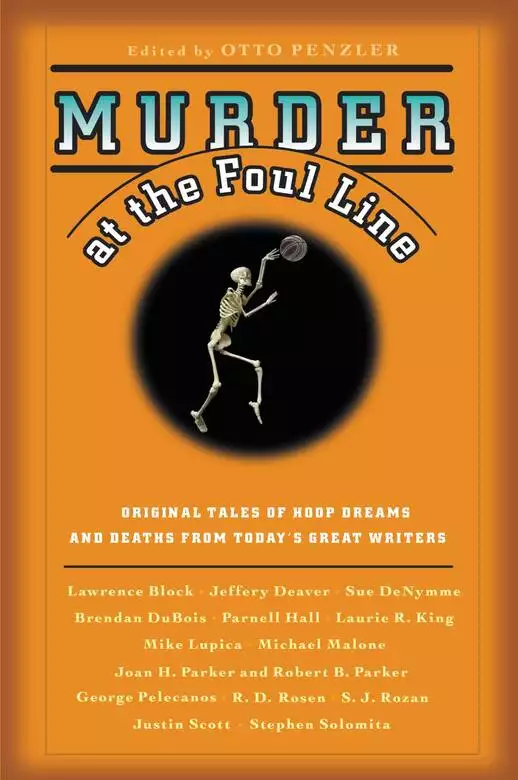

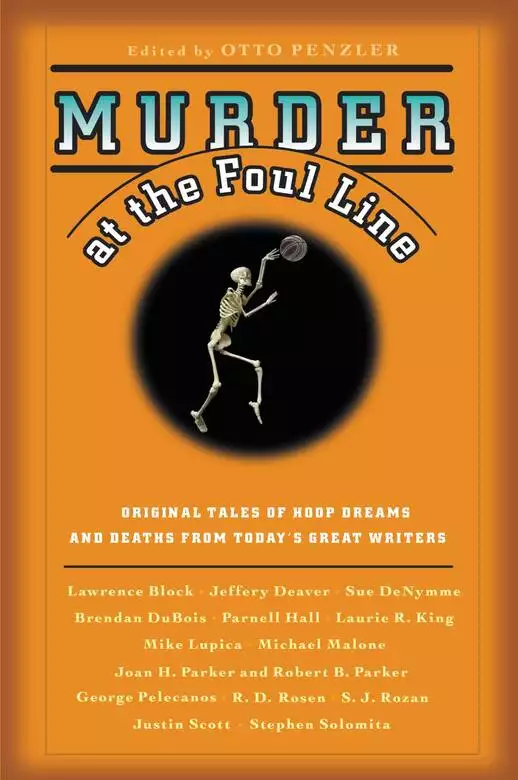

Murder at the Foul Line

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

When murder, mystery and suspense are thrown onto the court, basketball can become a deadly game. Amazing athletic displays, astronomical salaries, outrageous bets, rich and famous owners, coaches, managers and groupies...all are part of the game of hoops and appear in this collection, the fifth in the popular series by noted mystery anthologist Otto Penzler. With contributions from the finest names in crime and suspense writing today, including Jeffery Deaver, Brendan DuBois, Lawrence Block, Laurie R. King and more...this latest collection is sure to please hoops fans and mystery lovers both.

Release date: October 14, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder at the Foul Line

Otto Penzler

Basketball was a little different when I was growing up, which is just before James Naismith reputedly invented the game in

1891.

First, most of the players were white. I don’t know if they could jump, but I do know they didn’t jump. Dunking was something you did with a doughnut and a cup of coffee. There was such a thing as a two-handed set shot.

I’m not making this up. Hook shots were common, and soon some of the better players developed a jump shot. Foul shots were

frequently taken underhanded, with two hands guiding the ball toward the hoop. Eventually, to help speed the game up, the

twenty-four-second clock was invented.

