- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

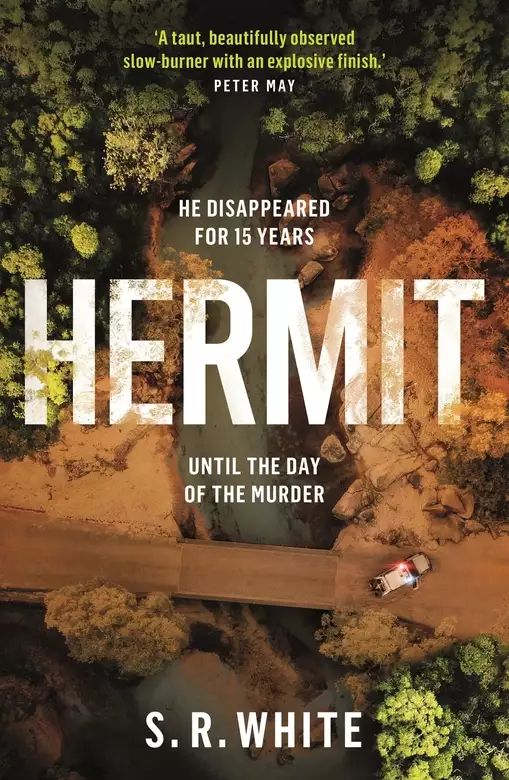

HE DISAPPEARED FOR 15 YEARS...SHE HAS 12 HOURS TO FIND OUT WHY.

After a puzzling death in the wild bushlands of Australia, detective Dana Russo has just hours to interrogate the prime suspect - a silent, inscrutable man found at the scene of the crime, who disappeared without trace 15 years earlier.

But where has he been? Why won't he talk? And exactly how dangerous is he? Without conclusive evidence to prove his guilt, Dana faces a desperate race against time to persuade him to speak. But as each interview spirals with fevered intensity, Dana must reckon with her own traumatic past to reveal the shocking truth . . .

Compulsive, atmospheric and stunningly accomplished, HERMIT introduces a thrilling new voice in Australian crime fiction, perfect for fans of Jane Harper and Chris Hammer.

(P)2020 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: September 1, 2020

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hermit

S. R. White

She could easily climb over this flimsy fence. Two strands of wire threaded between rudimentary wooden posts. It was nothing, would only take a second. She wouldn’t have to jump, really. She could just fall.

Maybe that would be better. Dana knew about trajectories: it was part of her job. If she landed on the middle rock – the one splitting two churning arcs of swift water – they’d understand it was deliberate. She’d have died in a manner that would demand close scrutiny. It would oblige them to sift through her life, looking for the explanation. Her emails and private documents, the contents of her safe, her diary. Everything would be exposed and picked over. She’d be dead, and then sliced open. Dana knew how far investigations could burrow; the kind of stones they turned over.

Whereas if her head struck the nearside bank, cleaving open her skull in a single strike, it might be considered an accident. There had been a lot of rain recently, and then this icy spell, so the edge was brittle. They might think her stupid or foolhardy, but they couldn’t prove she’d meant it. Perhaps then, they’d have less reason to pilfer the remains of her life and hold them up to the light.

A cold breeze slapped her face. Below her, a hawk skimmed the surface of the calmer water downstream. She watched its careless, immaculate wheeling and heard a keening cry through the misty air. Eucalypts on the far shore hissed; the blustery chill made her eyes water.

This was her Day. The day Dana granted herself full permission to think about all this; to examine it and ask if she found herself wanting. Each day through the year she kept it as locked down and hidden away as she could. Often, she failed. She failed because while the threat and the shame kept its strength, she waxed and waned: she was the variable. It was her reaction that stumbled frequently – she drifted with good days and bad, triumphs and disappointments, strong and weak. She tried to contain it adequately by allowing it one day of total freedom. For this Day alone, she deliberately and overtly questioned from every angle if she wished to live another year. If she was still asking at midnight, the contract was made: she would try to carry on until the next Day.

