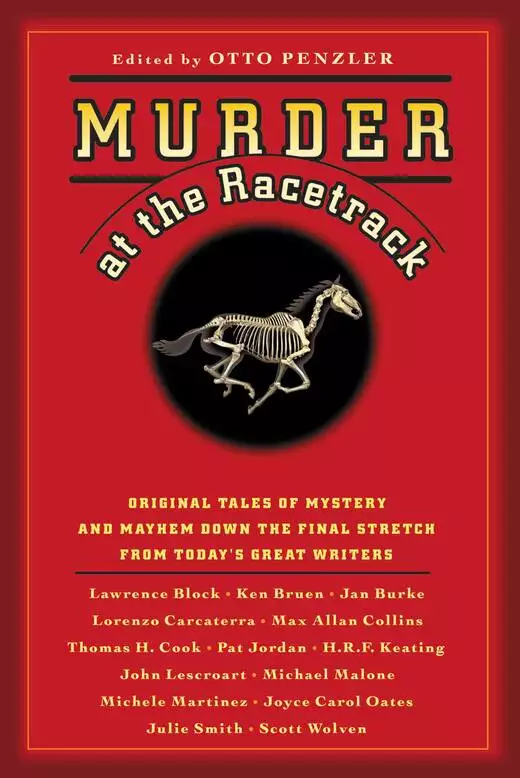

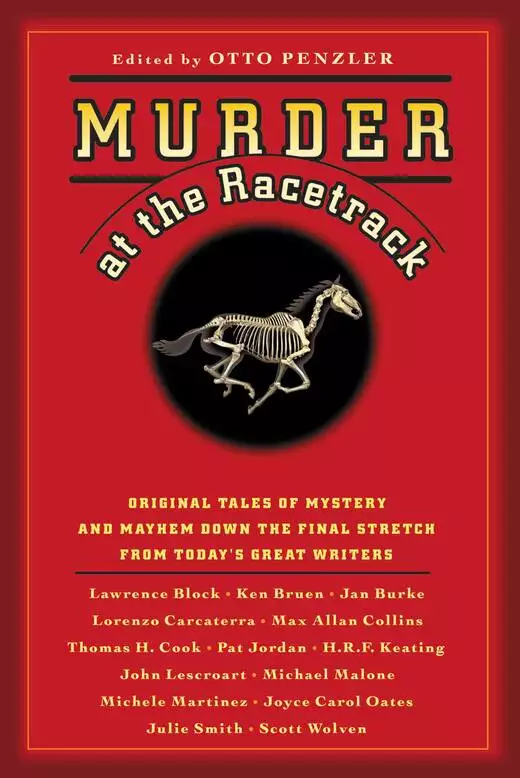

Murder at the Racetrack

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

An anthology of 13 racetrack mysteries containing original short stories, centered on horseracing, by the following authors: Joyce Carol Oates, H.R.F. Keating, John Lescroart, Lorenzo Carcaterra, Lawrence Block, Ken Bruen, Jan Burke, Max Allan Collins, Thomas H. Cook, Pat Jordan, Michael Malone, Michele Martinez, Julie Smith, and Scott Wolven.

Release date: September 26, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder at the Racetrack

Otto Penzler

What is it about horse racing that makes it seem so out of kilter? Here we have exquisitely beautiful animals upon whom are

lavished all the care that most men don’t even offer their wives. It ’s an outdoor sport, mainly reserved for warm sunny days,

with bright green lawns in the infield and leafy old trees beyond.

Yet if there’s a dirtier sport than horse racing, one with more fixes than Needle Park (and let’s get this straight—professional

wrestling has as much to do with sports as Dennis Rodman has to do with splitting the atom), I have yet to discover it. Even

boxing, which has the reputation of being crooked, is purer than a seven-year-old Pakistani bride compared with “the Sport

of Kings.”

There are good reasons for an owner to want his horse to lose a race. The more times a big old stallion steps into the gate

and comes up short, the longer the odds are for the next race. A sudden victory with long odds can pay off very handsomely

if a clever fellow has placed a substantial bet on that very outcome.

It’s almost impossible to count the ways in which an owner (or a trainer, not to mention the occasional jockey) can stop a

horse from winning. Various chemicals can slow down a horse, and so can the wrong food. A long run in the middle of the night

probably won’t have a positive effect on a horse’s stamina the next afternoon. You don’t want to know what a sponge shoved

way up a horse’s nose will do to the poor critter. There are other methods of killing a racer’s chances of a first-place finish,

some a bit too uncomfortable to describe here, but trust me—there are a lot of them.

