- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

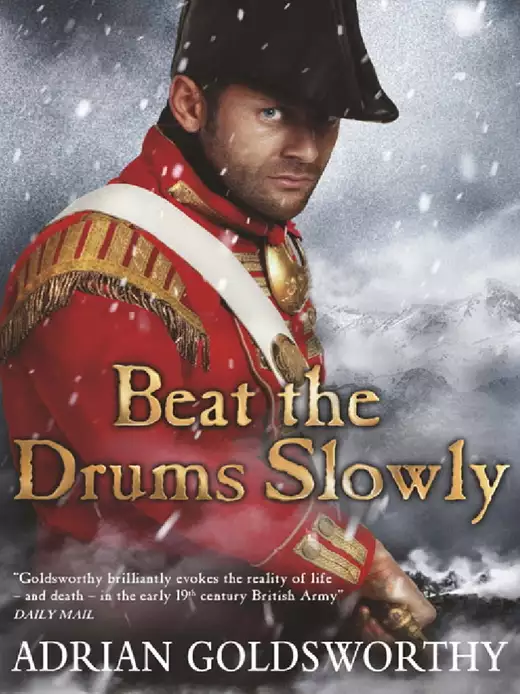

The second novel in a brilliant new Napoleonic series from acclaimed historian Adrian Goldsworthy. Second in the series begun by TRUE SOLDIER GENTLEMEN, the story takes our heroes through the winter snows as Sir John Moore is forced to retreat to Corunna. Faced with appalling weather, and pursued by an overwhelming French army led by Napoleon himself, the very survival of Britain's army is at stake. But while the 106th Foot fights a desperate rearguard action, for the newly promoted Hamish Williams, the retreat turns into an unexpectedly personal drama. Separated from the rest of the army in the initial chaos, he chances upon another fugitive, Jane MacAndrews, the daughter of his commanding officer, and the woman he is desperately and hopelessly in love with. As the pair battle the elements and the pursuing French, picking up a rag-tag band of fellow stragglers along the way - as well as an abandoned newborn - the strict boundaries of their social relationship are tested to the limit, with surprising results. But Williams soon finds he must do more than simply evade capture and deliver Jane safe and sound to her father. A specially tasked unit of French cavalry is threatening to turn the retreat into a massacre, and Williams and his little band are the only thing standing between them and their goal.

Release date: August 11, 2011

Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Beat the Drums Slowly

Adrian Goldsworthy

‘Come on, Williams,’ the man called back, trying to sound friendly even though it dismayed him that a fellow officer was so lacking in this essential accomplishment of a gentleman. ‘Not far now.’ His encouraging smile was lost in the shadow of his cocked hat and the gloom of the night. Cloud for the moment masked the bright moon, leaving only a faint glow off the snow-covered fields.

‘Doing my best,’ replied Ensign Williams, for although he disliked Captain Wickham and resented his condescension, he was obliged to respect his superior rank.

‘Go on, Bobbie! Go on, girl,’ he added more quietly. The mare flicked her head up, then tugged at the reins and took a couple of paces backwards. She did not like the look of the fast-flowing water, or perhaps it was the rushing noise and the clicks and reflections from the chunks of ice that had come from the mountains not many miles away. Williams prodded his heels against her side once again. Ears twitching, the horse began to turn away.

‘Get on with it!’ The impatience was obvious in Captain Wickham’s tone, his consciously suave demeanour beginning to crack. ‘We must not keep Lord Paget waiting.’

They were riding to join Lieutenant General Lord Paget, eldest son and heir of the Earl of Uxbridge and the commander of the cavalry forming the vanguard of the British Army. Wickham obviously relished using the title, and had already done his best to imply a degree of familiarity. Although belonging to the same regiment, the 106th Foot, the captain had been given a staff appointment back in August, secured through the offices of powerful friends. Williams had often wondered whether these knew or cared anything about the actual talents and character of the man whose advancement they fostered. Personally, he had seen enough of Wickham to despise him both as a soldier and as a man.

