- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

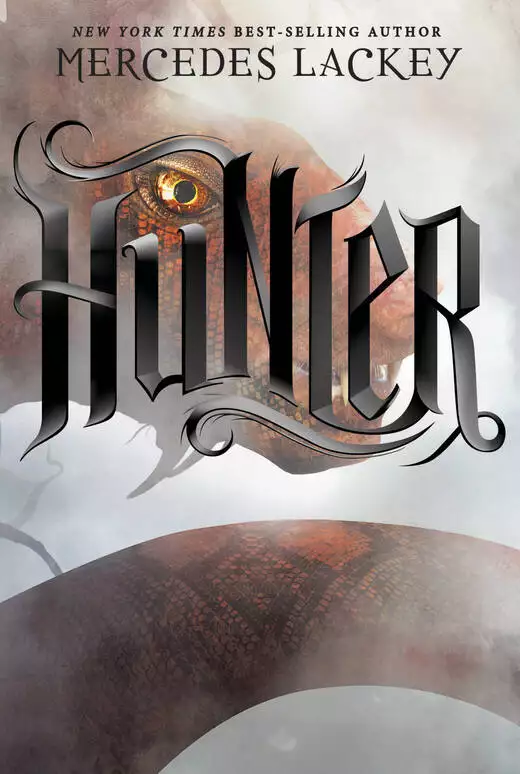

Synopsis

They came after the Diseray. Some were terrors ripped from our collective imaginations, remnants of every mythology across the world. And some were like nothing anyone had ever dreamed up, even in their worst nightmares.

Monsters.

Long ago, the barriers between our world and the Otherworld were ripped open, and it’s taken centuries to bring back civilization in the wake. Now, the luckiest Cits live in enclosed communities, behind walls that keep them safe from the hideous monsters fighting to break through. Others are not so lucky.

To Joyeaux Charmand, who has been a Hunter in her tight-knit mountain community since she was a child, every Cit without magic deserves her protection from dangerous Othersiders. Then she is called to Apex City, where the best Hunters are kept to protect the most important people.

Joy soon realizes that the city’s powerful leaders care more about luring Cits into a false sense of security than protecting them. More and more monsters are getting through the barriers, and the close calls are becoming too frequent to ignore. Yet the Cits have no sense of how much danger they’re in—to them, Joy and her corps of fellow Hunters are just action stars they watch on TV.

When an act of sabotage against Joy takes an unbearable toll, Joy uncovers a terrifying conspiracy. There is something much worse than the usual monsters infiltrating Apex. And it may be too late to stop them.

Release date: August 9, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hunter

Mercedes Lackey

anyway. I looked around at the rest of the passengers in the car—I’d noticed when I got to my seat that I was the only one there who was under thirty years old. I’d seen flashes

of fancy railcars like this in vids, and while waiting for track clearance at the Springs station, when I’d been down there with my Master. Stepping into the sleek silver tube with its rows

of heavily padded blue-gray seats had felt unreal. As I covertly examined the people around me, in their clothing that was obviously not handmade, I wondered if they were trying to figure out why I

had invaded their expensive, important world. They’d been studiously leaving me alone in that way that said they were curious but didn’t intend to actually say anything, while I stared

at the reflections in the dark windows and wished I were back in my little room. Or maybe they already knew what I was. Master Kedo had told me on the drive down to the Springs station that all the

personnel on the train were told about me, so maybe the passengers were too.

Now I was the only one still awake. Pretty much everyone else had their seats in the recline position, their cocoons on, and their privacy hoods over their heads and shoulders. It looked like a

scene out of one of the drama-vids we watched now and again, the ones that turned up in the weekly mail. I didn’t care for them much, but my best friend, Kei, loved them, so I always sat

through them without a complaint. That’s what friends do, right?

Well, okay, maybe some of them were watching their own selection of vids in there, but you couldn’t tell; they’d have their buds in and their glasses on. There was just row after row

of reclined seats, skewed so no one quite had his head in someone else’s lap, each person bundled up tightly like a swaddled baby, with soft black mounds over the top halves. The

cocoons were made of some fabric I’d never seen before, soft and plush, like kitten fur. I’d watched as they settled in for the night, and a lot of them had asked for Nightcaps. If

something bad happened now, they would all die without ever knowing they’d been in danger.

All but me. My seat was reclined, of course. I didn’t have any choice in that; all the seats had reclined and swiveled for night at the same time. The conductor did that for the whole car.

