- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

An unlucky-at-love veteran gets more than he bargained for from his matchmaker in this Victorian romance by the author of When a Lord Needs a Lady.

Mr. Charles Norris needs help finding a wife . . .

For he has the unfortunate habit of falling for each Season’s loveliest debutante, only to have his heart broken when she weds another. Surely Lady Marjorie Penwhistle can help him. She’s sensible, clever, knows the ton, and must marry a peer, which he is not. Since she’s decidedly out of his reach, Charles is free to enjoy her refreshing honesty—and her unexpectedly enticing kisses . . .

Lady Marjorie Penwhistle doesn’t want a husband . . .

At least not the titled-but-unbearable suitors her mother is determined she wed. She’d rather stay unmarried and look after her eccentric brother. Still, advising Mr. Norris is a most exciting secret diversion. After all, how hard will it be to match-make someone so forthright, honorable, and downright handsome? It's not as if she’s in danger of finding Charles all-too-irresistible herself . . .

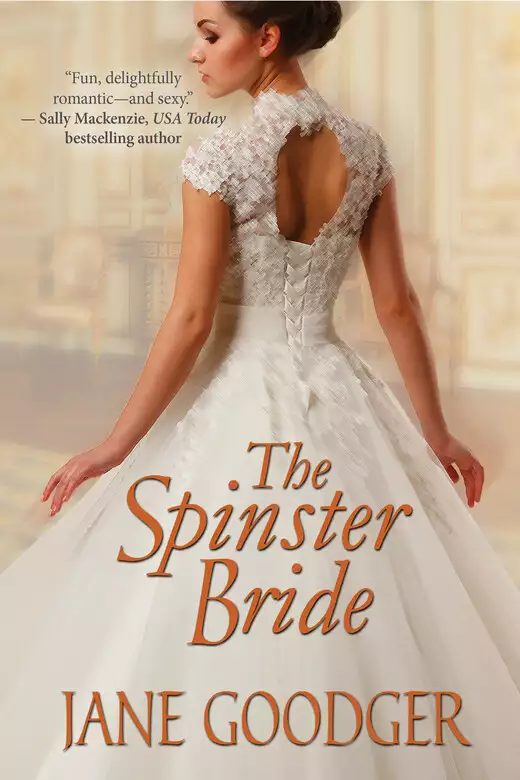

Praise for The Spinster Bride

“Alternates between being funny thanks to spot on humorous dialog and heart wrenchingly realistic due to Jane Goodger's attention to detail and accuracy.” —Fresh FictionRelease date: February 3, 2015

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Spinster Bride

Jane Goodger

She had been overlooked.

As she stood in the ballroom next to her mother, she noticed an odd phenomenon. All the young swains who used to hover around her were now hovering around Miss Lavinia Crawford. Marjorie was, by London society standards, quite old to not be married. At twenty-three (and very nearly twenty-four), she was, of course, still lovely, but there were lovelier—and younger—women, fresh to the marriage market, full of laughter and life while Marjorie had to admit she was a bit . . . jaded.

“Miss Crawford seems to be drawing quite a crowd,” she said to her mother. One look told Marjorie that her mother had noted the same thing.

With eyes narrowed, Dorothea Penwhistle, Lady Summerfield, said, “They’ll stop flocking around her once she opens her mouth to speak. I have never heard such a high-pitched screeching sound come out of a young lady’s mouth.”

Marjorie chuckled and her mother looked pleased by her reaction. Miss Crawford did, indeed, have a voice normally found in a ten-year-old child, but, despite her mother’s comment, the young men by her side didn’t seem at all bothered by it. Marjorie pressed her lips together, earning a sharp look from her mother. She forcibly relaxed her mouth, turning it up into a pleasant smile meant to convey both confidence and feminine charm. It was a smile she’d practiced in front of the mirror any number of times, with her mother by her side offering suggestions.

