- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

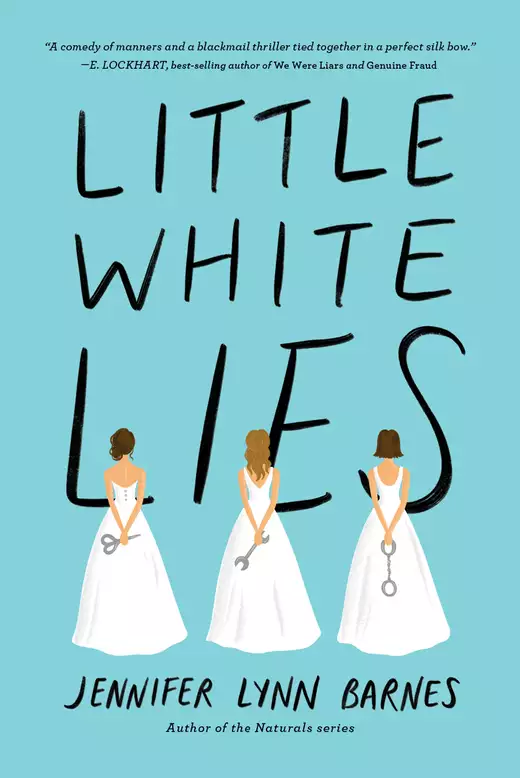

Synopsis

When Sawyer Taft agrees to move in with her grandmother, she expects some things to be different, but what she doesn't expect is to get sucked into a group of over-privileged, yet somehow lovable debs who have — wait for it — kidnapped one of their own in hopes of blackmailing her into keeping their secrets under wraps — secrets that are far bigger and more scandalous than anyone could have imagined. As Sawyer works to uncover the identity of her father, she must also navigate the twisted relationships between her new friends and their powerful parents and help them discover the villain among them.

Set in the gentrified south among debutante balls, grand estates, and rolling green hills, Little White Lies combines the charm of a fully-realized setting, a classic fish-out-of-water story, and the sort of layered mystery only Jennifer Lynn Barnes can pull off.

Release date: November 4, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Little White Lies

Jennifer Lynn Barnes

“No way. I took the drunk tank after the Bison Day parade.”

“Bison Day? Try Oktoberfest at the senior citizen center.”

“And who got stuck with the biter the next day?”

Officer Macalister Dodd—Mackie to his friends—had the general sense that it would not be prudent to interrupt the back-and-forth between the two more senior Magnolia County police officers arguing in the bull pen. Rodriguez and O’Connell had both clocked five years on the force.

This was Mackie’s second week.

“I’ve got three letters and one word for you, Rodriguez: PTA brawl.”

Mackie shifted his weight slightly from his right leg to his left. Big mistake. In unison, Rodriguez and O’Connell turned to look at him.

“Rookie!”

Never had two police officers been so delighted to see a third. Mackie set his mouth into a grim line and squared his shoulders.

“What have we got?” he said gruffly. “Drunk and disorderly? Domestic disturbance?”

In answer, O’Connell clapped him on the shoulder and steered him toward the holding cell. “Godspeed, rookie.”

As they rounded the corner, Mackie expected to see a perp: belligerent, possibly on the burly side. Instead, he saw four teenage girls wearing elbow-length gloves and what appeared to be ball gowns.

White ball gowns.

“What the hell is this?” Mackie asked.

Rodriguez lowered his voice. “This is what we call a BYH.”

“BYH?” Mackie glanced back at the girls. One of them was standing primly, her gloved hands folded in front of her body. The girl next to her was crying daintily and wheezing something that sounded suspiciously like the Lord’s Prayer. The third stared straight at Mackie, the edges of her pink-glossed lips quirking slowly upward as she raked her gaze over his body.

And the fourth girl?

She was picking the lock.

The other officers turned to leave.

“Rodriguez?” Mackie called after them. “O’Connell?”

No response.

“What’s a BYH?”

The girl who’d been assessing him took a step forward. She batted her eyelashes at Mackie and offered him a sweet-tea smile.