‘Use your whip, damn it!’

Williams had no whip, as indeed he had no spurs, although since he instinctively felt the latter to be cruel this caused no regret. His boots were the same as those issued to the ordinary redcoats of the regiment, as were his gaiters.

An ensign was the most junior of commissioned ranks in the British Army and Williams had been an officer for barely four months. Before that he was a Gentleman Volunteer, a man without friends to secure him a commission or the money to purchase one. A volunteer marched in the ranks, carrying a musket, wearing the uniform and doing the duty of an ordinary soldier. All the while he lived with the officers of the regiment, waiting until battle created a vacancy and he had shown sufficient courage to deserve it. Back in August he had fought the French in Portugal and both of those things had occurred. Not only that, but he had survived to receive the promotion.

Now it was just a few days short of Christmas in the year of Our Lord 1808, and the British Army had marched from Portugal into Spain. They were riding to join the foremost vanguard of that army, although Wickham had still not told him why he had been summoned from his battalion.

Pulling on the reins, Williams tried to guide the mare back towards the ford. Suddenly she went sharply in that direction, turning full circle.

‘Damn it, Bobbie,’ he muttered. ‘It’s only water.’ A religious man, who often seemed rather sombre when he was not with his few close friends, Williams rarely swore, but had always found that riding encouraged the practice. His friend Pringle had bought the bay mare from among the horses captured from the French at Vimeiro. It was a scrawny beast, for French dragoons took poor care of their mounts, and her left eye had been lost long ago to infection, leaving a gaping, empty socket. Yet she was normally willing, if insanitary in her habits – ‘likes pissing on her own hay’, was Billy Pringle’s verdict. He had christened her Roberta, but quickly shortened it to the less respectable Bobbie or even Bob.

‘For God’s sake!’ hissed Wickham. Waiting on the far bank, he was beginning to feel the deep cold of the night, and tugged his heavy boat cloak even closer around him. Williams wore nothing over his red jacket, with its ensign’s epaulettes and shoulder wings marking him out as a member of a flank company. Ensigns in the rest of the battalion wore only a single epaulette on the right shoulder. He possessed no cloak, and although his soldier’s greatcoat was warm enough, it was far too awkward to wear on horseback.

Big flakes of snow began to tumble lazily through the air. Even though the savage wind had gone, the night was still bitterly cold. Williams had always thought of Spain as a land where a tyrannical sun baked the earth in endless summer. Portugal had in truth been hotter even than that imagining. Yet the regiment had marched into Spain to face weeks of torrential rain, and now the temperature had fallen and the rain turned to sleet and snow.

Desperate, Williams reached back and slapped the mare’s rump. She protested, tossing her head, but still shot forward so sharply that he almost lost his balance. Then they were in the ford, icy water spraying up and drenching his trousers. She almost stumbled on the rutted slope at the far bank, but recovered and then was out.

‘There, that wasn’t so bad, was it?’ said Williams softly, patting the mare’s neck.

Wickham set off at a brisk trot as soon as Williams joined him on the other side, for it was better to be moving than standing in the cold. Even so, the chill seeped into the ensign’s soaked lower half. Soon Wickham’s affability was restored. He did not much care for his fellow officer, thinking him rather a dull clod of a man, somewhat inclined to surliness, and also knowing him to lack any useful connection. Yet it was always simpler to be on easy terms with people, and he avoided unpleasantness whenever possible. Wickham knew himself to be good at being pleasant. He dropped back a pace to be beside the ensign, and grinned.

‘Not as warm as Roliça, eh? Or as hot as the drubbing we gave the French that day?’

