- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

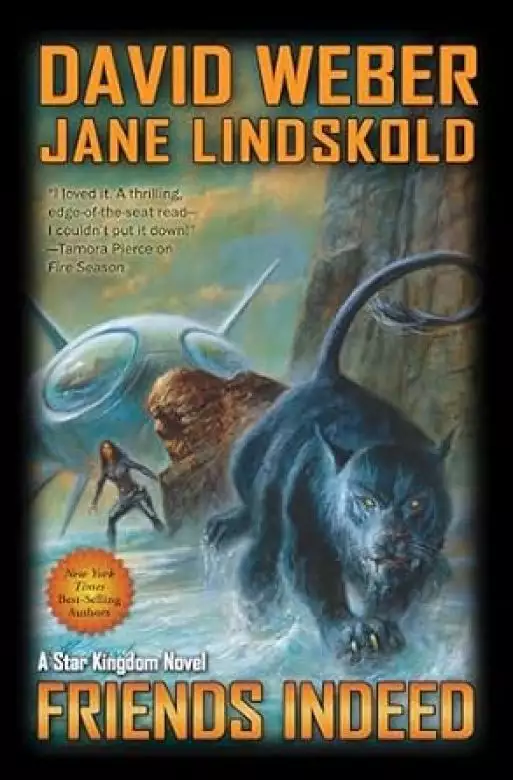

A NEW NOVEL FEATURING STEPHANIE HARRINGTON IN HONORVERSE PREQUEL SERIES

THE TROUBLE WITH TREECATS

Stephanie Harrington didn’t discover treecats—they were indigenous to the planet Sphinx, a colony of the tiny Star Kingdom of Manticore. But at age ten she was the first human to bond with one. Now, almost 17, she is the species greatest champion.

To the rest of the human galaxy, if they are known at all, they are recognized as tool using, socially organized, fuzzy little creatures, with no known method of communication—who also happen to be fierce hunters. But are they sapient…? Because if they are, that would have all sorts of repercussions for the families who have settled on Sphinx, the Harringtons not the least.

There will be winners, and there will be losers. And Stephanie is there to make sure the treecats don’t lose out.

But Stephanie, the treecats, and Sphinx itself may be caught up in an even greater conspiracy than the one to help the fighting ‘cats survive, one generations in the making.…

Release date: March 4, 2025

Publisher: Baen

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Friends Indeed

David Weber

PROLOGUE

“I must say this is…an unexpected surprise,” Duncan Harrington said as the well-dressed man stepped into his office. Then he smiled. “On the other hand, I don’t suppose it could be a surprise if I’d been expecting it, now could it?”

“No, I suppose not,” the other man said as he crossed the comfortably cluttered office. Duncan stood, extending his hand across his desk, then waved to the comfortable chair in front of it. The visitor seated himself and looked around.

“I swear, Duncan, you’ve added at least two more layers since the last time I was here. What is it about you and hard copy books? Photons pack an awful lot tighter—and neater—than this.”

He waved one hand, indicating the old-fashioned, over-packed bookshelves, and Duncan chuckled.

“Look, I’ll admit e-books are a lot more convenient. Like you say, they pack tighter, and you can find things in them a lot faster, for that matter. But that’s sort of the point. I enjoy the hunt and the thrill of the chase as much as I enjoy pulling down my prey at the end of the safari. Besides, some of these”—it was his turn to wave at the bookshelves—“are so old I probably couldn’t find them in an electronic format even if I tried!”

“Well, I’m afraid you’ll have to put them into storage for a while,” the other man said in a more serious tone, and Duncan straightened in his own chair.

“I will?” He cocked his head. “Why would that be, Abner?”

“Because something needs looking into, and you’re the best man for the job, for several reasons. I know it’ll be inconvenient, but we’ve come up with a pretty fair cover—who you are and what you do for a living helped a lot there. And besides,” he smiled, “I think you’ll enjoy the trip.”

“What trip?”

“The one to visit your cousin Richard in Manticore.”

“Excuse me?” Duncan blinked, but his guest only looked at him with that same smile.

“I thought the decision had been made to let that part of the line go,” Duncan said after a moment. “And, to be honest, I still think that’s the right choice in his case. For that matter, if we were ever going to tell him, we should’ve done it before he and Marjorie left Meyerdahl.”

“I didn’t say we were sending you to recruit him, Duncan.” The other man shook his head. “The truth is, the selection committee agreed with your recommendation at the time, and we haven’t changed our minds since. It’s a pity, since he’s at least as smart as you are, but there’s not much question you were right about how he’d have reacted if the Alignment approached him.”

“I’m relieved to hear that,” Duncan said. “Believe me, nobody could have wished he’d been a more…receptive candidate more than I did, but he never could have accepted such an enormous breach of the Beowulf Code. That was his mother in him, I’m afraid. Aunt Gabriella was downright fanatical about that.”

“And it didn’t help that the selection group had bypassed his father, either.” The other man nodded. “Your evaluation weighed in the decision, Duncan, but it wasn’t the decisive factor. The assessors agreed completely with you.”

“Then why am I going to visit him?” Duncan asked dryly. “I’m assuming the Powers That Be can come up with a reasonable pretext, but clearing it with the University won’t be a trivial challenge. You do realize that, don’t you? They’re not real crazy about letting their department chairs go haring off across the galaxy just to visit family.”

“It won’t be a problem with the University,” the other man assured him. “I’m meeting with Chancellor Atwell after you and I are finished—officially, this is just me dropping in on an old friend on my way to my appointment with him—but that’s for the public record. The truth is, we’ve already planted the seed, and Atwell’s ready to grab the proposal and run with it as soon as we officially drop the credit.”

“So the Foundation’s fronting for this?”

“In a manner of speaking.” Abner Portnoy sat on the Board of Directors of the Prometheus Foundation, whose charter to constantly push the bounds of human knowledge was an excellent cover for his real purpose in life. “For that matter, I didn’t even have to concoct a pretext to get the rest of the directors on board. It’s more a matter of answering a help-wanted ad or sending a rescue mission than anything else, but this has the potential to completely reorder our understanding of how brains and communication work.”

“I know you like your little mysteries, Abner, but could you sort of come to the point?” Duncan shook his head. “You know I’ll accept my marching orders, whatever they are, when you finally get around to telling me about them. But I do have a lecture coming up in about forty-five minutes, so if you could see your way to explaining what those orders are, I’d appreciate it.”

“Darn, Duncan—you’re no fun at all!” Portnoy chuckled, then raised his hands in surrender as Duncan cocked a fist and shook it in his direction. “No need for violence!” he said, lowering his hands, and his expression was far more serious than it had been. “The truth is, your Cousin Stephanie’s the real reason for the trip.”

“These ‘treecats’ of hers?” Duncan’s dark eyes narrowed. “Is that what this is really about?”

“Of course it is.” Portnoy leaned back, crossed his legs, and shrugged. “Your family does seem to produce a lot of overachievers, even for an alpha line, doesn’t it? Discoverer of a previously unknown tool-using species when she was only eleven. God save the galaxy from what she’ll be doing by the time she’s thirty!”

“The last time I saw Stephanie, she was about nine or ten T-years old,” Duncan said. “Still, I can’t say I was astonished by her accomplishments, especially—I might add, with all due modesty—with me as an example.” He buffed his nails on his sweater and blew on them, then grinned. “What’s that old saying about the apple not falling far from the tree?”

“She does seem to be a credit to her genotype…even with you as ‘an example,’” Portnoy observed. “Has she written you about her new friends?”

“Like I just said, the last time I saw her she was about ten. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if she’s pretty much forgotten about me by now. But, in answer to your question, no, she hasn’t. On the other hand, I’ve had several letters from Richard, and he’s clearly excited about them. We don’t write as much as we probably should, given the transit time; it’s not like there are any direct trade routes between here and Sphinx, so the mail service isn’t exactly reliable. But I’ve got at least a couple of megabytes from him about their physiology, their apparent habitat requirements, and their diet. In that respect, I’m probably better informed than anyone else on Meyerdahl, although at this remove that’s not saying all that much.”

“What’s he told you about their social organization? Or about their intelligence?” Portnoy asked a bit more intently.

“Not as much. In fact, not much at all beyond the fact that he clearly thinks they are sapients.” Duncan frowned. “The truth is, he’s been…I don’t know. He seems almost guarded, if that’s not a silly verb, when he talks about that side of them.”

“It’s probably exactly the right verb, actually,” Portnoy said in a much more serious tone. “Have you been keeping up on the literature about them?”