“Why, Officer,” she said. “Bless your heart.”

atcalling me was a mistake that most of the customers and mechanics at Big Jim’s Garage only made once. Unfortunately, the owner of this particular Dodge Ram was the type of person who put his paycheck into souping up a Dodge Ram. That—and the urinating stick figure on his back window—was pretty much the only forewarning I needed about the way this was about to go down.

People were fundamentally predictable. If you stopped expecting them to surprise you, they couldn’t disappoint.

And speaking of disappointment… I turned my attention from the Ram’s engine to the Ram’s owner, who apparently considered whistling at a girl to be a compliment and commenting on the shape of her ass to be the absolute height of courtship.

“It’s times like this,” I told him, “that you have to ask yourself: Is it wise to sexually harass someone who has both wire cutters and access to your brake lines?”

The man blinked. Once. Twice. Three times. And then he leaned forward. “Honey, you can access my brake lines anytime you want.”

If you know what I mean, I added silently. In three… two…

“If you know what I mean.”

“It’s times like this,” I said meditatively, “that you have to ask yourself: Is it wise to offer to bare your man-parts for someone who is both patently uninterested and holding wire cutters?”

“Sawyer!” Big Jim intervened before I could so much as give a snip of the wire cutters in a southward direction. “I’ve got this one.”

I’d started badgering Big Jim to let me get my hands greasy when I was twelve. He almost certainly knew that I’d already fixed the Ram, and that if he left me to my own devices, this wouldn’t end well.

For the customer.

“Aw hell, Big Jim,” the man complained. “We were just having fun.”

I’d spent most of my childhood going from one obsessive interest to another. Car engines had been one of them. Before that, it had been telenovelas, and afterward, I’d spent a year reading everything I could find about medieval weapons.

“You don’t mind a little fun, do you, sweetheart?” Mr. Souped-Up Dodge Ram clapped a hand onto my shoulder and compounded his sins by squeezing my neck.

Big Jim groaned as I turned my full attention to the real charmer beside me.

“Allow me to quote for you,” I said in an absolute deadpan, “from Sayforth’s Encyclopedia of Archaic Torture.”

One of the finer points of chivalry in my particular corner of the South was that men like Big Jim Thompson didn’t fire girls like me no matter how explicitly we described alligator shears to customers in want of castration.

Fairly certain I’d ensured the Ram’s owner wouldn’t make the same mistake a third time, I stopped by The Holler on the way home to pick up my mom’s tips from the night before.

“How’s trouble?” My mom’s boss was named Trick. He had five children, eighteen grandchildren, and three visible scars from breaking up bar fights—possibly more under his ratty white T-shirt. He’d greeted me the exact same way every time he’d seen me since I was four.

“I’m fine, thanks for asking,” I said.

“Here for your mom’s tips?” That question came from Trick’s oldest grandson, who was restocking the liquor behind the bar. This was a family business in a family town. The entire population was just over eight thousand. You couldn’t throw a rock without it bouncing off three people who were related to each other.

And then there was my mom—and me.

“Here for tips,” I confirmed. My mom wasn’t exactly known for her financial acumen or the steadfastness with which she made it home after a late shift. I’d been balancing our household budget since I was nine—around the same time that I’d developed sequential interests in lock picking, the Westminster Dog Show, and fixing the perfect martini.

“Here you go, sweetheart.” Trick handed me an envelope that was thicker than I’d expected. “Don’t blow it all in one place.”

I snorted. The money would go to rent and food. I wasn’t exactly the type to party. I might, in fact, have had a bit of a reputation for being antisocial.

See also: my willingness to threaten castration.

Before Trick could issue an invitation for me to join the whole family at his daughter-in-law’s house for dinner, I made my excuses and ducked out of the bar. Home sweet home was only two blocks over and one block up. Technically, our house was a one-bedroom, but we’d walled off two-thirds of the living room with dollar-store shower curtains when I was nine.

