- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

It's 1811. Wellington has finally driven Napoleon's armies from Portugal, but the cost has been high. Fearing a French counter-attack, the British must rally their tired men and go on the offensive. Lieutenant Hamish Williams of the 106th Foot relishes the call to action. Spurred on by the prospect of at last redeeming himself in the eyes of Jane McAndrews, he hopes for a battlefield promotion. But Williams is marching into the bloodiest battle of the war - Albuera. As entire regiments are destroyed in the desperate pursuit of victory, the fate of Williams and his comrades hangs in the balance . . .

Release date: June 11, 2015

Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Print pages: 369

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

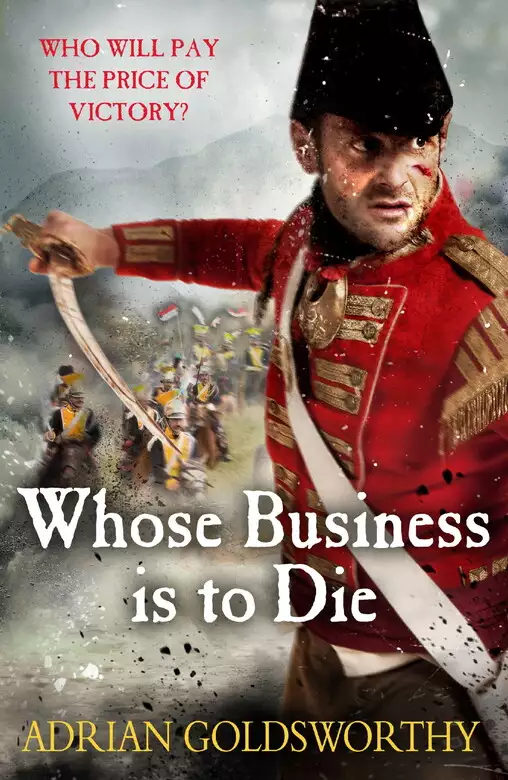

Whose Business is to Die

Adrian Goldsworthy

‘Well done, girl.’

Lieutenant Hamish Williams patted his grey mare on the neck and then arched his stiff back. An inch or more over six foot, he was a big man and powerfully built, and this impression was reinforced because the horse was a short-necked, clumsy-looking beast of barely fifteen hands. Yet for all her ill-favoured looks, Francesca had proved a good purchase, for she had plenty of stamina and was showing herself to be uncommonly sure footed. His other horse, a chestnut gelding with the graceful lines of an Andalusian, was proving less good, and had already gone lame in its offside front leg.

Williams reached inside his heavy boat-cloak and pulled out his watch. It was almost ten minutes past twelve on the morning of – and this took a few moments of calculation in his weary state – the twenty-fifth of March in the year of Our Lord Eighteen Hundred and Eleven. The watch, like the horses and the new uniform he wore under his cloak, was one of his Lisbon purchases, part of those wild two days when he had spent more money than ever before in his life. The only thing he had failed to find was a good glass, to replace the one the French had taken last year. Intended to be mounted on a stand, it had been a clumsy, heavy weight to carry strapped to his pack, but the magnification was so wonderful that it had seemed worth it. More than that, it was a present – and one she could not really afford – from his mother when, much against her wishes, her only son had gone for a soldier. He still had not had the heart to write and say that it was lost.

Williams looked back over his shoulder, but there was no sign of the leading company. If they did not appear in five minutes then he would have to ride back to find them, but he had not long left them and they should not have gone astray. He really ought not to have to wait long. Looping the reins over his left hand, Williams plucked off his oilskin-covered bicorne hat and ran his other hand through his fair hair, blinking as the fatigue washed over him. His chin felt as rough as sandpaper, although in truth only the closest observer would have seen that he had not shaved. Three years of campaigning in all weathers had given just the slightest dark tinge to his fair, freckled skin, although there were a few black flecks of powder encrusting his right cheek from where he had fired a musket more times than he could remember. Even so, with his bright blue eyes and fresh face, the lieutenant still resembled an overgrown schoolboy more than a veteran soldier.

The infantry did not appear, and to stop himself from hurrying back to search for them and risking appearing nervous, he unclasped his cloak and rolled it up to fasten behind his saddle. He would have to remember to shake it out and dry it later on – or ask his soldier servant to do it. Having a servant was as much a new experience as possessing a watch and two horses, so such thoughts did not come naturally to him.