But I hadn’t fastened down the cocoon, and I wasn’t going to use a hood. I certainly wasn’t going to have a Nightcap. My Masters would have a litter of cats if I even looked at a

Nightcap.

Well, no, they actually wouldn’t; my Masters didn’t do that sort of thing. But they’d give me that look that said You know better than that, which actually made

you feel a lot worse than if they’d had a litter of cats.

I wanted to look out, even though I knew the view would be no different from daytime. The track was safe enough—well, as safe as things ever got out here below the snow line. It was

enclosed in a wire cage that was kept electrified for five miles in front of and behind the speeding train. Back when things were finally being put together again, after the Diseray, that was one

of the first things the army had figured out: the way to keep the trains safe. Outside the cage, though, that was different. Some places were safe, protected. Some…not. Some were hell on

earth.

I’d seen that hell on earth once, a small version of what could happen when the Othersiders decided there was a choice plum to pick and they were going to pick it. Two years ago; I was

fourteen then. Summer, of course; in winter, all the settlements are relatively safe, protected by snow and cold. Anston’s Well was—still is—a nice place, with nice people

in it. About thirty families, big enough to have their own storehouse and trading post. The Othersiders must have decided it had reached a point where it was big enough to bother with.

The first I’d known about it was when I got woken up from a sound sleep by the Monastery alarms. My Master Kedo was pounding on my door as I was stamping my boots on. “Summon!”

he’d said, so I’d summoned my Hounds, who’d joined his four that were milling about in the hall outside my room, and we’d met the rest outside in the snow. Everybody, and I

mean everybody, had piled out of the Monastery. Even the oldest and youngest; and the ones with no magic and no Hounds were armed.

When we’d gotten down to Anston’s Well, about a third of the houses were on fire, and there were monsters in the streets, trying to pull down people who were holding them off. There

were more monsters just outside of the palisade around the town; that was where Kedo had sent me. The Hounds and I…it was just a blur for most of the night. I did a lot of shooting—some

magic, but mostly shooting—while the Hounds kept what I was shooting at too busy to come at me. Kedo had given me an AK-47 with incendiary rounds, which the Othersiders I was up against did

not much like. The turning point had come when the rest of the Hunters from the other settlements finally reached us. By dawn, we’d driven the Othersiders off. The bodies that didn’t

dissolve, I think they carried off with them. We lost that third of the houses that were on fire, but we were so lucky…just two deaths, though nearly everyone who wasn’t a Hunter was hurt

or burned. But like Per Anston had said, “We can rebuild. We can’t resurrect.”

I wouldn’t show how scared I was now, like I hadn’t then; I’d spent a lot of time learning how not to show it, but I was scared. Of course, I wasn’t from a place that was

precisely safe, but it was safer than most of the territory we were speeding through. And I was going to be going out there into the worst parts of it, if not now, then soon. It would surely

be no more than a year before I was patrolling it.

I’m a Hunter, and that’s my job. There is no more important job in the world. Hunters stand between the monsters of the Breakthrough and ordinary people. If it hadn’t sunk in

before, that sure had been made clear to me the night Anston’s Well was attacked. I knew those people; they were my neighbors, and a couple of the hurt folks were my friends. They’d

come up to dance at the Safehaven flings, and I’d run off the Othersiders from their fields, and…that was when I knew for certain-sure that there was nothing more important than being a

Hunter. Because being a Hunter meant I could do something about the Othersiders that no one who wasn’t a Hunter could do. It had been the Hunters, not bullets, not RPGs, who had turned

the tide that night, who had kept Anston’s Well from being another one of those casualties in the war between the Othersiders and humans. This isn’t a job you pick, it’s a job

that picks you—but if I’d been given the choice, I’d still be a Hunter. That morning—on the way back up to the Monastery in the back of the truck, my Master Kedo had

given me this long and searching look. The measuring kind. I guess he must have seen what he wanted to see, because he’d ruffled up my hair and said, “Now you are a real Hunter,

chica,” and leaned back and closed his eyes, looking satisfied.

One of the stewards was making his way through the rows, checking on everyone. He had on the dark green uniform of the Train Service, which looks military, but isn’t, and had a serious,

square face with ginger hair. I wasn’t sure why he needed to check on people, but this was an expensive and very exclusive way to travel, so I supposed the illusion of always being served

came with it. No one flies but the military, of course; the skies are just too dangerous. There are other trains, not like this one, where people are packed in like cattle; they have to hump their

own luggage, bring their own meals. I saw them at the station, and it looked like the old pictures of people fleeing from a war.