“What literature?” Duncan raised both hands. “There’s been a certain degree of speculation, but Manticore’s over two hundred and sixty light-years from here, Abner, and we don’t have any direct academic links or partnerships with the Star Kingdom, you know. Essentially, what I’ve seen backs up Richard’s belief that they are, indeed, tool-users with a sophisticated social organization that—in my opinion, judging from what I’ve seen at this range—clearly moves them into the category of true sapients. I can’t begin to tell you where they’d place on the scale, given the third- and fourth-hand reports I’ve seen, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if they’re in the running to be named Sphinx’s native sapient species. Which, I’m sure, would have all sorts of repercussions.” He grimaced. “Richard’s mentioned Barstool in a couple of his letters. To be honest, I figured that was probably the reason he’s not waxing more fulsome even to me. Keeping them under the radar until their supporters are in a better position to prove their sapiency is exactly the way his mind would work.”

“And you never wanted to go out and see for yourself, firsthand?” Portnoy asked.

“Of course I did! But unless the University was ready to grant me at least a two and a half T-year sabbatical—or some magical sponsor turned up to underwrite a grant to fund a University-sponsored research trip—there was no way to justify it.”

“Well, it happens the Prometheus Foundation is prepared to underwrite that very grant,” Portnoy told him.

“Why?” Duncan’s eyes narrowed. “What, exactly, does this have to do with understanding brain function or modes of communication? My impression from the literature is that they don’t have a ‘mode of communication.’ In fact, that’s undoubtedly the biggest single bar against accepting their full sapiency. They don’t have a spoken language, they don’t use sign language, and there’s no real evidence of any olfactory mode of communication, either. Which,” he made a small throwing away gesture, “seems very odd to me, given what little I’ve seen about their social sophistication. You don’t get that kind of organization and task sharing without some way of communicating at least basic concepts with your fellows.”

“Exactly. Look, we don’t have any sources or members in Manticore. To be brutally honest, the ‘Star Kingdom’ is at the ass end of nowhere, as far as the galaxy at large is concerned. But that doesn’t mean we don’t hear things, and one of the things we’re hearing is that they may be telepathic.”

“Telepathic,” Duncan repeated carefully, then snorted. “And how long have we been chasing that particular grail without ever once scientifically demonstrating that it’s even possible?”

“A long time,” Portnoy conceded. “And I don’t blame you for feeling a little skeptical. For that matter, you’re not the only one who thinks it’s a long shot. But if it is possible, and if we can figure out how to replicate it in humans, it could be a game changer, Duncan. Think what we could do with that kind of advantage!”

Duncan leaned back, looking at him, and despite his doubts, he had to admit Portnoy had a point. But still—

“Can I ask just who we’re hearing this from?” he said after a moment.

“The most interesting thing, in a lot of ways, is that it’s obvious from your reaction that we’re not hearing it from your cousin. That may be significant, given what you said about Richard’s worries about Barstool and the Amphors. Of course, it may also mean there’s nothing to it, which is why he hasn’t mentioned it. But at least one report from the first wave of xeno-biologists and anthropologists suggests the possibility as the best hypothesis to explain the degree of communication you were just talking about when they don’t have a way to communicate that we can detect.”

“And that report would be from whom, exactly?” Duncan shook his head. “I’m pretty sure somebody here in the Department would’ve heard something about it if there were any kind of supporting evidence.”

“Probably not, since it was from one of Radzinsky’s graduate assistants.”

“The Radford Center Radzinsky?” Duncan raised both eyebrows.

“I see you’ve heard of the lady.”

“Of course I have. We travel in the same academic circles, unfortunately.”

“Not a huge fan, I take it?”

“You take it correctly,” Duncan said flatly. “You know how I feel about the flaws in the sentience scale, and despite her reputation—which, admittedly, is huge—Cleonora Radzinsky is about as humano-chauvinist as anyone you’re ever likely to meet. I haven’t seen anything she may have published about it, but let me guess. ‘They have no complex means of communication, and therefore cannot be considered truly sapient.’ That about right?”

“I see you have indeed heard of the lady.” Portnoy nodded. “That’s almost exactly what she said. And, having said it, how do you think a graduate assistant of hers who seriously postulated that they do, indeed, have a ‘complex means of communication’ would fare in the ranks of academia?”

“I believe the appropriate term would be ‘crash and burn.’” Duncan shook his head. “If there’s a woman in the galaxy who’s more protective of her reputation, I’ve never heard of her. Another reason I’m not a fan.”

“And that’s why the assistant’s report hasn’t been officially circulated anywhere. But a copy of it floated across our horizon a few months ago, shortly after they got home from Sphinx. It was a deep dive into the Radford Center’s files looking for something else entirely, and it didn’t mean a whole lot to the team that actually stumbled across it. In fact, it didn’t mean anything to us until someone on the strategy board happened across it in a summary of the data we’d acquired.” Portnoy shrugged. “Sheer serendipity, really.”

“Sounds like it,” Duncan agreed. “And they really think it’s worth looking into as a serious possibility?”

“You know the Alignment.” Portnoy shrugged again. “We’re probably the galaxy’s biggest knowledge sponge. And I figure it probably popped a flag on one of the genome board’s search filters. They’re always looking for blue-sky possibilities that might give us an edge, and it’s not like they’re all that concerned about Beowulf finding out they’re looking at nonhuman gene donors.”

“No, I suppose not,” Duncan said thoughtfully. “But you said something about finding a pretext to send me?”

“Didn’t even have to look very hard,” Portnoy assured him. “The Star Kingdom’s asking for more help.”

“They are?” Duncan looked at him for a moment, then snorted. “Of course they are. If Richard’s right and they see even the remotest possibility of Sphinx turning into a second Barstool, they absolutely have to dot every I and cross every T, don’t they? And that’s completely on top of the legitimate interest any xenologist worth his salt would feel!”

“Exactly. And since their scientific establishment’s not exactly cutting edge—it’s not bad at all, considering their circumstances, but they’re definitely not a heart world—they’re trolling for xeno-anthropologists to help evaluate the treecats. And they’re offering some very attractive on-site incentives. Including first publication of anything really interesting that turns up. Reading between the lines, I’d say there’s a lot of interest in determining just how intelligent the treecats are and not necessarily on the part of people who wish the little beasties well. It looks to me as if the Star Kingdom’s government knows that and they’d love to have as many neutral third parties as possible involved in evaluating the treecats’ intelligence or lack thereof, if only to cover their ass when they finally rule one way or the other. The stipends they can offer aren’t very high, but they’re paying for transportation and defraying virtually all of the researchers’ on-site expenses. That’s the help-wanted ad I was talking about. We don’t want to waste the time sending letters back and forth to get them to pick up your shipfare, though, so—”

“So the way this would work,” Duncan interrupted, “is that the Foundation’s getting involved proactively because of its mandate, since this is only the twelfth tool-using and at least potentially sentient species we’ve ever encountered. Obviously we need to find out everything we can about it! And, of course, responding to Manticore’s need for assistance ties into the philanthropic side of its mandate. The University’s getting involved because the Foundation’s willing to pick up the tab for a twenty-one-T-month roundtrip voyage and essentially fund the entire effort. And I’m getting sent along because the fact that I’m the vice chair of the Xeno-Anthropology Department and the kid who discovered them is my first cousin—once removed, anyway—makes me the logical person to head the expedition. Which expedition will, hopefully, bring fresh prestige to the University. And, even if it doesn’t, the University gets brownie points for trying to help out a poorer-than-dirt star nation that’s still coping with the aftereffects of a plague that damn near wiped it out. That’s about it?”

“That’s about it,” Portnoy agreed with a nod. “Except, of course, for the bit you left out.”

“That would be the bit where anything I find out about how their telepathy actually works—assuming such a thing really exists—gets shared with the Alignment first.”

“And probably never gets shared with anyone else at all, assuming the genome board decides there’s really a possibility of modding it into the human genotype,” Portnoy said much more seriously.

“Yeah, I can see that,” Duncan acknowledged.

“And it does get you out there to visit your cousins,” Portnoy pointed out. “That’s a plus, too, I think!”

“That’s true.” Duncan nodded and smiled. “I miss Richard, dammit. And Marjorie never did get me the recipe for her Singapore Noodles.” He rubbed his chin for a moment. “Should I assume I’ll be traveling solo? Aside from whoever the University sends along, at least?”

“The intelligence directorate will probably want to send at least one of its specialists along to ride shotgun,” Portnoy said.