‘Ah, better late than never,’ he said out loud as a rank of soldiers marched over the rise a couple of hundred yards behind him. ‘Earth has not anything to show more fair,’ he added, and then tried to remember where he had read the line. Not Shakespeare, of course, but someone modern. It was probably something a gentleman should know, although literary knowledge – indeed knowledge of any sort – was scarcely the boast of many good fellows, let alone the thrusters, in the army. Williams felt his want of education keenly, and wished one of his particular friends from his own regiment were here to ask. Pringle, Hanley or Truscott would no doubt have known – and would not mock him for his ignorance.

There was an officer walking to the right of the front rank, and when his cloak parted for a moment it gave the briefest glimpse of his scarlet coat, but that was almost the only dash of colour. The men were a drab sight in their grey greatcoats, shoulders hunched and heads bowed as they walked. They had been marching for seven hours, with only the usual short rests every hour, and most of the time they had faced driving rain and a road churned to mud by the cavalry who had preceded them. Their trousers, which were almost any shade of brown, blue, grey or black rather than the regulation white, were uniformly red-brown from mud, and more mud was spattered on the long tails of their coats. Muskets were carried down low at the slope, an affectation of the light bobs that he had always found less comfortable than slinging the firelock from his shoulder.

Williams doubted anyone back home would see the little column as fair in any way, the dark figures marching across muddy fields on a grey day. Many Britons rarely thought about their soldiers, save perhaps to puff themselves up when news came of a victory, and there had been few of those for some time. If they saw them at all it was in the shining splendour of a parade or field day, or in coloured prints where neat lines of men directed by officers on prancing horses fired or charged through the smoke. The soldiers in those pictures were as immaculate as their formations, and fought their battles in picturesque landscapes with mountains rearing in the background. Williams had seen prints of Vimeiro and Talavera and had seen nothing that reminded him in any way of those grim fights.

The officer watched the column come closer, and saw the head of the second company following on behind. He did not know these men, for he had arrived with the brigade only three days ago, but he knew plenty like them. Back in ’08 he had joined the army as a volunteer, a man considered a gentleman but without the influence to secure an officer’s commission or the money to purchase one. He had carried a musket, worn the uniform of a private soldier and done duty in the ranks while living with the officers. Those had been strange days, ending only when he survived Vimeiro and was rewarded with an ensign’s commission, and they had left him with a deep respect for the redcoat as well as an affection almost idolatrous in its intensity.

‘Anything to show more fair,’ he repeated under his breath. Was it Byron? It sounded sufficiently overblown for the aristocratic poet, but he did not think that was right. His taste stretched far more to the classics. Miss MacAndrews would know, and would tease him for not knowing. The thought of the girl brought back the familiar pangs of anger and despair. Keep occupied, he told himself, work until exhaustion blots out all feelings and thoughts. Think about poets or any other nonsense when there was nothing else to do.

Well, whoever it was would no doubt have raised a perfumed nosegay to shield himself from the sight and the wet earthy smell of the approaching light infantrymen. They were small men in the main, many young but aged by wind and weather, trudging along, not wasting any effort on unnecessary movements or chatter, not even thinking very much about anything. Williams had been on plenty of marches like this one, had known the discomfort of the issue pack which always hung heavy and too low so that its straps burned into the shoulders and pulled at the chest. Just keep going, place one foot in front of the other, loosely in step, not for the look of it, but because it was unconscious habit and made it easier not to tread on the heels of the man in front.

No one back home would ever see them like this, dirty and dishevelled, the locks of their muskets wrapped tightly round with rags to keep out the damp. Like the rest of the army they were bound to be infested with vermin from living in the fields or sleeping on filthy straw in dirty houses and barns. All too many of them would drink themselves senseless at every opportunity, duty and suffering alike forgotten for the moment.

No one back home would ever see them standing in ranks as friends dropped around them, ripped to shreds by shot and shell, or watch as they went forward into the smoke, faces pale but determined not to let each other down. He had seen such men fight and win when all seemed lost and, if they were not pretty, then they were magnificent.

