- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

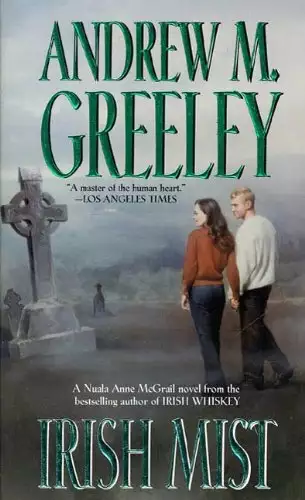

Andrew M. Greeley's bestselling Nuala Anne McGrail mystery series returns with the fourth installment, Irish Mist

Dermot Michael Coyne isn't sure what he's gotten himself into. Nuala Anne McGrail, that beautiful and vivacious "Celtic witch" has finally agreed to marry him. But they've barely tied the knot when Nuala's psychic "spells" begin again. Visions of a burning castle, the captain of the infamous "Black and Tan" police force, a wild woman from Chicago, and bloodshed--all somehow connected--lead the two to the remnants of a mystery long buried in the mist of Ireland's turbulent and violent past. How did Kevin O'Higgins, the murdered leader of the movement to free Ireland, die? And who among the living will do whatever it takes to keep Nuala and Dermot from finding out?

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: March 1, 2000

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Irish Mist

Andrew M. Greeley

"WERE YOU" the fella with whom I slept last night?"

The women opened her eyes and peered at me.

"I was."

She closed her eyes again.

"How was I?"

"Memorable."

She snorted derisively, another hint that something was wrong in our relationship.

"'Tis all a mistake," she sighted, cruling up against me.

"Our sleeping together?"

"No…ourselves going to Ireland."

It was the first hint that she didn't think our trip was a frigging brilliant idea—to use her slightly cleaned up words.

"Why?"

"Bad things are happening," she said, cuddling even closer—as much as a first-class set on an Aer Lingus Airbus 300 permitted.

"To us?"

"Won't we be involved?"

"The Irish media?"

"Them gobshites!"

My hand, always with a mind of its own where she was concerned, found its way under her loose Marquette University sweatshirt and took possession of a wondrous bare breast. Bars, she had insisted, were not acceptable on long overnight plane flights, a declaration I did not dispute.

She sighed contentedly.

"Anyway," she continued, "the woman didn't do it now, did she?"

"Didn't do what?"

"Didn't light the fire."

"Which woman didn't light what fire?"

"Och, Dermot Michael," she said somewhat impatiently as, under her blanket, she pushed my hand harder against her breast, "if I were knowing that, wouldn't I be telling you?"

Here we go again, I told myself.

We were at that stage of transatlantic flight that is much like the old Catholic notion of Purgatory—the minutes seem like hours and the hours like days. The human organism revolts against all the indignities imposed on it in the last seven hours—dry mouth, wet sinuses, aching teeth, the guy across the aisle with a cough like a broaching whale. It will end eventually but only on the day of the final judgment.

My Nuala Anne is, among other things, fey, psychic, a dark one—call it whatever you want. She possesses, though only intermittently, an ability to see and hear things that happened decades ago or are happening now but at some great distance or haven't happened yet but will. Maybe. My brother George the priest, the only other one in our family to know of my bride's "interludes," claims that her ability is a throwback to an earlier age of the evolutionary process when our hominoid ancestors, nor possessing thoraxes suitable for our kind of speech, communicated mentally.

"There're a few genes likes that around, Little Bro," he informed me, "but don't invest in any grain futures because of what she thinks she sees."

I had stopped investing in the commodities market several years ago, mostly because I wasn't very good at it.

"It's weird, George," I had argued.

"Part of the package," he said with a shrug.

Easy enough for him to say. He didn't have to live with her. Nor was he awakened in the middle of the night when she had one of her dreams.

She sat up straight in her seat, dislodging my predatory hand.

"They're going to shoot the poor man, Dermot Michael," she whispered, "and himself going to Mass!"

