- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

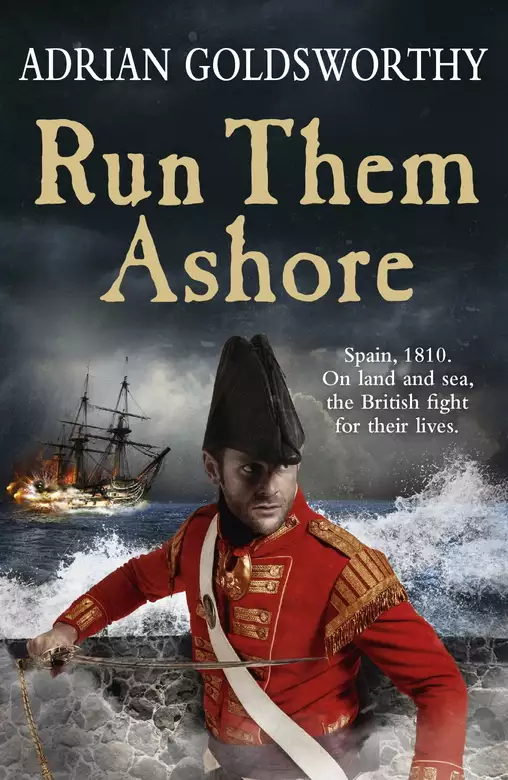

Synopsis

It's autumn 1810, Napoleon's legions have overrun Spain, and it looks as if Britain is losing the war. Backed by the Royal Navy, the British and their Spanish allies are clinging on to a toe-hold at Cadiz. As the French press ever closer, Lieutenant Williams of His Majesty's 106th Foot joins the Spanish partisans fighting behind enemy lines. Embroiled in the merciless guerrilla war, he soon realises that the greatest dangers come from his own side. A traitor is at work, and Williams must try to reach the British lines and warn them before a surprise raid on the French turns into a disaster.

Release date: August 14, 2014

Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Print pages: 428

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Run Them Ashore

Adrian Goldsworthy

There was the sound of scrabbling from behind and he did not need to look around to know that the others were catching up.

‘Oh, bugger me,’ sighed a faint voice amid laboured breathing. That was Sergeant Dobson, and it was reassuring that even the veteran was finding the climb heavy going. Although past forty, the sergeant had spent most of his life in the army and never seemed to tire, even on the longest of marches on the very worst of roads.

The breeze was picking up, rippling through the dry grass dotted all over the side of the dune, but if anything making the already close night even more stifling. It was a hot wind from the south-west – an African wind – and Williams had been told that after a storm it sometimes left a film of fine desert sand covering the rooftops and lanes here on the coast of Granada. Tonight it simply whistled along the little valley, stirring up the dust in swirls. Williams had no doubt that it was local Spanish sand that kept driving into his eyes, the tiny grains feeling like vast boulders.

That same sand also kept slipping underfoot as they climbed. Three steps upwards usually meant one or two sliding back down, and after a while they found it easier to progress crab-like, going along the dune as much as they went up it.

‘Leeway,’ muttered Williams to himself, and failed to stifle a laugh as the thought struck him that their progress was much like that of a ship. Repeated explanations, some in the last few days, informed him that the wind drove a sailing ship simultaneously forward and to the side, so that a vessel moved diagonally rather than straight. Williams still did not understand why, but was willing to accept it as one more mystery of God’s Creation.

‘Sir?’ hissed Dobson.

Williams looked back over his shoulder and saw the sergeant staring at him, face pale in the moonlight and the brass plate on the front of his shako gleaming. The veteran was using his musket like a staff to help him climb the slope, and Williams could not help wishing that he had done the same, instead of coming ashore with only his sword and a pistol.

‘Sorry, Dob,’ he said, and grinned. ‘I was away with the fairies for a moment,’ he added, using one of Sergeant Murphy’s favourite expressions. The Irishman was down in the valley with the main party, spared the long climb because he had barely recovered from a leg wound taken in the summer.

‘Ruddy officers.’