“Mom?” I called out as I stepped over the threshold. There was an element of ritual to calling her name, even when she wasn’t home. Even if she was on a bender—or if she’d fallen for a new man, experienced another religious conversion, or developed a deep-seated need to commune with her better angels under the watchful eyes of a roadside psychic.

I’d come by my habit of hopping from one interest to the next honestly, even if her restlessness was less focused and a little more self-destructive than my own.

Almost on cue, my cell phone rang. I answered.

“Baby, you will not believe what happened last night.” My mom never bothered with salutations.

“Are you still in the continental United States, are you in need of bail money, and do I have a new daddy?”

My mom laughed. “You’re my everything. You know that, right?”

“I know that we’re almost out of milk,” I replied, removing the carton from the fridge and taking a swig. “And I know that someone was an excellent tipper last night.”

There was a long pause on the other end of the line. I’d guessed correctly this time. It was a guy, and she’d met him at The Holler the night before.

“You’ll be okay, won’t you?” she asked softly. “Just for a few days?”

I was a big believer in absolute honesty: Say what you mean, mean what you say, and don’t ask a question if you don’t want to know the answer.

But it was different with my mom.

“I reserve the right to assess the symmetry of his features and the cheesiness of his pickup lines when you get back.”

“Sawyer.” My mom was serious—or at least as serious as she got.

“I’ll be fine,” I said. “I always am.”

She was quiet for several seconds. Ellie Taft was many things, but above all, she was someone who’d tried as hard as she could for as long as she could—for me.

“Sawyer,” she said quietly. “I love you.”

I knew my line, had known it since my brief obsession with the most quotable movie lines of all time when I was five. “I know.”

I hung up the phone before she could. I was halfway to finishing off the milk when the front door—in desperate need of both WD-40 and a new lock—creaked open. I turned toward the sound, running the algorithm to determine who might be dropping by unannounced.

Doris from next door lost her cat an average of 1.2 times per week.

Big Jim and Trick had matching habits of checking up on me, like they couldn’t remember I was eighteen, not eight.

The guy with the Dodge Ram. He could have followed me. That wasn’t a thought so much as instinct. My hand hovered over the knife drawer as a figure stepped into the house.

“I do hope your mother buys Wüsthof,” the intruder commented, observing the position of my hand. “Wüsthof knives are just so much sharper than generic.”

I blinked, but when my eyes opened again, the woman was still standing there, coiffed within an inch of her life and besuited in a blue silk jacket and matching skirt that made me wonder if she’d mistaken our decades-old house for a charitable luncheon. The stranger said nothing to indicate why she’d let herself in or how she could justify sounding more dismayed at the idea of my mom having purchased off-brand knives than the prospect that I might be preparing to draw one.

“You favor your mother,” she commented.

I wasn’t sure how she expected me to reply to that statement, so I went with my gut. “You look like a bichon frise.”

“Pardon me?”

It’s a breed of dog that looks like a very small, very sturdy powder puff. Since absolute honesty didn’t require that I say every thought that crossed my mind, I opted for a modified truth. “You look like your haircut cost more than my car.”

The woman—I put her age in her early sixties—tilted her head slightly to one side. “Is that a compliment or an insult?”

She had a Southern accent—less twang and more drawl than my own. Com-pluh-mehnt or an in-suhlt?

“That depends on your perspective more than mine.”

She smiled slightly, like I’d said something just darling, but not actually amusing. “Your name is Sawyer.” After informing me of that fact, she paused. “You don’t know who I am, do you?” Clearly, that was a rhetorical question, because she didn’t wait for a reply. “Why don’t I spare us the dramatics?”

Her smile broadened, warm in the way that a shower is warm, right before someone flushes the toilet.

“My name,” she continued in a tone to match the smile, “is Lillian Taft. I’m your maternal grandmother.”

My grandmother, I thought, trying to process the situation, looks like a bichon frise.

“Your mother and I had a bit of a falling-out before you were born.” Lillian was apparently the kind of person who would have referred to a Category 5 hurricane as a bit of a drizzle. “I think it’s high time to put that bit of history to rest, don’t you?”