Last year she’d sat with the engine ticking over, safety belt unbuckled, staring at a large tree near her house. She’d fretted that the road wasn’t straight enough to gather a killer speed: she could ram into it, but she might still be alive afterwards.

Now she was shivering in an empty car park. She stepped back from the edge and squatted, hidden from any dog-walkers or joggers, her back uncomfortable against the car’s radiator grille.

This place – already a wound in her mind. Her memory reeled and spun, back to an identical day that changed her life. Being found at the foot of the falls would invite comparisons, make people reach for connections.

So she couldn’t jump. But she knew how to shoot.

Dana closed her eyes and counted to five. She held her revolver in both hands; it juddered as she struggled for breath. The barrel felt sharp on the roof of her mouth. It grazed and nuzzled, begging for the chance to release her. The trigger pressure on this weapon was hefty, but her thumbs squeezed consistently. Saliva oozed silently down to the grip.

Up: she must point up. She knew this. Shifting herself a little against the car, adjusting her posture, the memories skidded past her. Even though she fought to rein them in, they started to pulse faster, became subliminal. She closed her eyes again, squeezed a little more, feeling the trigger mould a groove in her thumbs. A silent tear caressed her cheek.

All Dana had to do was move her thumb a centimetre. Then it would be over. She’d never have to think about it again. There would be no more recriminations; no more hours glaring at her reflection, daring herself to own what she’d done. She’d never have to wake up again with a feeling of dread already drenching her. There must be something better, beyond this. If only she could do it. If only she had the courage. If only—

She could feel the phone vibrate despite her thick jacket. She hesitated, blinked hard and swallowed. The ringtone wouldn’t go away.

Dana hid when she could from loud noises, from bright lights, from squealing children and yapping dogs; from sentiment and kindness, from impatience and arrogance. She needed the flat line of quiet consistency. Usually she struggled through much of it beyond the gaze of others. Especially on this Day, she had nothing to give, and every moment since midnight she’d been a beat away from snapping. The pressure it created was volcanic, irresistible.

The ringtone still wouldn’t go away.

The gun bumped against her lip, numbing it on contact. Dana glanced at it, put the safety on and holstered. On her forehead was a cooling sheen of sweat; she felt clammy and nauseous under her coat. She stood uneasily and leaned against the car. In the windscreen’s reflection she loomed across the convex glass, pallid and desperate. Swearing, she fished out the phone and swiped.

‘Yes?’

‘Dana?’

Neither of them could hear above the roar of the waterfall. ‘Hold on,’ she shouted, and climbed into the car. Closing the door silenced the siren call of her pain. All she could make out now was her own stuttering breath. ‘Yes?’

‘Dana, glad I got you.’ Bill Meeks, her boss. ‘We have a dead body. Sending you the route. It’s kinda hard to find if you’ve never been there . . . Dana?’

She wasn’t ready. Wasn’t up to doing that. Her hand was shaking; she dropped her keys. ‘Isn’t Mikey on call?’

There was a pause. Did she come across as irritable, unprofessional? Why should she care either way? She wasn’t first on call today.

‘Yeah, he’s had to go to Earlville Mercy. His kid: stomach pains. You’re next cab off the rank. See you in twenty.’

He was gone before she could grunt any kind of reply. She looked back at the fence, and the void.

Someone just kept her alive, by dying.

Something didn’t want her gone. Not yet.

Jensen’s Store was down a rutted track about two hundred metres off the Old Derby Road, between Carlton and Earlville. Surrounded by tall pines, its solitude and serenity meant it made little sense as a commercial venture – there was no road frontage; the sign for it was half obscured by undergrowth and unlit. If Dana hadn’t been following instructions on the phone, she’d have overshot. Behind the building, forest stretched away gauzily.