Fortunately, the man across the aisle hacked again, so violently that I thought the plane swayed. His explosion drowned Nuala's protest.

"Can we do anything?" I asked ineptly.

"Course not," she replied impatiently. "And ourselves up here in this friggin' airplane!"

We were getting into trouble again. Whenever my wife had one of her intense spells, it was a sign that we were stumbling towards another strange adventure. Like the time at Mount Carmel Cemetery when she saw that the grave next to my grandparents' plot was empty1 or the incident on Lake Shore Drive when she heard Confederate prisoners crying out in pain in pain in Camp Douglas at 31st and Cottage Grove—in 1864!

Won't the woman be the death of ya? the Adversary whispered in my brain.

"Go 'way." I told him. "That's part of the package. Besides, your brogue is phony."

Nuala Anne is quite a package. She's the kind of woman even women turn around to look at when she walks down the street. She looks like a mythological Irish goddess, though I've never seen one of those worthies. They travel in threes, I'm told. Nuala is all three of them.

Drawings of the Celtic women deities, however, hint that they have solemn, frozen, slightly dyspeptic faces, as if they are so displeased with mortals that they will not deign to notice our existence. Nuala's lovely face with its fine bones and deep blue eyes is in constant movement as emotions chase one another across it like greyhounds headed for the finish line—amusement, mischief, anger, sorrow, hauteur, devilment, fragility, sorrow. Each emotion represents one of the many different women in her complex personality: Nuala the detective, Nuala the woman leprechaun, Nuala the accountant, Nuala the athlete, Nuala the actress, Nuala the singer, Nuala the seducer, Nuala the vulnerable child.

I'm usually one step behind the most recent greyhound as I struggle to keep up with the rapid succession of personae. Her deep blue eyes can shift from tundra to Lake Michigan on the hottest day of the summer in the flick of a lash. And back. Heaven help me if I miss the flick.

She is tall and slender, with long and muscular legs and elegant breasts. Here is a model's body, a model for athletic wear. She looks great in an evening gown with spaghetti straps but even more striking in tennis shirt and shorts. What she looks like with her clothes off is my business and no one else's—save that her beauty breaks my heart.

There is an ur-Nuala, I think. Her mask is that of the shy, quiet Irish-speaking country girl from Carraroe (An Cheathru Rua in her native Irish) in the Connemara district of the Country Galway. I love all the Nualas, but I love that one the most.

However, I also love her hopelessly when she's busy making trouble . Like the day when she showed for the little bishop's Mass on the dunes at Grand Beach with a red T-shirt that proclaimed in large black letters: "Galway Hooker!"

The little bishop, George the Priest's boss, was unfazed.

"Have you ever crewed in one of the boat races, Nuala Anne?" he asked. "Am I not correct that the word is based on the Duch houkah, which means 'boat with a long prow'?"

I had not seen that mischievous troublemaker for a long time. Nuala Anne was upset that she was not pregnant. Moreover, for reasons that I could not fathom, she was convinced that she was not a good wife. Unshakably convinced.

The pilot announced that we were an hour from Dublin Airport.

"I suppose I should put on me bra," she sighed, stirring next to me.

"If you want to."

"If I don't, it will just give them friggin' bitches in the friggin' media something to bitch about, won't it now."

Nuala's first CD, Nuala Anne, had been a huge success, not bad for a young woman not yet twenty-one. She has a lovely voice, trained first by her mother in their tiny cottage in Galway, then by a teacher at Trinity College, where Nuala had studied accounting , and finally by "Madam," a legendary voice coach in Chicago. The last named had told us that Nuala was a first rate talent for the pop world, though she would never be an operatic singer. That was fine with both of us.

"Meself a friggin' diva!" she had exclaimed, as though it were a huge joke.

Her beauty, her charm, her acting ability, and her skill with an Irish harp contributed to her success. She had made the leap from Chicago pubs quickly, too quickly for the media in her native land. One Irish woman writer commented, "Don't we have too many pretty young Irish singers as it is without an American one trying to join the lot?"