“Really? That’s necessary?” Duncan’s distaste was obvious, and Portnoy shrugged.

“If it turns out there’s anything to this whole theory, then the geneticists are going to want treecats, or at least their genetic material, Duncan. Frankly, what they’ll really need are live treecats, because it’s sort of difficult to demonstrate and evaluate telepathy between living brains when you don’t have a living brain to communicate with. It’s not likely anyone in the Star Kingdom will sign off on removing any live treecats from Sphinx, though. So it would seem to be a good idea to send along someone with the…expertise to arrange a treecat extraction if that seems indicated. And, like you say, it’s a ten-plus-T-month trip from Meyerdahl to Sphinx, so it makes sense to send the specialist in question on the same ship.”

“I suppose,” Duncan said.

His distaste didn’t abate, however; not that Portnoy was surprised. Like all of the Mesan Alignment’s members, Duncan Harrington was fiercely devoted to the concept of humanity’s genetic uplift. And equally fiercely opposed to the Beowulf Biosciences Code’s prohibition on anything that even hinted at genetically engineered “supermen.” Most of them would admit that prohibition had actually made sense immediately after Old Earth’s Final War and the horrors of the genetic weapons—and the genetic “super soldiers”—the belligerents had deployed. But that had been over six centuries ago, and what had made sense then was a useless, stultifying relic of the dead past. The potential for improving the basic human genome was mind-staggering. Someone like Duncan—a member of one of the Alignment’s alpha lines; Portnoy himself was only a beta line—was an example of what the Alignment’s geneticists had already accomplished: smarter, longer-lived, resistant to a host of diseases that had plagued humanity for thousands upon thousands of years, stronger and physically tougher than even the standard Meyerdahl package.…It was a long list, and the Harrington Line was scarcely the only alpha line to come out of Meyerdahl. The basic Meyerdahl genetic modifications had been a huge step in that direction, one that had been “grandfathered in” from well before the Final War, and they’d provided an ideal testbed—and concealment—for the Alignment’s further improvements.

But the galaxy at large, and especially Beowulf and the Solarian League, the arbiters of interstellar medicine, would never have allowed that sort of planned, targeted improvement. It was anathema to them, which was what had forced the Alignment underground. Forced it to conceal its purpose, conduct its mission—wage its holy war, in many ways—covertly, always in hiding.

That grated on a lot, probably the majority, of the Alignment’s members, and that had led to a…division of opinions within it. The vast majority of the Alignment was located on the planet Mesa, where concealment was fairly simple, and worked solely within Mesan family lines. A few of those lines had spread off-world from simple emigration, although those cases were vanishingly rare.

But another portion of the Alignment had very quietly dedicated itself to a far broader and more audacious goal. It might be forced to conceal its actions even from its fellows on Mesa, but its purpose was the genetic uplift of society as a whole, and it had been quietly but deliberately extending its efforts to other planets for two or three generations now. Given the galaxy-wide acceptance of the Beowulf Code it was forced to keep its activities very, very clandestine, but it was steadily expanding its reach, with more and more of its members achieving positions of influence from which to shape opinion and awareness against the day its mission could become public.

Duncan Harrington was one of those influencers, and Portnoy knew how much Duncan hated the need for secrecy. He understood it, but he didn’t like it one bit. He’d hated having to recommend against telling his own cousin, someone who’d grown up more as his younger brother than “just” a cousin, the truth, but he understood that the Alignment had to pick and choose the conservators of its mission carefully. There were seldom more than one or two fully informed members in any given line—outside the Mesa System, at least—in any generation, and sometimes, when there were no suitable candidates for the mission, it simply had to let that branch of the genome go completely, as in Richard Harrington’s case.

It was just as well that he was unaware of certain other harsh realities, however, Portnoy thought now, looking at his friend. Like the fact that if revealing their branch of the Alignment’s existence to a potential recruit turned out to be a mistake, it had to be rectified. He would have reacted poorly to that knowledge.

Yet that was okay, Portnoy reflected. Thinking about things like that was one of his jobs, not Duncan’s. On the other hand, Duncan understood the need for the Alignment to consider every possible advantage in its mission, cast the widest possible net as it considered ways in which the genome might be improved. And he understood that required research and that sometimes clandestine research had to embrace clandestine means to achieve its ends. So in the end, he’d…accommodate the necessary “specialist,” and Portnoy was glad, because he’d known Duncan Harrington since boyhood. Duncan was too good a man—too good a friend—to be burdened with those sorts of decisions, so Abner Portnoy would make certain he wasn’t.

“Hopefully, there won’t be even a ripple, Duncan,” he told his friend now. “So go. Have fun! Spend some time with Richard, hug Marjorie for me, and see what that precocious young cousin of yours has been up to. I know you’ve missed them, so make the most of it, okay? And this way, the entire trip’s on the Alignment’s tab!”

1

“This could have far-reaching consequences,” George Lebedyenko, known on social occasions as the Earl of Adair Hollow, said, tipping back in his office chair as he watched the smart wall. “From what I’ve read of the preliminary coverage, the treecats’ actions are central to the prosecution’s entire case. And so far, everything Karl’s said bears that out.”

“I agree it’s getting the ’cats plenty of coverage,” Gwendolyn Adair said. “I don’t know how much it’s going to move the needle on the question of their intelligence, though.”

“Oh, come on, Gwen!” Adair Hollow snorted. “I know the defense is doing its damnedest to downplay the ’cats’ intelligence to undercut their evidentiary value, but I think that’s going to shoot him in the foot before it’s all over. And you and I have seen the evidence from the Foundation. There’s no question that they’re a sapient, tool-using species! And you’ve seen even more of Stephanie and Lionheart than I have.”

“And I’m not the one arguing with you,” Gwendolyn pointed out just a bit acerbically. “For that matter, I’m pretty sure we both know where the…counternarrative is coming from.”

“Angelique,” Adair Hollow said in a disgusted tone.

“Not openly, and not all by herself, but almost certainly,” Gwendolyn agreed. “You’d think somebody as wealthy as dear Countess Frampton would figure she already has enough money, but she’s way too invested in those Sphinx land futures to go down without a fight. And the fact that she’s not openly campaigning against the treecats worries me.”

“I know.” Adair Hollow ran his fingers through his dark hair. “And let’s face it, she’s better at the political stuff than you and I are. That’s why she’s not ‘openly’ campaigning. Keeping her hands—and skirts—clean for Parliament and the newsies.”

“And disconnecting the nonpartisan, purely scientific debate from anything sordid, like profit,” Gwendolyn pointed out to her cousin.

“There shouldn’t be any debate,” Adair Hollow said stubbornly, returning to his original point. “From what Karl’s said, the ’cats saved both their lives this time!”

“Of course they did. But as Doctor Mulvaney pointed out last night, we have to be ‘careful’ about assigning ‘full sapience’ to them.”

The irony in Gwendolyn’s tone could have turned Jason Bay into a desert, Adair Hollow thought, and with reason. Clifford Mulvaney had an enviable reputation as a xeno-biologist, and Idoya Vásquez, the Star Kingdom’s interior minister, had imported him from Sigma Draconis as a consultant. At first, despite a certain professional caution, he’d looked like one of the treecats’ greater boosters, but he’d backtracked. To be more precise, he’d begun warning against “prematurely assuming” a greater degree of intelligence on the six-limbed arboreals’ part once their lack of any discernible language became apparent. His appearance on Alana Martínez’s “Did You Know?” podcast the night before had underscored that point yet again.

“I couldn’t believe he was comparing them to ‘service animals,’” the earl said disgustedly.

“Fair’s fair, George,” Gwendolyn replied. “He didn’t actually compare them to service animals. He simply said that to date, aside from the very simple tools and artifacts we’ve seen out of them, they haven’t really done anything in relation to humans that service animals haven’t also done for millennia. And in a lot of ways, he has a point. For that matter, some of the arguments we’ve been putting forward in favor of treecats in public places are being construed that way, and you know it.”

“But service animals do things because they’ve been trained to,” Adair Hollow shot back. “They don’t do them spontaneously, without ever having been taught to.”

“I agree.” Gwendolyn nodded. “And it was at best a poorly chosen analogy, since it can be interpreted as suggesting the treecats are no more intelligent than, say, a German Shepherd! But—”

“Hold that thought.” Adair Hollow raised one hand. “We’re back.”

Gwendolyn’s green eyes moved back to the smart wall as the holding pattern disappeared to show them the courtroom once again.

