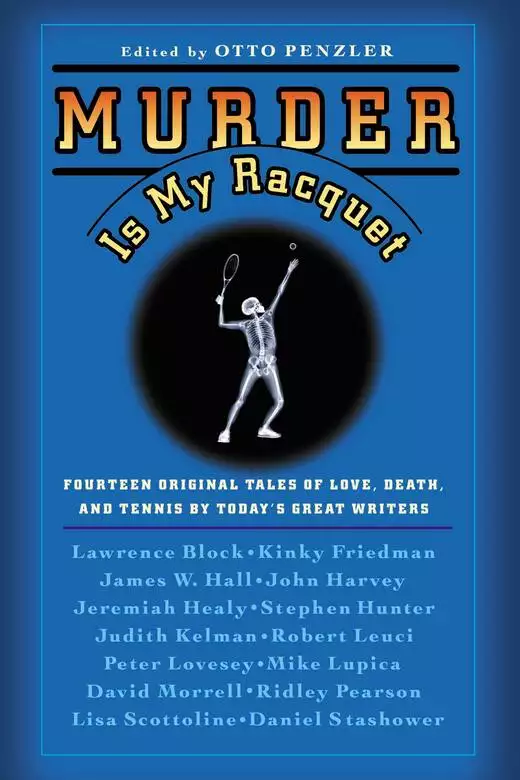

Murder is my Racquet

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Murder is My Racquet is the most thrilling way to read about tennis, murder and intrigue. This collection of stories by famous mystery writers, including Ridley Pearson and Lawrence Block, deal with the prestige of the high-stakes race to become one of the few international tennis stars, the promotional opportunities involved, the elimination of tournament competition, and the strategy of tennis in general. Viewed as an elite game since its beginnings, tennis is the perfect sport for one-on-one play and murder! Authors also include Kinky Friedman, John Harvey, James W. Hall, Lisa Scottoline and many more!

Release date: November 11, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder is my Racquet

Otto Penzler

of hands together, the occasional “well played” acknowledgment.

Look a little closer, however, and the nasty underside of tennis, with its many connections to crime and violence, readily

rises to the surface. The very name itself, tennis, is probably derived from the French word “tenez,” which means “take it.”

No niceties here of accept it, or earn it, or try for it. No, the flat out felonious “take it” is unambiguous in its directive.

And the criminal and murderous connections do not end there. The implicit violence of terms like “overhead smash” and “killer

serve” are far removed from the gentle lawn game of softer imaginations.

The violence of the game is not limited to its terminology. Players are coached to rebuff a charge to the net by smashing

the ball directly at the opponent, resulting in more than one black-and-blue mark, if not worse.

And check out old tapes of John McEnroe and his blood

rage, directed mainly at umpires and linesmen but also at opponents. Yet those actions, when seen from the perspective of

today, seem modulated compared with some of the younger thugs who had the door opened for them by the boorish McEnroe (who,

admittedly, now seems to be somewhat embarrassed by his out-of-control actions).

Also recall Jennifer Capriati being busted on drug charges, and the parental abuse of Mary Pierce’s father, who needed a court

order to stop him from terrorizing his daughter. And let’s not forget the fanatic who rooted so enthusiastically for Steffi

Graf that he attacked her greatest rival, Monica Seles, stabbing her in the back during a match.

No, tennis is not all about gentility—a fact amply illustrated on the following pages. Here, some of the giants of the mystery

genre have brought their murderous intentions to center court.

There’s murder, of course, some of it not terribly genteel at all. You’ll encounter blackmail, voodoo, insanity, and clever

scams. You’ll see that human behavior doesn’t vary that much, whether it’s on the pro tour, at the country club, or on a public

court.

Whether the action is centered on a top-ranked player, a hopeless pitty-pat struggler, or a ball boy, there are always secrets

to keep and mysteries to unravel. And who better to create these mysteries (and solve them) than a gathering of some of the

world’s top-ranked crime writers?