This bit of envy ignored the fact that Nuala had lived in the United States for only a year wheb the first disk appeared.

The second disk was not supposed to be a hit. She insisted that she wanted to record hymns. The recording company grudgingly gave in.Nuala Anne Goes to Church was a combination of pre-Vatican Council hymns(like the May-crowning hymn "Bring Flowers of the Rarest"), spirituals such as "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," a few Protestant hymns like "Simple Gifts" and "Amazing Grace," and some Irish-language religious music. There was nothing very new or very original on it, save for her voice and her devotion. The result was that the disk was a bigger hit that its predecessor, in both Ireland and the United Stated. The Irish critics were furious. How dare someone just out of Trinity become a celebrity so soon and so easily! Their envy, however, did not prevent Irish International Aid, an Irish social action agency, from inviting her to perform at a benefit concert at the Point Theater on the banks of the River Liffey (where Riverdance first appeared).

Naturally, Nuala did not hesitate. Nor did she show the slightest signs of backing off when the Irish papers attacked the concert as soon as it was announced. My Nuala never saw a fight she didn't like.

I thought the whole idea was crazy, but being a wise husband (in some matters anyway), I kept my mouth shut.

I looked around the first-class cabin (my idea)as she walked towards the washroom. The two other people in first class were sound asleep, as were the cabin attendants. So I followed her.

"What would you be wanting?" she demanded, her face turned away demurely as I pushed in after her.

"To hook your bra, like I always do."

"All right," she sighed as she pulled the Marquette sweatshirt over her head.

I caught my breath, as I always did when I saw her naked to the waist. Making the process as long and leisurely as I could, I assisted her with her black lace bra. She sighed contentedly.

"Are you going to put your sweatshirt back on?" I asked when I had the last hook in place.

"Would it be fun if I walked into the cabin without it?"

"Be my guest!"

She snorted, tied her hair up, and donned again the maroon and gold of Marquette.

I had attended Marquette for two years after I was expelled—for academic reasons—from Notre Dame. However, I had not graduated from Marquette, or anywhere else.

"I thought you might try to fuck me in there, Dermot love," she said as we slipped back through the aisle to our seats.

"Would you have liked that?"

"Wouldn't it have been an interesting experience now?"

Blew it again, the Adversary crowed.

Suddenly Nuala stiffened in front of me and then collapsed into my arms.

"It's so hot, Dermot Michael. Call the fire battalion before we all perish with the heat."

Gently I guided her to our seats.

"Terrible, terrible hot. We're all burning up. Our lungs are filled with smoke."

Then she began to sob softly.

"Is your wife all right, Mr. Coyne?" a cabin attendant asked.

"Bad dream,"

"It's not a dream," Nuala insisted when the young woman had returned to the small kitchen where she was preparing breakfast. "It's really happening."

|"It's all right, Nuala Anne," I insisted. "It's all right."

Gradually her sobs subsided.

Shot on the way to Mass. Something like that had really happened in Irish history. Who was it? And when? Lord Edward FitzGerald?

I'd call George from Dublin. He knew everything.

"Haven't you married a crazy women, Dermot?" she said with a sniffle.

"No," I said. "I married the finest wife in all the world."

She snorted again, as if to say. Thanks for the compliment, but you and I know better."

Actually, I didn't know better. She was indeed a wonderful wife, fun to be with, glories in bed, undemanding, eager to please me. Too eager. When I complained that she slammed doors and pounded through the apartment like a herd of horses and slammed doors like a security guard, she apologized and walked on tiptoes—making me feel like a heel. I had also protested when she turned her compulsive neatness loose on my desk. "I can't find a thing," I growled. Tears sprang to her eyes as she apologized.

It wasn't that big a deal.

Something was wrong, badly wrong, but I didn't know what it was.

You're a lousy husband and a worse lover, the Adversary sneered.

I didn't answered because I was afraid he might be right.