Not me. I was told that once I was away from my Masters and home, I would always get the star treatment, partly because of what I am, partly because of my uncle. That was another thing that felt

surreal. It was hard to think I’m related to someone important. It certainly didn’t make any difference up on the Mountain.

The steward paused at my row, and I tensed a little, expecting a rebuke, or a demand to lie down and sleep, like everyone else. But instead, he leaned over the man between me and the aisle, and

whispered, “Are you really the Hunter?”

I nodded. His eyes went wide. “You’re so young!” he blurted. “You’re just a girl!”

I thought about telling him that I had been a Hunter since I was nine; then I thought better of it, since that didn’t fit with the story I was supposed to tell, and I should start using

that story right now. The Masters and the Monastery aren’t even supposed to exist, and when someone turned Hunter they were supposed to go to Apex City immediately, anyway. There aren’t

a lot of Hunters, after all. Maybe one person in a hundred or two hundred is born with the ability to do magic, and maybe only half of them become Hunters. There’s not another place like the

Monastery on the whole continent, at least not that I know of. Back at the beginning of the Diseray and the Breakthrough, Hunters tried to train themselves, and about half of them died before they

mastered their magic and learned how to work with their Hounds. So having Hunters report to Apex for proper training was the law; it was probably a smart law, too.

I just shrugged at him.

“Can I see the Hounds?” the steward breathed.

That took me by surprise. “Here?” I asked. “Now? I mean, sure, but…would that be…polite?” The Hounds are not exactly quiet about making their entrance, and I

wasn’t sure if even earbuds and cocoons would insulate these other important personages. Nor how they would feel about being awakened by a full pack.

Now, the Hounds would probably love it. Sometimes I think that they feed off of admiration as much as they feed off of manna. Although, maybe admiration is another sort of manna.

He glanced at the rest of the passengers, but when he looked back at me, his face was all lit up with excitement, and I couldn’t help smiling at him a little. Sure, for me, I summon the

Hounds, and it’s just Tuesday, but even for the folks in the settlements on the Mountain, seeing the Hounds is a special thing, so how much more special would it be for someone who spent most

of his life taking care of rich people in a train?

“The rec car is empty,” he said eagerly. I nodded, shucked myself out of my cocoon, and edged into the aisle. I followed him through two more cars full of silent cocoons and into the

rec car. We picked up two more stewards on the way. One of them stopped and whispered something into a grate at the end of the car; I guessed that was probably the car-to-car comm, or something

like it.

He was right, the car we ended up in was empty. The autobar blinked its lights at us, then went back to wait mode when we didn’t go get ourselves drinks. The game consoles were silent, as

were the gambling tables.

There was some clear space at the back with fold-down exercise machines. That was where I went. By now I had quite an audience, and more were coming; that steward who had whispered into the

radio must have spread word about what I was going to do through the rest of the train. It made me a little nervous because I didn’t usually do this with an audience; normally the Hounds are

already with me when people see them. I closed my eyes and envisioned the Mandala; that opened my mind to the Otherworld.

The Mandala, of course, is my Mandala, the same thing that’s branded on the backs of my hands. They’re tattooed, but the tattoos trace over the actual Mandala. Every

Hunter’s Mandala is a circular diagram, and every one is different. They’re really pretty, actually; if you didn’t know better, you’d think they were just fancy decoration,

like regular tattoos. There’s an outer circle, then a circle of little signs inside that, one sign for each one of your Hounds, then another circle, then maybe a triangle or a square or a

hexagon. There might be signs inside that, but there are always two squares on top of each other after that, making an eight-pointed star. Then in the center of that is a sign that’s you. If

you know how to read them, they’ll tell you how many Hounds the Hunter has, but there are other things in the Mandala that no one knows how to read. They look sort of like the Mandalas in

some of the Buddhist or Hindu god-paintings at the Monastery, but the language isn’t Chinese or Sanskrit. They get burned into your hands when your magic wakes up, the first time something

really bad happens to you that involves Othersiders. If you’re born a Hunter—because you can’t be made a Hunter—the Hounds will come to you then, for the very first

time, and the act of them coming over from the Otherside burns the Mandalas into the backs of your hands.