The building itself was a lazily designed flatroof; wilfully utilitarian, it had a short overhang on a frontage that was mainly glass, speckled with fluoro-coloured posters of special offers. The parking area to the side was simply gravel and mud, mixed by spinning wheels and crunching boots. It was rutted and slippery in the despondent winter.

The emergency vehicles were parked herringbone along the approach lane: the area around the store was being tracked by a single-file line of uniforms, treading slowly as they scoured the frozen soil. The sun was above the horizon, but obscured below lingering mist which billowed lazily through the trees and gave everything a grey, ethereal wash. The occasional ghost gum stood out, a sharp vertical sliver like pristine flesh. Ferns glinted silently with crystalline frost.

To one side, two paramedics gazed at the gloom and drew testily on cigarettes. Their green smocked uniform had short sleeves; one seemed oblivious to the damp chill, the other yanked on the zip of a red puffa jacket. The hardier of them gave a raised-head acknowledgement as Dana passed; she couldn’t place him but nodded back in any case. Aside from the search team, she and Bill were the only cops available for now.

She snapped on some gloves at the entrance, where a wire basket offered two-for-one on rubber-soled deck shoes. When she started as a police officer, putting on latex gloves was a cop or a medical thing: now everyone did it, even if they were only heating a pastry. She checked her boots, tapping off some mud from her waterfall visit, and covered them with plastic booties that swished as she crossed the aisle. Reflexively, she looked for cameras: one over the checkout counter, and that seemed it for the interior. Maybe there were others hidden.

The police incident code had been ‘response to silent alarm’, so she knew that much. Little else. The alarm was one of those that covered the perimeter of the building, not internal movement. By the first aisle was a pinboard of local notices – grass-cutting services, a wooden aviary free to a good home and a ratty-looking old Ford Falcon to be gutted for spares. Above this, a gallery of the regular staff, who were all ‘looking forward to helping you’.

As she reached the third aisle, staff from the medical examiner’s office came into view, holding the stretcher. The two bearers had the same red hair and freckled faces, similar bloodless lips and consumptive countenance. She thought they might be twins and considered this an odd kind of family occupation. They paused automatically when they reached her, looking stoically up and forward to nowhere while she peeled back the zip on the body bag.

The victim’s face was puffy but looked oddly contented. The serenity of dead people never ceased to amaze Dana. Even those who’d suffered violent, lingering or painful demises: they all took on a repose of quiet satisfaction, as if a job well done. Somehow, in a small way, it gave her hope. They usually looked . . . pleasantly asleep.

The victim was maybe late thirties, and shaven-headed. His skull was broad at the forehead, giving him a massive and tipped-forward look even when horizontal. He was absurdly tall, with a large, bear-like jaw, and the collar of his T-shirt was ripped on one shoulder. With the body bag zip further back, Dana could see the entry wound. Just one, it looked like. No hesitation marks she could see, no splatter. The bleeding would all be internal. A smallish rose of dried blood on the T-shirt surrounding it and some smeared and bloody finger marks. Maybe a palm, too.

She guessed a blade of fifteen centimetres – it would need to be that long to pass the ribs and enter a major organ. Sometimes, only one wound spoke to expertise but frequently it was blind luck. In a melee of two people grappling for their lives there was little time or space to be forensic. The attacker might have stabbed purely to get the victim off them, or get away, or make them stop. Few people wielded a knife accurately – their efforts were often wild and desperate.

She zipped up carefully. ‘Thank you,’ she said quietly. The ‘twins’ headed for the door in lockstep.

Around the corner, Bill crouched by some blood droplets. There were several packets of rice behind him which had dropped from a shelf without breaking open. That appeared to be the extent of the physical evidence. A minor clean-up in aisle three: on a par with a kid spilling some chocolate milk. Even one pint of blood looked like a serial-killer rampage if it was sprayed around in a struggle; this was maybe ten drops.