Maybe it was better that Britons never saw them like this, he thought. No one at home had earned the right.

‘Morning,’ Williams called as the officer led the first company up to him. The man nodded in acknowledgement.

Williams turned in the saddle and pointed. ‘Bear right at that tree, follow the wall of the orchard and then cross the stream and form in column at quarter-distance on the slope beyond it. An orderly dragoon is waiting there to mark the spot.’ The only response was another nod. Williams was new to the brigade and not yet one of the family.

He nudged Francesca and set her trotting back past the column, before veering off up the side of the valley.

‘Goddamned dandies!’ Someone swore as he passed and he realised too late that he must have flicked mud up over the marching men. He regretted his lack of care and laughed at the thought of being dubbed a dandy. Any officer on a horse who was not from their own battalion was always treated with suspicion. Men might wonder what folly had been cooked up for them by the powers on high, but they would not wonder for long because there was nothing that they could do about it.

Williams reined in at the top of the slope and looked back, pulling down the tip of his hat as he squinted into the distance. The last of the four companies at the head of the brigade was just beneath him. About three furlongs beyond them was the dark mass of another, larger column. He wished he had his old telescope, but did not bother to fish out the cheap replacement from his saddlebags. He did not need to see the slightly greater detail this would offer. Everyone was where they should be and now he needed to report this to his commander.

Riding back the way he had come, Williams took care to pass the marching men at a safe distance. Even so he half heard a flurry of comments, and was pretty sure that he caught a cry of ‘Missed us this time, yer booger!’ in a North Country accent. A good officer knew when not to hear things. He could tell that the men were in good spirits, and guessed that they realised the march was almost over. They always seemed to know, even before the formal orders had reached their officers.

They would be happy at the prospect of halting, hoping for the chance to rest – veterans like these could make themselves comfortable very quickly. They might be called upon to fight, for the French were close, but that was something they could worry about if and when they were sent forward. At least the rain had stopped. Only a fool or a cavalryman wanted to fight when it was wet. Just a few drops of water seeping into the frizzen pan of a musket turned gunpowder into a dirty sludge no flint would spark into life. So the light infantrymen were glad it was dry – their very lives might well depend on it.

Tired, uncomfortable in their sodden greatcoats, these men were nonetheless indeed in good spirits, and Williams knew that the same enthusiasm spread throughout the entire army. For once, for the first time in years, they were advancing and the French were going back. At this rate there would soon be scarcely a French soldier left in Portugal, save for the prisoners crammed in the transport ships off Lisbon. Spain was another matter, but at long last the inexorable advance of Napoleon’s legions seemed to have slowed and then stopped. They were retreating for a change, and Williams had enough grim memories of the long retreat to Corunna to know how rapidly confidence faded into despair, and just how easily an army of brave soldiers could fall apart.

Five minutes later the grey mare cantered up the last slope and Williams joined two other officers sitting on horseback overlooking the wide plain.

‘The Light Companies are up, sir,’ he reported. ‘The Sixty-sixth are half an hour’s march away and the guns just behind them.’

Lieutenant Colonel Colborne nodded. He was a slim, handsome man in his early thirties. At six foot he was just a little shorter than Williams and in many ways he was a slighter version of the Welshman, his darkly fair hair flecked with grey.

‘Look, sir, they are moving.’ Captain Dunbar was pointing at the French column formed little more than half a mile away on the old highway running east towards the Spanish border. Beyond it was Campo Major, its medieval walls showing the scars of cannon strikes. Its defences were old, in poor repair, and not designed to deal with the assault of a modern army, and yet an elderly Portuguese officer and a garrison of volunteers had held it for a week before being forced to surrender. ‘They deserved a better fate,’ Colborne had said, but no aid could reach here until several days too late. Now three divisions of infantry and a strong force of cavalry had come to take the place back, less than a week after its fall.

‘Perhaps seven or eight hundred horse and two or three battalions of foot,’ Dunbar said, ‘so two thousand all told?’ The French were formed with cavalry in the lead, then a darker, denser mass of infantry, and more cavalry bringing up the rear.

The colonel nodded. ‘That is my estimate.’

‘Cannot blame them for not wanting to make a fight of it in that old ruin,’ Dunbar added.