I was one rhetorical question away from going for the knife drawer again, so I attempted to cut to the chase. “You didn’t come here looking for my mother.”

“You don’t miss much, Miss Sawyer.” Lillian’s voice was soft and feminine. I got the feeling she didn’t miss much, either. “I’d like to make you an offer.”

An offer? I was suddenly reminded of who I was dealing with here. Lillian Taft wasn’t a powder puff. She was the merciless, dictatorial matriarch who’d kicked my pregnant mother out of her house at the ripe old age of seventeen.

I stalked to the front door and retrieved the Post-it I’d placed next to the doorbell when our house had been hit with door-to-door evangelists two weeks in a row. I turned and offered the handwritten notice to the woman who’d raised my mother. Her perfectly manicured fingertips plucked the Post-it from my grasp.

“ ‘No soliciting,’ ” my grandmother read.

“Except for Girl Scout cookies,” I added helpfully. I’d gotten kicked out of the local Scout troop during my morbid true-crime and facts-about-autopsies phase, but I still had a weakness for Thin Mints.

Lillian pursed her lips and amended her previous statement. “ ‘No soliciting except for Girl Scout cookies.’ ”

I saw the precise moment that she registered what I was saying: I wasn’t interested in her offer. Whatever she was selling, I wasn’t buying.

An instant later, it was like I’d said nothing at all. “I’ll be frank, Sawyer,” she said, showing a kind of candy-coated steel I’d never seen in my mom. “Your mother chose this path. You didn’t.” She pressed her lips together, just for a moment. “I happen to think you deserve more.”

“More than off-brand knives and drinking straight from the carton?” I shot back. Two could play the rhetorical-question game.

Unfortunately, the great Lillian Taft had apparently never met a rhetorical question she was not fully capable of answering. “More than a GED, a career path with no hope of advancement, and a mother who’s less responsible now than she was at seventeen.”

Were she not an aging Southern belle with a reputation to uphold, my grandmother might have followed that statement by throwing her hands into touchdown position and declaring, “Burn!”

Instead, she laid a hand over her heart. “You deserve opportunities you’ll never have here.”

The people in this town were good people. This was a good place. But it wasn’t my place. Even in the best of times, part of me had always felt like I was just passing through.

A muscle in my throat tightened. “You don’t know me.”

That got a pause out of her—and not a calculated one. “I could,” she replied finally. “I could know you. And you could find yourself in the position to attend any college of your choosing and graduate debt-free.”

here was a contract. An honest-to-God, written-in-legalese, sign-on-the-dotted-line contract.

“Seriously?”

Lillian waved away the question. “Let’s not get bogged down in the details.”

“Of course not,” I said, thumbing through the nine-page appendix. “Why would I go to the trouble of reading the terms before I sell you my soul?”

“The contract is for your protection,” my grandmother insisted. “Otherwise, what’s to keep me from reneging on my end of the deal once yours is complete?”

“A sense of honor and any desire whatsoever for an ongoing relationship?” I suggested.

Lillian arched an eyebrow. “Are you willing to bet your college education on my honor?”

I knew plenty of people who’d gone to college. I also knew a lot of people who hadn’t.

I read the contract. I wasn’t even sure why. I was not going to move in with her. I was not going to walk away from my home, my life, my mother for—

“Five hundred thousand dollars?” I may have punctuated that amount with an expletive or two.

“Have you been listening to rap music?” my grandmother demanded.

“You said you’d pay for college.” I tore my gaze from the contract. Even reading it made me feel like I’d just let the guy with the Dodge Ram tuck a couple of ones into my bikini. “You didn’t say anything about handing me a check for half a million dollars.”

“It won’t be a check,” my grandmother said, as if that was the real issue here. “It will be a trust. College, graduate school, living expenses, study abroad, transportation, tutors—these things add up.”

These things.

“Say it,” I told her, unable to believe that anyone could shrug off that amount of money. “Say that you’re offering me five hundred thousand dollars to live with you for nine months.”

“Money isn’t something we talk about, Sawyer. It’s something we have.”

I stared at her, waiting for the punch line.