Second, players actually played by the rules, mainly because the referees called fouls and other violations. Traveling, for

example, was called if a player carried the ball for two steps. Today it’s called only if he carries the ball to another city.

Basketball was described accurately back in the Dark Ages as a noncontact sport. If you bumped into a player, you were called

for a foul. Today the foul is called only if you hit someone repeatedly, generally with a blunt instrument.

Also, players seemed tall but human. Today the guys who used to be the “big” forward (now known as the power forward) are

the speedy little guys who bring the ball up the court. The big guys seem descended from another planet.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not some old fogey who thinks players were better when I was a kid. I’m an old fogey who thinks basketball

players during the past quarter century or so are the best all-around athletes in the world. They just don’t play the same

game. I’m not sure when it went from being a team sport to being a game played by five individuals to a side, but it was probably

when ESPN’s SportsCenter started to show highlights every night and 95 percent of them were dunks (just as most baseball highlights on that show are

home runs, and there’s nothing more boring than watching one long fly ball after another landing in the seats).

But perhaps the biggest difference in the game is the level of criminal activity. One of the big crime stories of the 1950s

was when some Manhattan College, CCNY, and Long Island University players conspired to fix games so that certain gamblers

could make a killing. The scandal rocked the sport for years, and those teams, then national powers, never recovered.

Today, of course, that would be looked upon as kid stuff. Now we’re really talking. Stars are commonly arrested for drug abuse,

drunk driving, wife (and girlfriend) battering, barroom brawling, rape, and so many other acts of violence and criminality

that it is difficult to keep track.

There was a time when I thought Kermit Washington’s brutal punch of an innocent and unsuspecting Rudy Tom-janovich, caving

in his face, fracturing his skull, breaking his jaw and nose, and causing a potentially lethal spinal fluid drip from his

brain, was the most disgusting thing I’d ever seen on a

basketball court, but that was before Ron Artest and fellow thugs on the Indiana Pacers brawled with fans in Detroit. Now,

I’ll quickly concede that some guy who throws a cup full of beer into the face of a six-foot-eight-inch tower of muscle is

so stupid that he probably deserves a good whipping, but still…

Even this pales when compared with Latrell Sprewell’s attempted murder of his coach. Not merely in the heat of the moment,

mind you. He grabbed P. J. Carlesimo, put his big hands around his throat, and choked him until he was pulled away. He left,

came back about twenty minutes later, and did it again! (Well, Sprewell explained later, it’s not like he couldn’t breathe at all.) Because he’s a star athlete, he didn’t do a single day in jail. Instead, he got traded to the New York Knicks and became

a crowd favorite. When he left the team as a free agent, he spurned a $29-million offer, explaining that it wasn’t enough,

that he had to feed his family.

Jayson Williams, a great basketball player and a charming man, was not convicted of killing his chauffeur.

In a never-ending headline story, Kobe Bryant was arrested for rape but admits only to being stupid and an adulterer. Allen

Iverson, who has all the charm of a Mexican snuff film, was arrested with illegal weapons—again. Charles Barkley cold-cocked

a pencil-thin opponent in the Olympics for no discernible reason. There was a perfectly good reason for him to throw someone through a barroom window. He’d been hassled by the idiot. When asked if

he had any regrets about the incident, Barkley said yes. He was sorry they hadn’t been on a higher floor.

The notion, then, of mixing basketball and crime in this collection seems predictable—a natural combination, like ham

and eggs, Laurel and Hardy, yin and yang. Or, to put it more darkly, it’s a predictably unnatural combination, like Michael

Jackson and little boys, S&M, Paris Hilton and farm animals, and the team of buffoons (sorry, self-described “idiots”) known

as the 2004 World Champion Boston Red Sox.

