- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

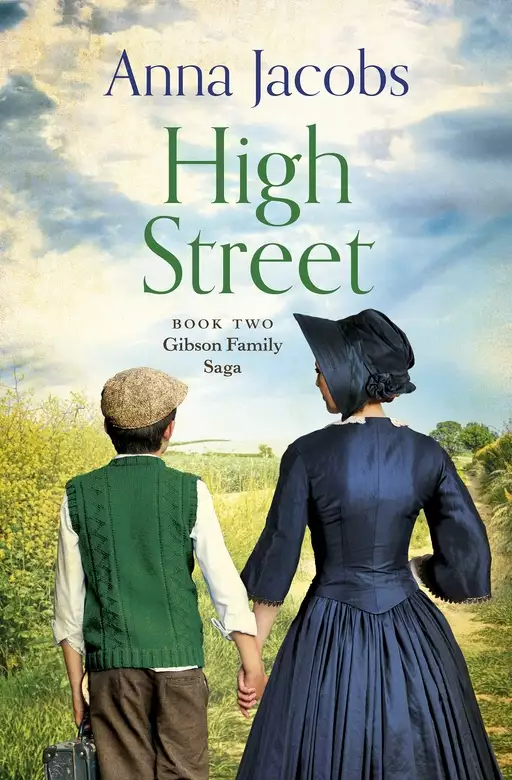

The second in the heartwarming Lancashire saga series that began with SALEM STREET, by beloved author Anna Jacobs.

In 1845 Annie Gibson can finally leave Salem Street. Her dreams of being able to open an elegant dressmaking salon in the High Street of Bilsden, a Lancashire mill town, have come true. And she is going to take her father and his second family with her, away from poverty, away from the Rows.

But Annie has not left trouble behind. Someone is trying to undermine her business. Her family have their own ideas about what they want to do with their lives. And several men are persistently trying to win favour with the beautiful young widow - including Frederick Hallam, the mill owner, and Daniel O'Connor, her childhood friend.

As Annie gets better acquainted with both, she becomes increasingly confused about her feelings. Can she really be in love And can she risk trusting any man again.

(P) 2021 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Release date: June 7, 1995

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 441

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

High Street

Anna Jacobs

“They’re all coming to live with us when we move, and that’s flat!” declared Annie, her pale complexion slightly flushed and her eyes glinting green in the candlelight.

Tom jabbed the poker at the fire and then thumped another piece of coal into the red heart of the flames. Spring it might be, but the evenings were still chilly. “You’ve run mad, our Annie, mad! It’s Dad’s job to provide for his second family, not ours. We’ve enough on our plates with the business. We’ll never make a success of it all if we have that lot hangin’ round our necks, eatin’ us out of house and home!”

Getting on in the world was one of the few things about which the two of them were usually in agreement.

“They’re our brothers and sisters, Tom.” Annie’s voice was clear and pleasant, her accent no longer that of the Rows. She had escaped from Salem Street when she was twelve to go into service with the local doctor and his wife, and had only returned when she was seventeen because a rape had left her pregnant.

Rejected by her sweetheart, Matt Peters, for the same reason, Annie had later shocked everyone by marrying Charlie Ashworth, commonly known as Barmy Charlie. He was older than her own father, as well as slow of speech and thought after an accident in the mill. But Charlie was not too slow to make a good living from second-hand junk, and not too stupid to save the money he earned. Unable to father a child of his own, he had welcomed Annie’s bastard son, William.

Annie had grown quite fond of her husband, in a motherly way. She had looked after his physical needs, invested his hoard of money and helped him to expand his junk-collecting business. At the same time, she had built up a thriving business of her own, refashioning second-hand clothes or making cheap new ones to sell at the weekly market. And as the years passed, she had continued to save their money and to invest it wisely.

When Charlie had died the previous year, Annie had brought her brother Tom into the junk trade as a full-time partner. With two sharp-witted people at the helm, the business had gone from strength to strength.

But it was not the business that concerned them now. “They’re our brothers and sisters,” she repeated. “We can’t let them want.”

“They’re only half-brothers and sisters! An’ they’re dear Emily’s brats, too, which puts me right off them.”

Annie spoke quietly, but there was steel underneath the soft tones. “Emily’s dead, Tom, and two of her children with her. Now, Dad needs our help. He can’t manage on his own, with four children to look after.”

“Let Rebecca help him, then. She’s the same age as you were when our mam died. You managed.”