“Ms. Harrington,” Stephen Ford began, “or would you prefer to be addressed as ‘Probationary Ranger’ Harrington?”

Ford, the defense attorney for Erina “Stormy” Wether, looked precisely like central casting’s version of the “promising young attorney”: well-groomed, not flashy, but somehow completely fake. He spoke to the sixteen-year-old in the tone of voice some adults reserved when they were pretending to treat people they still thought of as “kids” as adults. Stephanie Harrington hoped this was just because she was short for her age. She knew her fine-boned build made her look younger.

She squared her shoulders, but kept her hands neatly folded in her lap, so she wouldn’t give into the temptation to play with her hair. Over the last year, she’d been working on growing it out. Today her mom had helped her pull the curly brown locks back into a neat little ponytail that tickled her neck. It also reminded Stephanie acutely of the treecat who wasn’t there, but instead waited in the chamber reserved for pets.

“Ms. Harrington is fine,” Stephanie said. She was actually very proud of her rank, especially since the position had been created specifically for her, but the way Ford said it, “probationary ranger” sounded more as if she’d done something wrong and was “on probation,” rather than what the term actually meant, which was that in defiance of a policy against interns, and especially junior interns, Stephanie was officially enrolled as the most junior member of the Sphinx Forest Service.

“Ms. Harrington,” Ford continued with a meaningless smile, “you were present in court for the testimony of Ranger Karl Zivonik of the Sphinx Forest Service. Would you confirm whether you agree with the accuracy of his testimony regarding how the two of you came to be in the area where Gill Votano was concealing evidence of valuable mineral resources?”

Stephanie hated how Ford’s wording made Gill sound like the criminal, rather than the victim. Nevertheless, she kept her voice level as she replied. “Yes, I do agree.”

“Very well. Rather than go over those details, I’d like to move to the point where your specific actions have a marked impact on the evidence against my client.”

Ford paused for dramatic effect, drawing his right index finger over his right eyebrow with what, based on how many times Stephanie had seen him do it, was clearly his trademark gesture. Stephanie waited for him to continue with a patience she didn’t feel. She wanted her part in this trial to be over, to go back to sitting on the bench next to Karl. Even better, she’d like to collect Lionheart from where he’d been exiled with Survivor in an area reserved for “pets”—if he’d been classed as a “service animal” he’d have been allowed to accompany her, but of course he hadn’t been granted that status—then leave this stuffy courtroom behind for good.

“After learning of the apparent suicide of Gill Votano,” Ford continued, “you and Karl Zivonik decided to take an air car ride out in the direction you thought Votano had intended to bring you for a tour that very day. You were upset?”

“Some,” Stephanie said honestly. “We didn’t know Gill very well, but we did like him, and he’d seemed very enthusiastic about our planned outing. It didn’t seem to fit that he’d killed himself, but apparently, he had.”

In the months since Gill’s death, Stephanie and Karl had worked hard on how to present why they had been in the right place to get the evidence that proved Gill had been murdered while keeping the role Lionheart and Survivor had played in the investigation out of the picture. It wasn’t easy since, from the start, Lionheart and Survivor had been deeply involved.

The treecats’ sensitivity to emotional landscapes had alerted Stephanie and Karl that there was more to Gill’s invitation than the geology field tour he’d ostensibly offered. The treecats also had been the ones who had noticed—likely because they picked up Gill’s scent—the concealed crevice which contained the evidence as to why someone might want Gill dead. And it had been the treecats who had alerted their humans to the presence of someone else in the area, which had definitely been crucial to the case’s resolution. Finally, the treecats had saved Karl and Stephanie’s lives, without which action, there would be no trial today.

“So, you decided on a memorial outing,” Ford prompted. “Very touching. Ranger Zivonik has already related how you two came to the place where you noticed a slab of rock where it shouldn’t be, and how you decided to move it, thereby finding a concealed crevice. Very impressive.”

Stephanie inclined her head slightly, as if acknowledging praise, though she suspected the opposite was intended. When he’d been on the witness stand, Karl had done a magnificent job explaining how the pair had spent a lot of time outdoors, not only in their work, but in hobby activities like hunting. This meant that even in an unfamiliar environment they were inclined to notice what didn’t fit. Stephen Ford had been reprimanded by the bench for grandstanding when he’d tried to discredit their testimony by stressing the unlikelihood that their skills would have translated from Sphinx’s forests to Gryphon’s rocky wastes. After all, how or why they’d ended up in the right place wasn’t germane to the case at hand.

“I must say, Sphinx certainly is a challenging environment,” Ford continued. “Not only are even you young rangers so keen of eye that you can spot a stone out of place, but you can apparently scent a nearly odorless gas before it knocks you out. Ranger Zivonik has admitted he did not hear or smell the gas. However, Ms. Harrington, you did so with sufficient time to switch your uni-link to record both audio and visual images. Please tell us in your own words what happened.”

Stephanie was ready for this question.

“We’d gone back into the crevice and seen the mineral formations. We made some images, and were walking back when, I’m not really sure…I heard something, or maybe Lionheart started acting edgy.”

“Lionheart?” Ford cut in. “That’s your pet treecat, correct?”

Stephanie fought an urge to roll her eyes. “Yes. Lionheart is a treecat.”

“And so when your treekitty got nervous, you—”

“Treecat,” Stephanie corrected icily. “Cattus arbor habitans if you prefer. That’s the currently agreed upon nomenclature.”

Ford gave a showman’s laugh. “Oh, I don’t prefer it, really. Quite a mouthful for such little beasts. Please go on.”

Although Stephanie wanted to snap at him, she suddenly realized that the defense attorney wasn’t being nearly as stupid as he seemed. Although it was unlikely Stormy would get off on the charge of first-degree murder, she had been careful about covering her tracks. This had given the defense the opportunity to portray her as a pathetic and frail old woman who had perhaps been incapable of judging her own actions. Stormy herself had been playing the role to the full, sitting slumped in one corner rarely reacting to anything said. If she did react, she did so inappropriately, seeming to care more about having her teacup full than that she was on trial for her life.

If any of those testifying against Stormy could be made to seem unreliable—especially Jorge Prakel, whose testimony was key to proving that Stormy’s actions were premeditated—the defense might be able to get the charge reduced, or even dismissed. If that happened, then the case against Stormy Wether would move to the secondary charges, which included the attempted murder of Stephanie and Karl. Since they’d only escaped death by poisonous insect sting because of the intervention of Lionheart and Survivor, anything that could make what had happened on that stony outcrop in Gryphon’s outback seem open to different interpretations would be gravy from the defense’s point of view.

So, I need to respond without making the treecats seem dumb or, worse, letting on how smart they are. Okay…time to do a little offensive myself.

Stephanie narrowed her large brown eyes in her best serious and intent expression, then asked, “Why Karl and I were there doesn’t really matter, does it? What matters is that I turned on my uni-link to record both audio and visual. The images aren’t the best, but they’re good enough to show that when Karl and I went down after being gassed, the person who picked us up, moved us, then set us up to—”

Stephen Ford held up one hand.

“What the images apparently show is not germane to my question. Thank you, Ms. Harrington, that will be enough.”

He glanced at his notes, apparently decided against the wisdom of keeping Stephanie on the stand any longer than necessary, and asked her to step down. She did so, restraining an urge to hurry to where Karl Zivonik sat, tall, dark, and reassuring. Instead, she held her head high and walked with a measured tread to her seat.

In the lull before Ford called his next witness there was the usual murmur from the press gallery as they speculated on the significance of each stage of the trial. As Stephanie took her seat, she glanced up to see if she could judge what impact her own small contribution might have had. To her surprise and delight, she recognized a familiar face, large-nosed and unmistakable: José “Nosey” Jones, the owner of and sole reporter for the popular Sphinx Oracle.

She nudged Karl and said in a soft voice, “Nosey’s here!”

Karl grinned, his gray eyes sparkling. “Wondered when you’d notice. He’s been up there all day.”

A short while later when a recess was called for lunch, Stephanie looked up into the press gallery and gave Nosey a little finger wave. Nosey beamed and pointed to his uni-link. A moment later, a message came up on both her screen and Karl’s.

“How about lunch? I’d love a chance to catch up,” Nosey suggested. “You’ve been gone nearly eight months. Messages just aren’t the same.”

“That would be great,” Stephanie replied. “I really want to get away from the courthouse.”

“Me, too,” Karl added. “I realize the defense has to show willing, but this morning was absolutely no fun.”