When they had all arrived, the British and Portuguese would number more than eighteen thousand men, and so the French column was lost, but only if enough of the Allies arrived in time. For the moment they could almost match the enemy numbers, but not with a balanced force. Williams saw the colonel lower his glass and glance at the two regiments of redcoated heavy dragoons formed up to their left. Beyond them, almost a mile away, there was a dark smear moving slowly over the rolling ground, following the path of a little river. The colonel did not need to use his telescope to know that these were the British light dragoons and the Portuguese cavalry – everyone said that Colborne had the best eyesight in the army.

Until last summer the lieutenant colonel had commanded only the second battalion of his own regiment, the 66th Foot, one of four battalions in the brigade. Then the divisional commander had moved to higher things, and their brigade commander had in turn moved up to lead the whole division. Colborne’s rank as lieutenant colonel had been gazetted before that of the men leading the other three battalions, so overnight he had jumped to lead the brigade. The post was not permanent, but in the last seven months no general had appeared from Britain to take over. A few days ago Williams had arrived to replace his aide-de-camp, who had got his step to major and gone back to his own corps. The Welshman was now acting ADC to an acting brigade commander and had no idea how long this would last.

In the meantime Colborne kept his two staff officers busy. Dunbar as brigade major was given the greater responsibilities, but often both men found themselves trailing along behind the colonel, who slept little and employed every hour of the day to the fullest extent.

‘We must do everything within our power, Mr Williams,’ the colonel had told him when he first arrived, ‘and not spare ourselves if a little more effort helps to ensure victory and spare the lives or preserve the health of our men.’

It was Colborne who had led the others on the reconnaissance to find the route the main column would follow, looking for the easiest path, but also the one offering best protection from prying eyes. They had not seen a single French outpost, but then that was no surprise. The French kept their patrols and sentries close for fear of the vengeance of local peasants on any man caught on his own. They tended to stay especially close when the weather was so foul.

While the stormy night had lasted the lieutenant colonel led the vanguard of the army, with his own brigade and some attached Portuguese cavalry. When dawn broke – even the grey dawn of a gloomy day like this – that responsibility passed to the commander of the Allied cavalry, although he was now under the eye of Marshal Beresford, who had come up with his staff. The marshal was in charge of this southern force detached from the main army under Lord Wellington. Regardless of rank, it was clear that Lieutenant Colonel Colborne remained eager to spur his seniors into swift action, before the French column escaped.

‘Captain Dunbar, ride to Marshal Beresford and inform him that the First Brigade has arrived, and that I hope to have Major Cleeves’ brigade of guns up soon.’

The brigade major nodded and set off at a canter. Williams noticed that he had changed to another horse from the one he had ridden during the night. An ADC could not perform his duties without at least two good mounts, but he doubted that the chestnut would recover for a week or more and might well prove prone to the same failing in the future. Williams suspected that he was a poor judge – certainly an unskilled buyer – of horseflesh and had been fleeced. Up here near the frontier there was little chance of finding another mount for sale. That left one obvious source, and it was clear that the colonel’s thoughts ran along a similar line.

‘Mr Williams, ride to Brigadier General Long and his cavalry and tell him that the infantry are up so he may press as hard as he likes. There is no reason for a single Frenchman to escape.’

‘Sir.’

‘And, Mr Williams, I do not require you back for a little while, but take care, for it would inconvenience me if you did not return at all.’ Colborne’s eyes sparkled.

Williams grinned, and set the grey off at a trot to preserve her strength. The British army was advancing, its spirits were high, and he was going to steal a horse from the French.

‘Bills! Bills, you old rogue!’

Williams had hoped to pass Marshal Beresford and his staff without attracting attention. Then annoyance turned to pleasure when he recognised Hanley riding over to him and waving his hand in greeting. They were both officers in the 106th Foot, and had served together in its Grenadier Company when the army first came to Portugal.

‘I did not know you were here,’ Williams said after they had shaken hands.

‘Ever elusive,’ his friend replied, ‘flitting from shadow to shadow.’ Once an artist, then only with great reluctance a soldier, Captain Hanley was now one of the army’s exploring officers, riding behind the French lines – at times more the spy than became any gentleman. A few weeks ago Williams had sailed up from Cadiz with him, but the two had gone their separate ways after Lisbon.