The sergeant’s words were almost lost as a fresh gust of wind hissed across the dunes, but he could see Dobson shaking his head. An officer now, Williams had joined the army more than three years ago as a Gentleman Volunteer, too poor to buy a commission and without the connections to be granted one. Dobson had been his front rank man when Williams carried a musket and did the duties of an ordinary soldier, all the time living with the officers of the regiment and hoping to win promotion by performing some foolhardy act of valour and surviving to be rewarded. In spite of their differences – Williams was a shy, religious and somewhat earnest young man with a romantic view of life and honour, whereas the hard-drinking Dobson had been broken back to the ranks several times after going on sprees – the two men had taken to each other.

‘You’re my rear rank man, Pug,’ the veteran had said, his hands on Williams’ shoulders, and using the nickname the volunteer had picked up. ‘If it comes to a fight then we keep each other alive, so I need you to know what you’re at and not shoot me by mistake.’ In the company formation the pair stood one behind the other and if they extended into loose order then they worked as a team.

‘And if you must become a bloody officer,’ he had added, his weather-beaten face serious, but his eyes twinkling with amusement, ‘then you had better be a bloody good one, or you’ll only get all of us bloody killed.’ Williams had found himself returning Dobson’s broad grin, and felt that he had truly joined the ranks of the Grenadier Company.

The veteran had taught him a lot about soldiering, and in more than three years of hard service in Portugal and Spain the two men had only grown closer. Williams had been commissioned after Vimeiro and the veteran had helped him win confidence as an officer. At the same time Dobson appeared a reformed character, no longing drinking and raised to sergeant once again. Such a remarkable change seemed entirely due to his new wife, the prim widow of another sergeant who had died on the grim road to Corunna, not long after Dobson’s wife had been killed in an accident. It was an unlikely match, and yet clearly worked well for them both and for the wider good of the regiment, which thus gained a highly experienced and steady NCO.

Williams saw Dobson speak again, but lost the words in the sighing of the wind.

‘Are we going, then?’ the sergeant repeated more loudly, just as the breeze dropped away so that he seemed almost to be shouting.

Instinctively they dropped to the ground, the sailor behind Dobson a little slower than the two soldiers. Williams felt himself slipping down the slope and so grabbed two handfuls of grass and clung on. They waited, listening, hearing nothing save the gentle whisper of the wind, the still fainter sigh of the surf on the beach, and then, louder than both, the unnatural rattles, bumps and muffled curses as the main party carried their heavy loads up the track at the bottom of the valley.

Williams looked up, but could not see past the crest. He did not sense any danger, did not feel the slightest trace of that discomfort, nearly a physical itch all over his skin, that came so often when an unseen enemy was near. Dobson had long ago taught him to trust his instincts as much as his head, and always to suspect a threat even when one should not be there. ‘Never trust any bugger who tells you it’s safe,’ had been the precise words, but now he sensed that even the veteran was relaxed. Williams wondered whether a fortnight on board ship had taken the sharp edge off their instincts, just as it seemed to have softened their muscles so that climbing this slope left them spent.

It took a concerted effort for Williams to keep reminding himself that they were in Spain, away from the main armies, it was true, but still in a region overrun by the French invaders since the start of the year. All Andalusia was now in the hands of Bonaparte’s men, and his brother Joseph, puppet king of Spain, had been welcomed by cheering crowds when he toured the southern cities some months ago. As 1810 came to a close, there was not much of the country the enemy did not hold, and Massena’s invasion force was also deep inside Portugal, as Lord Wellington retired closer and closer to Lisbon. Williams had seen some of the fortifications built along the heights of Torres Vedras to halt the French. They had looked strong, but so many people were convinced that the war was lost that it took a good deal of stubborn faith to believe that the invaders would be stopped.

This was enemy territory, and although bands of guerrilleros still resisted, most of them were in the hills and mountains further inland where it was easier to evade French patrols than here in the open country near the coast. Andalusia was big, and Napoleon’s soldiers spread thinly as they struggled to control all the many towns and villages. There was no French garrison of any size for more than ten miles, and the few outposts too small for the soldiers to risk leaving their shelter at night when the partisans were most likely to roam. The beach below them was a good place to land, but then so were most of the beaches along this coast. There was simply no reason for enemy soldiers to be at this out-of-the-way spot on this night, and thus there should be no danger. Perhaps that was why Williams kept telling himself that he ought to be worried.