‘That was hot work,’ replied Williams flatly. That had been the regiment’s first action, a bitter scrambling fight up a warren of rocky gullies. Their colonel had been killed early on, along with several other officers, and more were wounded or captured. In spite of this they had taken the hill and held it, but little thanks to Wickham. The captain had been drunk by the time the advance began, and lay insensible before the battle was finished. Worse still, Williams had seen him murder a French officer who had surrendered. ‘A grim day,’ he added.

‘But glorious.’ In truth the captain remembered almost nothing of the battle, and was puzzled at his companion’s lack of enthusiasm. He changed the subject.

‘How are my grenadiers?’ Wickham had for a time commanded the Grenadier Company in which Williams had served as a volunteer and now as an officer. The grenadiers were the biggest soldiers in a battalion, awarded the place of honour on the right of its line. Wickham was a little above average height, and the straightness of his carriage and the skill of his tailor always made him seem taller again. Williams was a big man, more than an inch over six foot and broad shouldered. At the moment he was also very cold, and sore from riding for the first time in months. He merely confirmed that the company flourished, now led by Pringle.

‘Good old Billy,’ said Wickham, realising that he would have to labour at this conversation. ‘I do miss him and the other fellows. By the sound of it you should have Hanley back with you soon.’

That was good news, for along with Pringle, Lieutenant Hanley was Williams’ closest remaining friend in the regiment – poor Truscott still being in hospital at Lisbon after losing his arm. Williams nodded, but said nothing, and once again Wickham was forced to continue.

‘Hanley is a lucky fellow, doing duty with Colonel Graham.’ If Wickham had less esteem for a senior officer who was not a lord then he did not show it. After all, everyone knew that the elderly Graham had been wealthy enough to raise his own regiment. His rank was a courtesy, but his talent for diplomacy and ability to speak half a dozen languages had made him indispensable as the army had driven into Spain. Very few British officers spoke Spanish – or indeed any language apart from their own. Hanley was fluent, having lived for some years in Madrid, trying and failing to establish himself as an artist before poverty and the French invasion forced him to leave. Wickham had remembered this, and recommended him when the army commander was searching for Spanish-speakers. It had enhanced his own reputation as a man well suited to providing practical answers to a problem. Now he hoped to repeat the success.

‘It is quite remarkable to have two linguists in the same company,’ he said. ‘It rather belies the opinion of the rest of the army that we grenadiers are conspicuous for the size of our bodies rather than our brains.’

Williams was baffled. ‘Two, sir?’

‘No need to be modest. Hanley may be more accomplished from living over here, but I remember you embarked on a serious study of Spanish on the voyage from England, and no doubt have improved with experience. So when I discovered that Lord Paget had need of an interpreter, I could not help thinking of you. It will be no bad thing for your career to become known to such a distinguished officer.’

Dread flooded over the ensign. It was true that he had got hold of a Spanish grammar, and sought instruction from Hanley, and endeavoured to practise. So far his efforts had been rewarded with little progress.

‘Do you know what his Lordship requires me to do?’ It was a struggle to keep his voice level.

‘No idea,’ said Wickham blithely. ‘Don’t worry, old fellow. I am sure you will serve most handsomely. Don’t Billy and the others call you “Jack the interpreter”?’

Williams’ already flimsy confidence collapsed, and he silently cursed his friend’s sense of fun. The day after Vimeiro, in the full flush of excitement on gaining his commission, he had offered his services to a baffled official from the commissariat department, the civilian clerks who ran the army’s supply system. The man was trying and failing to explain to some local muleteers that he needed them to gather early the next morning with their animals. In his mind, Williams constructed a flawless instruction, perhaps a little more Spanish than Portuguese, but he felt that an appropriate accent would make the difference. According to Pringle – and Williams was convinced that his friend embellished the story on each of the many occasions since then that he had told it – he produced the following confident oration.

‘Portuguesios, the commissario – wants the mulos – tomorrowo – presto – la, la!’ Pringle accompanied each performance with fervent gestures and forceful expressions. At the time his friend, and the other officers in the group, had laughed so much that Williams doubted the accuracy of their recollection. He did remember the grave disappointment of the commissary, who reasonably enough felt that he could have done as much himself.

