balls or he might have run all the way through the bag with that

club. It was, he’d found, a very satisfying club to hit.

Which was by no means the case with the 2-iron. It wasn’t quite as difficult as the longest iron in his bag—there was a joke

he’d heard, the punch line of which explained that not even God could hit the 1-iron—but it was difficult enough, and today

his dozen attempts with the club yielded his usual share of hooks and slices and topped rollers. But among them he hit the

ball solidly twice, resulting in shots that leaped from the tee, scoring high for distance and accuracy.

And therein lay the joy of the sport. One good shot invariably erased the memory of all the bad shots that preceded it, and

even took the sting out of the bad shots yet to come.

Today was an even-irons day, so in turn he hit the 4-iron, the 6-iron, and the 8-iron. When he finished with the niblick (he

liked the old names, called the 2-wood a brassie and the 3-wood a spoon, called the 5-iron a mashie, the 8 a niblick), he

had four balls left of the seventy-five he’d started with. That suggested that he’d miscounted, which was certainly possible,

but it was just as likely that they’d given him seventy-six instead of seventy-five, since they gave you what the bucket held

instead of delegating some minion to count them. He hit the four balls with his wedge, not the most

exciting club to hit off a practice tee, but you had to play the whole game, and the short game was vital. (He had a sand

wedge in his bag, but until they added a sandpit to the tee, there was no way he could practice with it. So be it, he’d decided;

life was compromise.)

He left the tee and went to the putting green, where he put in his usual half hour. His putter was an antique, an old wooden-shafted

affair with some real collector value, his choice on even-iron Fridays. It seemed to him that his stroke was firmer and more

accurate with the putter from his matched set, his odd-iron choice, but he just liked the feel of the old club, and something

in him responded to the notion of using a putter that could have been used a century ago at St. Andrews. He didn’t think it

had, but it could have been, and that seemed to mean something to him.

His putting was erratic—it generally was—but he sank a couple of long ones and ended the half hour with a seven-footer that

lipped the cup, poised on the brink, and at last had the decency to drop. Perfect! He went to the desk for his second bucket

of balls and returned to the tee and his Big Bertha.

He’d worked his way down to the 6-iron when a voice said, “By God, you’re good. Kramer, I had no idea.”

He turned and recognized Bellerman. A coworker at Taggart & Leeds, until some competing firm had made him a better offer.

But now, it turned out, Bellerman was retired himself, and improving the idle hour at the driving range.

“And you’re serious,” Bellerman went on. “I’ve been watching you. Most guys come out here and all they do is practice with

the driver. Which they then get to use one time only on the long holes and not at all on the par 3s. But you work your way

through the bag, don’t you?”

Kramer found himself explaining about even- and odd-iron days.

“Remarkable. And you hit your share of good shots, I have to say that. Get some good distance with the long clubs, too. What’s

your handicap?”

“I don’t have one.”

Bellerman’s eyes widened. “Jesus, you’re a scratch golfer? Now I’m more impressed than ever.”

“No,” Kramer said. “I’m sure I would have a handicap, but I don’t know what it would be. See, I don’t actually play.”

“What do you mean you don’t play?”

“I just come here,” Kramer said. “Once a week.”

“Even-numbered irons one week, odd ones the next.”

“That’s right.”

“Every Friday.”

“Yes.”

“You’re kidding me,” Bellerman said. “Right?”

“No, I—”

“You practice more diligently than anybody I’ve ever seen. You even hit the fucking 1-iron every other Friday, and that’s

more than God does. You work on your short game, you use the wedge off the tee, and for what? So that you won’t lose your

edge for the following Friday? Kramer, when was the last time you actually got out on a course and played a real round of

golf?”

“You have to understand my routine,” Kramer said. “Golf is just one of my interests. Mondays I go to the gym and put in an

hour on the treadmill. Tuesdays I go to the batting cage and work my way up to fastballs. Wednesdays…” He made his way through

his week, trying not to be thrown off stride by the expression of incredulity on Bellerman’s face.

“That’s quite a system,” Bellerman said. “And it sounds fine for the first four days, but golf… Man, you’re practicing when

you could be playing! Golf’s an amazing game, Kramer, and there’s more to it than swinging the club. You’re out in the fresh

air—”

“The air’s good here.”

“—feeling the sun on your skin and the wind in your hair. You’re on a golf course, the kind of place that gives you an idea

of what God would have done if he’d had the money. And every shot presents you with a different kind of challenge. You’re

not just trying to hit the ball straight and far. You’re dealing with obstacles, you’re pitting your ability against a particular

aspect of terrain and course conditions. I asked you something earlier, and you never answered. When’s the last time you played

a round?”