“Then meet me outside the west exit?” Nosey suggested. “I’m staying at the Blue Basil, which is in easy walking distance. I’ll com an order for food in advance. If we take the side entrance into the hotel, then the treecats shouldn’t attract too much attention.”

“Great!” Stephanie texted back.

After collecting Lionheart and Survivor, Stephanie and Karl met up with Nosey. Nosey’s long, lanky build testified to his birth off-Sphinx, but here on Manticore, he could do without a counter-grav unit. His pale blue eyes were thoughtful and sensitive, and nicely contrasted with his reddish-brown complexion. He was somewhat older than Karl, in his twenties. Initially, Nosey and especially his articles in his Sphinx Oracle, had more irritated Stephanie than otherwise, but she’d come to appreciate that he cared about Sphinx as much as she did.

“What brings you here?” Karl said, shaking hands with the other man.

“Why do you think I’m here?” Nosey’s lips curved in an impish smile. “I’m here to provide firsthand coverage of the testimony of Sphinx’s own heroic rangers. Trust the two of you to get into trouble, even on holiday on another planet!”

“I wish we hadn’t,” Stephanie said. “I don’t mean I regret stepping in, but it would have been a lot more fun to explore a new planet without having a murder investigation mixed in.”

“I get you,” Nosey said, giving Stephanie a friendly pat on the shoulder that was in no way condescending. “But you two aren’t the type to let something go just because you’re not on duty. We’re all proud of you back home. That’s one of the reasons I decided to make the trip and provide an on-the-scene report. Another reason is that I am solidly sick of snow and ice. C’mon, we can walk to the hotel from here. It’s great to be out of doors.”

As he led the way toward his hotel, Nosey continued chattering.

“Back home, people can follow coverage of the murder trial in the Manticoran press, sure, but they’re not going to know the background of the people involved. Stephen Ford, the attorney for the defense, is a great example. He wants to go into politics in a big way. Rumor is, that’s why he took this case, even though Ms. Wether isn’t likely to get off. Even if Ford fails completely, he’s already gotten lots of publicity, as well as support for his claim that he’s all for the underdog. Voters love that sort of thing. If Ford gets the charges against Wether reduced, that will work out even better for him.”

“Yeah, we heard a few rumors about Ford’s ambition,” Karl said.

Stephanie nodded agreement, but was too distracted to comment. As Nosey talked, she was picking up some curious vibes. Underlying Nosey’s genuine enthusiasm for his topic was a sense of mingled apprehension and excitement. Stephanie had found, since her adoption by Lionheart, that what her mom called her “people sense” had improved markedly. She suspected most of that was simply the fact that she was almost six T-years older and that she’d become much more comfortable with people in general. There were times when she suspected it might be more than that, though. She’d become certain the treecats were empaths—that they could literally feel another’s emotions—and sometimes she suspected that might be leaking over to her. Yet every time she tried to narrow it down, all she got was a frustrating mental tickle she couldn’t be at all certain wasn’t simply her own imagination. One thing she did know, though, was that she’d learned to use Lionheart as an emotional barometer as she’d become more and more adept at reading his body language. At the moment, as he rode in his accustomed place, his rearmost set of feet resting on a reinforced panel in her tunic, his mid-limb hand-feet on her shoulder, his head was cocked with an almost speculative air as he gazed at Nosey.

Nosey’s hiding something, Stephanie decided, but Lionheart doesn’t seem worried. If anything, he seems amused! I wonder if there’ll be celery for lunch or something.

She glanced over at Karl and could tell he also suspected Nosey planned to surprise them with something based on Survivor’s reaction. Over the last year, they’d had plenty of opportunities to compare how well they could “read” their treecats. Stephanie was definitely better at it, although whether that was because she’d known Lionheart longer and had more practice, or for some other reason, they really didn’t have enough information to figure out.

There’s still so much we don’t know about treecat and human interactions, Stephanie thought. But, as the pool of adoptees grows, we’re getting more and more information. Eventually, we can stop generalizing from too small a sample set.

When they reached the Blue Basil, the three Sphinxians slipped in a side door, then took the stairs to the third floor. Once there, Nosey palm-coded open the door to his hotel room, and sniffed the air with ostentatious satisfaction. “The food beat us here. I remembered you both liked pizza, so I ordered several combinations, as well as salad, and dessert. I ordered sushi for the treecats, but extra for the humans, if the ’cats decide to share.”

This little bit of business had taken them into the hotel suite proper. The food was indeed waiting, spread out temptingly on a long, low table in front of a comfortable-looking sofa. Presiding over the banquet, managing to look both smug and shy at the same time, was none other than Trudy Franchitti. Trudy got to her feet as they came in, a welcoming smile brightening her undeniably lovely face.

Not too many years ago, if Stephanie had been asked to name her least favorite human on Sphinx, Trudy Franchitti would have likely topped the list. Not quite a year older than Stephanie, Trudy had been her rival on the Twin Forks hang gliding team—that is until she’d dropped out at the prompting of her then-beau, Stan Chang. But Trudy had changed a lot in the last year. She still had the curves that had made Stephanie feel like an underdeveloped kid, the big violet-blue eyes, and the shining dark hair, but Trudy no longer went out of her way to hide her intelligence and how deeply she cared about the well-being of Sphinx’s wildlife.

Trudy had always been interested in the wild creatures of Sphinx. In fact, her numerous wild-captured “pets” had been one of the sources of contention between her and Stephanie. However, when the recent severe fire season had put those pets at risk, Trudy had actually stood up to her domineering father, and insisted on getting them treated at Richard Harrington’s vet clinic. Soon after, she’d started volunteering with Wild and Free, an animal rescue and rehabilitation group. By the time Stephanie had left for Gryphon, she’d actually been starting to like Trudy. Still, that didn’t mean she wasn’t shocked to find Trudy sitting here in Nosey’s hotel room, or that the slightly open closet door showed what had to be one of Trudy’s outfits hanging in the closet.

With the air of one making a wordless declaration, Nosey went over to Trudy and gave her a kiss, right on the lips. Then he motioned to the two chairs set to one side of the coffee table.

“We’ll sit on the sofa. You two take the chairs.”

Trudy indicated the space between the chairs. “I spread a couple of towels there so Lionheart and Survivor could be as messy as they need to be. I hope you don’t mind, but when we ordered lunch, I did ask for a few sticks of celery, along with the salads.”

Stephanie managed to swallow all the questions burbling up in her throat and say, “No, I don’t mind. Very kind of you to think of them.”

Karl, normally the less outspoken member of their team, helped himself to a slice of pizza with mushrooms and sausage, then asked the burning question, “So…How long have you two been dating?”

Trudy actually blushed, which surprised Stephanie, since it had been a pretty open secret that Trudy and Stan had long gotten past holding hands.

But then, romance and sex aren’t the same thing, are they? Even if they get mixed up together all the time.

Nosey grinned happily and reached to squeeze Trudy’s hand with the hand that wasn’t holding a slice of pepperoni and pink olive pizza.

“A few months now. I mean, since we decided to date just each other. We started spending time together further back, when I wanted to do a feature story on Wild and Free for my Nose for News column in the Oracle. I’d met Trudy at your sixteenth birthday party, Stephanie, and we’d chatted there, so she offered to be my guide around the facility. We got to talking and—”

“And it was just so easy to talk to him,” Trudy cut in, giving Nosey a melting look. “At first, we mostly talked about animals, and the impact of fires on habitats, and stuff like that, but I was still really messed up over Stan’s death. For a while after Stan died, I tried not to think about what had happened, concentrated on my PT, all that. But there was too much to just keep stomping down, not just the sorrow—we’d dated for a long time, and Stan hadn’t always been such a jerk—but the anger, too. He’d put us at risk, and…Oh! It’s stupid, but I couldn’t help but feel like Stan had gotten off easy. If it hadn’t been for Karl showing up right after the accident, I might have been dead, too. I had a lot of pain, especially during rehab. But thanks to some great doctors, all my scars were inside. Even after my body was mostly healed, and I was supposed to be ‘all better,’ those emotional scars were still there. Not just still there, worse than ever.”

“I understood some of what she was feeling,” Nosey continued, motioning for Trudy to take a bite of her pizza. “I mean, I’d had my own experience healing from bad injuries not that long before. My injuries were also connected with fear and resentment, and…” He gave an eloquent shrug. “We talked a lot about how we felt. One thing led to another, and, well, here we are!”

“That’s terrific,” Stephanie said and meant it. “I’m really glad for both of you. I guess your families must be pretty pleased, too.”