Here’s a little story that I promise is true, but I’ll have to bypass a name for obvious reasons. About a thousand years ago,

shordy after the invention of movable type, I worked in the sports department of the New York Daily News. An expert handicapper had a desk in the corner and his picks ran in the paper every day. He was heading off for a vacation

and asked me for a favor: Would I handicap the races at Aqueduct for the next two weeks? This way there would be no interruption

in the handicapping service, and bettors who relied on his picks wouldn’t go into withdrawal.

Well, I explained, I didn’t think I could pick the winner of the race if it was Secretariat running against a mule. And all

that arcane stuff about mudders (nothing to do with fadders) and maidens (who could also be male) was an alien language, so

suggesting that I pass myself off as an expert seemed as far-fetched as my dream of playing centerfield for the New York Yankees.

“No problem,” he assured me. “I’ll teach you all about it tomorrow,” he said. Which he did.

He went on vacation and I had a merry old time picking the win-place-show results of every race for the next couple of weeks.

When he returned from his fun in the sun, we tabulated the results, and to the amazement of one and all (especially me), I

had amassed a better winning percentage than he had. Then again, Ray Charles throwing darts at the Racing Form would probably have done better than either of us.

Still, he was delighted and grateful that I hadn’t embarrassed him and he decided to thank me by telling me to bet on a certain

horse a few days later. Understand, I was making about $75 a week at the time, frequently skipping even simple meals a couple

of times a week because I couldn’t afford both lunch and a book I just had to have. So I bet two bucks on the horse he told me about, and sure enough, I won about eight dollars and

was feeling pretty good about the whole thing. When he approached me the next day, beaming, he asked how much I’d won, and

I told him. He practically threw me out the window. “I give you a winner,” he shouted, “and you bet a lousy two bucks?” Well,

I had figured, if I can pick them better than he could, just how much did I want to risk?

He patiently explained that when he gave me a winner, it wasn’t exactly because he had handicapped it. It was a sure thing. So he told me he” d give me another, but this time

I should put down a real bet. A week or so later, he gave me another horse. I scraped together what I could and bet twenty

dollars this time. I won nearly ninety dollars (more than a week’s pay!) and felt like John D. Rockefeller (or Scrooge McDuck,

to make a literary reference).

The next day, we replayed the same scene. He was again outraged at my gutlessness and told me so. After calling me lots of

not very nice names, most of which described in colorful and comprehensive detail my lack of brains as well as heart, he told

me he’d give me one more, but then that was it. By now I was getting the hang of it, so I borrowed $200 and handed it over

to my favorite bookie and advised him to lay it off (pass the bet along to another bookie) since this was a sure thing and

I didn’t want to see him lose all the money that I was going to rake in. He told me he’d risk it. Naturally, and you saw this

coming, my horse came in second and I lost everything I’d previously won and a whole lot more. Next day he shrugged and said

you can’t win ’em all.

This scenario taught me several important life lessons. One is that gambling is really a lot of fun, but you have to be a

billionaire or an idiot to do it regularly. The other is that not everything in the world is exactly as it seems, including—and,

perhaps, especially—the integrity of the racetrack.

As a result, this revelation made it evident that racetracks and the people who inhabit that world—most of whom, I’m absolutely

certain, are utterly fair, honest and aboveboard (which is my moment of political correctness for the month)—are the perfect

background for stories of lying, stealing, cheating and any other crime you can conjure.

Here, then, is the field for Murder at the Racetrack—that rare field in which everyone is a winner.

Lawrence Block has received the two greatest honors that the mystery world can bestow: the Grand Master Award from the Mystery

Writers of America and the Diamond Dagger from the (British) Crime Writers’ Association, both for lifetime achievement.

Ken Bruen’s twenty novels are among the darkest in the history of crime fiction. He has been nominated for an Edgar and won

the Shamus award from the Private Eye Writers of America for The Guards, which introduced his Galway-based P.I., Jack Taylor.

Jan Burke won the Edgar for Best Novel in 2000 for Bones, an Irene Kelly novel. She is the founder of the Crime Lab Project, which aims to give greater support for forensic science

in America. She has served on the National Board of Directors of MWA and was the president of the Southern California chapter.

