- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

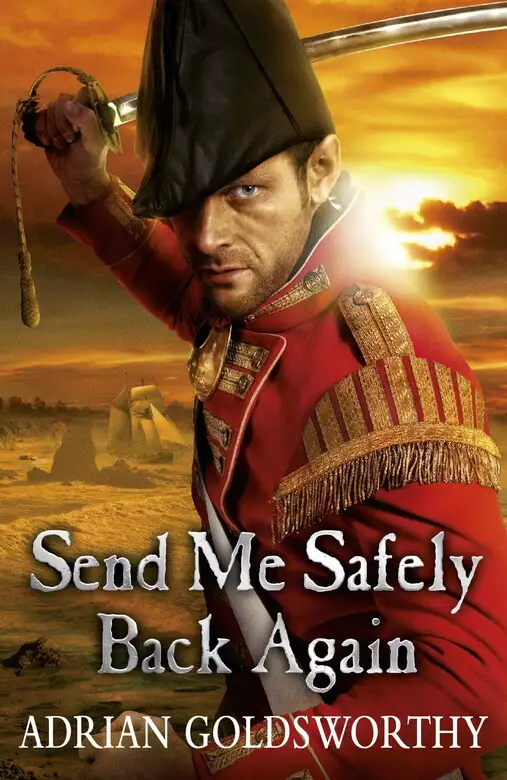

Synopsis

The third novel in the series sees new challenges for the men of the 106th Foot, as the British army attempts to recover from the disaster of Corunna and establish a foothold in the Peninsula. Featuring the battles of Medellin and Talavera, the 106th will have their mettle severely tested on the battlefield. But if Napoleon is to be ejected from Spain, war must also be waged in more covert ways. For Hanley, the former artist who is a more natural observer than fighter, the opportunity to become an 'exploring officer' leads him into even more dangerous territory, the murky world of politics and partisans. And while Ensign Williams seeks to uncover the identity of the mysterious 'Heroine of Saragossa', a conspiracy of revenge within the regiment itself threatens to destroy him before he's even faced a shot from the French.

Release date: August 9, 2012

Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Print pages: 369

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Send Me Safely Back Again

Adrian Goldsworthy

Lieutenant William Hanley of His Britannic Majesty’s 106th Regiment of Foot looked down at the great battle unfolding before him and knew that he was not wanted. Far more soldiers than he had ever seen in one place were stretched in a long crescent across the wide plain. There were Spanish regiments in white and brown and blue, and half a mile beyond them the darker masses of the French cavalry and foot. There were far more Spanish soldiers.

Hanley decided to draw. A tall man, he perched on the low stump of a shrivelled vine tree and crossed one leg over the other to rest his sketch pad. Soon his right hand was moving quickly across the page, caressing the paper as he shaded to give depth to the tiny lines of soldiers. The limits of his skill no longer frustrated him as once they had done. Hanley had lived in Madrid for years, studying art in the company of other passionate young men who believed themselves to be creative and despised those who were not. In those days his constant failure to capture on canvas the images in his mind enraged him. Now, he could sketch or paint for the sheer pleasure of the act, the old dream of artistic greatness long gone.

The death of Hanley’s father merely confirmed the end of that episode in his life, since his half-brothers had immediately cut the allowance paid to their bastard sibling. Hanley fled the French occupation of Madrid and returned to England with barely a penny to his name. Many years before, when he was just an infant, his father had bought him a commission in the army as a source of income, before such abuses were stamped out. Left with no alternative, Hanley found that he had to become a real soldier. He still found it difficult to see himself as especially martial, and struggled to understand many of his duties, but at least he no longer tortured himself because he was not a great artist. Indeed, his new life made him surprisingly content.

A thought struck him, and he wrote, ‘The plains before Medellín, 28th March, 1809’ at the top of the page. The picture would be a true record, if nothing else.