Lawrence Block has received the highest honor bestowed by the Mystery Writers of America: the Grand Master Award for lifetime

achievement. He is also a multiple award winner in both the best novel and best short story categories. The versatile and

prolific Block has produced more than fifty novels and

short story collections, most notably about his tough private eye, Matt Scudder, his comedic bookseller/burglar, Bernie Rhodenbarr,

and his amoral hit man, Keller.

Kinky Friedman has had more than one career. He began as an outrageous country and western singer, leading a group called

Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys. Although the group remained successful, he turned his hand to writing hilarious novels

of crime and murder starring no less formidable a light than Kinky himself. He also once ran for a local office in Texas as

a Republican in a district that was, he reports, 98 percent Democratic. He lost.

James W. Hall began his writing career as a poet but switched to the mystery genre, creating one of Florida’s most memorable

characters in Thorn, the hero of most of his best-selling novels. Hall has been hailed by the San Francisco Chronicle as “brilliant” and by Newsweek as “a poet.” His most recent short story, “Crack,” was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe Award.

John Harvey is one of the best of England’s new breed of gritty noir writers whose ten Charlie Resnick novels have been lavishly

(and justly) praised. Elmore Leonard has compared him to Graham Greene; Jim Harrison has likened him to James Lee Burke and

Elmore Leonard; the London Times has called him “The King of Crime,” and the Denver Post stated unequivocally that “Harvey writes better crime novels than anybody else in the world.”

Jeremiah Healy, creator of the Boston-based private eye John Francis Cuddy, has been nominated for six Shamus Awards by the

Private Eye Writers of America, winning the Best Novel Award for The Staked Goat. Two of his short stories have been selected for the prestigious Best American Mystery Stories of the Year.

Stephen Hunter has become a perennial name on the bestseller list with such gritty thrillers as Hot Springs, Time to Hunt, Point of Impact, and Dirty White Boys. His sometimes shocking adventures of “Bob the Nailer” (and if you haven’t already, read the books so you can learn how he

got the name!) have been applauded by Robert Ludlum (“breathtaking, fascinating”), John Sandford (“Stephen Hunter is Elmore

Leonard on steroids”), and Nelson DeMille (“Stephen Hunter is in a class by himself”).

Judith Kelman is the best-selling author of thirteen novels of psychological suspense, including Summer of Storms, After the Fall, Fly Away Home, and More Than You Know, which have been praised by such masters of the genre as Mary Higgins Clark (“Judith Kelman gets better all the time!”),

Dean Koontz (“swift, suspenseful, highly entertaining”), and Susan Isaacs (“riveting… loaded with suspense, smart characters,

and wonderfully acute observations”).

Robert Leuci was a detective with the New York City Police Department for more than twenty years and served as the subject

of Robert Daley’s best-selling Prince of the City and the motion picture made from it. He is the author of terrifically realistic police novels, including The Snitch and The Blaze, of whom Nicholas Pileggi, author of Wiseguys, has said, “In the writings of the world of cops and the mob, there is no more authentic voice than Bob Leuci’s.”

Peter Lovesey capped a brilliant career by winning the British Crime Writers Association’s highest honor, the Carder Diamond

Dagger Award for lifetime achievement. He began writing in 1970 with Wobble to Death, introducing Sergeant Cribb, who appeared in seven more novels and two television series (seen in the U.S. on PBS’s Mystery!).

Mike Lupica is one of the most talented and honored sportswriters in America. His controversial columns and articles in the

New York Daily News, Esquire, and other publications have helped make him a household name. His weekly appearance on the television series The Sports Reporters has further enhanced his reputation at the top of his field. He has written several mystery novels about Peter Finley, the

first of which, Dead Air, was nominated for an Edgar and then filmed for CBS as Money, Power and Murder.