Lorenzo Carcaterra is the author of six books including the controversial Sleepers, which became a New York Times number one bestseller in hardcover and paperback, as well as a major motion picture starring Brad Pitt, Robert De Niro, Kevin

Bacon and Minnie Driver. He is the producer and writer of NBC’s Law and Order.

Max Allan Collins is the author of more than thirty novels, many featuring Nate Heller, all of whose adventures feature real-life

people and some element of actual history. He has made films with Patty McCormack and Mickey Spillane, and wrote the Dick Tracy comic strip for many years.

Thomas H. Cook has been nominated for Edgars five times in three different categories (True Crime, Paperback Original and

Best Novel), winning the Best Novel of the Year award in 1997 for The Chatham School Affair. Several of his novels have been filmed in Japan.

Pat Jordan is the author of more than a thousand stories and articles for such publications as The New Yorker, GQ, The New York Times Magazine, Playboy and Harper’s. He has also written eleven books, one of which, A False Spring, was hailed by Time as one of “the best and truest books about baseball.”

H.R.F. Keating is one of the Grand Old Men of mystery fiction. As one of Britain’s leading critics for more than half a century

and the author of more than fifty books, he was given the Diamond Dagger by the (British) Crime Writers’ Association in 1996

for lifetime achievement.

John Lescroart is the author of sixteen crime novels, the last thirteen featuring Dismas Hardy (beginning with Dead Irish in 1989), which have become regulars on the bestseller lists. Hardy is named for Saint Dismas, who is the patron saint of

thieves and criminals.

Michael Malone has written three mystery novels featuring the wealthy Justin Savile V and his boss, Police Chief Cuddy R.

Mangum, plus the New York Times bestselling The Killing Club, based on the daytime drama series One Life to hive, of which he was the head writer. He won an Edgar for Best Short Story, “Red Clay,” in 1997.

Michele Martinez, like Melanie Vargas, the chief protagonist of her novel Most Wanted (the first of a series), was a federal prosecutor in New York City, serving as Assistant United States Attorney in the Eastern

District, home to the biggest and richest drug gangs in America.

Joyce Carol Oates, a winner of the National Book Award as well as five other nominations, is the author of such best sellers

as We Were the Mulvaneys and Blonde. Arguably the greatest living writer in the world, she is the author of nearly a hundred books, including novels, short story

collections, poetry, criticism, children’s literature and so forth.

Julie Smith has written twenty mystery novels, including five about a San Francisco lawyer, Rebecca Schwartz, who made her

debut in Death Turns a Trick, and nine about Skip Langdon, a female New Orleans cop who was the heroine of the 1991 Edgar-winning New Orleans Mourning.

Scott Wolven has had stories selected for Best American Mystery Stories of the Year for four consecutive years—more appearances than any writer aside from Joyce Carol Oates. His first book, the short story

collection Controlled Burn, was published in 2004 by Scribner.

Now we’re at the post and the bugler is raising the horn to his lips, so get ready for a great ride—and some terrifying moments

as Murder at the Racetrack awaits.

—Otto Penzler

New York, July 2005

Lawrence Block

So who do you like in the third?”

Keller had to hear the question a second time before he realized it was meant for him. He turned, and a little guy in a Mets

warm-up jacket was standing there, a querulous expression on his lumpy face.

Who did he like in the third? He hadn’t been paying any attention, and was stuck for a response. This didn’t seem to bother

the guy, who answered the question himself.

“The Two horse is odds-on, so you can’t make any money betting on him. And the Five horse might have an outside chance, but

he never finished well on turf. The Three, he’s okay at five furlongs, but at this distance? So I got to say I agree with

you.”

Keller hadn’t said a word. What was there to agree with?

“You’re like me,” the fellow went on. “Not like one of these degenerates, has to bet every race, can’t go five minutes without

some action. Me, sometimes I’ll come here, spend the whole day, not put two dollars down the whole time. I just like to breathe

some fresh air and watch those babies run.”

Keller, who hadn’t intended to say anything, couldn’t help himself. He said, “Fresh air?”

“Since they gave the smokers a room of their own,” the little man said, “it’s not so bad in here. Excuse me, I see somebody

I oughta say hello to.”

He walked off, and the next time Keller noticed him the guy was at the ticket window, placing a bet. Fresh air, Keller thought.

Watch those babies run. It sounded good, until you took note of the fact that those babies were out at Belmont, running around

a track in the open air, while Keller and the little man and sixty or eighty other people were jammed into a midtown storefront,

watching the whole thing on television.

