- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

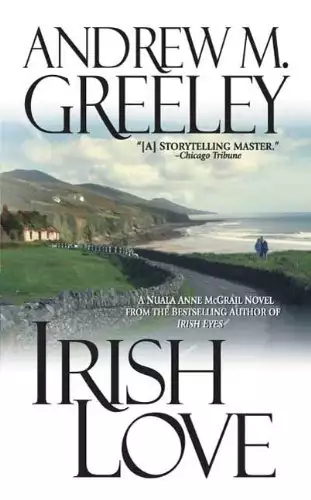

Continuing the enchanting chronicles of the fabulous Nuala Anne McGrail and her spear-carrying husband Dermot, bestselling author Andrew M. Greeley takes them once again to Ireland for another thrill-packed adventure.

Back on the Emerald Isle, Nuala and Dermot soon get the feeling that someone is out to get them. They find themselves dodging multiple explosions, and someone starts shooting at Nuala while she is water-skiing in the cold Atlantic. Meanwhile, the handsome parish priest, Father Jack, has given Dermot the diary of a young Chicago newspaperman. Written in the year 1882, the diary tells in horrendous detail an intriguing story of a mass murder and a trumped-up trial in which one of Ireland's greatest heroes was accused of the murders without a shred of evidence. These two stories, ancient and modern, soon get mixed up, and they make for an utterly fascinating tale of murder, betrayal, and redemption with Nuala and her magical powers at the center of it all. Andrew Greeley not only tells us a riveting tale of adventure and derring-do, he gives us a picture of modern-day prosperous Ireland and the engaging and, of course, sometimes villainous people who live there.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: March 15, 2002

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Irish Love

Andrew M. Greeley

1

"BLOOD!" MY wife announced. "There's blood everywhere."

"This is a bad place, Da." The pretty redhead dug her fingers into my arm. "I wanna go home!"

Our beautiful Connemara day had suddenly turned somber. Dank fog had drifted in, Kilray Harbor and Galway Bay had disappeared; the ruined hovels my wife had been photographing had quickly changed from picturesque to desolate--and perhaps sinister. The ugly slabs of rock on which we were standing seemed somehow sinister, like the basement of a haunted house. With the fog had come a sudden blast of cold air. Despite my Aran Isle sweater, I shivered. We were in a horror film.

In my arms the Mick, big, blond, and lazy--like his father it was often said--continued to sleep contentedly, his usual mode of facing life.

I glanced around. The three females in our party were sniffing the air. I sniffed too. All I could smell was the acrid salt of seawater.

Nuala Anne was wearing the young matron's uniform: jeans, running shoes, and a sweatshirt, in this case a blue-and-gold sweatshirt from Marquette University.

"It smells!" The little redhead, my three-year-old daughter, Nelliecoyne, wrinkled her pert little nose. "I wanna go home now."

She was dressed as her mother was, though neither had ever seen Marquette, where I spent my last years of college (and failed to graduate). Like her mother, she wore a blue-and-gold ribbon around her hair.

There was patently not blood everywhere. However, my wife and daughter are fey. If they smelled blood, then there had been blood there once. Moreover, by the time we returned down the mountains to our bungalow in Renvyle it would be our family duty to find out why they smelled blood. I sighed, not as loudly or agonizingly as the locals sigh, but still vigorously for a friggin' Yank. This we did not need.

The third female in our party, Fiona, our snow white and presumably pregnant wolfhound, stuck her massive snout skyward and, falling back on her wolf ancestors, howled in protest.

I had not thought that Fiona was fey.

"I wonder who the last people who lived in this place were," Nuala Anne had said before the dark and icy pall had descended upon us. "And where they went."

"Probably to America," I said lightly, "where their descendants are now rich, complacent, overweight, and Republican."