Because of the solitary stab wound, Dana had expected the knife to be on the floor. A single stab in panic, in the midst of a scuffle, usually prompted the stabber to drop the blade and flee. At the very least, they let go in shock at what they’d done, or in disbelief that the person in front of them was dying. That didn’t seem to have happened here.

Bill glanced up. He would have been handsome when younger. In fact, she’d seen pictures of him up to his forties when he was exactly that. It was as if he’d signed a Faustian pact: breath-taking until mid-life, then your face will collapse. He looked almost a travesty of what he once was and she sometimes wondered – as someone who’d never experienced one – what it was like to have a definable golden era behind you, a period when your whole life glowed and others basked in it. Perhaps the juxtaposition was painful, or maybe it was comforting to have been something significant, once.

‘Hey, Dana. Sorry to take your day off you.’

She nodded non-committally, unsure exactly how much Bill knew about her motivation for taking this day off work each year. He knew it was an important date – half the station knew that much – but she didn’t know if his knowledge went beyond that.

Best not to ask. Best to avoid.

‘One stab wound,’ she noted.

‘Suspect is headed to the station. Knife is still someplace unknown – we’ll need a detailed finger search of the store, and maybe the undergrowth within throwing range. Unless the killer departed and took it with them. Patrol responded to a silent alarm linked to the station.’

‘A professional?’

Bill hefted himself up and rubbed the base of his spine. ‘I only saw our suspect briefly. No ID, nothing obviously incriminating. Couldn’t get a word out of him except his name. Nathan Whittler? Ring any bells for you? Nah, me neither. But, uh, dishevelled and disorganised at best. Could be a serial killer, for all we know. But no, I doubt he’s a hitman.’

‘Hmmm.’ Having nailed one last year, she didn’t believe professional killer meant anything beyond financial payment. That hitman had been an idiot, in a dozen different ways. But he’d been paid to do it.

Bill stretched out a kink in his back. ‘Dead man is Lou Cassavette, the store owner. There’s a sleeping bag, a home-electronics mag and some Chiko Rolls in the storeroom by the freezer section. Looks like he was waiting up for someone.’

‘Hmmm, breakfast of champions. CCTV? I saw the camera by the checkout, but’ – she glanced up and down the aisle – ‘I’m guessing we’re out of luck here.’

‘Yeah, only one other camera, in the storeroom. Overlooks the food-prep area out the back.’ Bill schlepped off a glove and scratched his forehead.

Dana took out a torch to see the blood drops more clearly. There was no way her kneecap would let her crouch down. ‘Mr Cassavette didn’t trust his own staff. He watched if they were dipping the till; he watched if they were spitting in the food. So maybe the suspect is an employee, or ex-employee?’

Bill nodded. ‘Way ahead of ya. I’ve got Luce checking for employment records as we speak. See these?’ He pointed at the bloodspot trail and she swung the torchlight back on them.

She followed the pathway with a silver beam. ‘Half of them in one place – where he was stabbed? Then he fell, or staggered, back a couple of paces, then they stop.’

‘That’s how I see it,’ Bill replied. ‘Stabbed here . . . fell back to here . . . and either he or someone else clamped something on the wound to stop the flow.’

‘Does our suspect have any blood on him?’

Bill stood again and smiled. ‘Oh, yeah. He has blood on his hands. Bent over the guy, hand pushed against the wound.’

‘Burglary gone wrong?’

Bill waved at a corner of the store. ‘Looks like he climbed in through that window over there. Professional, too. Put a bag on the windowsill so there’d be no marks, and bags on his shoes, too. He had a rucksack full of loot, but . . .’

Dana had reached the end of the aisle and could see the entry point. She scanned the floor less for prints, more for detritus like leaves or burrs; but there was nothing. The guy had entered smoothly and professionally, like he’d done it a hundred times before.

She turned back. ‘But?’