A groom glanced at the Englishman and paused as he brushed down a horse with an ornate saddle and lavishly decorated saddlecloth. The man had the very dark skin of an Andalusian, and although he was still young his black hair was streaked with grey and currently covered with dust and loose hair from the white horse. He shook his head in bafflement at the eccentricity of the foreigner.

Hanley nodded amicably to the man and then turned to look behind him at the redcoat standing watching over their own three mules.

‘How is he, Dob?’

‘Sleeping like a baby, sir,’ replied Corporal Dobson, his battered face creased into a smile.

The loud snore that followed lacked any infant-like quality, but confirmed that Hanley’s friend and fellow officer, Ensign Williams, was indeed still asleep. Dobson had fixed his bayonet on to his musket and driven the point into the hard earth. Then he had stretched the shoulders of his greatcoat between its upturned butt and the branch of another stunted vine, giving some shade from the noon sun to the officer as he lay in a shallow hollow to rest. Williams’ wide-brimmed straw hat covered his face.

Hanley felt pleasantly warm, for he revelled in the heat and found it hard to remember the snow and bitter cold of three months ago, when the 106th and the rest of the British Army had retreated through the mountains, pursued by Napoleon’s army. Their Spanish allies beaten, Sir John Moore’s British had run to the sea to take ship and escape. Already the horrors of that march seemed unreal to Hanley.

‘Think he’s over the worst of it now,’ Dobson concluded, snapping Hanley’s thoughts back to the present. ‘Still tired and weak, but he should be himself again soon. God help us,’ he added out of habit, but his expression betrayed his deep fondness for the dozing officer.

Williams was shy, rather pious, and seemed a natural soldier. Hanley was unlike him in almost every respect, and yet they were close friends, although he had to admit that the man had not been congenial company in the last few weeks. With a Welsh father and a Scottish mother, Hamish Williams had cast a profound and most definitely Celtic gloom over all those around him. His mood had not been helped by an attack of dysentery, and the ensign was still weak. The ride to get here had been long and exhausting, bouncing on the uncomfortable saddles of the mules which the alcalde of the small town had sworn were the only available mounts.

Hanley, Williams and Dobson were part of a detachment of their regiment whose ship had been blown back to Portugal instead of returning to England with the rest of the army. The commander in Lisbon had happily employed these additional soldiers, and two weeks ago had sent them into Spain again to secure some supplies left behind in Moore’s campaign. Hanley and the others had ridden ahead to the headquarters of the Army of Estremadura to seek assistance in their task.

They arrived to find their Spanish allies advancing to attack Marshal Victor’s French Corps, and with a battle to fight the three redcoats had so far not found anyone with time or inclination to deal with them. Hanley did not mind, for he rather suspected that he was witnessing a miracle, for the French were being beaten.

Last summer the Spanish had forced a French army to surrender at Bailen, and the British had beaten the French in Portugal. In the autumn, Napoleon himself crossed the Pyrenees with a quarter of a million of his veterans. One after another the Spanish armies were shattered in ruin, and the British chased away. There were no more victories, even after the Emperor himself went back to France and left the mopping up to his generals. A few months ago it looked as if nothing could stop the French from overrunning all of Spain and Portugal.

Somehow the Spanish armies had recovered, and now one of them was attacking and the outnumbered Marshal Victor was retreating. Hanley could sense the excitement in the men around him. They were mostly grooms, servants and a few junior officers from General Cuesta’s staff. The general himself, and everyone of real importance, was off inspecting the battle line. He was expected back soon, and so Hanley and the others waited for him, instead of chasing him around the field on their weary mules.

A group of grooms cheered suddenly as a squadron of French cavalry wheeled about and retreated, throwing up great clouds of dust. The Andalusian noticed Hanley once again, and clearly disapproved of this phlegmatic Englishman who sat and drew pictures when he should have been cheering on the victory. He removed his cheroot to spit on the grass, and then shook his head again.

‘Jesús, Maria y . . .’