‘Come on, then,’ he said, gripping the clumps of grass and half pulling, half pushing with his feet to clamber up the last few yards of slope. His mind conjured up images of a line of French soldiers waiting just over the crest, bayonets sharp and muskets primed and loaded, having watched with amusement as the damned fool redcoats toiled up the side of the dune. He tapped the butt of the pistol thrust into his sash to check that it was still there, but needed both hands to climb the last four or five feet, which were almost vertical.

Williams eased his head over the top. Eyes gleamed as startled faces watched him, and then the pair of coneys bounded off through the grass. Otherwise the ridge was open and empty, stretching for ten yards or so before gently sloping down again. He pulled himself over and knelt to look around. The grass was thicker up here and the ground more solid underfoot. Ahead it dipped down a little towards the road, the bright moonlight showing that this stretch was paved and well maintained. On the far side the land rose again, and a few miles away he could see it climbing steeply towards the mountains of the Sierra de Ronda, darker shapes in the general blackness beyond. To his left the road wound down through several little valleys as it went further inland, but still followed the general shape of the shore. He could see it as a lighter thread running steadily on over the plains a good mile away. Williams looked to the right and could not see so far because the land rose a little before falling sharply back down towards the sea. Yet it was as they had expected, a neat round knoll on the far side of the road at the top of the valley they had climbed, and perched on its crest was the tower of a little church. It was all just as they had been told.

Dobson scrambled over the edge and knelt beside him. He was still breathing hard, but immediately brought up his musket, brushing sand from its mechanism and checking that the powder had not shaken out from the pan. A grunt of satisfaction showed that all was in order, and there was a loud click as he drew back the hammer to cock it. Prompted, Williams pulled the pistol from his sash.

‘Looks clear,’ he whispered.

‘Aye,’ Dobson replied.

The sailor came up to join them, but when he began to stand the sergeant reached up and gestured for him to crouch. There was no sense in offering too high a silhouette, just in case the land was less empty than it seemed.

‘There’s the old church,’ Williams said, and pointed.

‘God bless the Navy for landing us in the right place,’ muttered Dobson, and winked at the young topman who had accompanied them. The lad unslung his musket. His movements were looser, less formal than those of a soldier or a marine, but he looked as if he knew how to handle the firelock. Thomas Clegg was rated Able Seaman and was seen as trustworthy by his officers, otherwise he would not have been included in this landing party, let alone chosen for this detached duty when there were bound to be plenty of opportunities to run off into the darkness.

‘Cannot see the signal, though,’ Williams added. The sign was to be a lantern shining from one of the windows in the tower, showing that the guides were waiting with the mules needed to carry the muskets, cartridges and other supplies brought by the main party. All were destined for the serranos, the partisans fighting in the mountains, but to reach these elusive bands of patriots the British needed to be shown the way. Waiting with the guides was supposed to be a Major Sinclair, the man who had requested this aid.

Williams did not know much about the major, except that he had been on his own helping the guerrilleros for a long time. There were quite a few officers like that around, especially here in the south, some sent from Gibraltar, others from Cadiz, and still more from Sicily or any of the other Mediterranean Islands in Britain’s hands. Many had a reputation for being unorthodox, and the little Williams had learned did not inspire a great deal of confidence in Sinclair. His friend Billy Pringle had gloomily told him that the major was not from a line regiment, but held rank in some ‘tag, rag and bobtail corps’ recruited from German, Italian and even French deserters from Napoleon’s legions.

Captain Pringle commanded the Grenadier Company of the 106th Foot, in which Williams, Dobson and Murphy all served, and he was also at least nominally in charge of this mission to aid the serranos. In truth Pringle would be guided by Hanley, another friend and yet another grenadier. No, that was no longer true, thought Williams, for just a few weeks ago Lieutenant Hanley was gazetted as captain, and so would be transferred to command one of the other companies. His elevation left Williams as the only lieutenant in their little group of friends, but seemed to mean little to Hanley, whose three years as a soldier had scarcely altered his lack of interest in rank or the other formalities of military discipline.

‘They’re nearly at the top, sir,’ whispered Dobson, his burring West Country accent still strong after a lifetime with the army.

Williams looked back and saw that the main party was coming to the head of the valley. The shapes of the sailors carrying their heavy burdens were vague, but the marines marching in front of them were clearer, their white cross-belts marking them out. He could not see either Pringle or Hanley distinctly, but guessed that they would be a little way in advance, looking for signs of their guides.

