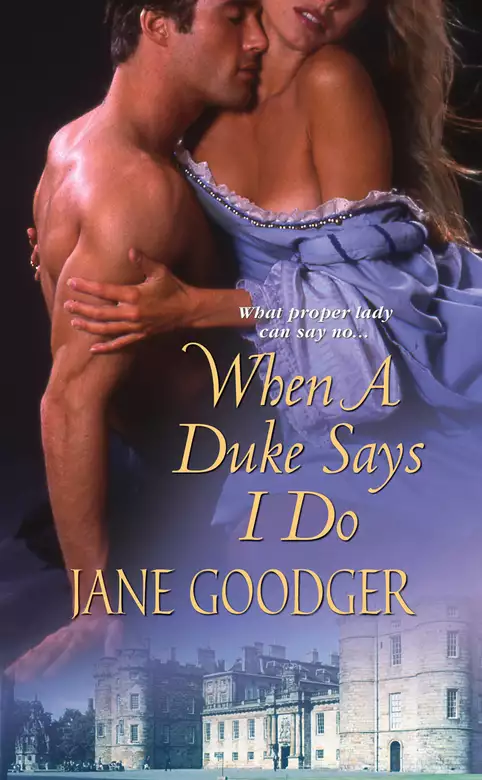

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Miss Elsie Stanhope resided in Nottinghamshire, an area so rich in titled gentlemen, so felicitous for marriage-minded mamas, it was called"the Dukeries." Indeed, Elsie had been betrothed since childhood to the heir of a dukedom. She had no expectation it would be a love match. Still less that she would enter into a shockingly scandalous affair with an altogether different sort of lover. And the very last thing she imagined was that the mysteries of his birth would be unraveled with as many unforeseen twists and turns as the deepest secrets of her heart. Praise for the novels of Jane Goodger "Gentle humor, witty banter, and attractive characters." -- Library Journal on Marry Christmas "A touching, compassionate, passion-filled romance." -- Romantic Times on A Christmas Waltz

Release date: May 26, 2011

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 385

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

When a Duke Says I Do

Jane Goodger

One of the more harrowing tasks of the servants of Mansfield Hall was searching for Miss Elsie, who had a tendency to fall asleep in the oddest places. They once found her balancing precariously on the edge of a fountain, one hand dangling in the water as carp nibbled curiously and painlessly upon her fingers. Though the servants always began their search in her rooms, it was almost inevitable that they would find her where she oughtn’t to be—and never in her bed.

“Don’t she look like an angel, though,” Missy Slater, Elsie’s personal maid, said, gazing down at her employer as she slept like the dead curled up in an oversized leather chair in her father’s library.

Mrs. Whitehouse, the housekeeper, was far less charitable, and scowled down at the sleeping girl. “As if I have time for this,” she grumbled, then cleared her throat loudly in an attempt to awaken her.

“You has to give ’er a good shake,” Missy said, doing just that. She was rewarded when Elsie’s moss-green eyes opened drowsily, and she smiled. She nearly always woke up smiling.

“What am I missing?” she asked, as she always did. She was feeling a bit groggy, for she must have been sleeping for at least an hour. The servants had been instructed to never awaken Elsie unless something of importance had happened.

“That Frenchie painter is here,” Missy said. “I know you wanted to be in the ballroom when your father met with him.”

“Monsieur Laurent Desmarais, Miss Elizabeth. He arrived not ten minutes ago,” Mrs. Whitehouse said, glaring at Missy for her familiarity. Missy made a face behind the housekeeper’s back and Elsie found herself trying not to smile at her maid. Just because she knew she should, she gave Missy a halfhearted stern look, which only caused the little maid to shrug innocently.

“Thank you, ladies,” she said, bouncing up, as if she hadn’t just been sound asleep. She patted her golden-brown hair, which was none worse for having been slept upon, and headed off to the ballroom. Having the great Laurent Desmarais paint a mural on their ballroom wall was a great coup for the Stanhope family. Usually, the famous muralist painted for no one beneath the level of a viscount, but her father, Baron Huntington, had more pounds than the typical baron, and apparently that income was more than Monsieur Desmarais could resist.

The Stanhope estate was in close proximity to the Dukeries, an area of Nottinghamshire that had an excessive number of dukes, making it a rather fortunate place for any family with girls of marrying age. Elsie had the good fortune of having been engaged to a future duke from the time she was an infant. At least, her father insisted it was good fortune. Elsie thought the idea of having her future laid out before her rather uninspiring.