Hanley could not help smiling when the man stopped halfway through the oath. Patriotic Spaniards were no longer so willing to invoke the name of Joseph, ever since the French Emperor had placed his brother Joseph-Napoleon on the throne of Spain.

The groom thought for a moment. Hanley’s Spanish was fluent enough to catch the muttered words. ‘And the one who was the father of our Lord on earth. Not the hunchback usurper.’ The man spat again, and crossed himself. Pamphleteers depicted the new king as a one-eyed hunchback of monstrous appetite for food, wine and women.

‘Looks like their general’s coming, sir,’ said Dobson. Hanley followed his gaze and noticed a colourful cavalcade of horsemen trotting briskly across the fields towards them, although still a few minutes away.

‘Our allies are doing well today. The French are going back everywhere.’

‘Aye, sir, they are. But no quicker than they choose to.’ The veteran was knocking out the embers from his clay pipe, evidently deciding that the arrival of senior officers of whatever nation required a degree of formality.

It was obviously a common instinct, for there was a bustle of activity among the grooms and servants. Fresh horses were brushed down and their tack quickly inspected. Other men prepared jugs of lemon juice or wine to quench the thirst of the approaching officers. Hanley paid little attention, and instead set down his pad and stood up, pulling at the front of his cocked hat to better shade his eyes. Out on the plain, some French cavalry were advancing.

The British officer extended a heavy telescope. A present from Williams’ mother to her son when he enlisted, it was intended to be mounted on a tripod, and it took Hanley a moment to steady the heavy glass. The effort was worthwhile, for the magnification was excellent. He could see the French cavalry in dark uniforms, and when one of the leading squadrons wheeled to alter its line of advance, a row of flickering dots shone off brass helmets. That meant that the cavalry were dragoons. Hanley smiled to himself, for part of him had come to take a delight in the colourful uniforms worn by the different armies, although personally he struggled with the military obsession for neatness.

There was another twinkle of light, repeated by each of the three squadrons behind the first as the men drew their long, straight swords. It suggested a considerable complacency and confidence that the French officers were only at this late stage ordering their men to ready their weapons. The leading squadron began to go faster.

Hanley shifted his gaze a little. A Spanish battery of six cannon was deployed between two regiments of infantry in drab-coats. The French cavalry came closer, going from trot to canter.

Then the guns fired. Hanley was sure he saw tongues of red flame spit from the distant muzzles before all was lost in thick clouds of dirty smoke. The lines of infantry fired a moment later, adding to the dense bank of powder smoke and blotting the French from sight. The range seemed long for muskets, but the drab-coated battalions were not moving and looked steady. Then he saw French dragoons retreating, no longer in neat ranks, but as little knots of individuals.

At that moment the noise of the firing came like the rumbling of an approaching storm. Williams sprang up, suddenly awake, his hat falling to the ground, but then he wrapped his head in Dobson’s greatcoat, pulling its sleeves off the branch and musket, and plunging himself into darkness. Muffled cries of alarm and rage came as the ensign fought with the coat, and succeeded only in more tightly entangling himself.

Hanley watched in amusement as his friend struggled. There was chuckling from some of the grooms and servants, and the lieutenant found it infectious until he dropped the telescope and doubled up with laughter. Several of the closest horsemen from the general’s staff were watching aghast, but he paid them no attention.

‘Jesús, Maria y Joseph,’ said the Andalusian, too astonished to stop himself from saying the last name.

Williams finally won the battle and flung the coat down. He was breathing heavily, his gaze wild eyed. Then he realised where he was and began to recover. A brief flash of anger at his friend’s almost hysterical amusement quickly subsided and he found himself smiling ruefully. He tried to ignore the expressions of amused contempt from the surrounding Spanish, who had only been confirmed in their low opinion of the heretic English.

The ensign cleared his throat. ‘Any water, Dob?’ he asked.

The veteran proffered his canteen. ‘Bad dreams, Mr Williams,’ he said softly.

Williams nodded, and then gulped down a good third of the warm, brackish liquid. He cupped his hand, poured in some water and then splashed it on to his face. Handing back the canteen, the ensign ran his hands through his fair hair, smoothing it into some sort of order.

Wrenched from sleep, he had mistaken the cannon fire for thunder and in his mind returned to the horror of the storm almost six weeks earlier. He, Hanley and the others had seen little, entombed below decks in their tiny cabin. They had felt the pitching and rolling of the transport ship growing greater and greater, seen the white flashes, and heard the peals of thunder and the dreadful crack when part of the mainmast was shattered, and suddenly the deck was lurching as if giant hands were flinging the Corbridge like a child’s toy. It had seemed an age before the violence began to subside. Several soldiers had been injured and one man was dead, his uniform and skin badly scorched, and his bayonet melted just like lead. The smell of cooked meat was sickening.

Williams shook his head to clear the memory. ‘I think I shall learn to swim,’ he told Hanley, who had at last recovered from his hysteria.

‘This seems hardly the place or the time. Although there are the rivers, I suppose.’ The plain was flanked on one side by the wide Guadiana and on the other by a tributary. ‘However, Billy tells me that many naval men consider that learning to swim is profoundly unlucky.’ Their friend Billy Pringle commanded the Grenadier Company of the 106th in which Hanley, Williams and Dobson all served. Pringle’s poor eyesight had kept him from following the family tradition of serving in the Royal Navy. Hanley still found it more than a little odd that the army had no objection to such a weakness.

‘Easier for him to be complacent. After all, some of us are more naturally buoyant than others.’ Williams gave a grin, and that was good to see for it had been rare enough these last weeks. Pringle was a little less tall than Hanley, who in turn lacked an inch or so on Williams, but Billy was a large man, whose girth remained undiminished by the rigours of two campaigns.

‘Damn me, if it isn’t Mr Williams! We witnessed your dance just now, old fellow. Some local fandango, I presume! And Hanley too. This is a delightful surprise.’

The voice was immediately familiar, if wholly unexpected, and none of them had noticed the approach of the three horsemen from the wider mass of General Cuesta’s entourage. Wickham was beaming with every show of sincerity, and clear enjoyment of Williams’ recent embarrassing display. Another officer from the 106th, George Wickham, was mounted on a nervous chestnut whose every line proclaimed it to be a thoroughbred. The other horses looked tired, and sweat stained, whereas his gelding seemed barely warmed up. Wickham’s cocked hat was high and obviously new, his uniform jacket was bright scarlet and beautifully cut, his tight grey overalls were trimmed with a row of gleaming silver buttons, and his boots were polished to a high sheen. George Wickham looked every inch the fashionable military gentleman. His back was straight, and although not too much beyond average height, he looked taller. His thick brown hair and luxuriant side whiskers only added to his strikingly handsome face and utterly confident demeanour.

Williams loathed the man. He knew Wickham to be a scoundrel and strongly believed that he was a coward. Hanley’s feelings were less intense, and he found Wickham pleasant enough company although wholly self-interested. Both of them had assumed that he was in England.

‘This is indeed a great surprise, Mr Wickham,’ said Hanley.

‘Good day to you, Captain Wickham,’ added Williams, who genuinely believed that there was no excuse for discourtesy. Part of him was desperate to ask Wickham for news. They had received no word of the rest of the regiment since they were swept back to the Portuguese coast, and indeed it was more than likely that their own survival was unknown. As far as they could tell the bulk of the fleet had reached Portsmouth without loss, but Williams longed for certain news that the 106th had got home – most of all that their commander, and his wife and daughter, were safe. He loved Miss MacAndrews with a passion that had only grown as the months passed. All his hopes for happiness rested on her, although their last meeting had ended in an angry refusal of his proposal, and he did not know whether those hopes were forever dashed.

‘Ah, actually it’s Major now,’ drawled Wickham complacently. ‘My brevet came through at the start of the month, before I left England.’ The newly minted major dismissed their automatic congratulations with becoming modesty. ‘Gentlemen, may I present some members of my old corps . . .’

One of his companions cut in. ‘I am well acquainted with Mr Hanley already, and it is a great pleasure to see you again,’ said Ezekiel Baynes, a round-faced, portly civilian, who looked like a cartoon John Bull sprung to life. Ostensibly he was in the wine trade, but many years of commerce in Spain and Portugal had allowed him to be of service to the government. Hanley had met him in the autumn, when army officers able to speak Spanish were in great demand. ‘Do you recollect that I mentioned Hanley to you not long ago, Colonel D’Urban?’ This was to the third rider, an officer with the laced blue jacket and fur-trimmed pelisse of the light cavalry. The colonel was in his early thirties, with a slim face, long nose and bright eyes that suggested a quick intelligence.

‘I am glad to see you, Mr Baynes,’ said Hanley with a smile. The merchant was good company, although he suspected that his bluff exterior veiled a mind which was both sharp and probably ruthless.

‘This is Ensign Williams, also of our Grenadiers.’ Wickham was somewhat put out to have lost his control of the conversation, but made the most of what little was left to him. He considered Williams to be a rather dull lump of a man, lacking accomplishments or notable friends. ‘This time last year he was a volunteer in the 106th.’ A Gentleman Volunteer was a man who lacked the money to buy an officer’s commission or the friends to secure one for him. He served in the ranks, wore the uniform of the ordinary soldiers, but lived with the officers, waiting for battle to create a vacancy. If Wickham had intended to inform his companions that the fair-haired officer was a man of little standing, he failed.

‘Promoted for gallantry, no doubt,’ said D’Urban enthusiastically. ‘Yes, of course, your regiment did splendidly in Portugal. Let me shake your hand, Mr Williams.’ He reached down and took the ensign’s hand in a hearty grip.

‘You must tell us all about your exploits,’ added the genial Baynes, his red face once again radiating honest joy. ‘And what brings you to us now?’

There was no chance to answer, as a Spanish officer urged his fine Andalusian mount alongside the three Englishmen. ‘Excuse me, your excellencies, but the general is to address his officers. Would you care to follow . . .’ He stopped, obviously astonished. ‘Guillermo! It is you, isn’t it? Holy Mother of God, I’d never have believed it.’

The recognition was not instant. It took Hanley some time to see past the heavily braided white coat, the gold sash and the round hat with its brass plate proclaiming ‘Long live Ferdinand VII – Victory or Death!’ to recognise Luiz Velarde, one of the circle of artists he had known in Madrid. It was hard to detect much trace of the loose-limbed, shabbily dressed sculptor in this dashing officer. Yet the eyes were the same, and immediately confirmed his recognition, for there was the same mix of quick humour and passion, and yet all the while the sense that the soul behind them was impenetrably veiled.

‘Luiz,’ he began, but then their mutual surprise and reunion had to wait, for a voice called for silence and all who were able turned to see the general.

It was the first real glimpse Hanley had had of Lieutenant General Don Gregorio García de la Cuesta, and the first thought that struck him was how old the man looked. He wore a powdered wig, which reinforced the impression of a relic of a bygone age. Yet he sat his horse well, and his gorgeously laced and gilt uniform graced a body still straight. For all his years – Hanley guessed that the general was nearer to seventy than sixty – there was the vigour and determination of a much younger man. Advancing years looked to have made the Spanish commander tough rather than frail. His words were positive, delivered in that rapid, deep tone that was so characteristically Spanish. Hanley translated quietly for Williams’ benefit, for his friend still understood little of the language. He noticed that Wickham was also paying attention to his explanations.

‘Marshal Victor is trapped with his back to the river. There is only the single bridge in Medellín and it will take time for all his guns and men to file across that narrow crossing. So he must fight, and when we beat him his army will have nowhere to go and will be destroyed. The only advantage the French have is in their horsemen. We have a river on either side of us, and they cannot sweep round our flanks. They can only come at us head on and meet our shot and steel.’

The general swept his audience with a fierce, determined glance.

‘Honoured gentlemen,’ Hanley continued to translate. ‘The whole army will continue to attack.’ There were enthusiastic murmurs from the senior officers. ‘Urge your men on and lead them to victory. God is with us!’ A tall priest sat astride a donkey just behind the general, backed by a row of friars. All now bowed their heads in prayer. Many of the officers crossed themselves.

‘This is the beginning. When we smash Marshal Victor the road to Madrid will lie open. The atheists will be driven from the sacred soil of Spain and His Most Catholic Majesty Ferdinand VII restored to his rightful throne. The days of revolution and the rule of the mob are over. Spain will be restored. Let us take back what is ours.

‘Follow me to victory! For God, Spain and Ferdinand VII!’

‘For God, Spain and Ferdinand VII!’ The shout resounded as the officers, and even the grooms and servants, cheered. Hanley could not help joining in as the cry was repeated. ‘For God, Spain and Ferdinand VII!’ The other British officers cheered in their native fashion, although Williams’ enthusiasm was muted.

‘It is a little peculiar for a commander to explain his intentions at so late a juncture,’ he said quietly.

‘Perhaps for your army,’ said Velarde. Hanley had forgotten – if he had ever known – that he spoke good English. In Madrid they had always spoken in Spanish. ‘Not so peculiar for us, and especially for the lieutenant general.’

Neither Williams nor Hanley showed any sign of understanding. Velarde lowered his voice so that they could barely hear him. ‘In the last year Don Gregorio has faced an angry crowd determined to hang him if he did not do what they wanted, and since then he has led a revolution, failed, and been a prisoner.

‘The cry of “Treason” is a common one these days, and often fatal.’ That at least they knew. Spanish generals whose untrained and badly equipped armies had fled from the French had more than once been lynched by their own men. ‘These are dangerous days,’ Velarde continued unnecessarily. ‘But today we should win!’ His enthusiastic smile was back.

‘I trust your task is not urgent?’ asked Colonel D’Urban, leaning down to speak to Hanley.

‘No, sir, we are tasked with recovering stores.’ There was activity all around them. Spanish officers were changing to fresh mounts and some were already heading off bearing orders to the divisions.

‘Just the two of you?’ said Baynes archly. ‘Oh, and your man, of course,’ he added, and Williams could not help finding a little disturbing the ease with which everyone had ignored Dobson.

‘There are two companies of our battalion under the command of Captain Pringle, three days’ ride to the north. He sent us down to Badajoz in case the Spanish authorities there could help us. Instead they sent us here,’ explained Hanley, and then lowered his voice. ‘There was a particular concern that a magazine of shrapnel shells should not fall into the wrong hands.’ Colonel Shrapnel’s new explosive shell was a secret of the British artillery, used for the first time and with great effect last summer.

D’Urban nodded, and then gave an impish grin. ‘Of course, but there will be plenty of time to deal with the matter after we have run Marshal Victor to ground. And in the meantime you fellows can make yourselves useful.

‘Wickham, you are the best mounted of all of us on that hunter of yours. Hanley speaks Spanish, so take him with you and go over to the far right. The Duke of Alburquerque’s division holds that part of the line. Report to him and observe the fighting. Obviously, do anything you can to assist our gallant allies.’

Major Wickham had arrived the day before, newly attached to the British mission to General Cuesta’s army. It baffled D’Urban that a man unable to comprehend more than a few words of Spanish had been chosen for the task. Wickham’s French was good, but many senior Spanish officers could not speak the language. Others, like Don Gregorio himself, refused to do so. Wickham’s usefulness in other respects was yet to become apparent. He was certainly a personable fellow, and perhaps this was seen as sufficient qualification for his task. More probably, he had powerful friends advancing his career – or perhaps just eager to have him outside the country.