It would be difficult to think that a group of fiction writers, people who make up stories, could find a way to write about

crime and criminals in a way that surpasses the real-life adventures we can all read about in the tabloids, but the assembled

team of top-notch mystery writers has done just that. This Dream Team of outstanding authors has put together a game plan

that will keep you at the edge of your seat right to the last second. Here is the lineup of superstars:

Lawrence Block has received the highest honor bestowed by the Mystery Writers of America, the Grand Master Award for lifetime

achievement, and received the equivalent prize, the Diamond Dagger, from the Crime Writers’ Association of Great Britain.

He has produced more than sixty novels, mainly about such series characters as the tough alcoholic private eye, Matt Scudder;

his comedic bookseller/burglar, Bernie Rhodenbarr; and the amoral hit man who appears in this volume, Keller.

Jeffery Deaver is the author of twenty novels, many featuring Lincoln Rhyme, including The Bone Collector, which was filmed starring Denzel Washington. Deaver has been nominated for four Edgar Allan Poe Awards and an Anthony and

is the three-time recipient of the Ellery Queen Reader’s Award for Best Short Story of the Year. Garden of Beasts won the 2004 Ian Fleming Steel Dagger Award by the Crime Writers’ Association of Great Britain for the best thriller in the

vein of James Bond.

Sue DeNymme has a rich bloodline of storytellers, embellishers, and exaggerators, including fishermen, pirates, and royalty.

She has traveled extensively, studying language and culture, and has earned degrees from several prestigious universities.

When she began writing, she immediately won a poetry prize. Now that she has decided to write the tallest possible tales,

she chose mystery fiction for her career. In fact, she is in the process of writing a crime novel and cannot wait to read

it.

Brendan DuBois is the author of seven novels, one of which, Resurrection Day, is planned as a major motion picture. He has produced numerous short stories, three of which have been nominated for Edgar

Allan Poe Awards and two of which have won Shamus Awards. His story “The Dark Snow” was selected for Best American Mystery Stories of the Century, edited by Tony Hillerman.

Parnell Hall is the author of the critically acclaimed Stanley Hastings series about an inept and cowardly private eye, and

the Puzzle Lady novels that involve crossword puzzles as clues, voted the Best New Discovery by members of the Mystery Guild.

He has been nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe Award by the Mystery Writers of America and the Shamus Award by the Private Eye

Writers of America.

Laurie R. King writes stand-alone thrillers, a series about San Francisco homicide inspector Kate Martinelli and, most notably,

a series about Sherlock Holmes and his wife, Mary Russell. Her first novel, A Grave Talent, won the Edgar and the John Creasey Awards from the (British) Crime Writers’ Association. With Child was nominated for an Edgar.

Mike Lupica is one of the best-known and most accomplished sportswriters in America, a regular on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters, as well as the author of fifteen books of fiction, non-fiction,

juvenile and mystery fiction. His first mystery, Dead Air, was nominated for an Edgar and was later filmed for CBS as Money, Power and Murder. His most recent novel, Too Far, was a national best-seller.

Michael Malone has written three mysteries, Uncivil Seasons, Time’s Witness, and First Lady, as well as several mainstream novels, notably such modern classics as Dingley Falls, Handling Sin, and Foolscap. He was the head writer for various daytime drama series, including One Life to Live. His short story “Red Clay” won the Edgar and was selected for Best American Mystery Stories of the Century.

Joan H. Parker is the coauthor, with her husband, Robert B. Parker, of Three Weeks in Spring, the moving story of her battle with cancer, and A Year at the Races, a pictorial journal of their adventures with horse racing. She and her husband also collaborated on several scripts for

Spenser, the television series based on the Boston P.I.

Robert B. Parker, acclaimed as the contemporary private eye writer in the pantheon of Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald,

won an Edgar for Promised Land, the fourth in the series of instant classics involving Spenser, the tough, wisecracking Boston P.I. who was the basis for

a network television series in the 1990s. Parker was recently named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America.