Yet she certainly seemed satisfied with our lovemaking. She praised my skills in bed. I was the greatest lover in all the world, she insisted—which I knew I wasn't.

I tried to talk about what our problem might be, and she dismissed me brusquely: "How could anyone have a problem with such a wonderful lover as you, Dermot Micheal?"

Yeah.

They served us our continental breakfast.

"Haven't I become so much a Yank," she said, "that I want a much bigger breakfast?"

"Are you a Yank or Mick when the media ask you?"

"Wont I have a good answer for them now?"

"Which meant that she wanted to surprise me, too. Nuala played very few situations by ear. She doubtless had all the answers ready for the catechism that would greet her as soon as we walked out of customs.

"We are now crossing the coast of Ireland just above Galway," the pilot announced. "You can see Galway Bay through the clouds."

Her fey interlude forgotten, she climbed over me to look out the window.

"Och, sure, Dermont Michael, isn't it the most beautiful place in all the world? Isn't the green brilliant altogether?"

She arranged herself on my lap, a posture I was not about to protest.

"It comes from all the rain."

"Shush, Dermot love. It's me home, even if it is a mite

damp…OH! Isn't that Carraroe down there?"

We had not visited Ireland on our honeymoon. "Haven't I seen everything there is to see?" she had said, waving her hand in a dismissive gesture that meant only an eejit would suggest such an absurd nation.

"'Tis," I said even though I couldn't see.

"Isn't it the first time I've seen it from the air…Oh, Dermot Michael, isn't it lovely?"

She wept again, this time at the joy of a brief glimpse of her little village from the air, the village that had been her world before she had left for Trinity College only a couple of years before.

"We should have come back here long ago!" she added.

Being, like I said, a sometimes-wise husband, I did not observe that I had proposed it as a honeymoon stop.

"I can hardly wait to see me ma and me da…Och, Dermot, there's a great sadness on me!"

More tears. I put my arm around her, eased her back into her seat, and held her close.

"Well," she murmured, "at least I'm glad you're along to take care of me on this focking trip to this focking country."

A change of mind? Not at all, not among a people for whom the principle of contradiction does not apply.

"Haven't you been taking care of me," I replied, having learned the proper responses in seven months of marriage, "since we were married?"

"Go 'long wid ya!" she said, patting my arm in approval.

Mostly she had taken care of me. At least she organized everything, though she was always wary for the slightest sign that I might disapprove of her plans for anything from a movie to the furniture for our home across the street from St. Josaphat on Southern Avenue. She also decided that we'd be wise to keep our apartment at the John Hancock Center because it would always be a solid investment. Besides, she liked the swimming pool there better than the one at the East Bank Club.

"More privacy. if you take me meaning, Dermont Micheal."

I did not disagree.

Her meaning was that we could return to the apartment and make love with less delay than if we had to drive from the East Bank back to DePaul(as our neighborhood, also known as Lincoln Park West, was called).

She also took charge of my investments. This meant that she talked to the broker and commodity trader who presided over my ill-gotten grains from the Mercantile Exchange and the profits from my novel—as well as, in a separate account naturally "so there won't be any confusion," the royalties from her recordings.

"Sure, aren't you a poet and meself just a focking accountant?"

Who was I to argue with that wisdom, especially when the trader whispered into my ear that I had one very shrewd wife.

Sure, hadn't I known that all along?

I am often referred to by the women in my family as "poor Dermot." That does not mean impoverished or suffering. Rather, it means that Dermot is a nice boy; isn't it too bad he doesn't have a clue?

About what?

About anything.

Or as one young women not the family had said at a black-tie dinner in the Chicago Hilton and Towers, "Yeah, he's a handsome hunk and kind of sweet in a dull way, but he's useless. He'll live off her for the rest of his life."

I was forced to constrain Nuala from tearing out the eyes of the aforementioned young women.

"Sure, aren't you a great novelist and poet!" she had whispered fiercely before I pulled her into a corner of the massive lobby of that gargantuan hostelry.