Nosey laughed. “My sister is thrilled. She loves Trudy to bits. My mother can hardly believe I have a serious girlfriend. She’d decided I was married to my job.”

Trudy laughed with him. “His family is great. I was so nervous when I met his sister—she’s the only one of his sibs who lives in the Star Kingdom—but…”

The long, involved anecdote that followed was backdropped by the demolition of several pizzas, large salads, then slices of a rich, multi-layered cream cake. Stephanie out-ate everyone else, but not even Karl teased her. It was only after the talk had turned to the trial, which Trudy had been watching on the vid, since she couldn’t sit with Nosey in the press box, that Stephanie realized Trudy had neatly dodged how the Franchittis felt about their daughter’s new boyfriend.

Didn’t Nosey call out Jordan Franchitti in at least one of his columns? Something about how the Franchittis weren’t helping one of their tenants whose home had been seriously damaged during the fires? Stephanie thought. But they must not mind the relationship. I mean, Trudy’s here, with Nosey, staying in his room.

But thinking about what Trudy hadn’t said, she definitely wondered.

<I am surprised,> Climbs Quickly said around a glow of amusement. <I would not have expected Needs to Know and Walks in Shadow to mate.>

<Nor would I,> Keen Eyes replied with an answering flicker of laughter.

The two People lay stretched comfortably along the backs of their two-legs’ sitting things, nibbling the pieces of spicy, bright-tasting food their bondmates offered them from time to time.

<Still,> Keen Eyes continued more soberly, <I think this may be very good for both of them.>

<I think it has already been good for both of them,> Climbs Quickly agreed. <His heart is far lighter than the last time I tasted him. And the shadows through which she walks seem lighter, somehow, when she is with him.>

Keen Eyes radiated agreement, and Climbs Quickly thought back to his first meeting with Walks in Shadow and how much the young female two-leg had changed since then. Once again, he wished Death Fang’s Bane were able to taste other two-legs’ mind-glows, because all she had felt where Walks in Shadow was concerned in those early days of their bond had been frustration and anger. Climbs Quickly still had no idea what had shadowed the other two-leg’s life, but he knew the pain of it had shaped Walks in Shadow’s life as the cold, powerful winds of the high peaks twisted and blighted the trees that grew there. And the things that had so angered Death Fang’s Bane had grown out of that pain, out of the defenses Walks in Shadow erected about it.

And they are too mind-blind to recognize even that much about one another, he thought pityingly, for far from the first time.

<And yet is that not a part of their courage?> Keen Eyes asked, following his thought. <The courage to continue, day after day, and to reach out to one another despite their mind-blindness? I do not think one of the People could do that.>

<That is a very good observation,> Climbs Quickly said approvingly. <And I hope Walks in Shadow’s courage will carry her still farther from the shadows. There was a time when I would not have believed she and Death Fang’s Bane could ever become true friends, yet they have. And now, with Needs to Know, I think perhaps she is ready to take yet another step.>

2

“Stephanie! Karl!”

Stephanie looked up when the deep voice called her name, then smiled as Oswald Morrow crossed the Sweet Onion’s lobby toward them. Her smile was a bit restrained, although it wasn’t because of anything Morrow had ever done. In fact, he was one of the most helpful and open-minded people she’d ever met where the treecats were concerned. But something about him put Lionheart ever so slightly on edge. Whatever it was, it clearly hadn’t set off her companion’s “Danger!” alert, but the trace of wariness—that was the only word she could think of—she sensed from Lionheart whenever Oswald was around bothered her. At the same time, she reminded herself conscientiously, despite her enormous faith in the treecat’s judgment, Lionheart was a treecat, whose understanding of humanity was probably at least as incomplete as humanity’s understanding of his species.

Well, maybe not that incomplete, she thought dryly as Oswald reached her, Karl, and her parents.

“Richard, Marjorie.” He held out his hand, shaking each of the elder Harringtons’ hands in turn, and then shook his head at the younger members of the party.

“I’ve been watching you on HD,” he said. “Sounds like your furry friends came through for you two again.”

He smiled at Lionheart and Survivor, riding on Stephanie’s and Karl’s shoulders. The Sweet Onion had become one of the Harringtons’ favorite dining spots, and not just because of how good its Old Earth Italian cuisine was. Salvatori Jackson, the owner, had made both treecats welcome, and highchairs were already waiting at what had become the Harringtons’ usual table.

“Will you join us?” her father asked.

“No, sorry. Joan and I are dining with friends, and I’m waiting for the rest of them to arrive. But am I going to see you guys at the Foundation next week?”

“We’re planning on it,” Stephanie replied. “The Earl’s invited us to address the members after the trial finally ends.”

“I know he’s really front and center on looking out for the ’cats,” Morrow said in a more serious tone. “For that matter, the entire Foundation’s backing them. There’s still so much uncertainty about them, though.”

“Tell me about it!” Stephanie rolled her eyes.

The Adair Foundation was dedicated to the preservation of the Star Kingdom’s native environment, which was always a ticklish proposition when humanity turned up and started changing things. Part of that was both inevitable and deliberate. Humanity had to make some changes to make an alien planet its home, and at least over the centuries, Homo sapiens had learned a lot about how to terraform planets with minimum damage to those planets’ existing ecosystems. Unfortunately, they’d learned a lot of that by making mistakes on other planets, and some of those mistakes had been spectacular. And some, like what had happened to the Amphors, had also been not simply deliberate but among the human race’s most shameful acts, in Stephanie’s opinion.

She would have been happier if she’d been able to believe that sort of action was behind her species now, but humans were still humans and probably always would be, as the current murder trial illustrated. That was the main reason she and her friends were so protective of the treecats. But even the best-intentioned human populations could unintentionally wreak havoc on the environments of the planets they’d colonized, and that was what the Adair Foundation was dedicated to preventing.

Stephanie approved of the Foundation. Highly.

“Well, you should have pretty good attendance,” Morrow said. “It’s the quarterly meeting of the Board, after all.”

“We’re all looking forward to it,” Richard said. “I could wish we hadn’t been brought to Landing by a murder trial, of course.”

“I know.” Morrow nodded sympathetically. “But from everything I’ve heard, your young people did us all proud again. Although”—he transferred his attention back to Stephanie and Karl and shook an admonishing finger—“I wish you two could manage to live just slightly less traumatic lives for, oh, a few T-months or so.”

“We’re working on it—honest!” Stephanie said with a grin.

“Well, work harder!” Morrow laughed, then looked across the lobby. “And there’s Joan! Maybe we’ll run into each other at the Foundation.”

He waved and headed off to meet his wife, and Stephanie smiled after him for a moment before she and Karl followed her parents into the side dining room.

“I ran into the Harringtons in the Sweet Onion last night,” Morrow said, and grimaced. “Yet another eating establishment letting the little beasties in.”

“That’s partly George’s doing,” Gwendolyn Adair replied, then shook her head. “Most of them are already legally required to allow service animals. Unfortunately, young Stephanie’s been visible enough to make the leap from that to treecats a relatively short one for most people. And that may actually not be a bad thing, you know. George has had the Foundation leaning on the Restaurant and Hoteliers Association to let them in ever since Karl and Stephanie were at the University, and he has enough influence he’d have gotten them in anyway, one way or another. At least this way they’re still in the category of service animals. Which, by the way, pisses him off. But it’s going to spread, especially on Sphinx, whatever we do, so there’s no point trying to stop it now.”

“Wonderful.” Morrow sipped moodily at his drink, then crossed to the ninetieth-floor window and stood gazing down on the streets of Landing. “Countess Frampton’s not happy about this steady erosion of her position, you know.”

“Of course I know,” Gwendolyn said with a snappishness she wouldn’t have let her noble cousin see. “But like I just said”—she gave him a pointed glance—“there’s not a lot we can do about that, and at least we’ve got Mulvaney on board to help push the ‘really smart animals’ narrative. That was a good catch on your part, by the way.”

Morrow nodded with a slight smile. It was his research that had unearthed the fact that one reason Clifford Mulvaney had accepted the invitation to the Star Kingdom was the spate of bad investments which had ruined him financially back home. He’d come primarily to get away from his creditors, without ever expecting he might find a way to actually help deal with them…until Gwendolyn and Countess Frampton suggested the possibility ever so subtly and through properly deniable intermediaries. He might not have liked the idea of selling his enviable reputation to bolster the anti-treecat effort, but he’d been more than desperate enough to do it anyway.