Which was why having Monsieur Desmarais agree to paint their ballroom was so very exciting. So little of anything nearing excitement happened at Mansfield Hall.

Elsie lifted her skirts and ran, her slippers tap-tapping on the marble floor, as she hurried to the ballroom, a fairly new addition to their sprawling old home. There she found her father in deep discussion with a rather rotund-looking man, whose mustache was so thin, it looked as if it had been painted upon his face. His hair had too much pomade and his clothing looked about to burst away from his porcine body.

“Ah, this must be the beautiful Mademoiselle Elizabeth,” he said in his delightful French accent, and instantly Elsie forgave him his rather dubious charms. She’d conjured up a far more romantic image of the famous painter and felt rather ridiculous about that now.

Elsie dipped a curtsy. “Monsieur Desmarais, un plaisir,” she said, in impeccable French. “Veuillez m’appeler, Mademoiselle Elsie.”

“Of course. Mademoiselle Elsie. Lord Huntington was telling me a bit of your wishes. You require a large mural, no?”

“Yes. I would like it to cover this entire wall,” she said, indicating a large barren wall that had been stripped of all decoration in preparation for the muralist. A man was there, his back to them, laying out a drop cloth to protect the ballroom’s marble floor.

“My assistant, Andre,” Monsieur Desmarais said, nodding toward the man, who froze momentarily at the muralist’s words before continuing his work. “He does not speak, but he hears perfectly fine, the poor soul. He’s been with me since he was a boy. His English name is Alexander, but I call him by his French name.”

“How very charitable of you,” Elsie said.

Monsieur Desmarais puffed up a bit, seeming pleased by Elsie’s comment. “Do you have anything particular in mind for the mural?” he asked. “I understand you admired Lady Browning’s mural last Season.”

“Indeed I did. But I was thinking of something else. I was thinking of perhaps a lake.” She gave him an impish smile, acknowledging her whimsy. “A magical lake.”

“Magical?” Monsieur asked, with obvious skepticism.

Elsie smiled, her eyes full of merriment. “A secret lake might be a better description. Or one long forgotten. With a gazebo, at the far end.” From the corner of her eye, she could sense the assistant turning his head a bit as if to hear better what she was planning. “It’s painted white, but with paint chipping and rotted wood, perhaps. But I want it to look enchanted, not neglected, if you know what I mean. And in the center of the small lake”—she closed her eyes—“a rock formation, jutting out.”

At that moment a loud clatter sounded and Elsie opened her eyes. The mute had apparently dropped a supply of brushes. In rapid French, Monsieur chastised the younger man. “He is not usually so clumsy,” he said apologetically. “Usually as silent as a little mouse, that one.”

“Do you think you could paint that? I remember such a lake from my girlhood. There were no swans, but you may add some for visual interest or whatever you like.”

“Just a lake?”

“A secret lake,” she said, teasing. “I wonder if it would be possible to paint it as if someone is seeing it through branches or trees?”

“This would be difficult,” he said slowly, staring at the wall, his eyes falling briefly on his assistant. “But I think it can be done.”

“Wonderful,” Elsie said, clapping her hands together. “And will it be done in time for my birthday ball? I’ll be twenty-two on September the fourteenth. Is that enough time?”

“I will endeavor to complete the mural for you in time, Mademoiselle Elsie.”

“It shall be the best of all balls,” Elsie said, grabbing her father’s arm and hugging it to her. “Thank you, Father.”

Lord Huntington gazed down affectionately at his daughter, and Elsie smiled, a bit guiltily, up at him. She knew she could ask her father for the moon and the man would try to give it to her. And since her mother died three years before, he’d been even more indulgent. Even though she was already engaged—and had been for seventeen years—her father had given her a Season in London to introduce her to the society she would soon be an integral part of. Since her fiancé seemed to be in no hurry to marry, Elsie wanted to experience as much fun as she could before the daunting duties of being a duchess claimed her.

“It shall be a lovely mural,” Elsie said, watching as Monsieur Desmarais donned his smock. With a fine charcoal pencil, he began the barest outline of what Elsie knew would be a work of art. She knew, because Lady Browning’s rose garden mural was quite the most beautiful thing she’d seen. She’d half expected the air in the lady’s ballroom to smell of roses, so real and life-like was that fanciful garden. Lady Browning’s only complaint was that Desmarais had included a few fading blooms, which the countess claimed her gardener would never allow.