‘I am not sure my best is very good,’ was all that he thought to say now.

Wickham silently damned the man for his gloomy disposition, and decided that efforts at genteel conversation were wasted effort. Anyway, the cavalry brigade should not be far away now, and they could see a faint glow reflecting off the clouds from the chimneys of Sahagun up ahead.

‘Let’s push on,’ he said, and urged his expensive gelding into a canter. Williams kicked in his heels to follow, but Bobbie stubbornly refused to go faster. He tried again with more force, and the mare lurched, seemed to stagger, and then was running in her fast, jerky motion. The big man stood up in his stirrups to prevent the saddle slamming against him with every beat. Bobbie was awkward, but fast, and soon closed on Wickham.

They slackened pace when they saw a long dark shadow in the gloom. The moon emerged from behind clouds and they saw that it was made up of many shapes. They walked across some sort of bridge or causeway, and then, without a word, Wickham again surged forward. Williams used more force than before and when the mare took off in pursuit he lost his right stirrup. Fighting for balance as he was pounded by the saddle, he bounced in his seat and swayed from side to side, as they rode alongside the long column of light dragoons in their fur caps. No doubt the cavalrymen were suitably impressed by his horsemanship, but Williams was too concerned with his frantic efforts to stay on to spare this any thought. Somewhere he lost the other stirrup. His legs began to swing wildly.

Wickham reached the front of the brigade and reported to the general and his staff. A few moments later Williams arrived, sawing desperately on the reins. Bobbie decided to respond abruptly, skidding to a halt in a patch of mud topped by only a thin sliver of ice. Williams lost his balance and tumbled sideways, slumping down into the snow-and mud-filled ditch beside the track. The smell suggested that some of the horses from Lord Paget’s staff had added to the mixture.

There were sniggers, and a low comment of ‘Who gave you permission to dismount!’ – the ancient rebuke of regimental riding masters dealing with raw recruits unable to stay on a horse.

Bobbie stood meekly beside Williams, as he pushed himself up, something he did all the more quickly when she began to urinate noisily.

‘May I present Mr Williams, my Lord,’ said Wickham, unable to resist exploiting his subordinate’s discomfort. The cavalry officers laughed uproariously, until their commander raised a hand. Lord Paget was a handsome man, a horseman since boyhood, and wore the tight overalls and heavily laced, fur-trimmed jacket of the hussars with a perfection that Beau Brummell could not have surpassed. He was also a serious soldier and widely believed to be the ablest leader of cavalry in the King’s service.

‘To what do we owe this honour?’ he asked, the tone a mild rebuke to the effect that Wickham had forgotten his duties and not yet made a formal report.

‘General Paget’s compliments, my lord, and he understands that you have need of an officer able to speak Spanish.’ A younger brother, also a general and as widely respected, commanded the Reserve Division.

‘Does he? Well, yesterday you might have been useful, but we have other things to occupy us now. Still, you may as well stay for the dance.’

It took an effort for Williams not to cry out his joy. Even the shame of falling off his horse in front of the cream of the cavalry’s officers – and no doubt of London society as well – no longer mattered. He would not to be called upon to exercise his supposed talent as a linguist. He hauled himself back up on to the mare.

Lord Paget was peering at a fob watch, doing his best to read its face in the moonlight. ‘It’s time.’ He looked up at one of his aides. ‘Tom, do me the honour of riding over to General Slade, and remind him that he is to begin the attack from the north-west of the town at six thirty, and drive the enemy towards us.’ He turned to Wickham. ‘Take Mr …?’

‘Wickham, my lord.’

‘Take Captain Wickham with you. He seems to be well mounted. The other fellow can come with us.’