"And a brilliant commodity trader, too!"

Her humor returned. "Well, I didn't say that exactly, did I now?"

The pilot announced that we were approaching Dublin Airport. Below us the bright green fields, a jeweler's display of emeralds, glowed in the soft light of the rising sun.

"It looks like God has swept away the Irish mists to celebrate your return," I said to my wife.

"Do you return think He has?" she said, clutching my arm more tightly.

"She," I corrected her.

"'Tis true." She dabbed at her eyes with a tissue.

Another knock on me is that I'm lazy. It's true that I don't work very much, but the objection is aimed at the face that I don't have a regular office or even a regular job. The youngest of a family of hot-shot professionals, I am viewed as a kind of spoiled baby who sits around and does very little. I get no points for having written a novel that was on the Times(New York' that is) best-seller list for fifteen weeks in hardbound (and was now on in its paperback manifestation). The occupational category of "writer," to say nothing of "poet," is not altogether acceptable in River Forest, Illinois. Moreover, to make matters worse, there is no visible evidence that when I starting writing I work very hard at it.

I had done practically nothing since our marriage except scratch out a poem or two and develop (mentally) an outline for another novel for which I had a contract. Nuala had worked frantically on her voice lessons and her recordings while I had devoted myself mostly to enjoying her—a delightful full-time occupation. Moreover, I had engaged in this enterprise without putting on weight, as most young men of my generation do in the months after their marriage. Admittedly, Nuala Anne had shamed me into it by her good example.

Besides, running with her or swimming or working out together was part of the fun. She was fun in bed and fun in every other aspect of our life together, fun and funny, outrageous, contradictory, unpredictable, zany. Spouses, I have been told, often grow weary of each other. I could not imagine Nuala Anne ever boring me.

You're a sensualist on a sustained orgy, the Adversary had informed me before he got on my case as a lousy lover.

"Yeah,"I replied without the slightest feeling of guilt.

There were some problems in our marriage, clouds on the edge of paradise.

My wife was afraid of me. Though she played the role of organizer and administrator of our joint fun and fortune, it was always with a shadow of worry in her blue eyes, as if I were a drunken wife beater.

"I am not an ogre," I said to the little bishop.

I go to George the Priest when I want facts—such as who was the Irish leader shot on the way to Mass. I go to George's boss when I want advice.

"Indeed," that worthy had commented.

"Yet she's habitually afraid that she'll offend me."

"Adoration," he said with a loud sigh.

"I am not adorable."

"Arguably…Yet she began to adore you on that now legendary night you met at O'Neill's pub. Nothing that has transpired since has caused her to change her opinion."

"Will she get over it?"

"She will perhaps adjust to it."

That was bad enough. More recently I thought I detected an even darker cloud. Nuala had begun to suggest that she was half-convinced that she was not half good enough a wife.

"Does that make 25 percent?" I had asked the little bishop.

"More like 200 percent."

The Airbus touched lightly down on the green fields of Ireland. Nuala applauded enthusiastically, not because she doubted a safe landing but because she was on Irish soil again.

I had tried to discuss this strange notion with her, but she ruled me out of order.

"A lot you know, Dermot Michael Coyne, about what's a good wife."

Finally, she was worried about not being pregnant. Our plan—well, her plan—was that we'd have our children (arguably, as the bishop would say), three of them, before she was twenty-six, so our nest would be empty by the time she was in her earlier forties. The first would be a girl with red hair and green eyes who would be called Mary Anne (Nell after my grandmother, with whom Nuala has some sort of mildly scary psychic relationship).

Who was I to disagree?

However, the first pregnancy was not happening according to plan.

"On the average it takes seventy-five acts of intercourse to produce a conception," I observed, quoting, though hardly by name, George the Priest.

"Och, Dermot Michael, haven't we done it more often than that?" she somberly.

Who's courting?

Nuala Anne, obviously.

I was sure she had consulted with my mother, who is a nurse, and that Mom had reassured her. Not that it had done any good.