“I’m afraid that even with Mulvaney we’re fighting a losing battle on that front, too, though,” Gwendolyn continued sourly. “If Stephanie was just a bit less effective as their spokeswoman, it would help a lot. But the damned girl’s ‘cute as a button’—that’s dear Cousin George’s revolting simile, by the way—and smarter than she has any right to be. And then there’s the damned treecats themselves.” She sipped from her own glass. “Just between you and me, I’m coming to the conclusion that they really are empaths.”

“You are?” Morrow looked over his shoulder at her with a quick frown. “I don’t like the sound of that. And I thought you’d decided they weren’t?”

“What I said—and what Mulvaney said—was that there wasn’t any proof they are, and there still isn’t. Proof, I mean.” Gwendolyn scowled. “I’ve watched Lionheart’s body language, though, both in person and in recorded video, and it’s different when I’m around. I think he’s picking up on something.”

“Like what, specifically?”

“Presumably the fact that I’m not really a great admirer of his species,” Gwendolyn said in a poison-dry tone. “It’s fairly easy to fool George and the other directors—aside from Jefferson, of course—and I’m confident sweet little Stephanie and Karl haven’t figured out we’re actually working for the other side. But the furry little troublemaker’s obviously twigged to something none of the others can see.”

“Well, that’s unfortunate.” Morrow shook his head.

“Maybe,” Gwendolyn replied. “But I think it’s also proof that however sensitive they may be to emotions, they can’t read actual thoughts. For that matter, it’s probably another indication that any kind of meaningful communication between humans and treecats isn’t right around the corner.” Morrow cocked an eyebrow, and she shrugged. “If he could actually read my thoughts—and understand them—he’d be a lot more than just…edgy around me. And if he were able to communicate clearly to Stephanie, she’d be more skittish around me, too. Assuming she didn’t just shoot me.”

“That’s something,” he conceded.

“But we can’t count on Stephanie’s not beginning to wonder just what it is about me—and probably you, Ozzie—that Lionheart’s apparently picking up. She trusts him, trusts his judgment. If I had to guess, I’d say she’s putting it down to the fact that they only ever interact with us directly here on Manticore, in the ‘big city,’ outside his comfort zone back on Sphinx. But eventually, she’ll get past that.”

“And then?”

“She’s still technically a minor, so usually I wouldn’t be that worried. But she’s got too many friends in too many places, and she’s too damned smart.” Gwendolyn shook her head. “We need to move on this, Ozzie.”

“How?” Morrow asked, his tone a bit wary, and she grimaced.

“George is still wavering, but I think he’s inclined to support Hidalgo. I’m getting behind that and pushing as discreetly as I can, because that’s probably the best position we’ll have if the rest of it goes south on us. Angelique won’t like it, but with a little political finesse, we could steer the reservations away from the areas her options cover.”

Morrow nodded. Doctor Gary Hidalgo, one of the xeno-anthropologists who’d followed the Whitaker expedition to study the treecats, had come down strongly in favor of their sapience. He’d been unwilling to offer any guesstimates about where the ’cats placed on the sentience scale, although he’d acknowledged that their lack of any spoken form of communication argued for the lower third of the scale. He’d also pointed out, however, that despite that they clearly had significant social organization and were both competent and innovative in the use of their Paleolithic tools. He’d said as much in his report to the Interior Ministry, and also argued that the Star Kingdom had a moral responsibility to minimize the cultural contamination the treecats had already suffered and prevent any future contamination, which suggested setting aside reservations for them where they could continue their development without human intervention.

Cleonora Radzinsky, on the other hand, had strongly disputed Hidalgo’s conclusions about treecat intelligence. She pointed out that even Old Earth dolphins, who rated only a point-six-five on the sentience scale, used complex verbal communication, which treecats manifestly did not. Russell Darrolyn had supported her strongly, which had been even more telling. Although Radzinsky was regarded as one of the human-settled galaxy’s foremost specialists in non-human intelligence, Darrolyn’s specialization was communication studies.

“I’d prefer Radzinsky’s and Darrolyn’s interpretation, if we can’t just have them classified as animals and be done with it,” Gwendolyn continued. “At best, though, we’re probably going to find Stephanie and her friends pushing for protected species status for them. And if that happens, it’s only a short step from that point to having Hidalgo’s reservations as our best fallback. It’s not a good one, but if we get to that point, it may be the only one we have. That’s one reason I’ve been positioning Mulvaney to support it if and when the time comes.”

“The Countess really won’t like that,” Morrow said. “She already doesn’t want anything that supports the notion that they’re a truly intelligent species at all. I think she’s afraid any step in that direction—any official, legal step, at least—will open a door that can only swing wider as time passes. And unless I miss my guess, she’ll see the notion of ‘reservations’ as exactly that: a concession to their intelligence. And that could be a bad thing for all of us.”

Gwendolyn looked a question at him, and he shrugged.

“Look, I know I’m the cutout between you and her for most of this, and I’m generally okay with that. The farther apart—officially—we can keep you and her, the less likely your cousin is to figure out what’s going on, and that’s what they call a Good Thing. But it also means I’m the one more directly exposed to her unhappiness, and I can tell you that if she gets sufficiently unhappy, moderation’s likely to go out the window. She won’t care where the chips go as long as the tree gets cut down.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning that if she decides we can’t get the job done she’s likely to get more directly involved herself. And outside political cajolery, she doesn’t do subtle very well. If she starts flailing around, looking for somebody more ‘effective’ than you and me, she’s likely to stub a toe, possibly in spectacular fashion.”

“Spectacular enough to splash on us, you mean?”

“It could happen.” Morrow nodded, his expression unhappy, and Gwendolyn’s frown deepened.

So far, aside from the muggers she’d hired to attack Stephanie and Lionheart on their first visit to Manticore—which, she admitted, had not turned out to be one of her better ideas—nothing she’d done about the treecats was technically illegal, and she was confident her links to the muggers were deeply enough buried no one would ever find them. But if an official investigatory eye were to be focused upon her, an embarrassing number of her other activities—the sort that carried prison sentences—might intrude into the light. Which didn’t even consider the impact it would have on her lucrative position as Cousin George’s right hand woman. For that matter, a forensic audit of the Foundation could have unhappy consequences.

“What was that word you used earlier?” she asked. “‘Unfortunate,’ I think you said. Just how close do you think she might be to getting more…proactive?”

“For now, she’s willing to go on playing the long game,” Morrow said. “It’s not like she ever really expected anything else. But I think she senses the way the wind is setting, and if she decides the long game is also the losing game, all bets are off. I just don’t know where that point’s likely to come.”

“So what we really need is a way to convince her that it’s not—not a losing strategy, I mean.”

“Excuse me, but isn’t that what we’ve been trying to do all along?” he observed a bit acidly.

“Of course it is. But so far, we’ve been looking at ways to, um, mitigate the problem, let’s say. How to deal with the consequences of the treecats’ existence.”

“‘Consequences,’” Morrow repeated slowly, and she nodded.

“Maybe we should consider something that looks beyond that. Sort of a Muriel Ubel sort of solution.”

Something cold seemed to settle briefly in Oswald Morrow’s stomach, but Gwendolyn only smiled at him, and her green eyes were bright.

“That might be—probably is—worth considering for some point in the future,” he said after a moment. “It’s not exactly something I’ve spent a lot of thought on, though. Or anything I think we want to be rushing into, for that matter.”

“Oh, trust me—I’m not going anywhere near a final solution to the treecat problem unless I’m confident it’ll work and that no one could trace it back to you or me,” she assured him. “But it’s definitely something we need to be thinking about, Ozzie. If it turns out we need it, we don’t want to be trying to put the pieces together on the fly. That’s how mistakes get made.”

“So for now we stick with the existing strategies?”

“Such as they are,” Gwendolyn agreed a bit sourly. Then she brightened. “Speaking of which, I have a meeting tomorrow that may give us a little more leverage, at least where the reservation strategy is involved.”

“Mr. Jones! Thank you for accepting my invitation,” Gwendolyn said, standing to offer her hand as her assistant ushered her long, lanky—and generally unprepossessing—guest into her office.

“How could I resist?” Nosey replied with a broad smile, and Gwendolyn revised her initial impression upward. It was a most engaging and infectious smile, the sort that was undoubtedly useful to someone with journalistic pretensions.

“Oh?” She cocked an eyebrow at him, and he shrugged.