Keller, holding a copy of the Racing Form, looked warily around the OTB parlor. It was on Lexington at Forty-fifth Street, just up from Grand Central, and not much

more than a five-minute walk from his First Avenue apartment, but this was his first visit. In fact, as far as he could tell,

it was the first time he had ever noticed the place. He must have walked past it hundreds if not thousands of times over the

years, but he’d somehow never registered it, which showed the extent of his interest in off-track betting.

Or on-track betting, or any betting at all. Keller had been to the track three times in his entire life. The first time he’d

placed a couple of small bets—two dollars here, five dollars there. His horses had run out of the money, and he’d felt stupid.

The other times he hadn’t even put a bet down.

He’d been to gambling casinos on several occasions, generally work related, and he’d never felt comfortable there. It was

clear that a lot of people found the atmosphere exciting, but as far as Keller was concerned it was just sensory overload.

All that noise, all those flashing lights, all those people chasing all that money. Keller, feeding a slot machine or playing

a hand of blackjack to fit in, just wanted to go to his room and lie down.

Well, he thought, people were different. A lot of them clearly got something out of gambling. What some of them got, to be

sure, was the attention of Keller or somebody like him. They’d lost money they couldn’t pay, or stolen money to gamble with,

or had found some other way to make somebody seriously unhappy with them. Enter Keller, and, sooner rather than later, exit

the gambler.

For most gamblers, though, it was a hobby, a harmless pastime. And, just because Keller couldn’t figure out what they got

out of it, that didn’t mean there was nothing there. Keller, looking around the OTB parlor at all those woulda-coulda-shoulda

faces, knew there was nothing feigned about their enthusiasm. They were really into it, whatever it was.

And, he thought, who was he to say their enthusiasm was misplaced? One man’s meat, after all, was another man’s pots-son. These fellows, all wrapped up in Racing Form gibberish, would be hard put to make sense out of his Scott catalog. If they caught a glimpse of Keller, hunched over one

of his stamp albums, a magnifying glass in one hand and a pair of tongs in the other, they’d most likely figure he was out

of his mind. Why play with little bits of perforated paper when you could bet money on horses?

“They’re off!”

And so they were. Keller looked at the wall-mounted television screen and watched those babies run.

• • •

It started with stamps.

He collected worldwide, from the first postage stamp, Great Britain’s Penny Black and Two-Penny Blue of 1840, up to shordy

after the end of World War II. (Just when he stopped depended upon the country. He collected most countries through 1949,

but his British Empire issues stopped at 1952, with the death of George VI. The most recent stamp in his collection was over

fifty years old.)

When you collected the whole world, your albums held spaces for many more stamps than you would ever be able to acquire. Keller

knew he would never completely fill any of his albums, and he found this not frustrating but comforting. No matter how long

he lived or how much money he got, he would always have more stamps to look for. You tried to fill in the spaces, of course—that

was the point—but it was the trying that brought you pleasure, not the accomplishment.

Consequently, he never absolutely had to have any particular stamp. He shopped carefully, and he chose the stamps he liked,

and he didn’t spend more than he could afford. He’d saved money over the years, he’d even reached a point where he’d been

thinking about retiring, but when he got back into stamp collecting, his hobby gradually ate up his retirement fund—which,

all things considered, was fine with him. Why would he want to retire? If he retired, he’d have to stop buying stamps.

As it was, he was in a perfect position. He was never desperate for money, but he could always find a use for it. If Dot came

up with a whole string of jobs for him, he wound up putting a big chunk of the proceeds into his stamp collection. If business

slowed down, no problem—he’d make small purchases from the dealers who shipped him stamps on approval, send some small checks

to others who mailed him their monthly lists, but hold off on anything substantial until business picked up.

It worked fine. Until the Bulger & Calthorpe auction catalog came along and complicated everything.

Bulger & Calthorpe were stamp auctioneers based in Omaha. They advertised regularly in Linn’s and the other stamp publications, and traveled extensively to examine collectors’ holdings. Three or four times a year they

would rent a hotel suite in downtown Omaha and hold an auction, and for a few years now Keller had been receiving their well-illustrated

catalogs. Their catalog featured an extensive collection of France and French colonies, and Keller leafed through it on the

off-chance that he might find himself in Omaha around that time. He was thinking of something else when he hit the first page

of color photographs, and whatever it was he forgot it forever.

Martinique #2. And, right next to it, Martinique #17.