I wondered how anyone could have possibly spent their whole life in a cave with a stone extension, or in a tiny hut not much bigger than a closet in our home on Southport Avenue across from St. Josaphat's Church. Yet, at one time, the hut was home to three or four impoverished, illiterate families clinging to life on the hard rocks of County Galway. The roof and walls had collapsed, a few rotting timbers lay on the ground, a straggly blackthorn tree stood by, a dubious memorial. All that remained were a few piles of rubble. In another decade there would benothing left. Yet, in Ma's time--my grandmother Nell Pat Malone that was--people would have remembered who had lived in this little cemetery and her father, Paddy Tom Malone, might have known them.

It was while I was pondering the melancholy scene--melancholy comes easy in the West of Ireland--that the pall of fog covered us. With the fog had come the stench. Had Nuala's question about the inhabitants of this harsh little place called both the fog and the smell?

It wouldn't have been the first time something like that happened.

My daughter deserted me and ran to cling to her mother's jean-covered leg. I walked bravely toward the largest hut. Fiona trailed after me, growling softly. Yet, she didn't try to stop me. Neither did my wife or daughter. As for my son, he continued to sleep, oblivious to the smell and to the wolfhound's howl.

Bravely, I walked into the shell of stone remnants. Fiona doggedly (you should excuse the expression) trailed behind me, growling at whatever was inside. I didn't expect to find anything. Nevertheless, every contact of my wife with the uncanny tempted me to believe that she saw more deeply into reality than I could ever hope to.

"There's nothing here!" I announced bravely.

Fiona barked happily and nudged me in approval.

The sun, perhaps reassured, promptly returned. The fog dissipated. The temperature climbed back into the seventies--perishing with the heat in this rocky, rainy island.

"Daddy made the bad smell go away," Nelliecoyne announced proudly.

"Isn't Daddy a brilliant exorcist?" my wife agreed. "Brilliant altogether?"

She was pale and tense, her Mavica camera hanging loosely on her arm.

DERMOT MICHAEL AN EXORCIST! said the Adversary,a voice hidden in the back of my head that frequently comments on my follies.

"Maybe we had better go home," I said gently.

"I think you have the right of it, Dermot Michael," Nuala agreed. "Enough of me picture-taking for this morning."

We were on the lip of a valley created by the Twelve Bens mountain chain. On the north was the Atlantic Ocean, and on the south stretched the valley, a picturesque, if barren and rocky, slice of land carved out by the Traheen River rushing among the mountains in a frantic search for the sea. Like most of the land in Connemara, the valley was brown even in late spring, save for the dark gash of the river, its grasslands stripped by generations of grazing sheep. Connemara had once been almost as green as Wicklow, over near Dublin. But the fierce struggle of the local people for life had denuded it of its trees and then its grasslands.

A few whitewashed stone houses dotted the sides of the valley, homes of the shepherds whose EU-funded sheep grazed the valley floor and hillsides, nibbling on the sparse meadows.

"Diamond Hill" Nuala had called it as we reached the top of the mountain. "See that manor house down there on the hill? Hasn't some fancy English lord restored it?"

It was a Big House in the sense of the English Protestant Ascendancy of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but it was not particularly large compared to some of the great manors--a relatively small manifestation of Georgian culture, planted precariously in the midst of another, much older and more opaque, culture.

The latter might well have been called, up until the end of the last century, Neolithic.

"I imagine the locals don't like the fella very much?"

Nuala had shrugged indifferently. "Don't they say he'sa nice man and really Irish? He's not oppressing anyone, is he?"

Nuala had given up singing over a year ago and was now painting wild scenes from the Irish countryside. Since she didn't want anyone to see her watercolors, she would explore the countryside, photograph the sites, then return to the privacy of our home and paint with frantic haste.

Home was not our house on Southport Avenue in Chicago, right across the street from St. Josaphat's Church. Nor was it our summer place in Grand Beach, Michigan. Rather it was a bungalow in Renvyle on the far coast of Connemara, a place the next parish to which is on Long Island, as the locals say. Renvyle, by the way, means "bare headland" in Irish, a grimly accurate description.

"Grand," I said, as I removed our son from my arms and put him in the sack around my wife's neck. Then I picked up his sister.