“I’ve been a fan of the Adair Foundation for a long time, Ms. Adair. And my friends Stephanie and Karl have told me how helpful you’ve been to them. Even putting all of that aside, though, it’s my opinion that the story of the treecats can only grow going forward, especially back home on Sphinx. So anything the assistant director of the Adair Foundation—the most influential environmental preservation organization in the entire Star Kingdom—might have to say on the subject is obviously worth hearing.”

“Really?” Gwendolyn waved him into a chair and seated herself behind her desk once more. “That’s a very flattering description of the Foundation, but we’re scarcely alone in our concern for the environment. There’s the Donaldson Group, and Stephen Atkinson’s organization. And, truth to tell, Interior Minister Vasquez is fully on board.”

“I know.” Nosey nodded and settled into the indicated armchair. “There’s more than one voice speaking up, but Adair is the most influential—and best funded—of the lot.”

“That’s probably true,” Gwendolyn acknowledged gravely, leaning back in her own chair. “Still, it’s not as if anyone in an official position is about to sign off on any ‘slash and burn’ approaches to exploiting Manticore or Sphinx. Or even Gryphon! To be honest, that’s not really what we’re concerned about.”

“You’re concerned about private enterprise,” he said, and it was her turn to nod.

“Exactly!” she replied, putting approval for his ability to see where she was headed into her tone. “That horrible business you were involved in with Lyric Orgeson was bad enough, but then there was Muriel Ubel.” She shuddered.

“You’re right, Orgeson was pretty bad.” Nosey grimaced. “I guess I’d feel that way about anybody who had me beaten up and threatened to have me killed, but I was hardly the only person she was ready to hurt. On the other hand, she was mainly interested in stealing the recipe for baka bakari.” He grimaced again. “Somehow, I doubt a drug cartel’s likely to do as much damage as Ubel did!”

“No, it’s not. But it does rather tie into what most concerns the Foundation as a future threat not just to the treecats, but to any number of other species of flora and fauna that we don’t know anything more about—yet—than we knew about treecats before Stephanie encountered Lionheart the first time or about the possibility of baka bakari before Glynis Bonaventure started researching Sphinx’s fungi. There’s no way of telling what sort of other possibilities we’re going to discover, and I’m less concerned—the Foundation is less concerned—about what official agencies might do than we are about private citizens and private entities who recognize those possibilities when they arise. Not all of our citizens are as mindful of the wilderness as Stephanie and her parents—or you, judging from your articles, especially about the treecats. What Ubel did after her research went south and got loose was probably worse than the vast majority of other citizens of the Star Kingdom are likely to do. Very few of them would commit mass murder to cover up their mistakes or even their deliberate destruction of habitat! On the other hand, how many of them would have as much to lose as she did if anyone found out about what they’d done? Don’t fool yourself. There are plenty of people out there who are willing to exploit our planets however destructively they have to to accomplish whatever goals they may have.”

“I suppose that’s true,” Nosey said. “No, I know it’s true. If Orgeson had been able to produce the baka bakari she wanted by clearcutting entire hectares of Sphinx, she would’ve done it. And she wouldn’t have cared what she had to do to protect herself if anyone found out and objected to it.”

“Precisely.” Gwendolyn let her chair come upright. “That’s why the Foundation’s pursuing a multipronged policy. We’re very active in public education, which is one reason we’ll be providing private funding for the Forestry Service’s Explorers and other leadership programs, and that’s only one of the educational initiatives we’re backing. At the same time, our staff is in consultation with Ms. Vasquez and her analysts at Interior, as well as private analysts and environmentalists, to develop public policy as proactively as we can. We’d really prefer to have solutions we can offer even before the Star Kingdom at large becomes aware there’s a problem that needs solving.”

“That makes a lot of sense,” Nosey agreed.

“We’re looking at quite a lot of potential, long-term issues,” she told him. “For example, very few people are aware that it looks as if the hexapuma population is in significant decline.”

“Really?” Nosey blinked in surprise.

“It’s still hypothetical at the moment, but the research and the number of sightings both suggest that populations are shrinking. Some of that’s inevitable, given their territoriality and how large their ranges are. There are seldom as many apex predators as the general public assumes there must be, and something the size of a hexapuma needs a lot of prey animals. Which means that too often human homesteading and other activities encroach on their ranges. And, unfortunately for hexapumas, their territorial nature produces extraordinarily aggressive and dangerous behavior when that happens. That, in turn, results in a steady trickle of dead hexapumas killed in legitimate self-defense, which doesn’t even consider the number killed proactively to protect livestock…or by ‘big-game hunters’ right here in the Star Kingdom who want a hexapuma head in their trophy room.”

She grimaced and tipped her chair back again.

“Like I say, it’s hypothetical right now—no one has sufficiently hard numbers to know what’s really happening out in the bush. But we do know that when an apex predator’s removed from its habitat it sets off a trophic cascade that can be catastrophic.”

“A…trophic cascade?” Nosey repeated, and she frowned.

“Essentially, the loss of an apex predator sets off a chain of effects that move down through lower levels of the food chain, frequently with disastrous consequences. That happened a lot back on Old Earth, and on some of the older colony planets, as well. If you eliminate something like the Old Terran wolves that preyed on elk, for example, the elk herds explode in numbers and overgraze their habitat until they destroy it and literally starve. That’s bad enough for them, but the destruction has a catastrophic ‘ripple’ effect on everything else that lives in that habitat, and that doesn’t consider the fact that the predators help keep the herd healthy by culling the old, the infirm, and the sick. Without that, disease spreads much more easily, especially in a herd that’s already weakened by starvation and the loss of habitat. The best ‘solution’ they could come up with in many instances back on Old Earth was to replace the natural predators with human hunters to keep the elk population under control. Eventually, they reintroduced predators into many of the wilderness areas from which they’d been eliminated, but the damage was often extreme before they could accomplish that.”

“And you think the loss of the hexapumas could do that to Sphinx?”

“I’m sure the notion that something as dangerous as a hexapuma needs to be ‘protected’ seems…odd, especially to someone who has to worry about being eaten by one of them!” Gwendolyn chuckled. “And it’s not as if we’ve had time for the sort of long-term studies that could produce hard numbers to prove that’s happening. But it’s the sort of potential problem we try to look ahead for, because once the disaster’s already happened, it’s hard to undo it. We think it’s a lot smarter to keep it from happening in the first place, if we can.”

“Well, I certainly agree with that!” Nosey said. “And if you can throw any of those ‘hypothetical’ analyses my way, I think there are some people on Sphinx who probably need to be thinking about the same sort of problems.”

“Which is exactly why I wanted to have this talk with you,” Gwendolyn said. “Oh, not specifically about the hexapumas. Like I say, that’s a long-term problem that may never actually arise. But just as we’re supporting the Explorers, we’re always looking for additional educational opportunities. From your coverage of the treecats, both before and after the Orgeson incident, you seem like a logical avenue for us to pursue. It’s obvious you care deeply about them, and no close friend of Stephanie’s or Karl’s is going to do anything to harm them.”

“You can absolutely count on that,” Nosey said firmly. “I hadn’t realized how smart they really are until all of us got caught up in that baka bakari mess.”

“Really?” Gwendolyn asked as casually as she could.

“Before the three of us—and the Schardt-Cordovas and the rest of Stephanie’s friends—got involved with stopping Orgeson, I’d thought of the treecats as adorable, really smart animals. In fact, I was worried—still am, really—about how the ‘aren’t they adorable’ quotient could lead to situations in which they need to be protected from human exploitation. To be honest, I was worried about what people like Stephanie might be doing that was actually detrimental to ‘their’ treecats, but she and Karl—and Jessica, and Cordelia—set me straight at least on that. The thing is, the ’cats are even smarter than I’d thought they were, and they aren’t really ‘pets’ at all. It’s more like a…partnership.”

“I know some people, including Clifford Mulvaney, are comparing them to service animals,” Gwendolyn said, and Nosey shook his head a bit impatiently.

“I know they are, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Steph and the others haven’t trained their friends to do the things they do. They do them because they’re so darned smart. Doctor Mulvaney’s right that they don’t have any way to actually communicate with us, but I’m convinced that if they did, they’d have a lot more to say than, say, an Old Terran dolphin or one of the Beowulf gremlins.”

“You’d put them that high on the sentience scale?” Gwendolyn asked, watching his expression carefully, and he chuckled wryly.

“I’m not any sort of xeno-anthropologist, so I wouldn’t begin to know where to put them on the scale. I’m just saying they’re a lot smarter than a lot of people—most people—give them credit for even now.”