“Well, as a matter of fact—”

“You never did, did you?”

“No, but—”

“Tomorrow morning,” Bellerman said, “you’ll be my guest, at my club on the Island. I’ve got tee time booked at 7:35. I’ll

pick you up at six. That’ll give us plenty of time.”

“I can’t.”

“You’re retired, for chrissake. And tomorrow’s Saturday. It won’t keep you from your weekday schedule. You really can’t? All

right, then, a week from tomorrow. Six o’clock sharp.”

Kramer spent the week trying not to think about it and then, when that didn’t work, trying to think of a way out. He didn’t

hear from Bellerman and found himself hoping the man would have forgotten the whole thing.

His routine worked, and he saw no reason to depart from it. Maybe he wasn’t playing “real” golf, maybe he was missing something

by not getting out on an actual golf course, but he got more than enough pleasure out of the game the way he played it. There

were no water hazards, there were no balls lost in deep rough, and there was no score to keep. He got the exercise—he took

more swings at the driving range than anyone would take in eighteen holes on a golf course—and he got the occasional satisfaction

of a perfect shot, without the crushing dismay that could attend a horrible shot.

Maybe Bellerman would realize that the last thing he wanted to do was waste a morning playing with Kramer.

And yet, when Kramer was back at the range that Friday, he felt vaguely sorry (if more than slightly relieved) that he hadn’t

heard from the man. He knew how much he’d improved in recent months, hitting every club reasonably well (including, this particular

day, the notorious 1-iron), and, of course, it would be different on a golf course, but how different could it be? You had

the same clubs to swing, and you tried to make the ball go where you wanted it.

And just suppose he turned out to be good at it. Suppose he was good enough to give Bellerman a game. Suppose, by God, he

could beat the man.

Sort of a shame he wasn’t going to get the chance…

“Good shot,” said a familiar voice. “Hit a few like that tomorrow and you’ll do just fine. Don’t forget, I’m coming for you

at six. So remember to take your clubs home when you’re done here today. And make sure you’ve got enough golf balls. Kramer?

I’ll bet you don’t have any golf balls, do you? Ha! Well, buy a dozen. They’re accommodating at my club, but they won’t hand

you a bucketful.”

On the way there, Bellerman told him he’d read about Japanese golfers who spent all their time on driving ranges and putting

greens. “Practicing for a day that never comes,” he said. “It’s the cost of land there. It’s scarce, so there aren’t many

golf courses, and club dues and greens fees are prohibitive unless you’re in top management. Actually, the driving-range golfers

do get to play when they’re on vacation. They’ll go to an all-inclusive resort in Hawaii or the Caribbean and play thirty-six

holes a day for a solid week, then go home and spend the rest of the year in a cage, hitting balls off a tee. Well, today’s

your vacation, Kramer, and you don’t have to cross an ocean. All you have to do is tee up and hit the ball.”

It was a nightmare.

And it began on the very first tee. Bellerman went first, hitting a shot that wouldn’t get him in trouble, maybe 150 yards

down the fairway with a little fade at the end that took some of the distance off it.

Then it was Kramer’s turn, and he placed a brand-new Titleist on a brand-new yellow tee and drew his Big Bertha from his bag.

He settled himself, rocking to get his cleated feet properly planted, and addressed the ball, telling himself not to kill

it, just to meet it solidly. But he must have been too eager to see where the ball went, because he looked up prematurely,

topping the ball. That happened occasionally at Chelsea Piers, and the result was generally a grounder. This time, however,

he really topped the thing, and it caromed up into the air like a Baltimore chop in baseball, coming to earth perhaps a hundred

feet away, right where a shortstop would have had an effortless time gathering it in.

Bellerman didn’t laugh. And that was worse, somehow, than if he had.

By the third hole, Kramer was just waiting for it to be over. He’d taken an 8 on the first hole and a 9 on the second, and

at this rate he seemed likely to wind up with a score somewhere north of 150 for the eighteen holes Bellerman intended for

them to play. That meant, he calculated, around 130 strokes to go, 130 more swings of one club or another. He could just go

through it, a stroke at a time, and then it would be over, and he would never have to go through anything like this again.

“Good shot!” Bellerman said when Kramer’s fourth shot on 3, with his trusty niblick, actually hit the green and stayed there.

“That’s the thing about this game, Kramer. I can four-putt a green, then shank my drive and put my second shot in a bunker,

but one good shot and everything feels right. Isn’t it a good feeling?”

It was, sort of, but he knew it wouldn’t last, and it had begun to fade by the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...