David Morrell, although a consistent best-seller for nearly twenty years with such novels as The League of Night and Fog, The Brotherhood of the Rose, Desperate Measures, and Extreme Denial, will always be remembered for having created an American icon, Rambo, in his novel First Blood. More than 12 million copies of his novels are in print in the United States.

Ridley Pearson won the American Library Association’s Best Fiction Award in 1994 for No Witnesses. He has been a best-seller ever since with such books as Beyond Recognition, The Pied Piper, Middle of Nowhere, and The First Victim. He has been translated into more than twenty languages, and his Lou Boldt series is being produced as an A&E original movie.

Lisa Scottoline, called “the female John Grisham” by People magazine, has had numerous New York Times best-sellers, including Mistaken Identity, Moment of Truth, and The Vendetta Defense. She won an Edgar Allan Poe Award for her second legal thriller, Final Appeal. Her books are regularly used by bar associations to illustrate issues of legal ethics.

Daniel Stashower was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe Award for his first novel, The Adventure of the Ectoplasmic Man, and won the coveted award for Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. In between, he won the Raymond Chandler Ful-bright

Fellowship in Detective and Crime Writing and spent much of his time in Oxford researching his definitive biography.

So these are the players—not seeded, as each of them has a game worth watching. There are hard hitters here, as well as devious

ones. Enjoy the smashes and the lobs, but beware these killer writers because Murder Is Their Racquet.

—Otto Penzler

LAWRENCE BLOCK

As every high school chemistry student knows,” wrote sportswriter Garland Hewes, “the initials TNT stand for tri-nitro-toluene,

and the compound so designated is an explosive one indeed. And, as every tennis fan is by now aware, the same initials stand

as well for Thomas Norton Terhune, supremely gifted, immensely personable, and, as he showed us once again yesterday on the

clay courts of Roland Garros, an unstable and violently explosive mixture if ever there was one, and a grave danger to himself

and others.”

The incident to which the venerable Hewes referred was one of many in Tommy Terhune’s career in world-class tennis. In the

French Open’s early rounds, he dazzled players and spectators alike with the brilliance of his play. His serve was powerful

and on-target, but it was his inspired all-around play that lifted him above the competition. He was quick as a cat, covering

the whole court, making impossible returns look easy. His drop shots dropped, his lobs landed just out of his opponent’s reach

but just inside the white line.

But when the ball was out, or, more to the point, when the umpire declared it to be out, Tommy exploded.

In his quarterfinal match at Roland Garros, a shot of Terhune’s, just eluding the outstretched racquet of his Montenegrin

opponent, landed just inside the baseline.

The umpire called it out.

As the television replay would demonstrate, time and time again, the call was an error on the official’s part. The ball did

in fact land inside the line, by two or three inches. Thus Tommy Terhune was correct in believing that the point should be

his, and he was understandably dismayed at the call.

His behavior was less understandable. He froze at the call, his racquet at shoulder height, his mouth open. While the crowd

watched in anticipatory silence, he approached the umpire’s raised platform. “Are you out of your mind?” he shouted. “Are

you blind as a bat? What the hell is the matter with you, you pop-eyed frog?”

The umpire’s response was inaudible, but was evidently uttered in support of his decision. Tommy paced to and fro at the foot

of the platform, ranting, raving, and drawing whistles of disapproval from the fans. Then, after a tense moment, he returned

to the baseline and prepared to serve.

Two games later in the same set, he let a desperate return of his opponent’s drop. It was long, landing a full six inches

beyond the white line. The umpire declared it in, and Tommy went berserk. He screamed, he shouted, he commented critically

on the umpire’s lineage and sexual predilections, and he underscored his remarks by gripping his racquet in both hands, then

swinging it like an axe as if to chop down the wooden platform, perhaps as a first step to chopping down the official himself.

He managed to land three ringing blows, the third of

which shattered his graphite racquet, before another official stepped in to declare the match a forfeit, while security personnel

took the American in hand and led him off the court.