‘See for yourself. Weird.’ Bill pointed at a red rucksack to her left. It was well worn but still in good shape – in the gathering daylight she noted fresh dubbin recently applied to the seams. Through the open top she could see several paperbacks and two packs of mosquito repellent. Prising past these with a pen, she saw cans of beans and some chocolate bars. The rest was lost in the bowels of the rucksack. She’d get a full inventory later.

She ducked her head around the corner as Bill took out his phone. ‘Why was he stealing this? He could buy all this for next to nothing.’

‘Exactly. Why kill for that? Why be killed for that?’ Bill shrugged his shoulders and turned away to dial.

Dana took a glance back towards the exit and the preceding aisles. A couple of mountain bikes would be worth several thousand; she imagined fishing rods weren’t cheap. There were cigarettes for sale behind the counter, but they were secured by a roller door as per the law: she hadn’t seen any in the rucksack. The burglar seemed professional enough to enter seamlessly but amateur enough to steal cheap, largely unsellable items. The owner appeared ready to die for a minor point of principle – for stuff that wouldn’t even register on his insurance premium.

Halfway down the next aisle, splayed across the tiles, a packet of kitchen knives lay at an angle. The plastic lid had been ripped and one knife was missing. It seemed, from the indentation in the packaging, about the right size. She heard a murmur of Bill’s conversation, then his farewell to whoever.

‘Hey, Bill,’ she called over the top of the shelving. ‘Killer didn’t bring his own weapon?’

Bill leaned around the corner. ‘Yeah, looks pretty ad hoc, doesn’t it? Assuming that gap in the packaging turns out to be the weapon.’

She looked more carefully at the way the lid was ripped. It was still creased from the guy’s grip: rushed, but not frenzied. She wondered briefly why whoever did it had taken the third-longest knife and not the biggest one. Surely he would have wanted the best weapon he could get if the attack was spontaneous? And what had Cassavette done to make him feel he had to attack?

‘Did Cassavette have a weapon?’

Bill rocked his hand. ‘Maybe. Haven’t found one for him either. When Forensics get here they’ll search the whole place. But nothing yet.’

She realised she was wasting battery and switched off the torch. Golden light was now spearing in through the skylights on the eastern side of the building, glittering off the visible silver insulation in the ceiling. She could see cobwebs in the corners. Refrigerators hummed. The whole tone of the place was upbeat and direct – buy now, try this, grab one of these, limited time offer. All the colours on the walls, the packaging, the posters and special offers; they were lurid candy and cartoonish. Lonely, desperate homicide was a counterpoint.

‘So . . .’ Dana scuffed a foot against a kick plate below the shelving. ‘Guy comes in, ready to steal some beans, apparently. Gets halfway through; Cassavette makes himself known.’ She turned and went to the end of the aisle, pointing with the torch. ‘That’s our man’s escape route. I’m guessing all the doors were locked.’

‘Yup, and the lights were off. Someone opened the mains box and shut the power off before they came in.’ Bill joined her near a display of toys for kids of all ages. ‘Patrol switched it back on after they found the suspect and the body.’

‘This place doesn’t have back-up generators?’ Most did these days; the cost of replacing stock after an outage was horrendous.

‘They do, but they’re only wired to the freezers and refrigeration.’

Dana nodded. ‘So it’s totally dark. Cassavette comes out of his hidey-hole over there; the burglar’s only way out is back through the window he used. You have to assume Cassavette – either deliberately or accidentally – blocked the escape.’

‘Logical. He’s clearly been waiting up nights expecting a burglary; he figures help’s on its way because the silent alarm was activated when the window opened. All he has to do is contain the guy until the cavalry arrives.’ Bill went to the window and looked out at the parked vehicles. The uniforms were trooping back to three marked Commodores, disconsolate.

‘Yes. So why would the burglar go crazy? I mean, he looks like a pro – the forensic awareness, the very particular choice of what to steal. That isn’t random, it’s planned. So if he’s a pro and it’s all gone a little wrong, why fight your way out? Why so desperate?’