George Pelecanos, one of the most critically acclaimed crime writers in America, is the author of a dozen novels with several

different series characters, most notably Nick Stefanos and the team of Derek Strange and Terry Quinn. Hell to Pay won the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and The Big Blowdown won the International Crime Novel of the Year Award in

France, Germany, and Japan. He is currently a writer and producer of the HBO series The Wire.

R. D. Rosen has written for Saturday Night Live and several CBS news shows, but he claims that his novels about Harvey Blissberg, a professional baseball player turned private

eye, are closest to his heart. His first book, Strike Three, You’re Dead, won the Edgar in 1984 and was recently named “one of the hundred favorite mysteries of the century” by the Independent Booksellers

Association.

S. J. Rozan is one of the most honored mystery writers of recent years, winning two Edgars (for Best Short Story and Best

Novel), as well as a Shamus, Macavity, Nero, and Anthony. Her series characters are Lydia Chin, a young American-born Chinese

private eye whose cases originate mainly in New York’s Chinese community, and Chin’s partner, Bill Smith, an older, more experienced

sleuth who lives above a bar in Tribeca.

Justin Scott is the author of more than twenty novels, including such huge international best-sellers as The Shipkiller, The Widow of Desire, and A Pride of Royals. His humorous mystery Many Happy Returns was nominated for an Edgar in 1974. His most recent series of novels, recounting the adventures of Benjamin Abbott, a real

estate agent in the charming Connecticut town of Newbury, includes HardScape, StoneDust, and Frostline.

Stephen Solomita has received an extraordinary amount of critical acclaim, being compared to Elmore Leonard and Tom Wolfe

(by the New York Times), to Joseph Wambaugh and William J. Caunitz (by the Associated Press), and to John Grisham (Kirkus Reviews). He is the author of nearly twenty books under his own name, many about Stanley Moodrow, a tough New York City cop, and

under the pseudonym David Cray.

So let the games begin. Oh, one more thing. While it is generally accepted that James Naismith invented the game of basketball

in 1891 by cutting out the bottom of a peach basket and nailing it to a wall, in fact a very similar game had been played

hundreds of years earlier. The object was to put a rubber ball through a ring. The stakes were pretty high, as it was possible

that the captain of the losing team would be beheaded. Maybe we shouldn’t let this become common knowledge. Some of the thugs

in the NBA might think it’s a good idea to reinstate the custom.

—Otto PenzlerJanuary 2005, New York

Lawrence Block

Keller, his hands in his pockets, watched a dark-skinned black man with his shirt off drive for the basket. His shaved head

gleamed, and the muscles of his upper back, the traps and lats, bulged as if steroidally enhanced. Another man, wearing a

T-shirt but otherwise of the same shade and physique, leapt to block the shot, and the two bodies met in midair. It was a

little like ballet, Keller thought, and a little like combat, and the ball kissed off the backboard and dropped through the

hoop.

There was no net, just a bare hoop. The playground was at the corner of Sixth Avenue and West Third Street, in Greenwich Village,

and Keller was one of a handful of spectators standing outside the high chain-link fence, watching idly as ten men, half wearing

T-shirts, half bare-chested, played a fiercely competitive game of half-court basketball.

If this were a game at the Garden, the last play would have sent someone to the free-throw line. But there was no ref here

to call fouls, and order was maintained in a simpler fashion: Anyone who fouled too frequently was thrown out of the

game. It was, Keller felt, an interesting libertarian solution, and he thought it might be worth a try outside the basketball

court, but had a feeling it would be tough to make it work.

Keller watched a few more plays, feeling his spirits sink as he did, yet finding it oddly difficult to tear himself away.

He’d had a tooth drilled and filled a few blocks away, by a dentist who had himself played varsity basketball years ago at

the University of Kentucky, and had been walking around waiting for the Novocain to wear off so he could grab some lunch,

and the basketball game had caught his eye, and here he was. Watching, and being brought down in the process, because basketball

always depressed him.

His mouth wasn’t numb anymore. He crossed the street, walked two blocks east, turned right on Sullivan Street, left on Bleecker.