The French had never seen the like and, characteristically, their reaction combined distaste for Terhune’s lack of savoir-faire

with grudging respect for his spirit. Phrases like enfant terrible and monstre sacre turned up in their press coverage. Elsewhere in the world, fans and journalists said essentially the same thing. Terrible

Tommy Terhune, the tennis world’s most gifted and most temperamentally challenged player, had proven to be his own worst enemy,

and had succeeded in ousting himself from a tournament he’d been favored to win. He had done it again.

• • •

The racquet Tommy shattered at the French Open was not the first one to go to pieces in his hands. His racquets had the life

expectancy of a rock star’s guitar, and he consequently had learned to travel with not one but two spares. Even so, he’d been

forced to withdraw from one tournament in the semifinal round, when, after a second double fault, he held his racquet high

overhead, then brought it down full-force upon the hardened playing surface. He had already sacrificed his other two racquets

in earlier rounds, one destroyed in similar fashion to protest an official’s decision, the other snapped over his knee in

fury at himself for a missed opportunity at the net. He was now out of racquets, and unable to continue. His double fault

had cost him a point; his ungovernable rage had cost him the tournament.

Such episodes notwithstanding, Tommy won his share of tournaments. He did not always blow up, and not every

episode led to disqualification. In England, one confrontation with an official provoked a clamor in the press that he be

refused future entry, not merely to Wimbledon, but to the entire United Kingdom; in response, Tommy somehow held himself in

check long enough to breeze through the semifinals, and, in the final round, treated the fans to an exhibition of play unlike

anything they’d seen before.

Playing against Roger MacReady, the rangy Australian who was the crowd’s clear favorite, Tommy played Centre Court at Wimbledon

as Joe DiMaggio had once played center field at Yankee Stadium. He anticipated every move MacReady made, moving in response

not at the impact of ball and racquet but somehow before it, as if he knew where MacReady was going to send the ball before

the Australian knew it himself. He won the first two sets, lost the third in a tiebreaker, and soared to an easy victory in

the fourth set, winning 6–1, and winning over the crowd in the process. By the time his last impossible backhand return had

landed where MacReady couldn’t get to it, the English fans were on their feet cheering for him.

A month later, the laurels of Wimbledon still figuratively draped around his shoulders, Terrible Tommy Terhune diagnosed an

official as suffering severely from myopia, astigmatism, and tunnel vision, and recommended an unorthodox course of ophthalmological

treatment consisting of the performance of two sexual acts, one incestuous, the other physically impossible. He then threw

his racquet on the ground, stepped on its face, and pulled up on its handle until the thing snapped. He picked up the two

pieces, sailed them into the crowd, and stalked off the court.

• • •

Morley Safer leaned forward. “If you were watching a tennis match,” he began, “and saw someone behave as you yourself have

so often behaved—”

“I’d be disgusted,” Tommy told him. “I get sick to my stomach when I see myself on videotape. I can’t watch. I have to turn

off the set. Or leave the room.”

“Or pick up a racquet and smash the set?”

Tommy laughed along with the TV newsman, then assured him that his displays of temper were confined to the tennis court. “That’s

the only place they happen,” he said. “As to why they happen, well, I know what provokes them. I get mad at myself when I

play poorly, of course, and that’s led me to smash a racquet now and then. It’s stupid and self-destructive, sure, but it’s

nothing compared to what happens when an official makes a bad call. That drives me out of my mind.”

“And out of control?”

“I’m afraid so.”

“And yet there are skeptics who think you’re crazy like a fox,” Safer said. “Look at the publicity you get. After all, you’re

the subject of this 60 Minutes profile, not Vasco Barxi, not Roger MacReady. All over the world, people know your name.”

“They know me as a maniac who can’t control himself. That’s not how I want to be known.”