There was no punch line.

“You came here expecting me to say yes.” I didn’t phrase that sentence as a question, because it wasn’t one.

“I suppose that I did,” Lillian allowed.

“Why?”

I wanted her to actually say that she’d assumed that I could be bought. I wanted to hear her admit that she thought so little of me—and so little of my mom—that there had been no doubt in her mind that I’d jump at the chance to take her devil of a deal.

“I suppose,” Lillian said finally, “that you remind me a bit of myself. And were I in your position, sweet girl…” She laid a hand on my cheek. “I would surely jump at the chance to identify and locate my biological father.”

y mom—in between alternating bouts of pretending that I’d been immaculately conceived, cursing the male of the species, and getting tipsy and nostalgic about her first time—had told me exactly three things about my mystery father.

She’d only slept with him once.

He hated fish.

He wasn’t looking for a scandal.

And that was it. When I was eleven, I’d found a picture she’d hidden away, a portrait of twenty-four teenage boys in long-tailed tuxedos standing beneath a marble arch.

Symphony Squires.

The caption had been embossed onto the picture in silver script. The year—and several of the faces—had been scratched out.

Money isn’t something we talk about, I thought hours after Lillian had left. I mentally mimicked her tone as I continued. And the fact that the man who knocked your mother up is almost certainly a scion of high society isn’t something I’ll come right out and say, but…

I picked the contract up again. This time, I read it from start to finish. Lillian had conveniently forgotten to mention some of the terms.

Like the fact that she would choose my wardrobe.

Like the mandatory manicure I’d have once a week.

Like the way she expected me to attend private school alongside my cousins.

I hadn’t even realized I had cousins. Trick’s grandkids had cousins. Half of the members of my elementary school Girl Scout troop had cousins in that troop. But me?

I had an encyclopedia of medieval torture techniques.

Pushing myself to finish the contract, I arrived at the icing on the cake. I agree to participate in the annual Symphony Ball and all Symphony Deb events leading up to my presentation to society next spring.

Deb. As in debutante.

Half a million dollars wasn’t enough.

And yet, the thought of those hypothetical cousins lingered in my mind. One of my less random childhood obsessions had been genetics. Cousins shared roughly one-eighth of their DNA.

Half-siblings share a fourth. I found myself going to my mother’s bedroom, opening the bottom drawer of her dresser, and feeling for the photograph she’d taped to the back.

Twenty-four teenage boys.

Twenty-four possible producers of the sperm that had impregnated my mother.

Twenty-four Symphony Squires.

When my phone buzzed, I forced myself to shut the drawer and looked down at the text my mom had just sent me.

A photo of an airplane.

It may be more than a few days. I read the message that had accompanied the photograph silently and then a second time out loud. My mother loved me. I knew that. I’d always known that.

Someday, I’d stop expecting her to surprise me.

It was another hour before I went back to the contract. I picked up a red pen. I made some adjustments.

And then I signed.

arrived at my grandmother’s residence—a mere forty-five minutes from the town where I’d grown up and roughly three and a half worlds away—on the contractually specified date at the contractually specified time. Based on what I knew of the Taft family and the suburban wonderland they inhabited, I’d expected my grandmother’s house to be a mix of Tara and the Taj Mahal. But 2525 Camellia Court wasn’t ostentatious, and it wasn’t historic. It was a nine-thousand-square-foot house masquerading as average, the architectural equivalent of a woman who spent two hours making herself up for the purpose of looking like she wasn’t wearing makeup. This old thing? I could almost hear the two-acre lot saying. I’ve had it for years.

Objectively, the house was enormous, but the cul-de-sac was lined with other houses just as big, with lawns just as sprawling. It was like someone had taken a normal neighborhood and scaled everything up an order of magnitude—including the driveways, the SUVs, and the dogs.

The single largest canine I’d ever seen greeted me at the front door, butting my hand with its massive head.

“William Faulkner,” the woman who’d answered the door chided. “Mind your manners.”