"Let me sit on your head, Daddy," Nelliecoyne pleaded.

"You're too heavy," I replied.

"I am NOT!"

We began to carefully pick our way down the mountain trail to the main road through Letterfrack National Park.

We had covered the first half of our ten-minute walk back to our Ford before Nuala Anne said a word.

"Wouldn't you think this psychic stuff is getting tiresome, Dermot Michael?"

"It's not your fault," I said, repeating what had become my favorite mantra for the last year and a half.

"Still and all, I'm an educated, modern woman. I know that this psychic shite is all nonsense, isn't it now?"

I sighed as only someone from the West of Ireland--by adoption at least--can sigh.

"I'm not one of your superstitious Irish peasants, am I?"

My wife was indeed an educated, modern woman--Trinity College degree. She was also, if not exactly a superstitious peasant, a throwback to the Neolithic age.

"I thought it would all go away after I had this little gosson. Didn't me ma say that me Aunt Aggie, you know, the one in New Zealand, stopped seeing things after her second child was born?"

"Ah?"

I had never heard of Aunt Aggie before.

"And wasn't she the one who passed on the second sight to me? Isn't it always from aunt to niece, like me ma says?"

"That doesn't explain why Nelliecoyne is even more fey than you are."

She sighed, as if showing me how it should be done.

"'Tis true."

"Daddy made the bad smell go away," that worthy little elf proclaimed from atop my head.

"Sure, darlin', there wasn't any bad smell. Wasn't it only the fog?"

Our daughter did not deign to debate that point.

Nuala began to hum the Connemara Cradle Song to her son, the first hint of music I had heard since his birth.

On the wings of the wind, o'er the dark, rolling deep,

Angels are coming to watch o'er your sleep.

Angels are coming to watch over you.

So list to the wind coming over the sea.

Hear the wind blow, hear the wind blow,

Lean your head over, hear the wind blow.

"Still, it was women's blood up there, wasn't it, Fiona darlin'?"

The wolfhound barked in approval as she always did when Nuala spoke her name.

"Women's blood?"

"Grandmother, mother, and daughter, all were murdered up there."

"They were?"

She nodded solemnly.

"And didn't the poor woman lose her husband over it?"

"One of those who died?"

"Och, Dermot Michael, don't be an eejit! They were already dead. It was the other woman."

"Oh."

When we reached our van, my son (whose real name is Micheal Dermod, pronounced MI-hall DIR-mud) emitted a small complaining sound, which usually meant that he wanted his diaper changed. Nuala promptly took over the task while Fiona, accompanied by Nelliecoyne clinging to her collar, sniffed round the parking area just to make sure that no other canines had invaded this sanctuary while we were up on the mountain.

When our daughter was in the diaper stage, I was frequently permitted to change her diaper. Nuala reserved changes for the Mick to herself.

"Poor dear little thing," she murmured, holding him close after she had reassembled his clothes.

On the lips of an Irish woman the word "poor" in that context ordinarily did not indicate either spiritual or material poverty. Rather it represented the superlative of the following adjective as in "dearest little thing." (Or "ting" since the Gaelic lacks an "h" sound.)

My wife was convinced that during her bout of postpartum depression she had neglected the Mick, and she was now trying to make up for it.

I was sure that behind my back she was calling me "poor dear Dermot and himself having to put up with a terrible wife like me."

"Your wife has always excelled, has she not, Mr.Coyne?" the psychiatrist, a handsome Jewish grandmother had said to me. "At everything?"

"Sports, singing, acting, lovemaking," I had agreed.

"Often by sheer willpower?"

"And raw talent."

"And she comes from a cultural background where there are no great demands for a woman to be good at everything all the time?"

"It's changing over there, but in her community that's still true."

"And now she believes that she's a bad wife and a bad mother and a worthless human being?"

"She cries all the time and loses her temper and then cries some more. She complains that I don't help her with the children and then shouts at me when I do help. She has to do it all herself because no one else knows how to do it right."

"But you did persuade her to see me?"

