Come with me into the shadows of night.

Keep to my paths, for the light will fade,

and I give no protection,

only dark fingers to guide you,

into my shadows in the bleak, black night.

The Waerg Woods Warning

Anon.

Chapter One – The Craft-Born Lie

When you live on the edge of a cursed forest, you do a lot of staring into the dark. The Waerg Woods is the kind of place travellers go hours out of their way to avoid. Yet somehow they still find themselves lost, seized by the bony fingers of roots, vines, and branches.

The magic of the realm died, and now only shadows remain. Shadows of the once enchanted forest where trees came alive and butterflies spread their sparkle through the air. Now they wait—what else can shadows do?—for magic to return.

I’ve read books about the magic dying. Wars ravaged Aegunlund hundreds of years ago, killing the magical Ancient Ones and smothering their powers. But every now and then one person is born with the old craft, and it reignites the magic in the entire realm.

Father points to the ground. “See how the birch enriches the soil? It helps the bluebells grow.”

We stand in the Waerg Woods, searching for lumber. Each day we creep in a little farther, too frightened to chop down the trees, but in desperate need for anything to trade at the markets. The other villagers already think us stupid, crazy, evil, or any combination of the three, for entering the dark forest. We’re the last in our village who dare to venture in. Yet still they trade for our goods. Halts-Walden needs wood. Trees in the nearby fields are few and far between.

“We’ll take the lowest branches,” he says. “But no more.”

“If we take more, we can trade for cloth,” I argue.

He shakes his head. “No more.”

“Fine,” I say with a sigh.

I shimmy up the narrow trunk with a knife tucked into the sheath on my belt. I pull myself onto a low branch. It dips under my weight, and I remain positioned near the trunk. The fragrant air—full of earth, dust, and mildew—drifts to my nostrils. Sweet scents of nearby honeysuckle carry on an undertone.

“Careful, Mae,” Father warns. “Birch branches are thin.”

“I’ve been climbing trees since I could walk,” I snap. But still I lean against the trunk for support as I rub the serrated knife against the branch above. Father waits below for it to drop. He leans on his good leg, propping himself up with the cane we made from a fallen ash. His knee twisted in a fall from far up an oak, and ever since he’s needed the cane.

“Hoahh!” I call out as the branch creaks. I give it a final push away from me so that it doesn’t catch me on its descent. Anta snorts and jumps back. The branch lands a few feet from Father, and he leans low to drag it towards the small cart behind Anta. When he’s done, I move on to the next branch.

“That’s good, Mae. We can get good coin for this wood. And after the market, you must study.”

I roll my eyes. Father is obsessed with me book learning. He insists it will better me. Although I don’t see what it will better me for, seeing as he has no intention of ever letting me leave Halts-Walden, and it’s not like it got him anywhere.

As I start to climb down the tree, a humming noise attracts my attention from high up in the branches. A lone bee buzzes down towards me.

“Well, hello there,” I whisper to the bee, which orbits my head so fast my eyes can’t keep up. “I bet you have lots of lovely honey up there.” The nest might be within climbing range. It could be dangerous, but the thought of sweet honey is too tempting to ignore.

Tucking the knife back in my sheath, I reach up to the next branch and grip the trunk with my toes, worming my way up the birch.

“Mae? What are you doing?” Father calls from below. “We have enough wood for market.”

“There’s a hive of honeybees.” My voice comes out breathless as I climb. Beads of sweat begin to form on my forehead.

The grass rustles below, and I don’t need to look down to know Father has shuffled towards the tree. When he calls up, his voice is louder.

“Get down now. It’s too high. You could hurt yourself, or—”

“I’m fine.”

“Mae,” he pleads.

Normally, that tone would make me listen. When he uses it, I know he is thinking of Mother, and I know he worries he’ll lose me too. But today I want to reach that hive. I want to achieve something, to sense danger, to feel exhilaration. The higher I go, the more I feel like I’m finally escaping Halts-Walden, the sleepy village I’ve lived in for all of my life. My muscles sing out in pain as I hold my own weight, and the silvery bark scrapes against my rough hands, but I don’t care because I’m making my own decisions now.

I’m not afraid of bees. They’ll leave me alone. Bugs, bees, any kind of critter… I’ve never had a single bite or sting my entire life.

“That’s too high, Mae! Please. You could fall.”