He considered and rejected restaurants as he walked, knowing he wanted something spicy. If basketball depressed him, highly

seasoned food put him right again. He thought it odd, didn’t understand it, but knew it worked.

The restaurant he found was Indian, and Keller made sure the waiter got the message. “You tone things down for Westerners,”

he told the man. “I only look like an American of European ancestry. Inside, I am a man from Sri Lanka.”

“You want spicy,” the waiter said.

“I want very spicy,” Keller said. “And then some.”

The little man beamed. “You wish to sweat.”

“I wish to suffer.”

“Leave it to me,” the little man said.

The meal was almost too hot to eat. It was nominally a lamb curry, but its ingredients might have been anything. Lamb, beef,

dog, duck. Tofu, shoe leather, balsawood. Papier-mâché? Plaster of paris? The searing heat of the cayenne obscured everything

else. Keller, forcing himself to finish every bite, loved and hated every minute of it. By the time he was done he was drenched

in perspiration and felt as if he’d just gone ten rounds with a worthy opponent. He felt, too, a sense of accomplishment and

an abiding sense of peace with the world.

Something made him call home to check his answering machine. Two hours later he was on the front porch of the big old house

on Taunton Place, sipping a glass of iced tea. Three days after that he was in Indiana.

At the Avis desk at Indy International, Keller turned in the Chevy he’d driven from New York. At the Hertz counter, he picked

up the keys to the Ford he’d reserved. He carried his bag to the car, left it in short-term parking, and went back into the

airport, remembering to take his bag with him. There was a fellow waiting at baggage claim, wearing the green and gold John

Deere cap they’d said he’d be wearing.

“Oh, there you are,” the fellow said when Keller approached him. “The bags are just starting to come down.”

Keller brandished his carry-on, said he hadn’t checked anything.

“Then I guess you didn’t bring a nail clipper,” the man said, “or a Swiss Army knife. Never mind a bazooka.”

Keller had a Swiss Army knife in his carry-on and a nail clipper in his pocket, attached to his key ring. Since he hadn’t

flown anywhere, he’d had no problem. As for the other, well, he had never minded a bazooka in his life, and saw no reason

to start now.

“Now let’s get you squared away,” the man said. He was around forty, and lean, except for an incongruous potbelly, as if he’d

swallowed a small watermelon. “Quick orientation, drive you around, show you where he lives. We’ll take my car, and when we’re

done, you can drop me off and keep it.”

The airport was at the southwest corner of Indianapolis, and the man (who’d flipped the John Deere cap into the back-seat

of his Hyundai squareback, alongside Keller’s carry-on) drove to Carmel, an upscale suburb north of the I-465 beltway. He

made a few efforts at conversation, which Keller let wither on the vine, whereupon he gave up and switched on the radio. He

kept it tuned to an all-talk station, and right now two opinionated fellows were arguing about the outsourcing of jobs.

Keller thought about turning it off. You’re a hit man, brought in at great expense from out of town, and some gofer picks

you up and plays the radio, and you turn it off, what’s he gonna do? Be impressed and a little intimidated, he thought, but

decided it wasn’t worth the trouble.

The driver killed the radio himself when they left the interstate and drove through the treelined streets of Carmel. Keller

paid close attention now, noting street names and landmarks and taking a good look at the house that was pointed out to him.

It was a Dutch Colonial with a mansard roof, he noted, and that tugged at his memory until he remembered a real estate agent

in Roseburg, Oregon, who’d shown him through a similar house years ago. Keller had wanted to buy it, to move there. For a

few days, anyway, until he came to his senses.

When they were done, the man asked him if there was anything else he wanted to see, and Keller said there wasn’t. “Then I’ll

drive you to my house,” the man said, “and you can drop me off.”

Keller shook his head. “Drop me at the airport,” he said.

“Oh, Jesus,” the man said. “Is something wrong? Did I say the wrong thing?”