“Rebecca couldn’t cope. Mam had taught me how to do things. Emily couldn’t look after the house herself, let alone teach Rebecca how to do it. Those children are as ignorant as the toss-pots in Claters End.”

“All the more reason for not takin’ them to live with us.” His voice became coaxing. “Look, Annie, we can slip them the odd shilling or two to help out. We can see that they don’t want.”

“No. They’re coming to live with us.”

Tom slapped his hand on the table, and the thump made his nephew William, sitting quietly in the back room, glance apprehensively at Kathy, who lived with them and helped with the sewing and the housework. Kathy shook her head. Best to stay out of it when Annie and Tom were quarrelling. They might not look alike, for Annie had inherited their mother’s red hair while Tom had their father’s tight brown curls, but they were alike in so many ways that clashes were inevitable.

“Besides,” Tom went on scornfully, “Dad’ll soon find another woman to look after him. It didn’t take him long after our mam died, and it’ll take him even less time to forget Emily!”

“I don’t intend to give him the chance to find another woman this time. If he lives with us, he won’t need anyone else.”

Tom gave a snort of laughter. “You should know him better than that. He can’t do without it! He’ll soon find someone to comfort him, trust old randy-pants for that!” Not that he blamed his father, really. A man’s body had its needs, and Tom only hoped he could enjoy that sort of thing for as many years as John Gibson obviously had, judging by the number of children he had fathered. Mind, the same urge could drive a man to do foolish things, like his father marrying that silly bitch, Emily. Tom was not going to be caught like that. He looked at Annie speculatively and tried another tack. “It’d not be fair on your William to have the other kids living with us.”

Annie snorted and shook her head. “I think it’d be good for William. And you needn’t try to get at me that way, Tom Gibson, because it won’t work. You’re the one who showed me that I was spoiling him, and taught him to stand up for himself. You were right then, but you’re not right now. William will love having company. He already follows our Mark around like a lost puppy dog whenever he can.” Her lips thinned, “And as I’ve no intention of ever marrying again, I shan’t be giving William any brothers or sisters, shall I?”

They were silent for a moment, both busy with their own thoughts. Tom was glad on the whole that Annie had kept all men at a distance since Charlie died. It meant she was less likely to marry and bring someone else into the business. Sometimes, however, as a man, he could not help thinking that it was a waste for a woman as lovely as his sister to stay so determinedly single.

Annie’s thoughts were still on her plans. She went over and linked her arm in his, her voice becoming coaxing. “What’s come over you, Tom Gibson? You were quite pleased about my idea last night. If Dad had been at home, we’d have told him then. What’s made you change your mind today?”

Tom put his hands on her shoulders and held her at arm’s length. Blue eyes stared into green, and neither would give way. He was not much taller than she was, but powerfully built, with a hard, muscular body. From his crinkly brown hair to his squarely planted feet, he seemed to exude strength and vitality. Lucy Gibson’s children were of a different breed to those of poor Emily.

“Look, Annie, I’ve had time to think about it since then. It makes no sense to lumber ourselves with Dad and four young children, just when we’ll need all our wits and every penny we can scrape together to expand the business.”

“Sally left me all her money—”

“Ill-gotten gains!” he mocked, for their neighbour Sally had started life as a whore and ended it as a kept woman, and he knew how much Annie valued respectability.

She flushed at his words. “I don’t care. She may not have been respectable, but she was a good friend to me after Mam died. And she left me a tidy sum, as well as the two cottages. Poor Sally!”

Tom opened his mouth to continue the argument, but Annie gave him no chance to speak. “Anyway, I explained it all to you last night. Dad’ll go on working at Hallam’s Mill. He’ll bring in enough money to clothe and feed them all. And Mark’s a clever lad. He’s twelve now, old enough to be a real help to you in the business. I know Luke’s a bit slow, but he’ll improve, now that he hasn’t got Emily nagging at him all the time. How she could treat her own son like that, I’ll never understand! It’s no wonder poor Luke’s so nervous. She never stopped picking on him. And Rebecca’s nearly ten. She’ll be a big help in the new house, and she can learn to sew and help me in the salon as well.”

“Aye, you said all that last night. An’ Joan’s five, a snotty-nosed, whining brat who looks just like her sister, May.”

They were silent again, as they both thought of their stepsister May, child of Emily’s first marriage, who had left home a few years ago and was now living with their full sister Lizzie somewhere in Manchester. An unsavoury pair of girls, they were. Tom hoped he would never set eyes on them again. They made his flesh creep. Unnatural, they were. Man-haters, the pair of them.