The wind freshened again and his nostrils filled with that salt smell, subtly different and yet still so clearly akin to the one he had known while growing up beside the Bristol Channel that it took him back to his childhood. That was surely another reason why he felt so safe when he should really be wary and alert. As he looked out to sea, the not quite full moon was bright in the sky, with a long reflection on the water outlining His Majesty’s Ship Sparrowhawk and its two masts so perfectly that it looked like a painting. It was a peaceful, even beautiful, scene, and he was tempted to sit and simply stare out from the hilltop because it was so lovely.

‘Look, sir, the light.’ Dobson sounded relieved, and Williams had to admit that everything was going smoothly. Soon they would go down to join the main party, and then he and the other soldiers would take the supplies inland to the serranos while the sailors and marines rowed back to their ship. The redcoats were to spend a week with the Spanish, before going to another beach to be picked up by the Navy. It all seemed very simple.

Yet Williams did not trust it. Hanley was a splendid fellow in many ways, witty, educated and travelled – all things Williams admired because his own education had been severely limited by his family’s straitened circumstances. His friend was very clever, and his sharp mind and fluency in Spanish more often than not took him away from the regiment and sent him off to gather information about the enemy. Much of the time Hanley was deep in French-held territory and he did not always wear uniform. Williams hesitated to employ so unbecoming and dishonourable a word as spy, but knew that that was the truth of it.

Hanley revelled in outwitting the enemy and often showed a ruthless streak in his willingness to gamble with the lives of others as if the higher the stakes the more satisfying the game. Williams sometimes doubted his friend’s judgement, and had even less faith in the men who gave Hanley his orders, sure that they would have no qualms about sending them all to their deaths for the sake of some grand deception. They were clearly behind all this, plucking them all away when they were travelling back to join the battalion and sending them off to make contact with the guerrilleros. Before that they had all formed part of a training mission attached to the Spanish armies further north, and that posting had seen them stranded inside the besieged town of Ciudad Rodrigo as a token gesture made by the British to their allies. They had helped Hanley hunt an enemy spy and then been hunted in turn by a determined and ruthless French officer. Only through sheer luck had they managed to escape, and now they were once again dispatched into enemy-held country.

Williams suspected that there was far more behind their current orders than first met the eye. Sparrowhawk’s captain was one of Billy Pringle’s older brothers, and what should have been a happy coincidence only made him more suspicious that this was no chance, but an element of some subtle scheme which he could not yet discern. Williams hoped and prayed that understanding would not come at too high a price, and felt himself being drawn ever further into the murky world in which Hanley took such evident delight. Still, at the moment it all seemed to be progressing most satisfactorily.

‘Something moving, sir! Mile away to larboard!’ Clegg had not quite shouted, but his report was given with a power no doubt intended to carry over the noise of weather and a working ship.

Williams saw that the young sailor was pointing to the left, down along the coast road. He stared, but could see nothing, and so pulled his cocked hat down more tightly and held it there in the hope of shading his eyes from the moon.

‘Can you see what it is?’ he asked.

‘No, sir. Just a shade at this distance.’

There was something, but Williams was staring so hard that he blinked and lost it. He scanned the thread-like line of the road and saw nothing.

‘See anything, Dob?’

‘No, but my eyes aren’t what they used to be.’

‘It’s there, sir,’ Clegg repeated in a tone of mild offence. ‘On the road.’ The lad gestured again.

‘If you would be kind enough to get my glass, Sergeant.’ Williams carried his long telescope strapped to the side of his backpack and it was easier for Dobson to slide it out than for him to reach it. Then it did not matter because he saw it. The moonlight glinted on something metal and then there was an obvious dark patch moving along the road. It was coming towards them.

‘You have fine eyesight, Clegg, fine eyesight indeed.’

Now that he had spotted the movement, Williams found it easy to trace, and so waited before using his glass in the hope of seeing more detail.

‘Horsemen, sir?’ suggested the sailor.

‘I believe so. From the speed if nothing else, and coming this way.’

‘Ours or theirs?’ asked Dobson, although his tone contained little doubt that they were enemy. ‘Though I can’t say I can see them yet.’