‘Any news of Billy and the others?’

‘Yes,’ Hanley answered. ‘The battalion has come north and is to be attached to the Fourth Division. They may already have joined for all I know.’ Hanley had spent years in Madrid before the war, and with his black hair and tanned complexion readily passed as a native. ‘More than that I do not know. I fear my omniscience is waning!’

‘And the major?’ Hanley was an old friend, often a confidant, and no doubt guessed far more than he had ever been told, and yet even so it was difficult for Williams to broach so delicate a subject.

Hanley grinned, his teeth very white. ‘Major MacAndrews is well as far as I know, although still waiting for the promised brevet promotion to be gazetted.’ He paused for a moment. ‘And I believe it more than likely that his family will accompany him – to Lisbon at least, if not up to the frontier. You know the determination of Mrs MacAndrews.’ Major MacAndrews’ tall American wife was a formidable lady, held in awe and a good deal of affection by those around her, and she followed him to garrisons and on campaign alike. Only one of the couple’s children had survived to reach adulthood, and Williams was the devoted admirer of the girl – a secret shared only by the entire regiment. Jane MacAndrews was small, fiery of hair and character, and in his view the most perfect woman he had ever met. Just when he had dared to hope, it appeared that all must be over. Williams felt despair engulfing him again, something the constant activity of recent days had kept at bay.

‘Look, Bills, I really should not worry …’ Hanley began, only to be interrupted. A rotund civilian escorted by four hussars from the King’s German Legion had joined them.

‘Mr Williams, it is a pleasure to see you. I trust that you are enjoying your duties with Colonel Colborne?’ Mr Ezekiel Baynes was fat and red faced, the very image of the stout English yeoman beloved of cartoons. Before the war a trader in wines and spirits, he had become a master of spies for Lord Wellington. His voice was gruff, his speech rapid so the words tumbled out one after another like coals poured from a sack. ‘You are looking well, sir, indeed you are. I see that you are quite recovered from your wound. Splendid.’

‘Thank you, sir, I am pleased to say that it no longer troubles me.’ Williams had been shot in the hip back in the autumn, which had undoubtedly saved his life since it pitched him over and meant that a second bullet aimed at his head merely grazed him. Left behind by the army, he had spent weeks lost in fever and then even longer recovering, sheltered by a band of guerrilleros, partisan fighters who fought the bitter ‘little war’ against the French. Those months already had a dreamlike quality, and he knew that he had not yet made peace with himself for all that he had seen and done. As with so much else, not least the matter of Miss MacAndrews, there had not been time. It was typical of Baynes to parade his knowledge, while giving the impression that he knew much more than he said. Given the man’s rapid intelligence and his occupation, it was quite possible that he did.

It seemed that Hanley, Baynes and their escort were also seeking out General Long. ‘A happy chance,’ Baynes declared. ‘We shall be most glad of your company, and perhaps your assistance.’

Williams was very fond of Hanley, but had serious doubts about his judgement. His friend was a gambler to his core, a man who enjoyed cleverness for its own sake, his thrill growing with the size of the stakes, and so was all too ready to risk the lives of those around him in elaborate schemes to outwit the enemy. Baynes’ bluff and open manner veiled a sharp, ruthless mind, judging the benefit and price of every venture in the war with as calm a manner as he had once run his business. Together the two men were likely to prove dangerous company.

As they rode along, Williams confessed to his true errand, prompting a benevolent smile from Baynes and a snort of amusement from Hanley.

‘Pringle was right,’ his friend said, ‘you have turned pirate!’

The previous year Hanley, Billy Pringle and Williams had spent months in Andalusia working with the partisans along the coast, carried ashore and retrieved each time by the Navy. One night Williams had taken part in a cutting-out expedition, capturing privateers and merchantmen from an enemy harbour. As a result, he later found himself the surprised recipient of six hundred and twelve pounds, seventeen shillings and thruppence prize money, paid into his account at the regimental agents of Greenwood, Cox, and Company, agents to the 106th as they were to half the army. It was only this fortunate event which permitted him to accept the invitation to become a staff officer. More than half had gone on equipping himself for the field, since Lisbon prices were grossly inflated after four years of war and with the entire army wintering near the city.