‘Maybe he’s on two strikes and this will send him away for a while?’ Bill turned back to face her and held his palms open. ‘I dunno. First sweep of the databases might tell us.’ There was a crunching of gravel outside. ‘Ah, proper search team.’

‘He was completely silent about what happened?’ asked Dana as they headed for the door.

‘He hasn’t said a word, as far as I know.’ Bill waved to Stuart Risdale, the head of the search team, who gave the thumbs-up as two others disgorged themselves from a darkened SUV. ‘Check that. The guy repeated one word.’

Bill turned to face Dana as the freezing air hit them from the doorway.

‘Guy said, “Sorry.” Several times.’

It was fourteen minutes’ gentle drive from Jensen’s Store, down a series of backroads, to the Cassavette house on the outskirts of Earlville. Dana had time to find a classical-music station on the way.

Earlville was considered the less prosperous of the ‘twin towns’. It had a sneering, fractious relationship with Carlton; a kind of sibling rivalry between orphans. Marooned in a region of forests, swamps and lakes, the two towns were merely background noise for city dwellers three hours away. Earlville thought Carlton was full of snobs and the wasting of public money; Carlton thought Earlville should give up its nostalgia for low-paid sweat jobs and join the modern world.

Most of the properties along the route were large ‘lifestyle blocks’: homes set back among the gums and myrtle, surrounded by pony paddocks. Faux-hacienda, with terracotta tiles replacing Colourbond, seemed the look du jour. Well-tended horses chewed thoughtfully near the road, steam rising gently from blanketed flanks. Twice she saw puffing teenagers hoisting tack on to a shoulder. Maybe the first thing in their adolescent lives they’d shown consistent sacrifice for; perhaps that was why their parents indulged it.

Many homes on this road had ostentatious stone entrances; Dana could tell which ones had electric gates, too. She’d noticed a while ago that shuttering off the outside world – and thus implying that everyone was a threat – was something that had seeped gradually from the city to Carlton. Score minus one for the famous Aussie egalitarianism, she thought: now, just like in so many other places, ‘others’ were a potential risk to be managed.

Bill was now at the station, debriefing the first-on-scene officers and prepping the suspect for interview. Lucy was driving in from home. Mike was on his way back from Earlville Mercy hospital and would ride as first assist to her investigation. Mike was a completer-finisher. Thank God: Dana had proper back-up.

Too early for commuting SUVs, she had the road largely to herself. Her pre-dawn excursion to Pulpit Falls kept pushing itself to the front of her mind. She had enough strength to shove it back temporarily, but she knew it couldn’t be contained.

Even murder was just a displacement activity. Investigating a killing staved off the force and resonance of memory, the crippling panic and catastrophic damage it caused. She’d granted her blind-siding depression one Day of freedom, and now she was compromising that. It would exact a price for the betrayal.

Her mind drifted a little: the Day seeped in. Slivers of a scalding blue sky long ago, scarlet blossom on cool grass, filigreed shadow and soap bubbles: she could almost feel the light that had sparkled in front of her. She shook her head. If there ever was a right time to consider that – and she didn’t feel there was – now was not it. She held the steering wheel tight and in her head she screamed, Focus. Work: work would surely drive out everything else. It always had.

The crime scene had been a series of pieces, not a coherent whole. If the killer was the burglar, it didn’t make sense – the burglary seemed like a professional job, and a professional would surely simply hold up their hands to the break-in and take the consequences. There would be no need to do anything more. Maybe Cassavette was the type to fly off the handle: How dare you steal from me?, and so on. But even then . . . the knife packaging. If the burglar had punched or kicked Cassavette and he’d hit something fatal on the way down: that would have been an understandable death. But when someone reached on to a shelf, tore open a pack of knives – selected the third smallest; that bothered her, too – and then stabbed: it was a degree, however small, of forethought that seemed at odds with an ad hoc altercation. There was something big beyond the obvious.