When Elsie saw that painting, the exquisite detail, the realness that made her feel as if she could walk right into that garden and touch a pointed thorn, she knew she had to have a mural of her own. She knew, without even thinking, what she wanted the subject matter to be. It had to be of that secret lake at Warbeck Abbey, where she and her sister had played, making believe they had discovered something truly magical. They’d never told a soul about the lake, about how they’d dangled bare toes into the cool water while sitting on a dock that was beginning to sag rather dangerously. Elsie and Christine had always dreaded their visits to Warbeck Abbey, for it was such a dour, strict place where the laughter of children seemed out of place. But after they’d discovered the lake, their visits had become far more tolerable.

The mural would be a happy reminder of her sister, who she still so desperately missed. They’d been twins, identical in nearly every way and inseparable, and her death twelve years earlier had affected Elsie profoundly.

“Let’s leave them to their work,” Elsie said, leading her father out of the ballroom. “I have about a dozen letters to write before meeting with the chef. Are you planning any dinner parties in the next few weeks, Father?”

“No, dear. Nothing special.”

Elsie frowned, and started to say something but stopped herself. Her birthday ball would be the first large social gathering they’d had at Mansfield Hall since her mother’s death. While many a man would have remarried already, Michael Stanhope missed his wife desperately and only recently had begun accepting invitations. If not for her aunt Diane, Elsie was quite certain she wouldn’t have had a Season at all. Her father simply had no interests other than wandering the countryside and collecting unusual lichens. They were quite beautiful, but his preoccupation with them was at times a bit worrying. He carried a magnifying glass and sketchbook with him and would disappear for hours at a time. He seemed content enough, but Elsie did worry about him.

Perhaps as much as her father worried about her. What a pair they were—a father who wandered the forest and a daughter who was afraid to fall asleep.

Like a dutiful girl, Elsie went to her room just after ten o’clock and donned her nightclothes as if she had every intention of going to bed. And like most nights, after Missy had said good night, she stared at her bed, that most hated of all places, and sat in a chair by the fire with a book, feeling her eyes burn from weariness.

Christine had died in her bed. Not the one that sat in Elsie’s room now; her mother and father had removed it long ago thinking that would help their remaining daughter rest. They’d even allowed her to change her room, but Elsie could not bring herself to do it, to lie in a bed without thinking about Christine, her sister and her heart, smiling over at her.

They were ten years old, and that night they had whispered to each other in the dark about how they would go into the forest and search for the haunted cottage one of the village children had told them about. Even though it sounded suspiciously like the German fairy tale, Hansel and Gretel, they convinced themselves that the cottage did, indeed exist. Hadn’t they found a secret lake by themselves? Certainly they could find a haunted cottage.

They fell asleep just as the moonlight was beginning to edge up her bed, but only Elsie woke up the next morning. She tried not to think about that moment, the awful realization, the instinctive, stomach-dropping knowledge, that her sister was gone. Christine had been cold and lifeless and even though Elsie had screamed for help, and screamed and screamed, she’d known her sister was dead. The loss was fathomless, and even now, years and years later, Elsie would sometimes miss her sister so much it was a physical ache.

So, no, Elsie did not go to bed that night. She hadn’t slept in a bed in twelve years. Christine was her twin, her second half, and when Elsie was still a child she’d decided that if she fell asleep in her bed, she would die, too. Someone would come into her room in the morning and find her cold, lifeless body, just as she had found Christine. Elsie knew she was being silly, but the fear was so ingrained, so much a part of her now, she simply could not do it. She’d tried, only to break into a cold sweat, then break down and cry. Over the years, her father had given up and let her wander the house at night, knowing it was the only thing that gave her comfort. When she was still a child, the servants would find her curled up in the library, fast asleep. She would awaken, frightened, confused until she realized where she was and that she was still breathing. And that Christine was still gone.

“You can be sure if I had a bed as comfortable as yours, I’d be sleepin’ in it,” Missy had told her once after spending a good deal of time looking for her.

“Don’t scold,” Elsie had said. “Perhaps I will tonight.” But she never did.

Elsie stared at her bed and told herself as she had every day since Christine’s death that nothing would happen to her if she just lay down, pulled the covers up to her chin and closed her eyes. But whenever she did that, she began to be aware of her breathing—in, out, in, out—so aware that it was difficult to breathe at all. With a little sigh of frustration, Elsie grabbed her wrap and pulled it on, then tip-toed to the door separating her room from the small one where Missy slept each night. Pressing her ear to the door, she could hear her maid’s soft snores, and smiled. A cannon could go off in her room and Missy would not hear it. Still, she opened her door quietly and stepped into the hall, lit only by a half-moon.