Marjorie had been the rather miraculous product of two exceedingly homely people. Her long-dead father (some said her mother had killed the man with one of her lethal looks) had been short, fat, and balding, with a bulbous, cratered nose and plump lips. His one pleasant feature, deep gray eyes rimmed with blue, Marjorie had inherited. Dorothea had been his perfect match—a sturdy, square-jawed woman with iron gray hair (even in her late twenties), and small brown eyes dominated by strong, thick eyebrows that needed trimming once a week.

Marjorie was slightly taller than her father and her mother, and had been blessed with a lovely face, thick dark curls, and a trim, feminine figure that, until this season, had attracted a large bevy of suitors. She knew her lack of beaus perhaps had as much to do with her age as the fact she’d rejected nearly everyone who had approached her. The pool of suitable men was rapidly dwindling, thanks not only to her pickiness, but also to her mother’s insistence that she marry only a title. It was quite known among the ton that unless one had a lofty title (a mere baron would never do—at least not until this point) one did not approach Lady Marjorie Penwhistle and ask for even as much as a dance. If Marjorie were honest, she’d enjoyed her discerning reputation the first two years after coming out, but was weary of it now. She wondered if her mother were even aware that Marjorie was no longer the belle of the season.

“She’s rather like a delicate canary surrounded by hungry cats,” Marjorie said of Lavinia in her mother’s ear, gaining her a grin.

It was easy to please her mother. Marjorie need only breathe to make her mother happy. She knew her mother believed Marjorie was the product of her own hard work, a piece of art to proudly be put on display. Marjorie loved her mother dearly, but often found herself disliking her. The burden of always being the good child, the beautiful one, the charming and special one, grew tiresome. If she were the golden child, her poor brother George was the pariah. George, with all his wonderful imperfections, bitterly embarrassed their mother. Sweet George, who didn’t have a mean bone in his lanky body, was the object of Lady Summerfield’s scorn. And so, as much as Marjorie loved her mother, she disliked her, too. Disliked the way she treated her beloved brother, the way her eyes turned cold when he walked into a room.

Something was off about the young man sitting across the card table, but Charles couldn’t quite put his finger on it. It was more than his unruly and rather horrifyingly red hair or the strangely intense way he was looking at his cards. The young man, who could be no more than twenty years of age, kept losing—mostly to him. And yet, his expression never altered, even when his older friend lost. He didn’t sweat or swear. He didn’t engage in any of the banter the others exchanged after a disastrous hand, the kind of verbal volley that was meant to announce to the others that losing five hundred pounds in a single hand was merely a drop in the bucket. It looked as if he didn’t truly care whether he won or not.

And Charles had yet to meet a man who truly didn’t care.

Hand after hand, the young man stared at the table or at his cards as they were dealt to him. He played poorly, mostly because he never looked around him, didn’t bother trying to see if his mates were telegraphing the kinds of cards they held. Sir Robert, for example, would pull at his untamed eyebrows when he had a particularly poor hand, and sit stock-still when he had a very good one. Lord Hefford would clear his throat when he was a bit excited about his hand; Lord Pendergast would slouch. And the young man’s friend (he couldn’t recall his name even though they’d been introduced) tugged on his collar when his hand was particularly bad. Their tells were easy to pick up if one were actually looking.

But the young man had no tells, for his expression never varied. Charles knew this because he stared at the young man hand after hand, watched his eyes darting over his cards. He knew how to play, that was certain. He bid well when he had a bidding hand. But because he didn’t look around, he had no idea what the other men held. And that’s how Charles won hand after hand, until the young man realized, much to his surprise apparently, that he’d accrued a debt of nearly twenty-five thousand pounds. It was an enormous sum. A devastating one. And yet . . . surprise was as far as it went when the men were finished and the damage totaled, as if the young man had taken a bite of something that looked sweet and found that instead it tasted sour. Such a curious reaction.

Charles knew very few men—particularly young ones—who would not have vomited after losing such a stunning amount of money. Or started to weep. Instead, the young man said with resignation, “Oh, dear. Mother will be very angry.”