If it hadn’t been the burglar, the options would fan outwards from the life of Lou Cassavette. Family, business partners, friends, disgruntled former friends, people he owed, people who owed him, former lovers, spurned would-be lovers. She mulled over a list of possibles and how they might be narrowed down. She’d put Mike on to it. Dana was the primary and would pursue the prime suspect. Mike would look at other options and play devil’s advocate to whatever she was thinking.

As she got nearer the Cassavettes’ home the landscape changed. Lush gardens and majestic trees disappeared, replaced by scrubby lots and small industrial units. Roofs turned to scrappy and rust-flecked old Colourbond, neat verges dissolved, spangled concrete prevailed. The luxury of space disappeared and the average wage spiralled down to . . . mean. Next to a small strip of stores, high-set floodlights still illuminated the mist-draped parking area, where hooded skateboarders regularly outnumbered cars. A barricaded store in the middle of the strip promised to buy your gold for cash. To one side, a mini-mart offered to unlock any SIM card; on the other, an office window claimed that no cash was kept on the premises overnight.

She turned past a faux-stone entryway on to a new estate. It had been built to exploit the new freeway junction ten minutes away but had turned into a money-laundering opportunity for international crime. The banks now owned half the houses, and most of the rest were held by the courts and tax authorities: shells where it was foolish to fit copper pipes, or wiring. Earlville’s now-shunned mayor had opened the estate in a flurry of ribbons, flashbulbs and gurning optimism. He had been indicted but was still awaiting his chance ‘to put the record straight’. Actual owners were thin on the ground and either full of regrets or blessed by their endless and ignorant patience.

Low homes, more roof than brick, hunched on curved streets that must have looked lovely in the artist’s rendering. In the publicity the streets would have shimmered under blue summer skies, casually populated by hand-holding couples smiling as their offspring launched a toy yacht in the ornamental lake. In the chilly early morning of a weekday the streetscape was silent and bleak: kerbside holes awaiting ‘heritage street lighting’, front-yard saplings shivering and inconsequential. Roads finished abruptly, with vandal-proof fencing shielding vacant blocks. The developer hadn’t finished the street signs yet: it took three attempts down identikit cul-de-sacs to find the place.

Dana parked outside the Cassavette home as a grey BMW swept towards the main road, xenon headlights slicing the gloom. The driver held his phone to his ear, barking silently as he passed her. She took a deep breath. The Cassavette house was identical to the one each side; a series of three joined at the garage. A way of shoving smaller blocks on to each development. A country the size of a continent, she thought, and we’re ramming people together. The homes would each have the same floorplan, and neighbours would feel a bizarre sense of familiarity when they entered the house next door. The Cassavettes had forgotten to bring in the rubbish bin – it sat forlorn at the beginning of their path.

Uniform patrol hadn’t spoken to anyone yet; she would have to do The Knock. Some officers ran from that responsibility: she had an autopilot mode she could use. Telling the nearest or dearest had a rhythm, structure and etiquette she could understand, which both reassured and rescued her. Dana had done it twice before. Those hadn’t felt as difficult as they should have: she’d been cocooned by the recipient’s shock. Their emotional concussion allowed her to get away with her own reticence. They seemed to want to make tea or coffee or offer cakes; they rarely asked tricky questions.

She skirted around empathy because, primarily, it wasn’t helpful to the investigation. Close family were close enough to do more harm than good, to harbour grudges and nurture fears: they knew weak spots and moments to strike. Dana knew that well enough. Close family were therefore suspects until proven otherwise, and it hindered clear thinking to have already been sympathetic. Dana tried to strike a balance between humane and professional – if push came to shove, she’d always take the latter.

The door knocker was a metal lion’s head. When she used it, the door – being cheaper than the knocker it held – clattered in the frame. They threw these places up, she thought. Above the door, the soffit was already peeling paint.

The woman who answered was small, neat and oozed rapid capability. Dana made instant calculations. The woman would have fast-twitch muscles, she would eat and walk quickly

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...