"Her own mother did, at my instigation. 'Me ma says I should see the doctor person.'"

The psychiatrist smiled thinly.

"She's overwhelmed, Mr. Coyne, by her own internalized demands and by the demands of our culture. Let me read you a quote from Dr. Thurer. 'The current standards for good mothering are so formidable, self-denying, elusive, changeable, and contradictory that they are unattainable. Our contemporary myth heaps upon the mother so many duties and expectations that to take it seriously would be hazardous to her mental health.' Your wife takes the myth very seriously indeed. Her saving grace is that in her better moments she laughs at it."

"She'll be all right?"

"Yes, of course, eventually. It may require several months, and she must take her medicine every day ... . A woman's body undergoes hormonal changes constantly. There are enormous changes after she gives birth. Whenthis is combined with a strong sense of personal responsibility, such as your wife possesses ..."

"Is possessed by."

"Exactly ... You understand the problem. Have her moods affected your son, do you think?"

"The Mick? A seven-forty-seven could crash outside our house and he would hardly notice ... . Nuala Anne says that he's like his father."

"I doubt that she really means that," the doctor had said with another thin smile. "However, you must accept for the present her insistence that she is giving up her career. Eventually she may change her mind, but she must change it for herself."

"Naturally."

"When I told her that this kind of problem happens after ten percent of births, she seemed relieved."

"Oh?"

"Her exact words"--third thin smile--"were that she wasn't the only friggin' fruitcake in the world."

Later, as we were driving home from the "doctor woman's office," Nuala complained, "Dermot Michael, a woman is nothin' but a friggin' cesspool of friggin' hormones."

Despite myself I started to laugh. For a moment she pretended to be upset with me, then she laughed too.

There was another crisis over her medication. She didn't want to poison her "poor little tyke" and she didn't want to give up breast-feeding. Her mother, the good Annie McGrail, had persuaded her that it was more important for her son to have a happy mother than to drink her milk.

However, she often felt that since she was "better now" that it would be a sign of weakness to take her medication every day.

"Woman," I had thundered at her, "the doctor woman said you had to take it every day until she said you couldstop. So you swallow the thing in me presence or I'll divorce you."

(The Gaelic lacks the possessive pronoun. Often, and despite heroic efforts, I slip into her idiom.)

"Och, sure, Dermot love, don't you have the right of it?" she had said, collapsing into my arms in tears. "I promise."

YOU'D NEVER DIVORCE HER.

So now she has indeed swallowed the medicine in my presence daily with a great show of phony obedience.

"She knows I'd never divorce her."

We arranged our offspring in their car seats. Fiona jumped into the rear seat of the van, rocking it with her hundred-and-forty-pound mass, and curled up for her nap. Nelliecoyne started telling stories to her gurgling and cooing little brother in Irish. Nuala began to drive down the narrow road that circles the Letterfrack National Park in the Ballynahinch mountains.

AT LEAST SHE'S SINGING AGAIN.

"Humming." I replied to the Adversary. Besides, she's fey again too.

NOTHING I CAN DO ABOUT THAT. YOU KNEW WHAT YOU WERE GETTING INTO WHEN YOU MARRIED HER. ISN'T SHE ONE OF THE DARK ONES?

"I'd be glad to have her fey, if it means that she's singing again."

Did me wife, oops, my wife really believe that the difficulties of her two pregnancies (on the flat of her back for the last three months before the Mick arrived) and two very arduous deliveries and then the depression were her fault? Were they proof that she was indeed a poor wife and mother?

You can live with a woman for five years, pleasurably enough, and realize that you know less about her than you did on your wedding day. My guess is that, in the opaque Irish idiom, she "half believed it." As best as I can understandthe idiom, it does not mean half and half, but rather, totally some of the time and not at all, at all the rest of the time. Sometimes she thought she was a total failure, and other times she thought, correctly, that despite the depression she was a total success as a wife and mother.

The latter, of course, was the truth.