The game broke up and Charles eyed the young man carefully. He’d heard of men taking drastic measures after losing such a sum, and he hardly wanted to feel guilty after the fellow committed suicide. Charles pulled him aside so as not to humiliate the fellow.

“Sir, do you need time to settle your debt?” he asked the younger man. Charles studied his face for any signs of distress. There were none.

“I lost a total of twenty-four thousand, five hundred and seventy-five pounds,” the young man said, bobbing his head slightly in cadence to his words. “I owe you twenty-four thousand, five hundred and thirty-two pounds. I have thirteen thousand, two hundred and twenty-two pounds in my account at Baring’s.”

Charles grimaced. “So, you do need time.”

“I need eleven thousand three hundred and ten pounds in order to make good on my debt to you.”

“Of course.” Charles furrowed his brow. Something wasn’t quite right. The man obviously was intelligent enough to do high figures in his head, but it was the manner in which he was speaking that told Charles that he was a bit of an odd duck. “And do you have that amount?”

“No.” That word was said with the same inflection one might use to refuse a drink of water.

“Allow me to introduce myself. I am Mr. Charles Norris.” The man continued to stare just off to Charles’s right side, not meeting his eyes, though he did dart him a look or two. The young man held out his hand and the two shook.

“I am George Penwhistle, Earl of Summerfield.”

Charles’s brows shot up and he took a moment to consider. “Your sister is Lady Marjorie?” He remembered meeting Lady Marjorie and her bulldog of a mother at a house party last fall. Lady Marjorie’s name, which had appeared on his list of potential brides, had a large and definitive “X” by it. Her mother not only frightened him, but she also insisted with a ferocity he’d never seen—and that was quite the statement—that her daughter only marry a titled man. Alas, Charles, a second son of a viscount with a brother who already had three strapping male children, was quite far down the list of heirs.

George smiled for the first time. “Marjorie is my older sister,” he said enthusiastically. “She is two years, nine months, and two days older than I.”

“I see.” Charles was beginning to see very clearly, indeed. Though the man demonstrated keen intelligence, something wasn’t quite right. Charles hadn’t been back in England long enough to be privy to all the gossip, but now that he thought about it, his fellow card players had seemed a bit reticent about welcoming Summerfield to their table. He could not take money from this man, for he obviously didn’t have all his wits about him.

“I’ll tell you what, Lord Summerfield. I’ll forgive your debt if you do me one favor. Wait here.”

Five minutes later, when Charles returned with a sealed envelope, Summerfield was standing precisely where he’d left him. He fleetingly wondered how long the young man would have stood there if he hadn’t returned. “Give this to your sister, will you? It is a matter of vital importance.”

Marjorie wished her brother were here. Instead, he was out with their cousin, Jeffrey, a nice enough chap if you liked sullen men who constantly complained of their lack of funds. Ironically, the two were playing cards at their club. Marjorie gazed around the room, then halted when she saw the familiar shock of her brother’s bright red hair. Next to her, her mother stiffened, and Marjorie’s stomach twisted, to see the object of her thoughts walking toward them.

“Good God, he’s not even dressed,” Dorothea said with horror.

“He’s dressed, dear Mother, just not properly.” Marjorie gave George an affectionate smile. He was wearing an informal suit with a bright green vest and mustard-yellow cravat. His hair, never truly tamed, was particularly messy, as if he’d been out in a windstorm.

Marjorie left her mother’s side to intercept him and lead him away from their parent. “I wasn’t expecting you this evening, George,” she said, looping her arm affectionately around one of his. “And from your dress, I don’t believe you were, either.”

“Mother is going to be so angry, Marjorie,” George said, swallowing thickly. He sounded frightened to death.

Marjorie felt the blood drain from her head, and she pulled him into a hall for even more privacy and to get away from her mother’s prying eyes. “What’s happened, George?”

“I like playing cards at school. I’m good at it, too. I almost always win because I know what cards there are. I keep track of what’s left, you see.”