“And there are others who say you gain by intimidating officials,” Safer went on. “You get them so they’re afraid to call

a close point against you.”

“They seem to be dealing with their fears,” Tommy said. “And wouldn’t that be brilliant strategy on my part? Get tossed out

of a Grand Slam tournament in order to unnerve an official?”

“So it’s not calculated? In fact it’s not something subject to your control?”

“Of course not.”

“Well, what are you going to do about it? Are you getting help?”

“I’m working on it,” he said grimly. “It’s not that easy.”

• • •

“It’s rage,” he told Diane Sawyer. “I don’t know where it comes from. I know what triggers it, but that’s not necessarily the

same thing.”

“A bad call.”

“That’s right.”

“Or a good call,” Sawyer said, “that you think is a bad call.”

Tommy shook his head ruefully. “It’s embarrassing enough to explode when the guy gets it wrong,” he said. “The incident I

think you’re referring to, where the replay clearly showed he’d made the right call, well, I felt more ashamed of myself than

ever. But even when I’m clearly right and the official’s clearly wrong, there’s no excuse for my behavior.”

“You realize that.”

“Of course I do. I may be crazy, but I’m not stupid.”

“And if you are crazy, it’s temporary insanity. As I think our viewers can see, you’re perfectly sane when you don’t have a tennis racquet

in your hand.”

“Well, they haven’t asked me to pose for any Mental Health posters,” he said with a grin. “But it’s true I don’t have to struggle

to keep a lid on it. That only happens when I’m playing tennis.”

“The court’s where the struggle takes place.”

“Yes.”

“And when you honestly think a call has gone against you, that it’s a bad call…”

“Sometimes I can keep myself in check. But other times I just lose it. I go into a zone and, well, everybody knows what happens

then.”

“And there’s nothing you can do about it.”

“Not really.”

“You’ve had professional help?”

“I’ve tried a few things,” he said. “Different kinds of therapy to help me develop more insight into myself. I think it’s

been useful, I think I know myself a little better than I used to, but when some clown says one of my shots was out when I

just plain know it was in—”

“You’re helpless.”

“Utterly,” he said. “Everything goes out the window, all the insight, all the coping techniques. The only thing that’s left

is the rage.”

• • •

“You have a life most women would envy,” Barbara Walters told Jennifer Terhune. “You’re young, you’re beautiful, you’ve had

success as a model and as an actress. And you’re the wife of an enormously talented and successful athlete.”

“I’ve been very fortunate.”

“What’s it like being married to a man like Tommy Terhune?”

“It’s wonderful.”

“The clothes, the travel, the VIP treatment…”

“That’s all nice,” Jennifer acknowledged, “but it’s, like, the least of it. Just being with Tommy, sharing his life, that’s

what’s truly wonderful.”

“You love your husband.”

“Of course I do.”

“But I’m sure there are women in my audience,” Walters said, “who wonder if you might not be the least bit afraid of your

husband.”

“Afraid of Tommy?”

Walters raised her eyebrows. “Mr. TNT? Terrible Tommy Terhune?”

“Oh, that.”

“ ‘Oh, that.’ You’re married to a man with the most famously explosive temper in the world. Don’t tell me you’re never afraid

that something you might do or say will set him off.”

“Not really.”

“What makes you so confident, Jennifer?”

“Tommy has a problem with rage,” Jennifer said, “and I recognize it, and he recognizes it. He’s been working on it, trying a lot of different things, like, to help him cope with it. I just know he’ll

be able to get a handle on it.”

“And I’m sure our hopes are with him,” Walters said, “but that doesn’t address the question, does it? What about you, Jennifer?

How do you know that terrible temper, that legendary rage, won’t one day be aimed at you?”

“I’m not an umpire.”

“In other words…”

“In other words, the only time Tommy loses it, the only time his temper is the least bit of a problem, is when an official

makes a bad call against him on the tennis court. He never gets mad at an opponent. He doesn’t go into the stands after fans

who make insulting remarks, and I’ve heard some of them say some pretty outrageous things. But he

takes that sort of thing in stride. It’s only bad calls that set him off.”