I glance down and immediately regret it. I’ve climbed higher than I intended, and certainly higher than I’ve ever climbed before. The drop makes my head spin, and with a gasp I cling onto the tree, my fingers scraping the bark. Bees buzz around me, and the hive is just a fraction farther. If I climb down now, Father will have won. He’ll think he can guilt-trip me for the rest of my life, make me stay in Halts-Walden forever. So I grit my teeth and take another step up, my arms shaking with the strain.

When I’m close to the hive, I take some of the rope from my satchel and tie myself around the trunk. I gently ease my weight against the rope, making sure it holds me, then I take out a small tin box covered in holes. I don’t always carry this with me, but luck would have it that I decided to pack it just in case. Also in my bag is a flint, which I use to light the pine needles stored inside the tin box. After replacing the lid from the box, I place it on a branch near to the hive, letting the smoke unsettle the bees. They withdraw to the back of the nest so I can cut away at the honeycomb. With a sigh of relief, I pack up the honeycomb and put out the fire in the tin box.

I’ve done it. The risk paid off. Now we will have honey as well as wood.

“I’m coming back down,” I call to Father.

“About time,” he grumbles.

My fingers tremble as I loosen the knots in the rope. In my haste, I’d tied them too tight, and now I have to force them apart with weakened arms, digging my fingernails into the thick rope. With one huge wrench I pull the knot open, but it happens too fast. I haven’t gripped onto the trunk properly, and it knocks me off balance. I slide down the tree, desperately trying to dig my fingernails into the bark, but not finding purchase. As I begin to free fall, a scream escapes my lips and as I crash through branches, Father’s shouts become a muffle.

With my heart hammering against my chest, I stretch out my hands, stretching my fingers as far as they’ll go, trying to grasp hold of anything. One thin branch snaps as soon as I wrap my fingers around it. But it slows down my fall, allowing me to hook an arm over a larger branch, my body painfully colliding with it.

“Mae?” Father shouts in a panicked voice.

“I’m all right.” I pull myself back onto the branch, trembling from head to toe. My fingernails are broken, and two are bleeding. There are splinters in my palms that I have to deal with before trying to climb again. “I’m on a branch. I’ll be down in a moment.” A glance down shows that I fell far and I’m lucky. If I hadn’t caught the branch, I may have plummeted to my death. I take deep breaths, leaning back against the bark of the tree, slowly calming my heart.

After composing myself, I make a steady descent. Without a doubt that was the closest I’ve ever come to seriously hurting myself. It frightened me to my very core. Yet I cannot help feeling a sense of complete exhilaration. When my feet touch the grassy ground, all I can think about is how I want to do it again.

*

Later that day we make our way to the village market so we can trade some of the wood for milk and meat.

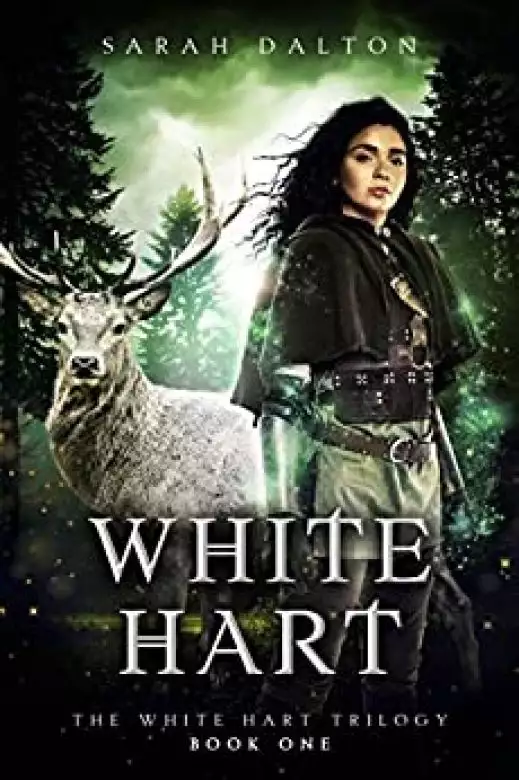

Back on the path, we pass those on their way to the nearby farms. Most villagers stay at an arm’s length from us. It could be the smell, or the fact we’ve come from the Waerg Woods. It could be Anta, who scares some people with his size and antlers. Either way, I don’t care. I only need Father and Anta.