“You gamble, George?” Marjorie asked, dreading what was to come.

“Only for a few pence at school. But I went to the club—it’s Wednesday, you know.”

Yes, Marjorie knew what day it was and also knew that on every Wednesday George went to his club without fail. However, she’d never known him to join a card game.

“I saw Lord Hefford and Lord Pendergast and asked if I could join their game. A Mr. Norris was there, too.”

“Charles Norris?” Marjorie asked, with the feeling of dread growing. She’d met Charles Norris during a house party. The boisterous Mr. Norris had briefly pursued her dear friend Katherine Wright, now the Countess of Avonleigh.

“Yes. Charles Norris. He won a lot of money from me.”

Marjorie could feel sweat forming along her hairline as her trepidation grew. Surely Mr. Norris would not take money from George. Then again, perhaps he hadn’t noticed that her brother was slightly . . . off. Oh, she adored George, but she worried about him in social situations. He was brilliant researching law, which was why he was a solicitor, but he’d never be an effective barrister. He was, to say the least, awkward. “How much money did he win, George?”

“Twenty-four thousand, five hundred and thirty-two pounds.”

What little blood was left in her head drained away and Marjorie actually swayed. “Oh, no, George.” She knew it wasn’t the loss of money that was the most important thing, it was that George had lost the money. If it had been Marjorie, her mother would have forgiven it, would have even laughed at her daughter’s silly folly. But this was George and he would never be forgiven. It was simply another flaw that would never be overlooked, another reason for her mother to claim he was not worthy of the title. How many times had her mother said aloud that she wished she could petition the House of Lords to remove his title? Even Lady Summerfield knew that was a nearly impossible task. But losing such a sum? It would simply add fodder to her claims of incompetence. Poor George would not fare well in any public hearing.

“It’s all right, Margie. He said he’d forgive the debt. He gave me this note to deliver to you.”

The relief she felt was nearly as strong as the fear she’d experienced just moments before. Perhaps Mr. Norris was a good, fair man who realized George likely didn’t understand the enormity of what he’d done.

Marjorie took the note, suspecting it was simply an explanation of the evening’s events.

The dread came back in force. Immediately? It was nearly one in the morning. She couldn’t possibly . . .

Oh, she would have to, drat it all. Marjorie looked up at George, angry with her brother for putting her in such a situation. And frustrated that he seemed so completely oblivious to this fact. “George, I am very, very angry with you.”

“You are?”

“Yes. You are never to gamble again, do you understand me, George? Never.”

George ducked his head, his pale, freckled cheeks turning scarlet. Marjorie instantly felt remorseful, for she couldn’t remember the last time she’d raised her voice to George. Using a softer tone, she said, “This was very bad of you, George. He has not forgiven the debt but has requested a meeting. Thank goodness he’s asked to see me and not Mother.”

George couldn’t know how very improper such a request was, and if she felt she had a choice, she would have refused. But how could she? If Mr. Norris did not forgive the debt, her mother would surely take steps to remove George from society. Why would any gentleman demand to see an unmarried woman in his townhouse at such a disreputable hour? For all his flaws—and Marjorie had noted quite a few in their brief acquaintance—she had thought him to be a gentleman.

She tried to remember what she did know of the man, but came up with a woefully small amount of information. If she remembered correctly, he was the second son of Viscount Hartley, and a diplomat of some sort who’d recently returned from somewhere.

She gave an inward shrug. She’d no doubt find out more about his motives in a few minutes, for his home on Bury Street wasn’t far from where she stood now. If it weren’t for the hour, they could have walked.

“You will accompany me to his townhouse, George, but wait in the carriage. If I do not return outside in twenty minutes, you are to knock loudly on the door and demand entrance.”

George, with his head still down, nodded.

“I’m not still angry with you, George. Well, perhaps a bit. But I will have that promise from you about gambling. Never again, George. It’s clear you have no talent for it.”