“Aye, it’ll be a pleasure to have little Joan snivelling round the house, won’t it?” he jeered, pressing his advantage.

The old Annie would have lost her temper and flung something at him. The new one, seasoned by death and illness, shook her head and said very quietly, with tears in her eyes, “I’m set on it, Tom. I won’t see them want while we can help. Either you accept that – and them – or you go your own way.” Her expression was too old for someone who was only twenty-five.

Tom’s eyes were the first to drop. Funny, he found himself thinking, not anxious to capitulate but seeing no way round it, funny how lovely a woman Annie was when she’d been such a scrawny stick of a child. How he used to tease her about her red hair – a rich auburn now – and her green cat’s eyes! Those eyes were large and luminous, in a finely drawn face. If she’d encouraged them, the fellows would have been queuing up to court her, regardless of whether she had money or not. But she didn’t encourage any familiarities. After the rape, she had been glad to marry an old man like Charlie Ashworth, glad that he could give her no more than his name. Tom stared at her for a minute longer, but she gave no sign of yielding. “Damn you, our Annie!” he said feelingly.

“What does that mean?” Her voice was cold.

“It means you’ve got your own way, like you always do, but damn you, Annie, for makin’ me do it! An’ it’d just better work out all right, that’s all!” He turned and flung the front door open. “I need a drink. You can go an’ tell him yourself.” He slammed out of the house before she could answer, out to Claters End and his friend, his very good friend, Rosie.

A few days later, Annie walked briskly along Bilsden High Street, enjoying the early morning sunshine. Her full black skirts swished about her ankles and the black ribbons on her bonnet fluttered cheerfully in the breeze. So eager was she to get to her destination that she did not notice the gentleman sitting waiting in his carriage who raised his hat politely to her.

“By Jove!” he murmured to himself. “Annie Ashworth’s turning into a real stunner!” Frederick Hallam, largest mill owner in the town, was a noted connoisseur of female beauty. “Quite the lady of fashion too,” he added thoughtfully. “Well, well! Who’d ever have thought someone from Salem Street would turn out like that?” His eyes lingered on the slim figure until it turned the corner.

Annie would not have classed herself as a lady, or even aspired to be one. She was a businesswoman and proud of it. Today, however, business was forgotten and she could not hide the excitement that was bubbling up inside her. Frederick Hallam was not the only man to turn and stare at her. Her eyes were sparkling and her lips were half-parted in a smile of anticipation. Even the weather seemed to reflect her joyful mood and was making a glorious halo of the auburn curls that had escaped from under the bonnet brim, for the sun was shining brightly after yesterday’s showers, giving a promise of warmth to come after the long hard winter that had tried them all sorely and taken the lives of so many of the weaker inhabitants of Bilsden.

Annie turned right into Market Street, followed the road as it curved upwards away from the town centre, then turned left into North Road. And there at the first corner she turned left again and stopped for a moment to draw a deep breath of satisfaction and survey her future home, Netherleigh Cottage. No terraced rows of narrow houses here in Moor Close, but neat detached villas with carefully tended patches of garden, and one or two slightly larger houses with iron railings – how different it all was from Salem Street! And how beautiful the trees were, with their froth of young leaves! There were no trees in Salem Street, only a sour patch of earth under the high wall of Hallam’s Mill that cut off the light and cast permanent shadows on the little terrace of eight houses.

At Netherleigh Cottage Annie stopped again and sighed happily, running her fingertips along the top of the low stone wall. She owned this house and was here to receive the keys from her former tenant, Michael Benworth, overseer at Hallam’s Mill. As soon as she could, tomorrow if possible, she would be moving in. After a while, she realised that she had been standing by the gate for several minutes, lost in thought, and glanced round guiltily to see if anyone had noticed. But the street was quiet and the only people in sight were those walking past the end of the little cul-de-sac.

“Netherleigh Cottage.” Annie murmured the name aloud as she pushed open the gate. The house was an anachronism so near the busy centre of a Lancashire mill town, for it had been a farmhouse in its day. Even its name was a misnomer, for it was much larger than a cottage. It had somehow managed to escape demolition when the farm land was sold to a cotton spinner, and had even retained half an acre of land hidden at the rear behind a high stone wall. It stood part way up the lower slope of Ridge Hill, just above Hallam Park and a little higher than the town centre. She looked upwards at the crest of the hill behind it which you could see between the houses. Unlike her cottage, the houses up there on the Ridge were huge, commanding a sweeping view of the grey slate roofs of their poorer neighbours and of the brooding mills with their tall chimneys.