Letterfrack was swarming with Yank tourists shopping at the "Irish Crafts" store, which the Protestants had founded long ago in their totally unsuccessful efforts to win the locals away from their popish superstitions. At the edge of the town we heard a distant explosion and saw a puff of black smoke, a dirty hand that hung as if suspended against the pure blue sky.

"Is it a bomb now, Dermot Michael?" Nuala gasped.

"It looks like it is."

"In Renvyle, do you think?"

"Maybe."

"Och ... I hope it's not our house!"

"There's no one in it, and it's insured."

Which was a characteristically stupid male response.

"Didn't the lads set off a bomb?" Nelliecoyne commented and then went back to her Irish babble.

"The lads" was an Irish euphemism--they are a people who love euphemisms--for the Irish Republican Army. After the Northern Ireland peace agreement, most of the lads had turned to more peaceful tasks.

"She did say that, didn't she?" I asked in a whisper, suppressing a shiver.

"It's probably something she heard us say when there was a loud noise," Nuala replied with little conviction.

When we reached the coast road, where the sapphire Atlantic brushed easily against the shoreline, leaving a thick white lace of foam, the cloud had faded to a smirch, a telltale hint of evil on the azure sky.

We were about a mile (Galwegians don't hold withkilometers) from our cottage in the shadow of Renvyle House Hotel, when a smartly dressed young Garda flagged us down.

"Papers, please," she said briskly. You didn't ask this brisk young woman about a bomb until you had identified yourself.

"Dermot?"

I searched my pockets as if I thought I really had them.

"Must have left the passports at home."

"Driver's license?" The constable frowned disapprovingly. I was patently a typically stupid Yank.

Nuala produced her license and spoke in Irish doubtless telling the pretty blond constable that her husband was an eejit altogether. I always assumed that when she went into her first language she was talking about me--and not paying me any compliments.

THE NAME OF THAT, BOYO, IS PARANOIA.

"You have the Irish," the Garda said, "but this is a Yank driver's license ... . Oh my, who are you?"

A massive white snout had appeared between our two children and then a vast mouth with a wide grin.

"Isn't it Fiona?" I said. "And herself a retired member of the Gardai. Whenever she encounters a colleague she wants to make friends!"

I got out of the van and opened the door. Delighted, Fiona bounded out, circled the van in an enthusiastic rush, and placed her two massive paws on the young woman's shoulders and licked her face. She was at least a foot taller than the constable.

"Oh, aren't you a great beauty now!" The officer hugged her newfound friend. "Sure, you'll smother me completely!"

She said a word in Irish. Our wolfhound sat down, her tail wagging furiously.

"Haven't we bred her with Sir Roy Harcourt de Bourkthe fourth?" Nuala explained. "And don't we think she's pregnant?"

"I bet she gave him a hard time!"

Even when the female is in heat, wolfhounds would rather chase each other around and play than engage in sexual intercourse. Finally, the breeders had to constrain them to do so by a method that I will not describe.

"Isn't she an Irish female?" I said.

"Dermot Michael!" my wife shouted in protest.

"She's going to have three puppies," my daughter informed the Garda.

"Is she now? And what's your name?"

"Moire Ain Coyne," the redhead announced proudly.

"The problem, Ms. Coyne," the Garda said as she patted the head of the ecstatic Fiona, "is that there was an explosion down the road."

"Didn't the lads set off a bomb?" Moire Ain Coyne informed her.

The Garda was startled.

"Actually we don't know ... ."

"She heard us say it," I tried to explain. "You know what mimics kids are at that age."

"I hope it wasn't our house," Nuala Anne interjected.

"No, it was Mr. MacManus's home. You know, the T.D."

T.D. is a member of the Dail, the Irish parliament. God forbid that the Irish should call one of their parliamentarians an M.P.

"The next house down the road from us!" Nuala exclaimed, making an elaborately large sign of the cross.

"It was a big explosion ... fortunately no one was home ... . And your house was not damaged."

MacManus was off in Dublin at the Dáil session.

"Thanks be to God," Nuala said.

"Indeed, I'm sure you can go through to your house. However, there'll be a lot of us around for a day or two.