No one could navigate the house in the dark as well as Elsie. It wasn’t much of a talent, but she was rather proud of this ability anyway. She moved down the hall to the main staircase, walking quickly and quietly down the grand curving stairs on tip-toe.

Then stopped cold.

A light shone from the ballroom. A light never shone anywhere in this house at night. Ever. Elsie stared at that slice of light for a moment before deciding that perhaps Monsieur Desmarais must have left a lamp lit. She would have to talk to him about that, as a lit lamp could easily lead to a fire, especially in a home with a cat. Even though Sir Galahad was put out most nights, sometimes the servants could not find him and he remained indoors.

A noise from the room made her heart skitter. Certainly Monsieur Desmarais could not be working at this time of night. It was well after midnight. The ballroom could only be accessed from a set of double doors and several French doors that led to the outside terrace but which were always kept locked. Elsie considered sneaking outside and seeing who was in the room, but she’d not donned her slippers and the grass outside was sure to be cold and wet from dew. Holding her breath, she moved to the door, her hand on the latch, listening intently. Yes, there was someone—or something—in that room scratching about and it sounded much too large to be Sir Galahad. She pulled on the door latch, squeezing her eyes shut, and gave silent thanks to their well-trained staff who regularly oiled the doors to eliminate squeaks. A small slice of light lit her hand, hit her face, and she peeked inside. At the far end of the ballroom was a man, tall and powerful, making sweeping gestures along the wall. It took her a moment before she realized it must be Monsieur Desmarais’s assistant.

How curious. She watched as he drew on the wall, fine lines, outlining what would eventually be the mural. For long minutes she watched, fascinated with the sure way he worked, almost as if in a frenzy, slashing, moving about with controlled grace, hardly paying attention to what he was doing. Monsieur Desmarais was nowhere in sight. The room held only the couch and table she’d had placed there so she might read in the sunlight on cold days, for the ballroom was the sunniest, warmest place in the house in winter. In fact, the book she’d been reading still lay upon the table where she’d sat just that afternoon after the artist and his assistant had stopped for the day. Why was this man here now? And why was he doing what Monsieur Desmarais should be? For long minutes she watched him, and saw a vision slowly appearing before her—the lake, the rocks, the gazebo, and around it all the twining branches and vines. It was only the outline and already it was magnificent. And it had not been there this afternoon when she’d picked up her book. At that time, the wall had only a very few lines upon it, a grid of sorts and nothing more.

Elsie thought of the beautiful mural in Lady Browning’s home, and wondered if this man were the artist, not the famous muralist and knew, instinctively, that she was right.

She stepped into the room, not bothering to hide her entrance. “Good evening,” she said, and he froze, one hand poised to draw. He stood that way for several seconds before he slowly lowered his hand to his side. He was completely still, unnaturally so, as if he didn’t even dare take a breath. His loose white shirt was untucked, his sleeves rolled up revealing a strong, sinuous upper arm.

“Please don’t stop your work. I’m just fetching my book.” He continued to stare at the wall in front of him unmoving and she wondered if his face were disfigured in some way. “I won’t tell. I promise.”

Then he turned to her, as if curiosity overcame him, and stared in such an oddly intense way, Elsie felt uncomfortable. He was rather amazingly, disturbingly handsome. His hair was a deep chocolate brown, thick and unruly and far too long for convention. His eyes were some light color; she couldn’t quite tell in the lamplight. And his mouth was . . . Elsie had to look away. She shouldn’t be thinking about his mouth or the color of his eyes or anything else about him. As Monsieur Desmarais’s assistant, he was little more than a servant.

“I don’t care who paints the mural just as long as it gets done,” she said with measured casualness. “Did you do Lady Browning’s rose garden?”

He nodded slowly.

Elsie grinned, proud of her perception. “Oh, marvelous,” she said, clapping her hands together. “Please do continue to work. Don’t mind me and I won’t mind you. I’m afraid I find it difficult to sleep and often end up here. Quite improper, I know.” She grinned again and he simply stared at her. He couldn’t be daft. Certainly a man with such artistic talent had to be highly intelligent. Finally, he turned back to the wall, gripping the charcoal so tightly, she could see the tendons in his arms.

Alexander could not believe his misfortune. No one, in all these years, had ever discovered Monsieur Desmarais’s secret. Once, Monsieur had been the finest muralist in all of Britain, but rheumatism had made holding a pencil or paintbrush for more than a few minutes excruciatingly painful. It had been an insidious thing, taking away his ability a little at a time. By the time Monsieur could no longer do anything but supervise, Alexander had discovered his own talent, which was easily perfected with such a wonderful mentor.