“I was a champion at school,” George said. “I won six pounds, seven pence.”

“But those were boys. You were playing against men tonight who have been gambling for years. No more, George. Promise.”

George looked up. “I promise, Margie.”

Marjorie smiled. “Good. Now let’s call your carriage. It’s likely not blocked in as you just arrived.”

Marjorie, with much protestation from her mother, finally was released from the ball after pleading a dreadful headache. She admonished her mother, who was having a grand time with her dear old friend, Lady Benningford, to stay and enjoy the evening.

“I’ll see you in the morning, Mother,” Marjorie said, kissing her mother on the cheek. “You have fun. When was the last time you had a good time just for you?”

Dorothea smiled at her fondly and let her go, noting aloud that Marjorie did look a bit peaked and perhaps that explained why so few young men had shown an interest in her that evening. Marjorie forced herself to agree with her mother, even though she resented her mother’s ability to bring every conversation back to their quest for a husband.

Once in the carriage, seated across from her brother, Marjorie tried to remain calm. Those words in the cryptic note nagged at her— “negotiate the terms.” What on earth could he mean by that? Her imagination suggested every scenario from her hand in marriage, to her virtue, or one of her family’s properties. But if he wanted a property, couldn’t he have negotiated that with George? Her brother was the head of the family and quite capable of such a negotiation.

Oh, God, would he want . . . favors? Her stomach twisted as she tried to recall anything she could about Charles Norris. He was a gentleman—at least he had been raised that way. His brother, heir to the viscountcy, was a highly respected man with an excellent reputation. She tried to recall Mr. Norris from when he’d pursued Katherine. Mr. Norris was large, boisterous and . . . handsome. He was appealing if one liked large, boisterous men. And, frustratingly, that was all she could recall of him. He’d gone to a cricket match with Lord Avonleigh and her friend Katherine. She remembered only because she’d been seated not far away and she’d found him rather overly enthusiastic about the game whilst trying to teach Katherine all about it.

“What was Mr. Norris like? What was his disposition?” she asked. “Was he nice?”

“Oh, yes. He smiled at me and that meant he liked me. Didn’t it?” George asked uncertainly.

“I’m sure he was quite happy after winning that sum of money,” Marjorie muttered.

“No. I don’t think so. That’s why he is giving the money back. He asked me if I had the money, and I told him that I only have thirteen thousand, two hundred and twenty-two pounds in my account at Baring’s. That means I need eleven thousand three hundred and ten pounds.”

“That’s still quite a sum,” Marjorie said. “What exactly did he say to you?”

“He said, ‘Sir, do you need time to settle your debt?’ and then he asked me to give you the note.”

Marjorie furrowed her brow in thought. She supposed the only way to find out Mr. Norris’s intentions was to meet with him. She just wished it wasn’t at this hour of the early morning.

In short order, the carriage pulled up in front of the townhouse on fashionable Bury Street, not far from St. James’s Square. The streets were deserted, but well lit by gas lamps hissing in the quiet of the night. With a deep sigh, Marjorie stepped down from the carriage, ignoring the concerned look of their footman, and walked up the steps to the front door. Twisting the bell, she stepped back, clutching her fists to her stomach in a desperate attempt to squelch the sick nervousness settling there. She barely had time to collect herself when the door opened to a tall Indian man wearing a traditional dhoti and white turban.

“Lady Marjorie, please come in. Mr. Norris is expecting you.”

“Lovely,” Marjorie said, stepping into the dimly lit entry hall.

“This way.” The servant walked down a long, dark hall, which only added to the trepidation in her heart. She thought she heard a strange grunting sound coming from the direction of their path, and she stopped dead.

The man turned toward her inquiringly.

“I . . . Are there no lights?”

“Ah, forgive my rudeness. I am used to walking these halls in the darkness and quite forgot you are not familiar with this house.” He pulled a match from his pocket and lit a wall sconce. “Better, no?”

Marjorie smiled. “Much better, thank you.”