Frederick Hallam, just turning into his own drive on the Ridge, would not have thanked you for a rural vista. His father had built Ridge House to be a part of Bilsden, and like his father, Frederick enjoyed looking down on the town that his family had helped to create, relishing the unlovely signs of wealth in the making. “There’s progress for you!” he would declare. “Forty years back, when I was just a little lad, there were only a few cottages and some scrubby farms, and now look at it all! Those Rows are like a bloody great beehive, teeming with life. That’s real progress, that is!”

Frederick’s wife, recently dead in the influenza epidemic, had hated Bilsden, hated her husband too, for his blatant womanising and sarcastic tongue. And as the years passed, he had not troubled to hide his scorn for her timid ways, though she had never dared to show her resentment of that. Now, Frederick admitted, though only to himself, he was enjoying life without Christine’s drooping presence. How many times had that miserable face driven him out of the house to seek pleasanter companionship?

Near the park, its spire just showing from Moor Close, stood the grimy little parish church of St Mark’s. It had been lavishly endowed in a bygone age by the Darringtons who were still, technically speaking, lords of the manor of Bilsden. The present Lord Darrington, however, chose to live elsewhere and kept only a skeleton staff at the Hall to look after his elderly aunt who refused to be moved from her childhood home. It was rumoured that she abused her nephew roundly whenever she saw him for deserting his land and duties. Frederick Hallam had tried once or twice to buy the Hall, which was a great barn of a place with the best views on the whole Ridge, but even George Darrington balked at this. Jonas Pennybody, the family lawyer, had been instructed to inform Mr Hallam that it was useless to persist. One did not sell one’s birthright.

Annie had nothing to do with St Mark’s Church. She worshipped her Maker at the Todmorden Road Methodist Chapel on the other side of the town. The latter was an ugly red-brick box of a building only thirteen years old, standing at the western end of the Rows. In it, the largest group of Nonconformists in the town met to worship; there, too, they held their Sunday school and their evening classes in reading and writing. Annie herself had learned to read and write in that humble chapel, becoming one of the few girls to progress to the advanced class and be taught by the minister, Saul Hinchcliffe.

At the eastern end of the Rows stood the Catholic Church, a small shoddy place, also in grimy red brick. It had been built to encourage the Irish to settle in the town at a time when labour was scarce. To the parson of St Mark’s, it was living proof of the dangerous radicalism of the times that papists were allowed to build churches and conduct their Romish rites on English soil. And as for this shocking idea the Chartists had, of giving every man a vote, just let them try it! He and every right-thinking English gentleman knew where that sort of thing led. Look at France! What good had the Revolution done the common man there? None! They’d had to bring back a king again, hadn’t they? And things were still not settled there, either. Europe was in a mess, that was evident, and it was free-thinking which had wrought the havoc. Men of the poorer sort should know their place and stay in it.

Theophilus Kenderby did not hesitate to trumpet his views from the pulpit, but his words fell upon stony ground, and attendance at his services was perfunctory and mainly female. Most of the manufacturing classes of Bilsden were self-made men who had not been content with their station in life.

Frederick Hallam said outright that the old parson was still living in a bygone age and would not recognise progress if it hit him smack in the eye. Frederick only attended the church at Easter and Christmas for appearance’s sake, though his daughter was very devout and attended St Mark’s regularly. He considered church-going a waste of time, but it gave the womenfolk something to do, so he had subscribed to the odd charity in Christine’s name and allowed his coachman to drive her and Beatrice to and from the weekly meetings of the Ladies’ Society for the Relief of the Deserving Poor.

While Frederick Hallam was staring out over the town in which he owned at least a quarter of the property, Annie was walking along the path to the front door of Netherleigh Cottage. She noted with satisfaction that the garden was neat and tidy and that the windowpanes were twinkling in the sunlight. It was a pretty house, square and symmetrical, built of stone, with large dormer windows punctuating the grey expanse of slate roof. Benworth had been a good tenant. Even when his children had grown up and left home and his wife had died, he had stayed on with his one remaining unmarried daughter because of his love for the place. Annie thought this wastefully extravagant when he could have been putting his money to better use.