Our cart creaks along as we follow the path out of the woods. The old goat farmer turns his head and stares at us with his eyes travelling along Anta’s flank. His eyebrows bunch together, as though he’s wondering why the white stag still stays with me. You’d think they’d be used to it, but Anta still turns heads.

Halts-Walden is different from the rest of the kingdom, or so Father tells me. I’ve never left my village. Settlers gathered here during the Realm War, sick to the stomach of violence. They wanted a peaceful life. Father and I are not the only dark-skinned people in our village—the immigrants came from all over Agenlund to Halts-Walden during the Realm War, including those beyond the Anadi Sands—but we are the poorest. Unlike other people from the Haedalands and the Southern Archipelagos, who came with riches from the diamond mines or the iron forges, my great-grandparents came with nothing. They spent many decades scavenging for timber to trade. They built a hut from their wares, and that’s where we live now.

Settled in the valley between the Red Peak Mountains in the south, and the Waerg Woods which stretch northwards towards Cyne, Halts-Walden is a self-contained village. With a small mill over the river, and a couple of farms on the outskirts, we survive without much contact from the rest of Aegunlund.

We pass the farms and head deeper into the village, where the market is set up in the courtyard outside the Fallen Oak tavern. People bustle around, carrying armfuls of flowers or baskets filled with baked goods. The scent of fresh bread makes my mouth water and my stomach growl.

“What’s going on?” I brush hair, dirt, and wood dust from my eyes, and address one of the milkmaids. She wears a long tunic, brought in at the waist with a rope belt. Her skirts bustle beneath the tunic. She weaves fresh flowers—bluebells, ivy, chamomile and rosemary, fragrant and sweet—through a wooden arch over the village gate. “Why are you arranging flowers?”

The milkmaid frowns at Anta before appraising my appearance with a raised eyebrow. “Been in the woods again, White Hart?” She tuts. “Robert, I thought you had better sense than to let your daughter roam around in that place.”

Father bristles next to me. “I need to feed her, don’t I?”

She mumbles something about getting a proper occupation years ago.

“The flowers,” I insist. “Are we expecting visitors?”

It seems I uttered the magic phrase, because her face lights up and her ruddy cheeks stretch with a broad grin. Her thin eyebrows raise high above her glistening eyes, moving swiftly with excitation. “The prince is coming for Ellen. It’s so romantic.”

Father and I share a glance. The king has been waiting for a craft-born to wed his son, Prince Casimir. They search far and wide for anyone who shows a sign of the craft—magic passed down through the blood of the Ancients—so they might restore magic to the realm and reignite the Red Palace. I know only rumours about the Red Palace, ones that speak of machines and contraptions that create light without a fire and make precious stones.

“Ellen is craft-born?” I ask. I know Ellen. She’s the miller’s daughter, and one of the prettiest girls in town, with milk-white skin, black hair, and oval-shaped blue eyes. When we were six, she pointed and laughed at the holes in my boots, so I pushed her into a puddle. Then I got a lashing from the miller.

The milkmaid nods so quickly her chins waggle. “Oh yes. She darkened ivy with a touch.”

I fold my arms and roll my eyes. Father sniggers. “Who told you that?” I say.

“No one needed to tell me anything,” the woman says. She bends low and snatches flowers from her basket. “The whole village knows it.” She turns her back on us and pushes daisies into her display.

We know the conversation is over and move Anta away from the woman.

Father elbows me lightly in the side. “Looks like you’re off the hook.”

I nod. “It does indeed.” I run a hand down Anta’s snowy coat. It sparkles with my touch, like icy snow or stars.

“Not in public, Mae. Even after the prince has married the girl, you’ll have to keep it a secret. You’ll never be safe otherwise.”

“I know,” I reply with a sigh, wrapping an arm over Anta’s withers.

They call me White Hart because on the day I was born—the day Mother died—the white stag appeared at the window of our hut, just a calf back then, so Father says. He tried to shoo it away, but the stag kept coming back, staring through the window, watching me as a baby. When I could talk, I yelled, Anta! Anta! I pointed at the large, furry antlers on his head, standing tall and crooked like the branches in the Waerg Woods.

No one knows why Anta stayed with me, or why he let me tame him. I ride him, too, and he drags the cart of wood to market. They whisper behind us, That’s no place for a white stag. What did they do to the creature? They have no right to own an animal like that... and more than once Father has had to threaten those who come to our house late at night, desperate to poach Anta for his fur. I’d never let anyone hurt him. I’d kill anyone who tries.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved