- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

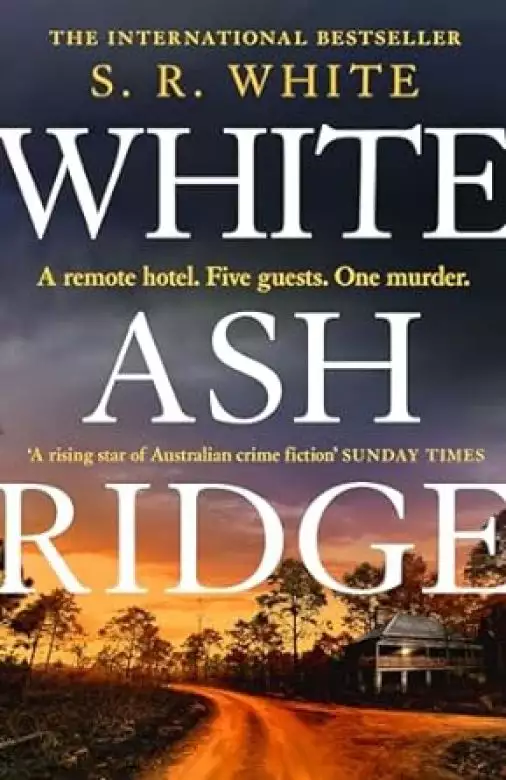

Synopsis

A REMOTE HOTEL. FIVE GUESTS. ONE MURDER.

A rising star of Australian crime fiction ' SUNDAY TIMES

'S. R. White is the real deal.' CHRIS HAMMER, author of SCRUBLANDS

During a broiling heatwave, the inner circle of a high-profile charity attend a critical meeting at White Ash Ridge, a small hotel nestled in the Australian wilderness.

As the temperature rises, a body is found lying in the thick bush, bludgeoned to death.

One of the four remaining guests is a murderer - but who, and why, is a mystery.

Detective Dana Russo knows the national spotlight will be sharply focused on the case.

The charity was formed when the founders' teenage son was killed after intervening in a vicious assault - sparking public outrage and a damning verdict on the police investigation.

But under huge pressure and with few clues - plus suspects who instinctively distrust the police - how can Dana unravel the truth?

Praise for S. R. White:

'A taut, beautifully observed slow-burner with an explosive finish' Peter May

'Original, compelling and highly recommended' Chris Hammer

'Gripping' THE GUARDIAN

'A fascinating case' SUNDAY TIMES

'It draws you in - and rewards with a truly powerful ending' HEAT

'This slow-burn novel catches light' THE SUN

'The story takes place over less than 48 hours but the pace is slow-burn, relying on considerable psychological depth...the denouement hits like a knockout punch WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN

'A dark and compulsive read' WOMAN & HOME

Release date: March 14, 2024

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

White Ash Ridge

S. R. White

It had wrenched every last drop of moisture from the foliage that flickered like tired embers; now it launched at him in a torpid, tropical wave. Heat like this didn’t belong here in Carlton: it was an outrageous intruder. He glanced around the clearing, which was helpless under the blue haze from sweltering eucalypts. A small hotel that looked more like a private home – verandas on all four sides, dormer windows blinking drowsily. Vestiges of timber industry heritage in the details: oversized rail sleepers trammelling a group of lifeless shrubs, a carved wooden sign to the guests’ car park, several former saw blades welded into an abstract sculpture and fading under a tawny patina. Two metal sheds near the trees: one was the size of a single garage, flanked by petrol canisters and a rust-mottled ride-on mower. The other was large, metallic and symmetrical in a russet hue – an American barn was the term, he dimly recollected. To his right a wooden pavilion, painted in Federation tones of cream and bottle green, that belonged in some nineteenth-century folio of a London park.

In the rotunda was a sallow, sweating man clasping a bottle of water. Next to him a young woman of maybe nineteen, a wet towel draped around her neck, dry-heaving towards a blue plastic bowl at her feet. The man seemed inured to her distress – to everything, in fact. He stared into the middle distance like a shell-shocked Digger, blasted by the Fates. The bottle slid gently from his grasp to hit the wooden decking, but he didn’t react.

She’d been the one to call it in: breathless, stuttering. They’d played the call to Rainer as he’d driven, blue lights spinning, to the scene.

‘A . . . I found . . . a body. On the path. By th— by the path to the falls. Sorry. Sorry. White Ash Ridge. The hotel. I – sorry.’

She’d stopped for the longest time, the operator’s patient questions ignored; some acidic scratching and the breeze in the trees the only soundtrack. Then –

‘Please. Send someone. Send everyone.’

After that the phone was seemingly grabbed and a man’s voice emerged, deeper yet more distant.

‘White Ash Ridge. We don’t know what’s going on here. We don’t know. We were – the kitchen. Not near enough to hear, you see, is it? They – they said it was some meeting or other. Discretion, they said. No media. They wouldn’t book until we promised that. But we never imagined – we should – please. Hurry.’

If either had noticed his arrival now, they didn’t show it. He put on his cap, his scalp itching after only a few seconds of dazzling sunlight. The temperature was maddening: it had climbed almost vertically for three hours after dawn and then flattened itself for the rest of the day. He recalled a year working in Darwin; how the locals swore that the build-up to the Wet season – a fierce corkscrew of blazing skies and pitiless scorching – had such a brutal effect on someone’s psyche that any crime should simply be excused. Any crime. Today felt like one of those Darwin days: callous, boiling, murderous.

The only reaction to the ticking of his cooling engine came from the cicadas, which suddenly erupted into an all-consuming screech. He tapped the radio on his shoulder and spoke softly.

‘Delta four, arrived at scene. Will advise.’

He wasn’t sure they’d heard him above the cacophony. He switched on his body cam and he’d begun walking towards the rotunda before he got the double-tap of static that told him message received. The whole clearing was throttled and airless, rendered supine by both the temperature and a sense that something had gone desperately wrong. Aside from the cicadas it was preternaturally subdued: there should be more people, more movement. Although, now that he looked up, he saw figures in the two upstairs windows: a man and a woman. They flicked the blinds and turned back inside as soon as eye contact was made. He was sure there was something familiar about them.

‘You’d be Rachel Dunbar? I’m Rainer, Constable Rainer Holt.’

He was glad to reach the shade of the rotunda and take a step up, although the change was purely psychological. The simmering air simply bounced off the earth into a darker space. The girl looked up at him slowly: she was drunk on the searing heat, soporific. Something had pulled the blood from her; it showed not just in her colour, but the startling effort that it took to stay upright. She held her hand in front of her as though it was missing a glass or bottle and then frowned, perplexed at her own gesture. She dropped her hand and swallowed.

‘Uh, yeah. Yeah, I am. This is my dad, Torsen.’

The man appeared unable to respond to his own name. Rainer followed his gaze, in case it was focused on something important. Torsen ignored the glinting patrol car and the people near him. His stare reached towards the bush that surrounded them, as though seeing it for the first time. A man who might have lived here for years, now finding the familiar to be terrifying. Rainer turned back to Rachel.

‘My colleague’s on his way, be here soon. Can you point me in the direction . . .’

Rachel buried her face in the towel, forcing patience on Rainer. He glanced around, bringing a professional eye – he sought entry and exit points, hiding places, signs of a struggle; anything damaged, out of place or jarring. There wasn’t much. The whole scene looked tired, even before this happened; a tourist destination on the skids. The adrenalin started to kick in. He could feel a fizz in his hands, an itch to do something. The police officer’s curse: always wanting to do, even when remaining still was the smarter option. Rachel rubbed her face with a slightly manic energy, then nodded.

‘Round the back of the hotel. There’s a path. Signposted to Pulpit Falls. About two hundred . . .’

That was it. She returned her face to the towel and Torsen continued to observe something no one else seemingly could. Rainer’s colleague Milo was coming from the east and couldn’t be more than a couple of minutes away. Even if his siren was on, it couldn’t defeat the cicadas. Rainer had to manage the logistics of being first and alone on scene.

‘Everyone else?’ he asked.

Rachel shrugged from under her towel, her voice muffled. ‘In their rooms, I suppose.’

She supposed? Rainer looked to Torsen, but the man was still stupefied.

‘How many?’ he asked her.

Rachel lifted her head carefully, like she was hungover. She squinted, mentally counting them off one by one.

‘Five . . . four now.’ She melted back into the towel and her shoulders convulsed.

It was hard to look away. People could exhibit all sorts of grief but still be guilty: the tears of regret, self-pity or malice. The killer – assuming there was one – could still be on the scene, could be right in front of him. He didn’t want to leave these two, but time was sliding forwards. If there was a body, evidence could be disappearing while he stood and acted concerned.

Rainer got a burst of energy and moved towards the hotel. He’d need to secure the area around the body; it was almost certainly out of sight from here and so he’d have to wait until Milo was available to control the clearing. But before that he needed to get everyone accounted for, and get them away from myriad electronic devices at their disposal. Phones, cameras, laptops: they were both angels and demons for a murder investigation.

He stepped through the open door into the hotel foyer, such as it was: little more than a hallway with a tiny alcove under the stairs for a desk. The work surface was awash with paperwork and local tourist leaflets, seething like a tide against the computer and the EFPOS machine. Multiple plugs overworked the sockets and looked like an imminent tragedy. Dust motes wheeled in the sunlight. The building felt silent and empty, as though everyone had left, rather than staying quiet in their rooms. The place had no sense of busyness, nor of relaxed repose.

The room that swept away to the left was bare and under-designed. Its utilitarian easy-clean carpet, magnolia walls, plastic chairs and stackable tables contrasted with the hallway, which had a rich burgundy wallpaper, brass wall lights and two exposed beams. Basic business function jarred against historic home-from-home. Ahead, stairs to the first floor were bookended by unnecessarily large newels, part of a hallway centred on a chandelier light that was probably on permanently. To his right was what Rainer was really looking for.

He set off the fire alarm with a jab of his baton. The glass poured to the ground in a delicate arpeggio that he couldn’t hear above the piercing noise. He was gambling that the system wasn’t directly connected to the fire department. He didn’t want to explain himself to ramped-up fire crews, who’d been twitchy about any semblance of smoke for the past six weeks. Other parts of the country already had infernos tearing through isolated landscapes. This hotel was basically kindling surrounded by kindling: emergency crews would be hair-trigger about a blaze starting here.

He poked his head out of the door to reassure Torsen and Rachel that their family business wasn’t burning to the ground. But they sat bereft, as if the siren had never happened. The noise split the air and acquired a rhythm of rise and fall; behind it, he swore he could discern the engine of an approaching car climbing the hill. He heard an upstairs door open, then close. Another opened, longer this time, then closed. He waited. Six more times with the same noises. If this was a real fire they’d be halfway to dead, while they told themselves it was nothing and they’d look a fool if they rushed downstairs. Many people died in hotel fires not just from smoke inhalation but from a vague fear of social embarrassment.

Eventually, murmured voices and the clacking of door locks. Four figures made their way to the top of the stairs as a tight group. They bent slightly at the knee and squinted down, as if the flames would only be genuine if they were visible from there. Instead they saw a tall, slim police officer glowing with impatience. They hesitated.

‘Everyone. Down here. Now.’

They looked at each other. Someone had to be first to comply. One of the two women – the elder by a decade or so – made the first move. She came down the stairs smoothly, like a dancer: her steps were fluid and controlled. Behind her the older man traipsed, the younger man flitted on springy heels, the younger woman stomped heftily.

‘What’s going on? Is there an actual fire, or did you –’ The older woman baulked at the sparkling glass shards at Rainer’s feet. Despite the belligerent glare, her voice felt like warm honey.

‘No, there’s no fire. I need you all to step outside immediately.’ Rainer indicated the door, then turned back. ‘Does anyone have a mobile on them?’

All four nodded. Of course they do, he thought; who doesn’t? Who goes anywhere without it clamped to them, somehow? Backside, jeans pocket, handbag, even on the bicep. That would be part of their delay in reacting to the alarm – grab the phone, maybe turn on the camera, perhaps a recorder. Possibly, message the world.

He reached for a waste bin from below the computer and tipped the scrunched paper on to the carpet. He held the bin and waggled it. ‘All the phones in here, please.’

The two younger ones reached for their pockets, but the older woman lifted a hand and they stopped instantly. The older man began slowly shaking his head.

‘Why, exactly?’ asked the older woman. Her hip-throw would have been flirty in different circumstances. She had dark eyes that held his attention.

‘Because I said so. Phones, thank you.’

The older man leaned forward slightly and spoke over her shoulder. ‘Keen . . . leave it.’ Less a growled warning, more a hushed plea for diplomacy.

The woman frowned, sighed impatiently, and flipped her phone from back pocket to bin in one motion. Fluid again, he noted. The other three complied less gracefully, but with more grace. Rainer stopped for a second and mentally reassessed the woman’s face and the man’s quiet pleading.

Keen. She was Keena Flynn. He was Max Flynn.

Jesus Christ, thought Rainer, Dana’s going to flip. The case had just become ten times more difficult. No detective really wanted a crime the whole country would talk about every day – Dana was now stuck with exactly that.

‘Come with me.’ Rainer turned and moved out on to the veranda. They trailed behind him unwillingly until they were in the centre of the clearing, subject to the relentless furnace. A voice behind him was slightly plaintive, wary. The younger woman, he was sure. ‘Where’s Ryan?’

He ignored the question as he saw Milo’s car squeal to a halt in the parking area. Even Torsen looked up momentarily and then, apparently noticing Rachel for the first time, curved an uncertain arm around her shoulders. She was still buried in the towel but the dryheaving hadn’t resumed.

Milo got out and came towards him. They met thirty metres from the group of four. ‘Sorry, Rainer, bloody road crew out on Hackett’s . . . anyway, what do we have?’

They shook hands and Rainer cast another glance around the scene. It didn’t feel any more benign than when he’d arrived: it sulked under the heat but there was currently nothing to indicate a struggle, let alone a dead body. He checked back to see if any of the four were chatting: they mooched around silently and scraped the dirt with their shoes.

‘Not sure, yet. Pretty bad, I reckon.’

Milo nodded. ‘A body, Control said?’

‘Yeah, maybe. Let’s hope not. I dealt with a road accident last month and I still see the look on that dad’s face every time I go to sleep. Hard to say what’s going on here.’ He nodded towards the rotunda. ‘Those two are stunned by something major’ – a glance at the other group – ‘but these are behaving like nothing’s wrong. Look, I want you to take the Gang of Four to that barn over there, please. I want them sitting well apart from each other and no, repeat no, comparing notes. Stay with them, make sure of it. I’ve got their phones: no one gets theirs back until we say. If they’ve got another one on them, confiscate it immediately.’ Rainer nodded to himself. ‘I think we might have a major crime scene here, Milo, and I want everything and everyone separated out until the detectives are happy. Okay?’

‘Sure.’ Milo reached past Rainer and beckoned the small group.

‘Oh, and Milo? Radio on earpiece only, eh? Let’s not give anyone a helping hand.’

‘Gotcha.’

Rainer took a deep breath. A dead body and the Flynns.

Two concepts that should never mix.

Not again.

Rainer watched the five of them head for the barn, Keena Flynn giving him another glare as they passed. He glanced back quickly to the rotunda and headed for the path. As he passed the entrance of the hotel he stepped up, put the bin of phones on the glass shards from the alarm and pulled the door closed. As he stepped off the veranda the alarm sobbed to a halt, unexpectedly soon.

The back of the hotel had an extended deck, reaching out like a ship’s prow over the incline. The ground-floor windows reflected glistening leaves and sparks of sunlight. The sky was that impossible blue he’d only seen in Australia: not just cloudless but endlessly scalpel-sharp. The kitchen was at the back, along with a dining area and the rear end of the conference room he’d seen earlier. Not counting the windows, there were four exits from the back of the hotel to the deck and the bush beyond. The trees were too near for comfort, he thought. The local council were big on pristine wilderness and biodiversity, but this meant foliage crept too close for a hose to fight off the flames. The deck had some white plastic sun loungers – Adirondack chair meets Big W – a stowed large parasol and a tide of fallen leaves that someone had swept but not cleared. He glanced up at the roofline. Three windows faced this side from upstairs; he didn’t know much about the layout but it was likely one or two were bedrooms. They might have seen something. Everything. Assuming there was anything to see.

He looked in through the kitchen window. The emergency call had implied Rachel and Torsen had been interrupted while in the kitchen; it wasn’t clear how they’d learned of a body under those circumstances. Rainer expected to see half-sliced lemons, or a bowl of dough and flour, or a wire tray of tarts left to cool. But there was nothing on any worktop, no sign that any appliance was on. He could see the swipe marks where the worktops had been cleaned, all the knives gleamed on the wall, the lights were off. Everything looked shut down for the day: presumably, before the emergency call was made. Because no one would make that kind of call, then set about cleaning the kitchen knives. Would they?

Keena and Max Flynn. He should have picked them straight away; when they were walking down the stairs, or even when he saw them briefly at the upstairs windows. He’d seen their photo a thousand times – everyone had. He hadn’t recognised them purely because he hadn’t expected to see them: they were so out of context it had thrown him. They both lived in the city, he knew that. Quite why they were down here in Carlton was a mystery. And a worry. They usually moved about, whether they wished it or not, with the imminent prospect of a posse of journalists and photographers on their trail. Keena, especially, was ubiquitous: a speech to the National Press Club, or launching a conference, or coffee with the Prime Minister. When the detectives arrived he’d need to tell them about the Flynns early on. Dana Russo hated that stuff; not least because the district commander, McCullough, refused to get involved with the media and left it to the lead detective.

The trees seethed momentarily, before drifting back into their crackling lethargy. The sign to Pulpit Falls was at shin height, next to a small light topped by a miniature solar panel. The path began broadly enough but quickly filtered into a ridge of powdery soil as wide as a football. He kept to the low-slung undergrowth a metre to the side; he could see signs of disturbance to the path but it was hard to judge details. At the very least, he speculated, there should be Rachel’s footprints downhill and up again. The ones coming up should be further apart: she was probably running, maybe screaming, by then.

He noted how quickly the slope eradicated any sight of the hotel; just thirty metres in and it became green and silent. Rainer scanned the way ahead, conscious that if someone was waiting then he was a simple target. He drew his gun and edged further down the hill. The path changed quickly into a series of zigzags that wended down the slope into a shadier glade. It was harder staying away from the path now; the gradient was steeper and the vegetation at knee height was tenacious. He could feel his shirt sticking to his arms. He had no time to look for snakes and simply hoped his noisy bumbling was keeping them away. The heat didn’t disappear as he descended, but felt as if the canopy shredded it into a kaleidoscope of light. Shimmering clouds of flies hovered nearby.

He wasn’t a good judge of distance and couldn’t be sure if Rachel was any better: two hundred could be anything between one hundred and four hundred metres. This far into the trees no one would hear anything from the hotel, or from the valley further ahead. Get thirty or forty metres off this path and you could hide for ever. He became conscious of his height, his lack of experience in this terrain, his vulnerability. The trees rustled occasionally but the overwhelming sense was of unnatural stillness. He breathed out slowly. It didn’t help. Fifty metres further on, he turned past the rare diagonal shape of a half-fallen tree.

He saw the body before he got near it.

His heart lurched. Training and process would take over now, but the icy stab of a life cut short had already gone through him.

The first thing he wanted to do was rush to it, check for vital signs. Instead, he paused for at least a minute, trying to take in anything that might be useful later: flattened grass, or any colour outside the palette of tired leaves, baked soil and heat-riven bark. Nothing. Everything looked as it should, but felt completely wrong.

Now he moved carefully towards the body, trying to spot any deformation, kink, twist, snap, anomaly or damage to the undergrowth. He reached down to touch the wrist. No pulse. Anything else he did here and now could only harm the investigation. He took a piece of chalk from his pocket and marked his way on successive trees as he went back uphill. This route would form the safe entry for investigators and techs alike: the path they took that was least likely to damage evidence. At this point, everywhere was potentially useful.

Extracting a roll of tape from his pocket and holstering the gun, he guessed at a thirty-metre radius from the corpse and began clomping through the underbrush, winding the yellow tape around any suitable branch as he went. The leaves snapped under his foot, baked by the last few weeks of scalding blue heat. It was unusual for Carlton to be on edge about bushfires, but they all were: an underlying jaw-tightening tension to everyday life, a jittery glance at the horizon, a double-take at any blemish to the azure sky. The gradient was shallower here; he could get a rhythm to his movements. As he crossed the path again he looked south, towards the waterfall: no sign of footprints. It took several minutes to complete the circle.

He wondered if anyone else had arrived at the hotel. With any luck Milo had contained the four in the barn without any chance to compare, intimate or intimidate. Rainer should have told Rachel and Torsen to stay put. He cursed himself.

From a pouch in the small of his back he extracted a webcam the size of his fist. He clipped it to a branch, looking west over the crime scene. He had to leave here and go back to the hotel; he had no idea when he’d return so he thought this would give a modicum of security. If someone came across the corpse – or returned to it – they’d have a fair idea of who’d done so and what they did.

Brutal crime scenes could also be serene, and vice versa, he’d learned. Dana and Mike had taught him to trust his instincts, but also that he’d need to yield to them. He took a few seconds to close his eyes, empty his mind and let his senses drift. No particular smell: it was too dry for scent to coalesce and all he could take in was ambient eucalypt. No sound but the trees: too far from the road or hotel to hear human activity, though a voice might travel down the slope. Everything had lost texture and become harsh and metallic: it all felt dehydrated and flammable.

He opened his eyes and mentally described how the scene seemed to him. Something in the ether suggested that this place had never been crowded. Two, maybe three people, at most. Intimate, personal, close up. He reached for the specific atmosphere that said life had been extinguished here. Sometimes, Dana had told him, it could be sensed; a tangible difference caused by death. This time, nothing.

He glanced around again for signs that anyone had been here recently. He couldn’t see any greenstick branches, or torn cloth or dropped glinting object. All he saw was a sweltering forest; relatively sparse foliage, parched trees and a floor of brittle debris – bushfire fuel ready to go.

Before he left, he took a look back at the body. White trainers, not quite box-fresh. Jeans that tapered to a boot-cut: on-point and taking a pride in appearance. A tan belt that might have been snakeskin. A blue T-shirt, rucked up enough to show good muscle tone and honeyed skin: someone who worked out and spent some time outdoors. The head was hidden from view, but he’d glimpsed thick brown hair when he’d checked the pulse: male, maybe thirties or late twenties.

As he rounded the hotel veranda he could see that Rachel and Torsen hadn’t wandered. She was sitting back now, slurping from the water bottle and using the towel to wipe her brow. Torsen sat bolt upright, hands on his kneecaps, like a stoic old man waiting to be called back into the oncologist’s office. Rainer could see Milo’s back over at the barn: his colleague stood barring the exit. The cicadas had dropped back to merely loud.

Rainer heard engines approaching. He nipped into the hotel hallway, located the guest book and took a photo of yesterday’s page. Yes, he confirmed, definitely the Flynns. Crap.

Dana Russo’s car came to a slow, crunching halt in the shaded part of the driveway, deliberately blocking in all the cars in the guest parking. She’d been perceptive enough in her first few seconds on the scene, he realised, to close off an escape route for someone potentially involved. Neither he nor Milo had thought to do it. Behind her, a pair of Forensics vehicles halted with two wheels on the verge.

Thank God, he thought. He realised his jaw was grinding, his fists were closed tight and his breathing was intermittent. He could let go now. It struck him that he was years away from being capable of doing what Dana was about to do – take charge of a murder investigation.

As a freckly redhead, Milo was glad to be out of the direct heat, but his relief was tempered by this new babysitter role. Especially looking after Keena Flynn.

He’d recognised her straight away, before he’d even clocked her husband. Milo was an NRL tragic, so much so that he’d actually seen Max Flynn play one of his few professional games of rugby league. Nuggety, determined, but limited; that had been Milo’s view, and he’d seen plenty of halfbacks playing reserve- and first-grade. All the same, Keena’s celebrity now more than eclipsed any brief fame Max might have enjoyed two decades ago. The body language of the four as they’d trudged to the barn said that she was the celestial body, the others were in orbit.

Milo himself had, like many people, something of a crush on Keena. Those images of her at the funeral – simultaneously broken and elegant, her delicate cheekbones and an unconscious ability to present the right angle to every lens. Tons of newsprint had reflected on the ‘inappropriate attraction’ Keena presented: desirability in the midst of her numbing grief. Milo didn’t think the two were opposites. In fact, he felt they went together. Keena’s shock and vulnerability in that moment were part of the appeal; they softened what could often be aggressively sharp edges to her character, they added to her enigmatic beauty. She wasn’t unaware of it, either, thought Milo. He’d heard she regularly used image consultants for key events: she understood that her appeal was influential. At best it created publicity for her cause, but at worst it was vanity and ego indulgence. There were plenty of supporters for each view. If Keena objected to the objectification, she was more than prepared to use it; that was another ambiguity she presented.

The barn didn’t run as deep as it had looked from the outside, but he managed to sit all four on plastic milk crates in a shaded area to one side, about three metres apart. Aside from Keena and Max, the other two seemed an incongruous pair. The man was straight-backed and almost noble, with dark brown skin and anxious eyes that darted constantly. He held himself high but, thought Milo, without conviction, as though he were a schoolchild eager to impress on the first day. He was the only one dressed for business, with a crisp white shirt and dark chinos. The woman was more heavily set, with sensible court shoes and a long skirt that must have been murder in the heat. She focused on the floor, fidgeting with a hair grip. She seemed determined not to stare at Keena.

Milo kept one eye on the group while he watched the hotel. The two over at the rotunda barely moved – they’d been rendered helpless by events. Rainer was hoisting himself up the last of the slope and around to the front of the hotel, stopping briefly and dipping into the foyer. He was a quick thinker who explained himself well; Milo liked him. Word was, he was destined for detective if Dana and Mike could get him on the requisite courses. The trees looked spent and the grass beyond saving: it was dissolving into the ochre dust beneath it. The heat didn’t have anywhere to go in the barn; it draped itself over them and gave everyone a languorous irritability.

Keena sighed. ‘What the hell’s this all about? We’ve got important business going on and we need to get back to it.’

Milo deliberately looked away, as though her words were background wash. Keena glared for a moment, then changed tack.

‘When do we get our phones back?’

Milo folded his arms and half watched Rainer walk towards a recently arrived Volvo. ‘When the lead detective has finished with them.’

‘Don’t you need a warrant for that?’ The question came from Court Shoes. Crisp Shirt tutted.

‘We’ll have one before we start looking at the phone data,’ said Milo. ‘Close Proximity. For all of you.’

Keena grunted. ‘I always said that was a little slice of fascism, Close Proximity. We don’t know why you’re detaining us and yet you’re going through our phones, our personal stuff.’

‘Not mine,’ declared Crisp Shirt. ‘Got a fingerprint pass on it. I told you all to do that. But no, don’t listen; do your own thing, see what happens.’

‘Enough talking.?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...