‘Must be French,’ Williams said. ‘And there is no reason for them to stop, so if they keep coming they will be here in fifteen or twenty minutes and if we can see them at this distance they must be in some strength.

‘Well then,’ he continued, trying to think clearly as the ideas took shape in his mind. ‘Dob, I need you to go back to Mr Pringle and tell him I need the marines up here. Suggest that he hastens loading the mules as much as possible and then pushes on with them. Ask Mr Cassidy to take the Sparrowhawks back down to the beach and to wait for the marines there.’ Cassidy was acting lieutenant on the brig and in charge of the landing party. ‘Got all that?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Dobson replied formally, and stood up. ‘You should go, though, and I’ll stay.’

Williams smiled. ‘They will obey you. If I go we will only have a discussion.’ He was junior to all the others, but was more worried because he did not know what sort of man Sinclair was.

‘Aye, you may be right, Pug.’

‘When you come back,’ Williams continued, ‘split the marines into two parties. Leave Corporal Milne with one lot here and take the other half up to that rise.’ Williams showed where he meant. ‘Clegg and I will take a look further down.’ He patted the sailor on the shoulder. ‘I need those eyes of yours.

‘We’ll try to remain out of sight, but we will distract them if they are coming on too fast. You wait, and give them a volley when they get close. They’ll only be expecting irregulars so will probably charge straight at you, so after that one shot take the men down the side of the dunes to the boats. If I don’t see you I will be back here with Milne and we will give them another surprise before we bolt down to join you.’ A thought struck him. ‘You had better give Mr Pringle our apologies and say that we are unlikely to be joining them and so they must proceed without us, so tell them not to wait around, but press on. We can maybe give them half an hour’s lead and that will have to be enough.’

Dobson nodded.

‘Good luck, Dob,’ Williams added, and watched the sergeant jog down on to the road and head towards the chapel. ‘Come on, young Clegg, let us go and make some mischief.’

Williams ran along the top of the ridge as fast as the tussocks of grass allowed. He had his pistol in his right hand and the heavy telescope in the other. The straps on his pack had worked loose again, so it banged against his back as he ran, but although the night was no cooler and the wind stronger than ever the officer no longer noticed it. Tiredness had gone along with the uncertainty and that strange sense of peace, for now he knew what he had to do. That did not mean that it would be easy to do it.

He stopped on the rise where Dobson was to bring his men, lay down and propped his glass between two rocks.

‘There they are, sir,’ Clegg said, spotting them several moments before the officer.

Williams pressed his eye to the lens and tried to move the telescope as gently as possible while he hunted for the enemy. It was a shame he did not have one of the night glasses he had seen on board the brig, but the moon was still strong and he soon found them. They were certainly cavalry, and were moving quicker than he had judged, so that when he pulled away from the glass to gauge the distance he guessed that they were now barely half a mile away. The French – they must be French for they were moving in better order than any partisans – were coming on at a steady trot, which suggested a clear purpose, whether or not it had anything to do with them. It was hard to know whether the enemy would be able to see the Sparrowhawk off-shore, but they certainly would by the time the road climbed up on to this ridge. Numbers were hard to determine in the darkness, but he doubted it was less than a company and probably a full squadron of more than a hundred riders.

‘Come on.’ Williams set off down the slope as the ground dipped into another little valley and then rose sharply to a round hillock, the highest point on the dunes. From the top Williams could see the road curving around its foot and then running in the gentlest of meanders down towards the coast. There was nowhere more promising down there, and so this was where they would wait, trusting to the steep sides of the hill to delay any mounted pursuit.

The officer pointed back towards the rise they had come from. ‘Keep an eye out, Clegg, and tell me when Sergeant Dobson and the marines arrive.’

They waited, and it was hard to know how much time was passing. Williams promised himself once again that as soon as he had the money he would purchase a good watch, although even that would do nothing to hurry the sergeant along and perhaps it would only make him nervous to see the hands moving. He shook off his pack and strapped the telescope in place before slipping it back on. It was awkward, but they were going to have to move in a hurry and he did not want to risk losing it. Then he checked his pistol, flicking open the pan and feeling the priming. There was very little left and he was afraid some of the grains he touched would be sand instead of powder.

‘May I trouble you for the loan of a cartridge,’ he said.