The two men rode away, cutting across the fields. ‘And pray God that bungler doesn’t make a hash of it.’ Williams was close enough to Lord Paget to catch his whisper, but did not know whom he meant. As the column moved off, he fell in at the rear of the general’s family of staff officers. A lieutenant with side whiskers almost as luxuriant as the general’s rode beside him and soon proved himself a friendly companion.

‘There are French cavalry at Sahagun. Maybe a brigade, but we can’t be sure. Probably foraging, or the far outposts of Marshal Soult’s army. So we’re off to wake them up a bit.’

‘We?’

‘The Fifteenth Light Dragoons, old boy,’ drawled the staff officer, who then turned to the man riding behind them at the head of a squadron. ‘Nearly as good a regiment as the Tenth Hussars.’ The officer behind them ignored the good-natured provocation.

‘The Tenth are my lot. They’re out there somewhere with Old “Black Jack” Slade. They drive the French from cover, and then it’s view halloo and sabres and glory before breakfast. Have you ever been in a cavalry charge, Williams?’

‘I confess not.’

‘The main thing is to stay on your horse.’ The hussar chuckled, and the mockery was so good natured that Williams happily joined in.

‘Quiet back there,’ shouted a voice far louder than their conversation. ‘We’re getting close now.’

The moon had gone, and the pale light of dawn was growing, although there was no sign of the sun. In the fields there were patches of milky-white mist. They rode on, hoofbeats mingling with the snorts and heavy breathing of the horses and the creak and jingle of harness to produce a noise so different from the sound of infantry on the march. If anything, the road was in worse condition than the stretch Williams and Wickham had come down. Patches of ice combined with deep ruts to make the going treacherous. Bobbie stumbled and skidded several times, as did most of the other horses. Several fell, although Williams did not see anyone badly hurt.

Muffled shouts and a single shot came from somewhere in advance of the main column. Minutes later, an hussar galloped up to report that the outposts had run into a French piquet, and killed two and captured half a dozen. Several more had escaped, riding back to give the alarm. Lord Paget led the regiment on, but progress was slow when they had to file across two bridges spanning a drainage ditch. Neither had a parapet, and their surface was slick with ice, but, to Williams’ surprise, Bobbie strode across without any hesitation or false step.

He could see the rooftops of Sahagun clearly now, and somewhere a bell was tolling.

Lord Paget took the 15th to the right of the place, following a fork in the road. As Williams looked across the fields to their left, he could see a dark mass formed outside Sahagun, perhaps a quarter of a mile away. There were horsemen there, but in the mist and gloom it was hard to know their strength. The cheerful hussar officer had no doubt about their identity.

‘Johnny Crapaud is up early for once.’

Lord Paget turned and gave the order himself. ‘Form open column of divisions!’ Cavalry drill was something of a mystery to Williams, and he had no idea whether a division was a troop or a squadron, but the intent seemed clear. As in the similar infantry formation, the regiment would march with sections one behind the other, with enough space between them so that each could wheel and form a single line either to the front or facing either flank.

The dark mass began to move as the 15th changed formation, heading eastwards away from Sahagun.

‘Walk march – trot!’ The general’s order was repeated down the extended column. The British cavalry advanced rapidly, moving parallel to the enemy, quickly gaining and then passing them. Small shapes came out of the darker mass as the French sent out flankers, individuals and pairs of riders, whose task was to screen the main force. They came close, and Williams could clearly see the outline of one man’s broad-topped shako. He was probably a chasseur, like the men they had seen in Portugal, and the counterparts to the British light dragoons and hussars.

‘Qui vive?’ a voice called out. The challenge was repeated.

‘Ignore them,’ said Lord Paget.

‘Well, we haven’t been introduced,’ hissed Williams’ companion.

‘Qui vive?’ The wind picked up, driving away the mist, and he could clearly see the French chasseur holding his carbine, and yet in spite of their refusal to answer, he did not fire. It began to sleet.