• • •

On the screen, the Two horse led wire to wire, winning by four and a half lengths. “Look at that,” the little man said, once

again at Keller’s elbow. “What did I tell you? Pays three-fucking-forty for a two-dollar ticket. Where’s the sense in that?”

“Did you bet him?”

“I didn’t bet on him,” the man said, “and I didn’t bet against him. What I had, I had the Eight horse to place, which is nothing

but a case of getting greedy, because look what he did, will you? He came in third, right behind the Five horse, so if I bet

him to show, or if I semi-wheeled the Trifecta, playing a Two-Five-Eight and a Two-Eight-Five…”

Woulda-coulda-shoulda, thought Keller.

• • •

He’d spend half an hour with the Bulger & Calthorpe catalog, reading the descriptions of the two Martinique lots, seeing what

else was on offer, and returning more than once for a further look at Martinique #2 and Martinique #17. He interrupted himself

to check the balance in his bank account, frowned, pulled out the album that ran from Leeward Islands to Netherlands, opened

it to Martinique, and looked first at the couple hundred stamps he had and then at the two empty spaces, spaces designed to

hold—what else?—Martinique #2 and Martinique #17.

He closed the album but didn’t put it away, not yet, and he picked up the phone and called Dot.

“I was wondering,” he said, “if anything came in.”

“Like what, Keller?”

“like work,” he said.

“Was your phone off the hook?”

“No,” he said. “Did you try to call me?”

“If I had,” she said, “I’d have reached you, since your phone wasn’t off the hook. And if a job came in I’d have called, the

way I always do. But instead you called me.”

“Right.”

“Which leads me to wonder why.”

“I could use the work,” he said. “That’s all.”

“You worked when? A month ago?”

“Closer to two.”

“You took a little trip, went like clockwork, smooth as silk. Client paid me and I paid you, and if that’s not silken clockwork

I don’t know what is. Say, is there a new woman in the picture, Keller? Are you spending serious money on earrings again?”

“Nothing like that.”

“Then why would you… Keller, it’s stamps, isn’t it?”

“I could use a few dollars,” he said. “That’s all.“

” So you decided to be proactive and call me. Well, I’d be proactive myself, but who am I gonna call? We can’t go looking

for our kind of work, Keller. It has to come to us.”

“I know that.”

“We ran an ad once, remember? And remember how it worked out?” He remembered, and made a face. “So we’ll wait,” she said,

“until something comes along. You want to help it a little on a metaphysical level, try thinking proactive thoughts.”

• • •

There was a horse in the fourth race named Going Postal. That didn’t have anything to do with stamps, Keller knew, but was

a reference to the propensity of disgruntled postal employees to exercise their Second Amendment rights by bringing a gun

to work, often with dramatic results. Still, the name was guaranteed to catch the eye of a philatelist.

“What about the Six horse? ” Keller asked the little man, who consulted in turn the Racing Form and the tote board on the television.

“Finished in the money three times in his last five starts,” he reported, “but now he’s moving up in class. Likes to come

from behind, and there’s early speed here, because the Two horse and the Five horse both like to get out in front. ” There

was more that Keller couldn’t follow, and then the man said, “Morning line had him at twelve-to-one, and he’s up to eighteen-to-one

now, so the good news is he’ll pay a nice price, but the bad news is nobody thinks he’s got much of a chance.”

Keller got in line. When it was his turn, he bet two dollars on Going Postal to win.

• • •

Keller didn’t know much about Martinique beyond the fact that it was a French possession in the West Indies, and he knew the

postal authorities had stopped issuing special stamps for the place a while ago. It was now officially a department of France,

and used regular French stamps. The French did that to avoid being called colonialists. By designating Martinique a part of

France, the same as Normandy or Provence, they obscured the fact that the island was full of black people who worked in the

fields, fields that were owned by white people who lived in Paris.

Keller had never been to Martinique—or to France, as far as that went—and had no special interest in the place. It was a funny

thing about stamps; you didn’t need to be interested in a country to be interested in the country’s stamps. And he couldn’t

say what was so special about the stamps of Martinique, except that one way or another he had accumulated quite a few of them,

and that made him seek out more, and now, remarkably, he had all but two.

The two he lacked were among the colony’s first issues, created by surcharging stamps originally printed for general use in

France’s overseas empire. The first, #2 in the Scott catalog, was a twenty-centime stamp surcharged “MARTINIQUE” and “5 c”

in black. The second, #17, was similar: “MARTINIQUE / 15c” on a four-centime stamp.