She was the spitting image of Lillian Taft. I was still processing the fact that the dog was (a) the size of a small pony and (b) named William Faulkner, when the woman I assumed was my aunt spoke again.

“John David Easterling,” she called, raising her voice so it carried. “Who’s the best shot in this family?”

There was no reply. William Faulkner butted his head against my thigh and huffed. I bent slightly—very slightly—to pet him and noticed the red dot that had appeared on my tank top.

“I will skin you alive if you pull that trigger,” my aunt called, her voice disturbingly cheerful.

What trigger? I thought. The red dot on my torso wavered slightly.

“Now, young man, I believe I asked you a question. Who’s the best shot in this family?”

There was an audible sigh, and then a boy of ten or so pushed up to a sitting position on the roof. “You are, Mama.”

“And am I using your cousin for target practice?”

“No, ma’am.”

“No, sir, I am not,” my aunt confirmed. “Sit, William Faulkner.”

The dog obeyed, and the boy disappeared from the roof.

“Please tell me that was a Nerf gun,” I said.

It took my aunt a moment to process the question and then she let out a peal of laughter—practiced and perfect. “He’s not allowed to use the real thing without supervision,” she assured me.

I stared at her. “That’s not as comforting as you think it is.”

The smile never left her face. “You do look like your mother, don’t you? That hair. And those cheekbones! When I was your age, I would have killed for those cheekbones.”

Given that she was the best shot in this family, I wasn’t entirely certain she was exaggerating.

“I’m Sawyer,” I said, trying to wrap my mind around the greeting I’d gotten from a woman my mom had always referred to as an ice queen.

“Of course you are,” came the immediate reply, warm as whiskey. “I’m your aunt Olivia, and that’s William Faulkner. She’s a purebred Bernese mountain dog.”

I’d recognized the breed. What I hadn’t recognized, however, was that William Faulkner was female.

“Where’s Lillian?” I asked, feeling like I’d well and truly fallen down the rabbit hole.

Aunt Olivia hooked the fingers on her right hand through William Faulkner’s collar and reflexively straightened her pearls with the left. “Let’s get you inside, Sawyer. Are you hungry? You must be hungry.”

“I just ate,” I replied. “Where’s Lillian?”

My aunt ignored the question. She was already retreating back into the house. “Come on, William Faulkner. Good girl.”

My grandmother’s kitchen was the size of our entire house. I half expected my aunt to ring for the cook, but it quickly became apparent that she considered the feeding of other people to be both a pastime and a spiritual calling. Nothing I said or did could dissuade her from making me a sandwich.

Refusing the brownie might have been taken as a declaration of war.

I was a big believer in personal boundaries, but I was also a believer in chocolate, so I ignored the sandwich, took a bite of the brownie, and then asked where my grandmother was.

Again.

“She’s out back with the party planner. Can I get you something to drink?”

I put the brownie back down on my plate. “Party planner?”

Before my aunt could answer, the boy who’d had me in his sights earlier appeared in the kitchen. “Lily says it’s bad manners to threaten fratricide,” he announced. “So she didn’t threaten fratricide.”

He helped himself to the seat next to mine and eyed my sandwich. Without a word, I slid it toward him, and he began devouring it with all the verve of a little Tasmanian devil wearing a blue polo shirt.

“Mama,” he said after swallowing. “What’s fratricide?”

“I imagine it’s what one’s sister very pointedly does not threaten when one attempts to shoot her with a Nerf gun.” Aunt Olivia turned back to the counter. It took me about three seconds to realize that she was making another sandwich. “Introduce yourself, John David.”

“I’m John David. It’s a pleasure to meet you, madam.” For a trigger-happy kid, he was surprisingly gallant when it came to introductions. “Are you here for the party?”

I narrowed my eyes slightly. “What party?”

“Incoming!” A man swept into the room. He had presidential hair and a face made for golf courses and boardrooms. I would have pegged him as Aunt Olivia’s husband even if he hadn’t bent to kiss her cheek. “Fair warning: I saw Greer Richards making her way down the street on my way in.”

“Greer Waters now,” my aunt reminded him.

“Ten-to-on. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...