“Now we can contin—” His sentence was interrupted by a very loud and very foul curse. “Nighttime can be difficult for Mr. Norris,” the Indian said cryptically, before continuing down the hall.

“Perhaps another time would be better?” Marjorie called after him.

He turned again, smiling pleasantly. “This way, my lady.”

With a sigh of resignation, Marjorie began walking toward the end of the hall, stopping when the man knocked softly at a door, which showed a dim light underneath. Here they would no doubt find the loud and foul-mouthed Mr. Norris.

“Goddamnit, Prajit, if she ain’t here yet, leave me the fuck alone!”

“Perhaps I should come back at a more respectable hour, sir?”

Charles spun around from his spot by the fire where he’d stood, hoping the warmth of the flames would soothe the agonizing pain shooting through his leg. He muttered yet another curse, clenched his jaw, and forced a smile, which even he knew probably made him look like a madman.

“Lady Marjorie, I apologize for the lateness of the hour, but I wanted this resolved as soon as possible.”

Through the haze of pain, he was aware the lady was dressed for a ball, and he had enough wits about him to realize she’d been pulled from said ball to attend him. “And I apologize again for taking you from what I imagine was a pleasant evening.”

“Perhaps more pleasant than this,” she said, raising one brow in her lovely face.

Now that she was in front of him, he realized he remembered her quite well. It was rather difficult to meet Lady Marjorie Penwhistle and not remember her. She was, in fact, every Englishman’s fantasy of what an English woman should look like—if one preferred dark-haired beauties as opposed to blondes. Her complexion was near perfection, creamy and smooth with the slightest blush along her delicate cheekbones. Her nose was small, her chin perhaps a bit strong (a gift, no doubt, from her mother), but she was in no way mannish. Her eyes were dark, and in this light, he couldn’t tell if they were dark blue or perhaps brown. Her entire countenance gave her an air of authority and intelligence—and coldness. No, he wasn’t the least bit attracted to her.

She would be perfect for him.

“Please sit down, Lady Marjorie.”

She hesitated, not wanting to be put at a disadvantage, but realized she was already so at a disadvantage she might as well do as he asked. Or rather demanded, even if politely. She sat and looked at him expectantly, fear trickling down her spine.

They were in a small room, crowded with furniture and books and things that had been collected, no doubt, from his travels. Foreign and frightening-looking things filled the room, things that would be fine for a museum but were a bit off-putting in a parlor. And at the center of this small room was a large man standing by the fire as if he were some sort of medieval king. His hair was an odd color—neither blond nor red nor brown, but somewhere in between and with shots of all of those colors streaking through it. At the moment, it was rather unkempt, tousled one might say. His eyes—a brooding dark brown—were staring at her. One hand was fisted tightly on the mantel, and when he saw her look curiously at that white-knuckled fist, he carefully loosened it and shoved it into one pocket.

“Your brother has told you what happened this evening?”

“Yes, he did. Though I’m not certain George fully understands the scope of his debt.”

“He knows how much he owes me.”

“Oh, yes, he does,” she said agreeably. “But he doesn’t fully understand the repercussions of accumulating such debt. My brother is frightfully smart about certain things. But he struggles with the intricacies of society.”

“He’s a pleasant young man, but a bit of an odd duck. I did notice that.”

Marjorie smiled. “Yes, that’s about right. Why have you asked me here, sir? Surely you don’t think I can come up with the amount he owes.”

Mr. Norris took a step away from the mantel and let out a low sound, his face contorting in pain. Marjorie stood and started moving forward, but he held out a hand, staying her. “Get out, Prajit. I am fine. For God’s sake.”

Marjorie turned to see his manservant standing at the doorway, his expression filled with concern. He backed out and silently closed the door, leaving them alone again.

“You are injured?”

“In Ghana. The Ashanti War.”

Marjorie nodded. Even though she knew very little about the war, she and everyone else in England had heard about General Garnet Wolseley and his efforts there. “Did you meet G. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...