‘It appears the simplest solution to my want,’ Williams said in his defence. ‘There is no prospect of purchasing a replacement for some time.’

Baynes chuckled, his face bright scarlet. ‘Clear, reasonable thought,’ he said. ‘The world is often so unfair when it dismisses the intellect of soldiers!’

Williams bowed as far as it was possible in the saddle.

‘Yet, though as a mere civilian I may be mistaken,’ Baynes continued, ‘is it not the rule that captured horses are to be offered for sale to the commissaries, so that the entire army and the wider cause may benefit from their capture?’

That was the rule, and although Hanley’s expression betrayed his lack of concern for such regulation, Williams had feared that this would prove an obstacle and so had hoped to avoid anyone too senior from finding out about the business. The justification that the rule was often ignored, and that a horse taken from the foe was the only plunder considered acceptable for an officer to take, seemed weak.

‘It is for the good of the service,’ he ventured, disliking the pomposity of his claim and hoping that the unmilitary Baynes would not pursue the issue.

‘I have no doubt of it, so perhaps we should leave it at that, and leave you, my young friend, with the more pressing problem of dividing an unwilling Frenchman from his horse. Of course,’ he went on, ‘though I am no real judge, I am told that our own cavalry officers ride finer horses than the French. Indeed, it is said their comrades garrisoned in France write to friends asking them to capture such a beast, with the promise of rich reward. Perhaps for the pure good of the service you should look elsewhere?’

Williams grinned, and a few moments later Baynes chuckled again to demonstrate that it was – almost certainly – a witticism.

‘I doubt in the circumstances that the Army will be much inclined to examine the details of your acquisition, since part of our purpose today is to arrange theft on a far grander scale. Damn the man, will he not sit still for a moment!’ This last was presumably directed at General Long and the light cavalry, who had set off forward again, just as they were coming up to them.

Hanley waved a hand at the corporal in charge of their escort to show that they would keep at a walk and not race forward to catch up.

‘Don’t want the horses tired,’ he explained to Williams.

‘Indeed not, indeed not,’ Baynes mumbled. ‘And no doubt they will halt again soon enough.’ He stared at Williams for a moment and then turned to Hanley. ‘Your friend is not the most curious of fellows, is he, William? We confess a conspiracy to rob and he says nothing. Too caught up with plotting his own act of brigandage, no doubt.’

‘It is for the good of the service,’ Captain William Hanley agreed.

‘Since manners or disinterest prevent you from asking,’ Baynes began, ‘I shall declare that our interest is with cannon – at least one of our interests. Does that stir your curiosity?’

‘The French siege train?’ Williams ventured.

Baynes turned back to Hanley and gave a nod of exaggerated approval. ‘Your Mr Williams may not be inclined towards curiosity, but at least his mind works quickly. Yes, Lieutenant,’ he continued, smiling now at Williams, ‘the enemy brought some fifteen or sixteen heavy guns to besiege Campo Major.’

‘They left just before dawn,’ Hanley added. ‘The Portuguese cavalry saw them. They must be three or four miles away by now. It would be better for us if they did not reach Badajoz.’ The big fortress town protected the Spanish side of the frontier.

Baynes’ face became serious for the first time. ‘It really is all about Badajoz. Are you familiar with the place?’

Williams nodded. He had seen the fortress back in ’09, when the army was forced to retreat even though it had beaten back the French attacks at Talavera. Those were bad times, with sickness rampant and claiming almost as many lives as the battle, and perhaps those bad memories shaped his recollections for to his mind there was something sinister about the place. Built in a naturally strong position, the King of Spain’s engineers had done a fine job, following the most modern principles of military science to fortify it. Its defences were as far removed from those of Campo Major as a rifled musket was from the flint-headed spear of some primitive tribe.

‘It is formidable,’ he said, trying not to think of the horror that would come when regiments were thrown against its walls. The French had had trouble taking the place, and it was only the death of its tough old commander and his replacement by a weaker man which had taken the heart out of the Spanish defenders.

‘The French have held the place for two weeks,’ Hanley said. ‘The longer they hold on to it then the more chance they have to repair the damage inflicted on the walls by their own guns. So our best chance is to attack soon, and for that we need a siege train.’

‘We do not possess such a thing.’ Baynes spread out his palms and then calmed his horse when the a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...