Clegg looked surprised. ‘Aye, aye, sir,’ he responded through habit, and fished into his pouch to hand one over.

Williams bit off the end, spitting out the ball, which would be too large for the barrel even if his pistol was unloaded, and sprinkled some of the loose powder into the pan before closing it. Following his example, the sailor made sure of his firelock.

There was no sign of Dobson, and the French were getting closer. Now and again the wind carried the sounds of hoofbeats on the road and the bump and rattle of men and equipment. They waited, and still the rise behind and a little below them was empty. The cavalry came on, individual horsemen distinct now from the darker mass. The next strong gust carried with it a hint of old leather and horse sweat.

The French were close, the advance piquet of four riders no more than three hundred yards away, turning the bend which led towards the hillock. Williams glanced back. The rise remained bare and he wondered whether his message had been ignored or overruled. It was too late now, and so he must try to gain any time he could.

‘Clegg,’ he whispered. ‘We will take a shot at the French in the hope of confusing them and slowing them down. I want you to wait until I fire before you pull the trigger. After that, we both run like rabbits. Keep to the slopes of the dunes.’ Williams hoped that the sand would be too soft for the horses to follow. ‘You understand?’

The sailor nodded. He was pale, but that could easily have been just the moonlight, and he looked to be a steady fellow.

Williams pulled the hammer of his pistol back to cock it and Clegg did the same. The French were close now, and he was surprised that they kept at a trot and simply rode along, apparently unconcerned that the road went between hills and offered so many good places for an ambush. Perhaps they did not expect any trouble from the serranos so close to the sea, and then Williams wondered whether the cavalry simply preferred to rush through ground where it was difficult for them to fight. If that was so, then he might be doing precisely the wrong thing and would only force them to hurry even faster towards his friends. Doubting his judgement and not knowing whether or not the marines were coming to support him, Williams considered whether it was better simply to slip away and hope that the main party had got clear.

The piquet kept coming, little more than a hundred yards away and the main body a musket shot beyond that. If they kept at this pace then they would still probably catch the others, and so he had to try the only thing that might stop them. Williams decided and closed his eyes.

‘Now!’ he said, and pulled the trigger. It was an absurd range for a pistol at any time, let alone in the dark, but he still saw the burst of flame as a yellow blur through his eyelids and then Clegg’s musket went off with a deeper boom and an even bigger flare. ‘Run!’ he shouted, without bothering to see whether either shot had struck home. There were shouts from the road, and the crack of carbines as the piquet replied.

The two men sprang up and fled, running as best they could through the thick clumps of grass and then skidding, almost falling, down the soft sand of the slope. There were more shouts and the sound of hoofs pounding on the paving stones. Another carbine fired and Williams heard the ball snap through the air only a foot or so over his head.

‘Come on,’ he called, swerving to run along the side of the ridge. The barefoot Clegg took no urging and sped ahead of him, his shoeless feet gripping better than the smooth leather soles of the officer’s boots. Williams felt himself slipping, and his left side dropped down on to the ground. He was sliding, rolling on to his back, until one foot hit a rock and, dropping his pistol, he managed to take hold of some grass. Looking back he saw several French horsemen on the road at the top of the little ravine. The night was shattered by another sharp crack as a carbine flared, and a ball twitched the grass he was holding. Williams instinctively let go and started sliding again, free of the rock until one boot caught in a loop of grass and held him. He struggled free and managed to get to his knees.

One of the cavalrymen was walking his horse into the mouth of the little ravine. The others were behind, loading their carbines. Beyond them a clatter of hoofs announced the arrival of the head of the column. Someone was shouting orders in a clear voice.

Williams pushed himself up and managed to stand, right leg half bent to balance on the slope. The horseman was coming closer, calming his horse when one of its feet slipped for a moment. He was a hussar with his round-topped shako at a jaunty angle, and his fur-lined pelisse draped over his left shoulder. The man had clipped his carbine back on his belt and now drew his curved sabre, the blade glinting in the moonlight.

‘Hey, coquin,’ he said, urging his horse on. The animal slipped a little, dropping one shoulder, but again the hussar calmed it and came on.

Williams drew his sword and took guard, nearly losing his own balance before he recovered. The Frenchman stopped fo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...