With my eyes still closed, I drew the three Summons Glyphs in the air with sweeping gestures; if I opened them, I knew I would see the Glyphs hanging in midair, drawn in flames, which was

something of my signature. Every Hunter uses the same three Summons Glyphs. They look like runes; maybe they actually are runes, but if so, no one has ever translated them. They tell the Hounds

that the Hunter is calling them. My Glyphs, being drawn in fire and all, are very showy, which is odd, considering I tend to keep myself to myself and drawing attention makes me feel naked. I heard

the group’s swift intake of collective breath.

With an abrupt gesture, I cast the Glyphs to the ground, where they lay burning just on top of the carpet, and I opened the Way—and all I can tell you about that is how it feels. It feels

as if I am reaching across the Glyphs with my gut and opening a door. Weird, I know. But that’s how it feels. The Glyphs make the door, and at the same time, they put a kind of seal on it

that nothing can cross but the Hounds. Now I opened my eyes, in time to see them bursting out of midair between me and the onlookers.

You know, that never gets old, no matter how many times I do it. There’s this amazing feeling, a Wow, these are my Hounds, and I brought them! And, for me at least,

there’s also a feeling as if my best friends in the whole world had just come through the door into my room: an I’m so happy we’re together again! I always have that, even

if I’m summoning them right before a bad fight.

Someone gave out a nervous shriek; all seven of the Hounds turned their heads in his direction to stare with their flaming eyes. Little flickers of flame danced over their coal-black coats. Some

Hounds always look the same, but mine don’t. I was one of the three Hunters on the Mountain, including my Master Kedo, who had Hounds who could change what they look like. They’d chosen

to appear as black greyhounds this time, which was a good choice: there wasn’t much room in the rail car for anything bigger, they were intimidating without inciting panic, and there was no

way that their usual forms would have fit.

“They just look like dogs,” one of the stewards said doubtfully. My pack leader, Bya, looked over his shoulder at me and dog-grinned, then, before I could stop him, whipped his head

back around and blew a jet of flame at the doubter. There were shrieks, but I stepped in between them, right into the flame, and let it play over me.

“Illusion,” I explained, as the panic subsided. That wasn’t the truth of course; Bya had merely ordered the flames not to burn anything or anyone, but knowing that my Hounds

could turn the laws of physics inside out would only make these people’s poor brains explode. I know it made my brain explode the first few times I saw them do impossible things.

After that, the Hounds went into superstar mode and graciously accepted the admiration of the crowd. Everyone wanted to touch them, pet them, and the Hounds were in the mood to accept buckets of

that—probably since we hadn’t Hunted in two weeks, and they were bored and hadn’t gotten what they considered to be their just quota of adoration for a while. When they’re

in a petable form, they go all out; their coats are as sleek and soft as the antique silks I’ve handled at the Monastery.

In a situation like this one, I don’t have to dismiss them, they go off on their own. When they got tired of it all, they went to the Glyphs still burning on the floor and leapt through to

the Otherside. Bya was last. Bya seems to like people more than the rest of them. When he went through, the Glyphs vanished, and the crowd mingled around a little more, asking me stuff about them.

I felt pretty awkward, but at least they were asking me about the Hounds instead of myself, so I managed not to get too tongue-tangled. The radio at the end of the car chimed three times after a

bit, and they all kind of alerted on it and dispersed back to their duties. All but the steward of the car my seat was in. I guess he got to stay with me because I was in his charge.

“Would you like something to drink?” he asked, pausing at the autobar. “You might as well, the bar can mix you up just about anything.” He stood there with his hand just

over the keypad, waiting.

I thought for a moment. It was just a little intimidating, and a little intoxicating. Here I was, in a situation I had never found myself before, a situation where I could have absolutely

anything I wanted.

Almost anything, that is. That put things into perspective. I really wanted to turn the train around and go back home. For a moment, homesickness swallowed me up. But I kept my Hunt-face on,

just as I’d been taught.

“You choose. I just don’t know what the options are. Something soothing, sweet, and hot with nothing like a drug or alcohol in it,” I said, thinking I was going to get some

sweet, hot tea, which I much prefer to the hot buttered tea some of my Masters like. Well, it isn’t real tea—nobody on this continent can get that anymore—it’s herbal

tisane. But it’s real butter. Cows can’t live up in the mountains, but goats and sheep can, and we have both at the Monastery. Sometimes we get cow butter and milk from the settlements,

but mostly we rely on our own herd for that sort of thing.