Alex loved Monsieur Desmarais like a father and would die before the older man was shamed. He didn’t know if he could trust this girl, but it looked as if he was being forced to. If only she would go away. If only she would stop that incessant chatter.

“I think it should be rather nice to have company,” she said, sounding rather wistful.

He would not be good company for anyone, particularly not a girl who was apparently lonely and given to wandering about her house at night.

“I don’t sleep,” she said. He tensed again, as he always did when a stranger spoke to him. But he found himself relaxing a bit when he realized she did not expect him to respond and didn’t seem to care one bit whether he did or not. “Well, I do sleep, just not at night. And not in my b... my room,” she said, as if simply saying the word “bed” were naughty. Which it was, and he almost smiled.

Alexander had discovered there were two kinds of women: those who thought him a eunuch simply because he didn’t speak, and those who thought him good sport. When he was younger, he rather liked the latter. But this one was perhaps simply young and naïve. No good girl would spend time alone with a strange man in the middle of the night unless she was looking for a bit of naughtiness or was so innocent those naughty thoughts hadn’t entered her head.

He began working as she prattled on about her sleeping habits. He stared at the wall and frowned. Most of the detail would come later when he was painting, but now he was creating the scene, the perspective. He was used to doing pretty landscapes, fanciful castles in clouds, or mountain scenes. This mural, however, was different, and far more personal. No one could know, of course, what painting this lake was doing to him. It was like a knife to his soul, every slash of his charcoal tearing further into his damaged heart.

It was perhaps not entirely shocking that this girl would have seen the lake, that place he remembered with an odd mix of happiness and horror. Mansfield Hall was not far from where he’d grown up near a lake very much like the one the girl described. Enough time had passed that he very much doubted anyone would recognize him. He’d rarely been brought out into society even as a child, for fear he would humiliate himself. And, of course, his father. While his brother would bow and say all the proper things a boy should say to adults, Alexander never could. He would stand there, his eyes wide open, frozen as if a lump of ice around his throat prevented him from speaking. Such a scene had played out more than once, followed by a thrashing, before his father had given up on him entirely. The last time, the worst by far, didn’t bear thinking about at all.

His father had been deeply ashamed of his second son, but Alexander had still been surprised when his father had committed him to an asylum for the mentally deficient one month after his brother’s death. And there, he’d been forgotten. They probably still thought him there, that sad place where the aristocracy placed their unwanted offspring, the deficient ones that were an embarrassment.

He’d been so lost in thought, he hadn’t heard the girl come up next to him. She traced a line he’d drawn with one finger. “The rock,” she said, a smile on her lips. She oughtn’t to be so close to him. She smelled sweet and looked sweeter. Her wavy red-gold-brown hair falling down her back, her green eyes sweeping along the line he’d drawn. He hadn’t seen what she looked like that afternoon, and she’d been in the shadows this evening. Now that she stood bathed in the soft light of his lamp, he realized she was beyond exquisite. “It looks exactly as I pictured it.” She gave him a curious look, a small tilt of her head before returning to the couch and her book.

“It’s special to me, that lake,” she said, her voice echoing in the emptiness of the vast room.

He wished he could tell her to stop talking, to leave him alone. But he knew from painful experience that once someone who thought him mute discovered he could talk, their reaction was humiliatingly jubilant, as if they had somehow “cured” him. Other times people felt angry and betrayed, and he supposed that was how his father had felt. For he could easily talk to his mother, even to his tutor, but in front of his father, he froze. He never spoke to someone who knew he could not speak, and he rarely got a chance to speak to anyone else. He liked his silent world of paint and charcoal and beauty—a world this girl was disrupting.

“My sister and I discovered the lake,” she said. “It’s surrounded by a huge hedge and shrouded with mystery. We found it at Warbeck Abbey. Have you ever been?”

Alexander ignored her, ignored the fear that sliced through him at the mention of that terrible place.

“No one ever speaks of the lake and why there’s a large hedge surrounding it.” He willed himself to keep working, even as nightmarish images filled his head. “Of course, we were children and told in no uncertain terms that we should stay away from the hedge, that there were monsters on the other side. We couldn’t resist,” she said, laughing. “We walked around it until we discovered the smallest hole in the hedge. How brave we were, for we actually thought there might be a monster. Christine went first. She was my twin, but she was always far braver than I. We were exactly alike in every other way.” She paused and Alexander thought she was finished.

“On the other side of that huge hedg. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...