The main body of the French had stopped. It took a moment for the general to see this, and then he halted his own column. There was movement in the French mass as they deployed into line facing towards the British. The sleet turned to snow, then slackened and died away to nothing.

‘Qui vive?’ Still no answer, and Williams began to think the enemy outposts quite stubbornly obtuse. Behind him the 15th wheeled left to form line to confront the enemy. He remained with the general and his staff, ahead of and just to the left of the centre of the new line. A small escort of a dozen men from Lord Paget’s own regiment, the 7th Hussars, guarded him.

Williams reached down to loosen his sword in its scabbard, suddenly nervous that the frost would make it stick. It slid comfortably and he let it fall back into place. He had anticipated the order by only a moment.

‘Draw swords!’ There was a scraping as the hussars’ blades grated against the metal tops of their scabbards. The light cavalry-pattern sabre was curved and rather clumsy, but its heaviness lent power to the edge. Williams carried a Russian sword, less curved and lighter, but well balanced, and he was tempted as always to flick it through the air, enjoying its feel. Instead, he shouldered the blade just like the hussars. Williams had never fought with a sword, for in the battles of the summer his weapons had been musket and bayonet. He had shot and killed the sword’s owner, and now for the first time wondered whether it was an unlucky weapon. That was superstition, and he tried his best to dismiss the thought.

‘Vive l’Empereur!’ A cheer came from the French cavalry. Williams almost smiled to hear again the familiar shout. Then there were flashes and puffs of smoke as the flankers fired their carbines, the noise of the shots coming almost instantly as they were so close. Williams did not see anyone fall, and the French horsemen were soon spurring their horses back towards their main body.

Unscathed, the 15th gave a cheer of their own.

‘The Fifteenth will advance. Walk march!’ The line walked forward, the hussars in two ranks; the second waited until the first was a horse’s length ahead of them before following.

‘Emsdorf and victory!’ shouted the lieutenant colonel.

‘Emsdorf and victory!’ The chant was repeated all along the line, recalling a battle half a century before when the regiment had first made a name for itself.

‘Trot!’ They accelerated almost immediately, for the French were already less than four hundred yards away. Swords were still on the shoulder.

The French were not moving, and then suddenly their front vanished behind a cloud of smoke as they fired a volley with their short carbines. The range was long. Williams would certainly not have thought to fire at such a distance. He did not hear or feel any of the shots go near him and guessed that they all went high.

‘Charge!’ They was already closing quickly, and before he used his heels Bobbie began to run, for once without her familiar lurch. She raced ahead, and Williams was riding abreast of Lord Paget, a horse’s length ahead of everyone else. The general looked more puzzled than irritated when he glanced to see the infantry officer beside him.

Another volley, and this time a ball snatched the cocked hat from Williams’ head. A horse fell in the squadron behind them, the man tumbling to the ground, and somehow the hussar behind him jumped the fallen beast and man without checking. The men had their sabres high now, the point angled forward at the enemy. Williams was bouncing too much in the saddle to hold his own blade steady.

The French were close. In front were three ranks of chasseurs, their shakos protected by light-coloured cloth covers, and their dark green uniforms looking almost black in the dim light. Some were loading, fumbling with paper cartridges and metal ramrods, for even the short-barrelled carbines were awkward to load on horseback. Others clipped the guns back to their slings and reached for their swords.

Bobbie took off, leaping a ditch which Williams had not noticed as he focused on the enemy. The mare landed well, only an instant after Lord Paget’s horse, but Williams had not been prepared and almost lost his balance. Behind them the staff and escort, followed closely by the 15th, cleared the ditch and urged their mounts to one more effort, rushing at the enemy.

A few Frenchmen had loaded fast enough to fire again, and an hussar was plucked from the saddle, but there was already movement and jostling among the chasseurs. Their horses were stirring and shifting. Many turned away, instinct making them want to join the herd rushing towards them and run on with them. The riders were nervous, for they had expected a feeble probe by the atrociously mounted Spanish cavalry and not an enemy who charged boldly home. Their volleys had had no impact and now it was far too late to come forward and meet the charge.