According to the catalog, #17 was worth $7,500 mint, $7,000 used. #2 was listed at $11,000, mint or used. The listings were

in italics, which was the catalog’s way of indicating that the value was difficult to determine precisely.

Keller bought most of his stamps at around half the Scott valuation. Stamps with defects went much cheaper, and stamps that

were particularly fresh and well centered could command a premium. With a true rarity, however, at a well-publicized auction,

it was very hard to guess what price might be realized. Bulger & Calthorpe described #2—it was lot #2144 in their sales catalog—as

“mint with part OG, F-VF, the nicest specimen we’ve seen of this genuine rarity.” The description of #17—lot #215 3—was almost

as glowing. Both stamps were accompanied by Philatelic Foundation certificates attesting that they were indeed what they purported

to be. The auctioneers estimated that #2 would bring $15,000, and pegged the other at $10,000.

But those were just estimates. They might wind up selling for quite a bit less, or a good deal more.

Keller wanted them.

• • •

Going Postal got off to a slow start, but Keller knew that was to be expected. The horse liked to come from behind. And in

fact he did rally, and was running third at one point, fading in the stretch and finishing seventh in a field of nine. As

the little man had predicted, the Two and Five horses had both gone out in front, and had both been overtaken, though not

by Going Postal. The winner, a dappled horse named Doggen Katz, paid $19.20.

“Son of a bitch,” the little man said. “I almost had him. The only thing I did wrong was decide to bet on a different horse.”

• • •

What he needed, Keller decided, was fifty thousand dollars. That way he could go as high as twenty-five for #2 and fifteen

for #17 and, after buyer’s commission, still have a few dollars left for expenses and other stamps.

Was he out of his mind? How could a little piece of perforated paper less than an inch square be worth $25,000? How could

two of them be worth a man’s life?

He thought about it and decided it was just a question of degree. Unless you planned to use it to mail a letter, any expenditure

for a stamp was basically irrational. If you could swallow a gnat, why gag at a camel? A hobby, he suspected, was irrational

by definition. As long as you kept it in proportion, you were all right.

And he was managing that. He could, if he wanted, mortgage his apartment. Bankers would stand in line to lend him fifty grand,

since the apartment was worth ten times that figure. They wouldn’t ask him what he wanted the money for, either, and he’d

be free to spend every dime of it on the two Martinique stamps.

He didn’t consider it, not for a moment. It would be nuts, and he knew it. But what he did with a windfall was something else,

and it didn’t matter, anyway, because there wasn’t going to be any windfall. You didn’t need a weatherman, he thought, to

note that the wind was not blowing. There was no wind, and there would be no windfall, and someone else could mount the Martinique

overprints in his album. It was a shame, but—

The phone rang.

Dot said, “Keller, I just made a pitcher of iced tea. Why don’t you come up here and help me drink it?”

• • •

In the fifth race, there was a horse named Happy Trigger and another named Hit the Boss. If Going Postal had resonated with

his hobby, these seemed to suggest his profession. He mentioned them to the little fellow. “I sort of like these two,” he

said. “But I don’t know which one I like better.”

“Wheel them,” the man said, and explained that Keller should buy two Exacta tickets, Four-Seven and Seven-Four. That way Keller

would only collect if the two horses finished first and second. But, since the tote board indicated long odds on each of them,

the potential payoff was a big one.

“What would I have to bet?” Keller asked him. “Four dollars? Because I’ve only been betting two dollars a race.”

“You want to keep it to two dollars,” his friend said, “just bet it one way. Thing is, how are you going to feel if you bet

the Four-Seven and they finish Seven-Four?”

• • •

“It’s right up your alley,” Dot told him. “Comes through another broker, so there’s a good solid firewall between us and the

client. And the broker’s reliable, and if the client was a corporate bond he’d be rated triple-A.”

“What’s the catch?”

“Keller,” she said, “what makes you think there’s a catch?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “But there is, isn’t there?”

She frowned. “The only catch,” she said, “if you want to call it that, is there might not be a job at all.”

“I’d call that a catch.”

“I suppose.”

“If there’s no job,” he said, “why did the client call the broker, and why did the broker call you, and what am I doing out

here?”

Dot pursed her lips, sighed. “There’s this horse,” she said.

• • •

The fifth race was reasonably exciting. Bunk Bed Betty, a big

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...