Well, she thought smugly as she knocked on the door, he’ll have to get out now that my years of frugality are starting to pay off. I had enough money saved to snap up Netherleigh Cottage before anyone else knew it was for sale. It stands to reason that half an acre of land so near the town centre will be worth a lot of money one day. And I have the two other cottages as well, thanks to Charlie’s savings. They’re smaller places and not nearly so well-situated, but they’re mine. There I go, forgetting again! I’ve got four cottages now, including the ones Sally left me.

The front door of the house opened and Michael Benworth came out to stand on the step as he greeted her. He was two years younger than her father, the same age as the century – forty-five – but he looked fifteen years younger than her father, she thought, returning his stare coolly. My dad’s worn-out, after all those years in the mill. And being married to Emily didn’t help much, either. She looked again at Benworth, whose hair was only lightly flecked with grey, and whose body was still lean and muscular. Before he knew that she owned the house, he had made an attempt to court Annie, but she didn’t need or want a husband; she could look after herself.

“Good morning, Mrs Ashworth. You’re very punctual. It’s a lovely day, isn’t it?”

“Good morning, Mr Benworth. Is the house ready for my inspection?” She couldn’t bear to waste any time on chit-chat now that she was here. She wanted the house to herself for an hour or two to gloat over. That was why she had told Tom not to join her till later in the morning.

Benworth’s gaze was admiring, but he followed her lead. “Yes, everything’s ready. My daughter’s just finishing the last bit of clearing up in the kitchen. Won’t you come in and look things over?”

Annie stepped over the threshold and paused for a moment to admire the square hallway. Fancy this much space, just for an entry! It was as big as most rooms in the Rows. Her eyes missed nothing and she was pleased to note how spotless it all was. You could feel a clean house, somehow.

Without waiting to be asked, she opened the door to the front room that her family must now learn to call the parlour. Houses in Salem Street had two rooms on the ground floor, front and back, and two tiny bedrooms upstairs. This house had several rooms on each floor. In this house, she would have her own bedroom and the parlour would be nicely furnished and kept for best. Her standards would come as a shock to her half-brothers and sisters after their mother’s slovenly ways, but they were young enough to adapt. It was only her father she was worried about – how would he fit in? She wasn’t going to let him start telling her what to do, father or not! She had been her own mistress for years and she liked it that way.

Annie followed Michael Benworth round the ground floor and then upstairs, still musing about the future. “Yes,” she said as they came back downstairs, “you’ve left everything nice, very nice indeed.”

“It’s Mary who must take the credit for that. She’s a good housewife. I don’t think you’ve ever met my eldest daughter, have you?” He opened the door at the back of the hallway and ushered Annie through to the kitchen. “Ah, there you are, my dear.”

Annie was expecting a girl, but it was a woman of about her own age who turned to greet them. Mary Benworth was tall, almost as tall as her father, towering over Annie, and she had his wavy brown hair and bright blue eyes. She didn’t seem in the least put out to be discovered with her sleeves rolled up, a dirty apron over her dress and her hands immersed in soapy water. Annie liked her better for that.

“How do you do, Mrs Ashworth. I’m afraid I can’t offer to shake hands with you, because mine are wet. I’ve nearly finished in here, and then that’ll be it.”

“I was just saying how nice everything looks.”

“I like to keep things clean.”

“I hope that you’ve found somewhere suitable to live.”

“We’ve found a house in Church Lane. It’s a nice little house, but Father will miss his garden.”

“I’m sorry about that. We know nothing about gardening. We shall have to learn.”

Benworth moved over to look out of the window. “It’s a good garden and always repays a bit of work. The soil’s rich and the fruit trees bear well.”

She could hear the love in his voice. “Fruit trees! I hadn’t realised…” She smiled apologetically. “I don’t know one plant from another. None of us do!”

“I’d be happy to help you and your brother until you know enough to look after the garden yourselves.”

Mary swung round. “Now, Father, let it go!”

“I couldn’t impose on you!” said Annie.

Benworth ignored his daughter’s frown and said eagerly, “It’d be no imposition. Our new house,” he grimaced and looked longingly out of the window again, “has no garden at all and I shall not know what to do with myself at weekends. And we shall miss our fresh vegetables, shan’t we, Mary?”

Mary shrugged, but said nothing.

Annie stared out of the window again. “Would you mind showing me round the garden, Mr Benworth? If you have the time, that is. I wouldn’t know what to look for.”