“And after an explosion?”

“He’s contrite. And ashamed of himself.”

“And angry?”

“Only during a match. Not afterward.”

“So it’s never directed at you?”

“Never.”

“He’s a perfect gentleman?”

“He’s thoughtful and gentle and funny and smart,” Jennifer said, “in addition to being the best tennis player in the world.

I’m a lucky girl.”

Later, watching herself on television, Jennifer thought the interview had gone rather well. She sounded a little ditsy, saying

like often enough to sound like a Valley Girl, but outside of that she’d done fine. Her hair, which had caused her some concern,

wound up looking great on camera, and the dress she’d worn had proved a good choice.

And her comments seemed okay, too. The likes notwithstanding, she came across not as an airhead but as a concerned and supportive life partner and helpmate. And, she

told herself, that was fair enough. Everything she’d said had been the truth.

Though not, she had to admit, the whole truth. Because how could she have sat there and told Barbara Walters that Tommy’s

temper was one of the things that had attracted her to him in the first place? All of that intensity, when he served and volleyed

and made impossible shots look easy, well, it was exciting enough. But all of that passion, when he roared and ranted and

just plain lost it, was even more exciting. It stirred her up, it got her juices flowing. It made her, well, hot—and how could she say all that to Barbara Walters?

In fact, when you came right down to it, she was a little disappointed that Tommy never lost it except on the tennis court.

It was a pity, in a way, that he never brought that famous temper home with him, that he never lost it in the bedroom.

Sometimes—and she would never admit this to anyone, on or off camera—sometimes she tried to provoke him. Sometimes she tried

to make him mad. Even if he were to get physical, even if he were to slap her around a little, well, maybe it was kinky of

her, but she thought she might like that.

But it was hopeless. On the court, with a racquet in his hand and an official to argue with, he was Mr. TNT, the notorious

Terrible Tommy Terhune. At home, even in the bedchamber, he was what she’d said he was, the perfect gentleman.

Darn it…

• • •

“So we begin to make progress,” the psychoanalyst said. “The need to win your father’s approval. The approval sometimes granted,

other times withheld, for reasons having nothing to do with your own behavior.”

“It wasn’t fair,” Tommy said.

“And that is what so infuriates you about a bad call on the tennis court, is it not so? The unfairness of it all. You have

done everything you were supposed to do, everything within your power, and still the approval of the man in authority is denied

to you. Instead he sits high above you, remote and unreachable, and punishes you.”

“That’s exactly what happens.”

“And it is unfair.”

“Damn right it is.”

“And you explode in rage, the rage you never let yourself

feel as a child. But now you know its source. It’s not the official, who of course cannot be expected to be right every time.”

“They’re only human.”

“Exactly. It’s your father you’re truly enraged at, and he’s dead, and out of reach of your anger, no longer available to

approve or disapprove, to applaud or punish.”

“That’s it, all right.”

“And now, armed with the insight you’ve developed here, you’ll be able to master your rage, to dispel it, to rise above it.”

“You know something?” Tommy said. “I feel better already.”

• • •

In a first-round match two weeks later, an unreturnable passing shot by his unseeded opponent fell just outside the sideline

marker. The umpire called it in.

“You blind bastard!” Tommy screamed. “How much are they paying you to steal the match from me?”

• • •

“With every breath,” the little man in the loincloth intoned, “you draw the anger up from the third chakra. Up up up, past the

heart chakra, past the throat chakra, to the third eye. Then, as you breathe out, you let the anger flow in a stream out through

the third eye, transformed into peaceful energizing white light. Breathe in and the anger is drawn upward from the solar plexus

where it is stored. Breathe out and you release it as white light. With every breath, your reserve of rage grows less and

less.”

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...