“I know just the thing,” he said, and went to the autobar. He brought back something medium brown and opaque, with an intriguing smell. I sipped it; it was odd but good. Creamy

and sweet. “Hot Chocolike,” he said, and gestured for me to follow him. I did, sipping as we went.

At the vestibule to my car, he paused. “If—if something were to happen to the train—you and your Hounds would protect us, right? We’d be all right with you here, until

help came, right?”

I thought about that. Thought about the likelihood that if there was an attack that involved something big and nasty enough to break through the electrified cage, the train would probably crash,

and at the speed it was going, not even the crash-bubbles would save us. And that if any of us did survive, we’d be too injured to do anything, or unconscious. We’d be too far away from

Apex for an Elite team to get here in time. I thought about other possibilities that didn’t involve crashing, in which case the armed cars at the front and the rear of the train would do a

lot more about protecting us than me or the Hounds ever could. I mean, there were machine guns with armor-piercing, blessed bullets in there, or incendiaries and mortars, and some trains were even

rumored to carry small missile launchers with Hellfires loaded. I’m cursed with a very good imagination, and right then, what I could imagine was terrifying.

But my Masters had told me that when I got out here in the world, the people here would look at me differently from how they did at home. That Hunters were some sort of legendary beings off the

Mountain. Not that Hunters weren’t respected on the Mountain, because we were; everyone knows the job we do is dangerous, and we get the respect a warrior merits. But nobody treats us like

we’re minor gods or something.

We didn’t get a lot of live vid on the Mountain; we were off the grid, and our electricity had to be saved for things that mattered, so mostly it was just the officially mandated stuff we

warmed up the vid-screen in the community hall for, or old, stored stuff on drives and disks that you can watch on a solar-powered tablet, or things that came in the weekly mail. We don’t

lack for electricity, because we can keep the lights and the comm system and the intranet going all the time, but we’re all taught to be mindful, very mindful, of waste. That kind of

mindset goes all the way back to the Diseray, when no one had much of anything, and everything was being scrounged. Think twice, act once, is what everyone says. When kids are taught to read

and write, it’s one of the first things they print out.

That was when it hit me: off the Mountain, Cits—that’s ordinary people who live in the cities—absolutely believed what the vids showed them. And the vids showed them that

Hunters were able to protect them from anything. Then it hit me that there must be a reason for that.

I wasn’t going to do him any good by breaking that illusion now, was I? I had to think about this before I answered him. Think twice, act once.

“Yes,” I said simply. “So long as you forget how young I look and do exactly what I tell you to.”

Enough of the Hunter mystique must have attached itself to me when I summoned the Hounds that he just got this hugely relieved look on his face and sighed. Then he opened the door for me and

waved me through.

I went back to my seat and perched on it, legs crossed in lotus position, zazen style, sipping the drink. It must have been terrible territory we were passing through, for him to have asked that

question. Now I really wanted to see what was out there, even though I had goose bumps all up and down my spine. It’s what’s unknown and unseen that scares me the most. That had

almost been the worst of it, that night at Anston’s Well. I mostly couldn’t see what was coming at me. Flashes. Teeth, eyes, claws. I knew some of the monsters of the

Othersiders, but by no means all of them—some we still don’t have names for, some came out of other mythologies, ones we don’t have books for. Nothing is scarier than what you

don’t know.

There was a lot of speculation among the folks that depended on the Monastery about just what happened to cause the Diseray—that’s what everyone calls it, the time when the old world

that created vids and trains and planes and all of that got turned upside down. It’s been about two centuries and a half, a little more maybe, since it happened.

I looked over at the steward, who was doing something on the keypad. The lights got even dimmer. I was just a ghost of a reflection on the opaqued window.

I wondered if people like the steward ever thought about it. I do. The other Hunters tied to the Monastery don’t so much, but I do.

I knew there were volcanoes and earthquakes, because the Island of California used to be part of the continent, and there’s Old Yeller, a volcano where a park used to be that still sends

up ash plumes that ground the Air Corps, and Olympus, another one in the northwest that took out a whole city. Every so often, when the wind blows from the right direction, we still get ash-plumes

that mean everyone has to wear masks until they settle, and the ash in the the sky is the reason why there’s snow on the mountains all year long.

I stared at my reflection in the window, with my dark brown hair making a kind of shadow around my face, glad I hadn’t lived through those times. Bad as right now was, I could imagine how

much worse it had been.

The steward came back over when he saw me looking at him. “Anything I can do for you, Hunter?” he asked. “Anything you’d like to know about Apex, for instance?”