D’Urban tried without much success to dismiss that uncharitable thought. At the least, the man ought to be capable of taking a look at the performance of the Spanish. It was important to judge the mettle of their allies, and see best how Britain could aid their cause.

‘Perhaps Major Velarde would accompany you?’

The Spaniard nodded. ‘An honour, your excellency.’

‘Splendid. Now, Mr Williams, I would like you to go with Mr Baynes and take a look at the left wing, over there, near the River Hortiga. He is only a civilian, and they are rarely safe to be let out on their own, so look after him as if he were a child. Restrain him if he gets any dangerous urges – such as peering down the muzzle of a loaded cannon! Take your man with you. What is your name, Corporal?’

‘Dobson, sir.’ The veteran had stiffened to attention and barked out the reply.

‘You look like you have seen plenty of service.’

‘Aye, sir, a good deal.’

‘Wonderful. In that case you keep an eye on them both and stop either from doing anything foolish!

‘Time to go, gentlemen. I shall remain with the general’s staff and go where he goes. I wish you all the joy of the day.’ With the slightest flick of his heels, D’Urban set his sturdy cob moving.

Dobson unhitched the reins of their mules from a vine branch and brought the animals over. Hanley’s mount bucked and snapped in protest at being forced to stir from rest so soon. The others simply stared mutely, chewing at mouthfuls of thin grass.

The three men were grenadiers, the tallest soldiers in the battalion, and their feet reached almost to the ground when they sat in the rudimentary saddles, legs dangling as there were no stirrups. Their uniforms failed to create a better impression. Both officers wore the same jacket in which they had landed in Portugal last August. Faded by sun and drenched in snow, rain and storm, they were badly frayed and heavily patched. Williams had cut off the long tails of his coat so that at least the patches were red. Purchased in an auction of a dead officer’s effects, the coat had never fitted him well, even before his recent illness. The sleeves of Hanley’s jacket were sewn up with brown Portuguese cloth. His hat was at least military, but now rose to a low, misshapen crown. Williams’ broad-brimmed straw hat shaded his eyes and protected his fair skin from the sun, but little more could be said for it, other than that it was marginally more respectable than his ruined forage cap. His cocked hat had long since been lost. As he sat astride his mule, his bent legs accentuated the almost transparent cotton on the knees of his trousers, showing the skin beneath.

Dobson wore the poorer-quality, duller red coat of the ordinary soldiers, now faded by the sun to a deep brick red. His shako was battered and lacked the white plume marking him as a grenadier. His issue trousers had decayed beyond salvation and been replaced with a pair in dark blue that he had foraged from an unknown source. These were already ragged and sewn up with patches of brown and black cloth. Only his boots were fairly new, well polished, and worn no more than enough to be comfortable. Cut off from the main body of the regiment, and their pay months in arrears, the companies of the 106th stranded by the storm had been unable to re-equip and reclothe themselves fittingly. Only boots had been issued, and they were glad enough to get them, for their existing ones had been worn to destruction in the winter’s campaign.

In spite of his worn uniform, the veteran at least cut a proud martial figure. A country lad in his distant youth, he rode the mule comfortably, his well-cleaned and maintained firelock slung over his shoulder. Williams also carried a long arm, but had to keep grabbing at the stock to stop the musket from slipping off as he sat far less confidently on his own mount. He had no sash, and only his sword – a very fine, slightly curved Russian blade – confirmed that he was an officer.

‘It makes you proud to be British,’ said Ezekiel Baynes, gazing at this reinforcement to the British mission.

2

Wickham gave the tall horse its head, racing off across the hard earth, hoofs brushing aside the long grass. Hanley guessed that the elegant officer was none too keen on being seen with so inelegant a figure as himself. Velarde barely kept up with the chestnut hunter, and his own mule refused to move any faster than a walk, in spite of repeated efforts to kick or slap it onward

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...