He looked appealingly at his daughter who shrugged again. “I can walk back to Church Lane if you like, Father, and you can follow when you’ve finished here. Goodbye, Mrs Ashworth. I hope you’ll be happy at Netherleigh Cottage.”

Annie let Michael Benworth show her all round the garden, though much of what he said was meaningless to her. She had not really taken into consideration the fact that land could be productive, and could give them food, since she had never had a house with a garden before. By the time the tour was finished, she had made up her mind to seize this opportunity. “I wonder if we mightn’t come to some arrangement, Mr Benworth, to our mutual advantage?”

“Mrs Ashworth?”

She gestured to the garden. “Tom and I know nothing about gardening. And we won’t have a lot of time to spare to learn about it. If you would like to keep on with the gardening, we could share the produce and…” she had another idea, “my brother Luke could help you and learn how to do things.” When Benworth did not say anything, she added hastily, “I hope this suggestion doesn’t offend you. I shall perfectly understand if…”

To her embarrassment, he pulled out a large checked handkerchief and blew his nose, imperfectly disguising his emotions. “I don’t know what to say, Mrs Ashworth. Wouldn’t it annoy you to have me pottering about? A garden needs a lot of care, you know. I’d have to be here every weekend and sometimes during the week.”

She laughed. “There’ll be so many people around here, Mr Benworth, that I don’t think another will make much difference. I was thinking more of your time and trouble.”

He was in control of himself again. “To be frank with you, Mrs Ashworth, it would not be a trouble but a pleasure. And the produce would be very welcome. There’s nothing like home-grown vegetables.” He sighed. “Mary insists that we must start saving, try to buy a house of our own, however small, for the day when I’m too old to work. She’s right, I suppose, but I’ve never been much of a saving man. I’ve enjoyed my life, you see, enjoyed every minute. But she insists … and Mary can be a very determined person. I think she would approve of a businesslike arrangement about the garden. She’s even talking of looking for employment herself though there’s no need for that.” He broke off. “I’m sorry! I’m inclined to run on a bit, given the slightest encouragement. You should have stopped me.”

“I was interested,” Annie said frankly. “Besides, I feel – well, rather guilty at turning you out. You’ve been here for years.”

“It’s your house, my dear Mrs Ashworth. And your need is greater than ours. You father has told me that he and the children will be coming to live with you. I think your father is as lucky in his daughter as I am in mine.”

She bowed her head in acknowledgment of his compliment, liking the way he spoke well of his daughter, liking him better than she ever had before. “Then it’s agreed, Mr Benworth?”

“It is indeed, Mrs Ashworth!”

She did not approve of the warmth in his glance and added firmly, “This is purely a business arrangement, Mr Benworth. I’m not interested in anything beyond my business interests and my family.”

“That, Mrs Ashworth, is a waste,” he replied, “but I take your point. I shall not presume. And at least I shall still have my garden.”

“Then I’ll not detain you any longer today. You must have a lot of things to sort out in your new house.”

When he had gone, she wandered back into the house and exhaled with sheer pleasure. “Mine!” she said aloud. “All mine!”

Annie walked slowly round the kitchen. It was far larger than any kitchen she had ever had, because it had been a farm kitchen, with space to feed the family and farm hands as well as to cook in. The pantry was enormous. How could they possibly fill all those shelves? Leading off from the back of the kitchen was a small entry which led to the scullery and another large room that had once been the dairy. Well, she wouldn’t need a dairy, that was for sure, but the room was so big that it could surely be put to good use with so many of them to house. Behind that was a proper washhouse with a copper boiler. Wonderful! That would make things so much easier with a large family.

As she walked round them, Annie noticed the old-fashioned pump in the corner of the scullery. She ran her hand over the worn handle, then worked it up and down until water gushed out. Who knew where that water had come from? They would continue to boil everything they drank until the new Bilsden Municipal Water Company came into operation, and then they would apply to be connected to that. Dr Lewis himself was promoting that venture in conjunction with Frederick Hallam and some other dignitaries.

Annie smiled wryly. Such philanthropy! It wasn’t civic pride or concern for their fellow citizens that was driving most of the shareholders; it was concern for their own health. The richer people were just as afraid of dying as the poorer sort. Many families had lost someone in the recent epidemics and suddenly the things that Dr Lewis had been saying for years about sanitation and a clean water supply were being listened to.

Eyes narrowed, Annie studied the pump. Her son had nearly died in the scarlet fever epidemic and she had read about other types of epide

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...