I thought, well why not? It would be a good idea to find out some of what I should play dumb about. “What do they tell you Cits about the Diseray?” I asked. “I never learned

all that much about it. And please sit down; it gives me a crick in my neck to look up at you.” He gave me a funny look, but since I was curled up, he sat gingerly down on the edge of my

seat, as far away from me as he could, to be respectful, I think.

“We don’t dwell on it.” He shrugged. “Mostly they give us a couple days on it in school, so we know to be properly grateful for being safe now. There were plagues, which

we cured. Storms got worse, which we couldn’t do anything about, and which is why only the Air Corps flies now and we rely on trains. The South and North Poles switched, which we can’t

exactly do anything about either. There was a nuke set off on purpose by Christers on the other side of the world. And the Breakthrough, when all the magic and monsters happened. That’s

mostly what I remember from school.”

I nodded. I’d read the diaries of some of the people who gathered for safety at the Monastery; farmers, hunters—the ones who hunted for food, not my kind—craftsmen, a couple of

soldiers—it had been a real mixed bunch. That was when they all pitched together and built Safehaven, the first settlement, the one right at the foot of the Monastery, up in the snow

year-round. The Monastery itself predated the Diseray; it was started by Tibetan Buddhists, but by the time things got sorted out, it had turned into a home for every kind of religious folk but

Christers. Right now there were some Celtic, Norse, Greco-Roman, and shamanistic traditionalist types, several Native Americans, including my Master Kedo, some Shaolin monks, a couple of Hindus,

one lone Sikh, and a couple of Shinto Masters. The one thing they’d all had in common was that there was some magic tradition in their religions, which helped them understand the Othersiders

and how to fight them, and that they were all determined to work together to help each other and people who came there for safety.

“Why?” he asked. “What do they tell you?”

I told him part of the truth. “Mostly we read the stuff that the people who settled our parts left behind. Out where I’m from, those are kind of like manuals for what not to do. They

don’t go into the stuff that happened outside our mountains, or the why, or the parts about what other people did at Apex so much as the what we did, if you get my

meaning.”

I couldn’t tell him the whole truth, of course, that the Monastery had probably the best records around of that time. The Monastery was a real anomaly; I don’t think there is

anything else like it, on this continent at least, but…there’s a lot of continent, and even now, hundreds of years later, there are still holdouts and warlords and places where people

hunkered down and survived that no one has run into yet.

“Well,” he said, “the big thing that saved people around Apex was the military. Over on the East Coast, where Apex is now, there were a lot of military installations; they were

the backbone of defense, and the place people went to looking for safety. When the first Hunters emerged, they naturally went there too. That’s how Apex started; a lot of really smart tech

and builder people, and the military, and the emergent Hunters, protecting everyone that came to them.”

He didn’t say anything about the Christers, other than what everybody knows, that some fanatics set off a nuke, but there didn’t seem to be a lot of Christers in Apex from what

I’d seen. The Christers of that time thought it was their Apocalypse, and the Masters say they were all confidently expecting to be carried up to Heaven while everyone that wasn’t them

died horribly, or suffered for hundreds of years. Only that didn’t happen, even when some of them decided that the Apocalypse must need a kick-start like a balky engine, and set off some sort

of nuke in what used to be Israel. They still didn’t get carried up to Heaven, not one; they just died like everyone else, so that’s why it’s called the Diseray instead of the

Apocalypse.

“So what do they say did it?” I asked. “The Diseray, I mean? And the Breakthrough.”

“Probably the polar switch, maybe the nuke. Maybe both.” He shook his head. “Maybe something we don’t even know about.”

That wasn’t the way I’d been taught it happened. The Masters say that it didn’t all happen at once, that things just got worse and worse until the bombs went off. And that,

they think, is what caused the Breakthrough.

But even the Masters don’t know that for certain-sure. The only thing they know for fact is that in the middle of disaster after disaster, the Othersiders came through, and with them came

magic.

I sipped my drink. “Sometimes I think it was like the old story in one of the books I read when I was little, where this girl named Pandora opened a box and everything horrible burst out

of it and spread over the world.”

He smiled at me. “So that would make the Hounds as Hope in the bottom of the box? That sounds about right.” I smiled back, oddly glad that he knew the story too. Most of the

Othersiders are monsters: Drakkens, Kraken, Leviathans, Gogs and Magogs, Furies, Harpies, things we d

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...