So my Nuala had gradually become more pensive, more preoccupied, more obviously thoughtful, and less the exuberant organizer and imp than she had been only a month or two before our trip to Ireland. I had no idea what to do.

You're a failure as a lover and a husband, the Adversary insisted.

"Shut up," I told him.

I was confident on neither subject. I remembered the South America novelist who said that after thirty years of marriage he knew his wife better than anyone else in the world and knew that he would understand her. What did I know about the complex puzzles did I know about a women's orgasms? The woman from River Forest who had seduced me and then dropped me when I refused to go to work for her father had done a lot of screaming, but, looking back on it, I doubted that she had know any more about sexual abandon than I did. Nuala insisted that I was a wonderful lover and adamantly refused to proceed beyond that assertion.

I half-believed that she was half telling the truth.

The purser, in a brogue as thick as Nuala's explained about immigration and customs as the plane taxied to the terminal.

"Well," said herself, "I'll have to get ready for them nine-fingered shite hawks, won't I now?"

"Won't you have to get ready to cream them?"

I had learned from a book that when the Irish answer a question by asking a question they are following in English a form adopted from the Irish language that adds emphasis to what has been said. Sometimes. Also, the world self added to a pronoun is a trace of the original melody in the language the English had stamped out—though I every immigrant group before Cromwell had adopted Irish as their own tongue.

Nuala Anne sighed loudly.

The plane finally snuggled with relief against its jet bridge. Since we were in first class, there was less of the gang fight for the recovery of baggage from the compartments above our seats than there usually is. I was grateful for that. Once, on our honeymoon, a very pushy matron of uncertain nationality had shoved me aside to retrieve a large bag and then, having jerked it out of the compartment, bounced it off my head. I collapsed into a handy seat and thus cleared the way for Nuala Anne to charge after the woman, shake her fiercely, and threaten that if she ever dared to hit her husband again, she would kill her. The terrified perpetrator, not understanding a world but knowing she was in deep trouble, fled for her life. Two cabin attendants who had watched the contretemps in horror rushed to my aid. Having assured themselves that I would probably survive, they awarded us two bottles of champagne.

"Nuala," I had said as we left the plane, "that woman didn't understand a world you said."

"Ah," me, er, my beloved beamed, "didn't she get the point now?"

As we were leaving the plane in Dublin, one of the cabin attendants grasped Nuala's hand.

"Och, Nuala Anne, I love your songs. Have a grand concert over at the Point."

Point in Irish English is pronounced as if it were the same thing from which one consumes a half-quart of Guinness.

Nuala stuck out her hand in my direction. I reached into the Aer Lingus flight bag I carried and produced a CD. She signed it with a flourish and presented it to the delighted cabin attendant.

Ah, you say, isn't Dermot Michael Coyne a nice young man? Doesn't he carry around copies of his wife's recording so she can give them to people?

And doesn't he do it because the wife has asked him to , very politely and timidly of course?

In the arrivals hall, a small girl child with red hair rushed up and embraced Nuala's calf—a not infrequent reaction of children when they see her.

Herself lifted the delighted rug rat high into the air. "Sure, don't I want one just like you," she said with an enormous smile. "But I think I'll let your parents keep you."

The parents knew who she was and smiled proudly. produced another CD and Nuala autographed it for "Ciara with the bright green eyes!"

We recovered our vast pile of luggage—you can't go on a concert tour without many changes of costumes, even if it's only a one-concert tour. Nuala took charge of her guitar and the small Celtic harp I had bought her when she came to America. I piled the rest on a cart.

"And meself coming to Dublin for the first time," she murmured disapprovingly, "with only one small bag."

"Same wonderful young woman," I argued.

Again she snorted derisively.

"Nuala Anne," I said as we entered the green customs gate, "what's a nine-fingered shite hawk?"

"A journalist," she said grimly.

God help them.

Copyright © 1999 by Andrew M. Greeley Enterprises, Ltd.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...