"Thanks be to God," I agreed.

"Fiona," the Garda said, "back into the van."

Reluctantly the wolfhound obeyed.

"Aren't you Nuala Anne?" The constable glanced at my wife's license before returning it.

"'Tis me name," she said, bowing her head modestly.

"Aren't we all terrible proud of you here at home, Ms. McGrail? Not all our exported celebrities have your dignity and grace."

Me wife turned deep red.

"Thank you," she said quietly.

"Haven't I been telling her that all along?" I said as I closed the rear door on our faithless hound and retook my seat.

"Enjoy your time at home." The young woman saluted.

"Isn't she sweet, the poor dear thing?"

"Nice ass too," I added, just to make trouble.

"Dermot Michael Coyne! What a terrible thing to say!"

"Just an observation," I said. "Teats are cute too!"

"You're obsessed with sex," she said, trying to sound as though she disapproved.

"Not as cute as yours!"

"Will you be quiet now, and the small ones in the car with us!"

"I will ... ."

"The woman is not from Galway," Nuala Anne observed.

"Ah?"

"She doesn't speak Irish like we do, not quite. There may be a touch of Kerry in her ... ."

"God forbid ..."

"Dermot Michael, give over! Isn't it important to you Yanks to know whether someone is from Texas?"

"If he is, he's probably carrying some kind of concealed weapon."

"Maybe East Mayo ..." Nuala continued, ignoring me.

Our daughter was babbling again in Irish at her little brother, who continued to gurgle and smile.

The breeding of Fiona and Sir Roy, an attempt to combine presumably long-lived genes of the species, was the alleged reason for our trip to Ireland--that and the opportunity to see our new Irish bungalow and to expose Nelliecoyne to Irish culture. The real reason was to restore my fragile Irish lass to her Connemara milieu and to the common sense of her mother, Annie McGrail. ("The poor dear child has to learn to cope with all her talents, Dermot Michael. Don't worry about it; she will in time." But I was worried about it.) We were to have supper with Annie and her husband, Gerroid, that night at Ashford Castle.

We passed a blackened hole in the ground, which had been Colm MacManus's house. Guards swarmed around it. Two of their vans were already parked next to the rubble. They had come up quickly from their barracks at Clifden. One of them waved us through.

"The lads set off a bomb," Nelliecoyne repeated.

Nuala sighed loudly.

"Whatever are we to do with that one, Dermot Michael Coyne?"

I was saved from the need to respond by Nelliecoyne herself.

"Ma, sometimes this little brat drives me out of me friggin' mind. He's so dumb!"

"Shush, darlin', he's only a little boy and you're a big girl. You should be nice to him."

"Yes, Ma."

Two vans with satellite dishes rushed by us as we turned into our driveway.

"It's them friggin' media vultures," my wife protested. "They'll find out I'm here, Dermot. I don't want to talk to them!"

"I'll keep them at bay," I said bravely.

"They'll want to know why I'm not singing. 'Tis none of their business! The friggin' gobshites!"

"'Tis not."

Why should anyone be interested in the fact that a young woman who had just earned a platinum disk for Nuala Anne Sings American announces that she's finished with her vocal career at twenty-five?

Why, indeed?

No reason given other than she was tired of singing--and on the flat of her back trying to save a baby.

"You can tell them I've taken up painting!"

"I can indeed."

We stopped in the bungalow's carport and stared down the road at the ugly black scar on the turf, a blot on the postcard-perfect azure sky, sapphire sea, and green vegetation. All right, our house had not been hit by the explosion. What if, however, we had happened to be driving by, or if Nellie--violating all our rules, had been too close to the house next door. I shuddered at the image of her thin little body limp and lifeless on the road. Nuala Anne was probably seeing a similar image. She snatched her son out of the car seat and carried him protectively to the door of the house.

"And tell them I won't have any exhibitions for twenty-five years!"

"Woman, I will."

Copyright © 2001 by Andrew M. Greeley, Ltd.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...