Gaps opened in the formation and Williams felt a wild exhilaration as the last few yards thundered past in the blink of an eye. Bobbie shot into a space left by one of the Frenchmen pushing to the rear, barging against the rump of his horse. The man looked back over his shoulder at Williams, his face a rictus of horror. To the right a big horse, aggressively ridden by one of the general’s aides, knocked down a chasseur and his mount as they struggled to turn, but were trapped by the press behind. Lord Paget was cutting with his sabre, but as yet Williams could reach no one. Then he was through into the confusion that had been the French second and third ranks. A chasseur levelled his carbine, and the flame was enormous because it was so close and the ball took a chunk out of his right shoulder wing, knocking him back in the saddle for a moment.

Williams’ body turned and he flung his weight into a wild slash with his right arm. By chance rather than design the tip of the sword struck just above the chasseur’s collar, opening his throat to the bone. Blood sprayed from the blade as Bobbie surged on, finding a gap in the press, and Williams’ arm swung round until it was almost straight behind him before he could recover. Another Frenchman came at him from the right, but the man’s cross-bodied slash was misdirected, then another horse struck his own mount, and there was just enough time for Williams to duck beneath the blow.

The chasseurs were broken and running, although some still fought, and just behind them was another regiment. These were dragoons, with dark green jackets faced red and brass helmets with black horsehair crests, and they were also in three ranks. Fugitives from the chasseurs pressed into the formation, spreading panic and confusion, and with them came Williams and the first of the hussars, who gave a deep-throated roar that sounded more animal than human as they hacked with their heavy blades. One trooper screamed, and others grunted or sighed as they were caught by precise thrusts from the Frenchmen’s straight swords. Williams parried a blow and Bobbie was still going forward as, just like the chasseurs, the second French regiment’s horses chose to join the stampede. He was pressed so close to one dragoon that neither man had room to swing and the Frenchmen grinned at the absurdity of their predicament.

The hussars cut mostly at the heads of their enemies. Williams saw a man with his face slashed open from cheek to chin. Another was knocked from his horse by a blow which dented his brass helmet. The hussars’ own fur caps were reinforced with nothing stronger than cardboard, and offered little resistance to the enemy’s swords. Blade clashed against blade and the noise was like hundreds of coppersmiths all hammering at their work together, and all the while cursing and screaming at each other. More than one hussar was struggling to remain in his seat as their saddlecloths shifted. No one had remembered to halt the regiment and tighten girths before the charge.

Suddenly the press broke up. Both French regiments were running, swerving to the east and scattering into small groups. When the lines met, each side’s left wing had overlapped the enemy line. The hussars had wheeled at once to roll up the enemy. On the French left, a still-organised force of dragoons tried to cover the retreat, but they were quickly swept up in the mad rush away from the fight.

Bobbie ran with the flow, and Williams reckoned the mare was enjoying the wild excitement. Everything was happening so quickly and he was reacting by instinct, more than any thought, as the whirling mêlée surged across the snow. He cut at a Frenchman, missed altogether and almost lost his balance, but by that time he was past and approaching another man. Then he saw the man was wearing a round fur hat and realised that he must be one of the 15th so stopped his blow and urged Bobbie to pass to the man’s left. Williams nodded to the man as he passed, and was rewarded with an obviously French curse and the gaping muzzle of a pistol pointed in his face. He flinched, eyes snapping closed.

‘Look out, sir!’ came a cry, and then there was a deafening explosion, but Williams felt no blow, and when he looked the Frenchman in the fur colpak was spurring away, but a British hussar was sprawled almost at his feet, his dead horse crumpled behind him.

‘You daft bugger, Jenkins,’ said an hussar corporal, who then kicked his mount onwards. He was shaking his head as he passed Willia

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...