Keller looked at him.

“’Cause if you’re backing out, I’m gonna get blamed for it. They’ll have a goddamn fit. Is it the location? Because, you know,

it doesn’t have to be at his house. It could be anywhere.”

Oh. Keller explained that he didn’t want to use the Hyundai, that he’d pick up a car at the airport. He preferred it that

way, he said.

Driving back to the airport, the man obviously wanted to ask why Keller wanted his own car, and just as obviously was afraid

to say a word. Nor did he play the radio. The silence was a heavy one, but that was okay with Keller.

When they got there, the fellow said he supposed Keller wanted to rent a car. Keller shook his head and directed him to the

lot where he’d already stowed the Ford. “Keep going,” he said. “Maybe that one… no, that’s the one I want. Stop here.”

“What are you gonna do?”

“Borrow a car,” Keller said.

He’d added the key to his key ring, and now he stood alongside the car and made a show of flipping through keys, finally selecting

the one they’d given him. He tried it in the door and, unsurprisingly, it worked. He tried it in the ignition, and it worked

there, too. He switched off the ignition and went back to the Hyundai for his carry-on, where the driver, wide-eyed, asked

him if he was really going to steal that car.

“I’m just borrowing it,” he said.

“But if the owner reports it—”

“I’ll be done with it by then.” He smiled. “Relax. I do this all the time.”

The fellow started to say something, then changed his mind. “Well,” he said instead. “Look, do you want a piece?”

Was the man offering him a woman? Or, God forbid, offering to supply sexual favors personally? Keller frowned and then realized

the piece in question was a gun. Keller, relieved, shook his head and said he had everything he needed in his carry-on. Amazing

the damage you could inflict with a Swiss Army knife and a nail clipper.

“Well,” the man said again. “Well, here’s something.” He reached into his breast pocket and came out with a pair of tickets.

“To the Pacers game,” he said. “They’re playing the Knicks, so I guess you’ll be rooting for your homies, huh? Tonight, eight

sharp. They’re not courtside, but they’re damn good seats. You want, I could dig up somebody to go with you, keep you company.”

Keller said he’d take care of that himself, and the man didn’t seem surprised to hear it.

“He’s a witness,” Dot had said, “but apparently nobody’s thought of sticking him in the Federal Witness Protection Program,

but maybe that’s because the situation’s not federal. Do you have to be involved in a federal case in order to be protected

by the federal government?”

Keller wasn’t sure, and Dot said it didn’t really matter. What mattered was that the witness wasn’t in the program, and wasn’t

hidden at all, and that made it a job for Keller, because the client really didn’t want the witness to stand up and testify.

“Or sit down and testify,” she said, “which is what they usually do, at least on the television programs I watch. The lawyers

stand up, and even walk around some, but the witnesses just sit there.”

“What did he witness, do you happen to know?”

“You know,” she said, “they were pretty vague on that point. The guy I talked to wasn’t a principal. He was more like a booking

agent. I’ve worked with him before, when his clients were O.C. guys.”

“Huh?”

“Organized crime. So he’s connected, but this isn’t O.C., and my sense is it’s not violent.”

“But it’s going to get that way.”

“Well, you’re not going all the way to Indiana to talk sense into him, are you? What he witnessed, I think it was like corporate

shenanigans. What’s the matter?”

“Shenanigans,” he said.

“It’s a perfectly good word. What’s the matter with shenanigans?”

“I just didn’t think anybody said it anymore,” he said. “That’s all.”

“Well, maybe they should. God knows they’ve got occasion to.”

“If it’s corporate fiddle-faddle,” he began, and stopped when she held up a hand.

“Fiddle-faddle? This from a man who has a problem with shenanigans?”

“If it’s that sort of thing,” he said, “then it actually could be federal, couldn’t it?”

“I suppose so.”

“But he’s not in the witness program because they don’t think he’s in danger.”

She nodded. “Stands to reason.”

“So they probably haven’t assigned people to guard him,” he said, “and he’s probably not taking precautions.”

“Probably not.”

“Should be easy.”

“It should,” she agreed. “So why are you disappointed?”

“Disappointed?”

“That’s the vibe I’m getting. Are you picking up on something? Like it’s really going to be a lot more complicated than it

sounds?”

He shook his head. “I think it’s going to be easy,” he said, “and I hope it is, and I’m not picking up any vibe. And I certainly

didn’t mean to sound disappointed, because I don’t feel disappointed. I can use the money, and besides that, I can use the

work. I don’t want to go stale.”

“So there’s no problem.”

“No. As far as your vibe is concerned, well, I spent the morning at the dentist.”

“Say no more. That’s enough to depress anybody.”

“It wasn’t, really. But then I was watching some guys play basketball. The Indian food helped, but the mood lingered.”

“You’re just one big non sequitur, aren’t you, Keller?” She held up a hand. “No, don’t explain. You’ll go to Indianapolis,

you lucky man, and your actions will get to speak for themselves.”

Keller’s motel was a Rodeway Inn at the junction of Inter-states 465 and 69, close enough to Carmel but not too close. He

signed in with a name that matched his credit card and made up a license plate number for the registration card. In his room,

he ran the channels on the TV, then switched off the set. He took a shower, got dressed, turned the TV on, turned it off again.

Then he went to the car and found his way to the Conseco

Fieldhouse, where the Indiana Pacers were playing host to the New York Knicks.

The stadium was in the center of the city, but the signage made it easy to get there. A man in a porkpie hat asked him in

an undertone if he had any extra tickets, and Keller realized that he did. He took a good look at his tickets for the first

time and saw that he had a pair of $96 seats in section 117, wherever that was. He could sell one, but wouldn’t that be awkward

if the man he sold it to sat beside him? He’d probably be a talker, and Keller didn’t want that.

But a moment’s observation clarified the situation. The man in the porkpie hat—who had, Keller noted, a face straight out

of an OTB parlor, a coulda-woulda-shoulda gambler’s face—was doing a little business, buying tickets from people who had too

many, selling them to people who had too few. So he wouldn’t be sitting next to Keller. Someone else would, but it would be

someone he hadn’t met, so it would be easy to keep an intimacy barrier in place.

Keller went up to the man in the hat, showed him one of the tickets. The man said, “Fifty bucks,” and Keller pointed out that

it was a $96 ticket. The man gave him a look, and Keller took the ticket back.

“Jesus,” the man said. “What do you want for it, anyway?”

“Eighty-five,” Keller said, picking the number out of the air.

“That’s crazy.”

“The Pacers and the Knicks? Section 117? I bet I can find somebody who wants it eighty-five dollars’ worth.”

They settled on $75, and Keller pocketed the money and used his other ticket to enter the arena. Then it struck him that he

could have unloaded both tickets and had $150 to show for

it, and gone straight home, spared the ordeal of a basketball game. But he was already through the turnstile when the thought

came to him, and by that point he no longer had a ticket to sell.

He found his seat and sat down to watch the game.

Keller, an only child, was raised by his mother, who he had come to realize in later years was probably mentally ill. He never

suspected this at the time, although he was aware that she was different from other people.

She kept a picture of Keller’s father in a frame in the living room. The photograph showed a young man in a military uniform,

and Keller grew up knowing that his father had been a soldier, a casualty of the war. As a teenager, he’d been employed cleaning

out a stockroom, and one of the boxes of obsolete merchandise he’d hauled out had contained picture frames, half of them containing

the familiar photograph of his putative father.

It occurred to him that he ought to mention this to his mother. On further thought, he decided not to say anything. He went

home and looked at the photo and wondered who his father was. A soldier, he decided, though not this one. Someone passing

through, who’d fathered a son and never knew it.

And died in battle? Well, a l

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...