- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

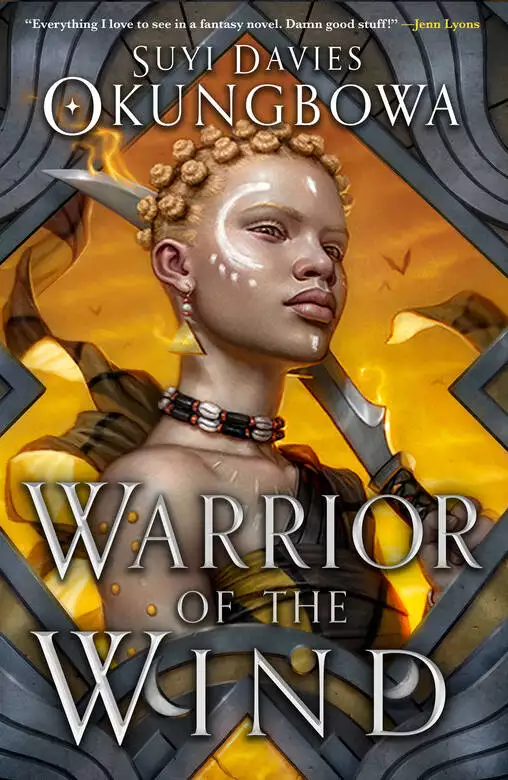

Synopsis

From city streets where secrets are bartered for gold to forests teeming with fabled beasts, Suyi Davies Okungbowa's sweeping epic of forgotten magic and violent conquests continues in this richly drawn fantasy inspired by the pre-colonial empires of West Africa.

There is no peace in the season of the Red Emperor.

Traumatized by their escape from Bassa, Lilong and Danso have found safety in a vagabond colony on the edge of the emperor’s control. But time is running out on their refuge. A new bounty makes every person a threat, and whispers of magic have roused those eager for their own power.

Lilong is determined to return the Diwi—the ibor heirloom—to her people. It’s the only way to keep it safe from Esheme’s insatiable desire. The journey home will be long, filled with twists and treachery, unexpected allies and fabled enemies.

But surviving the journey is the least of their problems.

Something ancient and uncontrollable awakens. Trouble heads for Bassa, and the continent of Oon will need more than ibor to fix what's coming.

Praise for The Nameless Republic:

"A thrilling, fantastical adventure that introduces a beguiling new world . . . and then rips apart everything you think you know."—S. A. Chakraborty

"An original and fascinating epic fantasy full of bold characters, bloody action, and brutal politics.”―James Islington

The Nameless Republic

Son of the Storm

Warrior of the Wind

Release date: November 21, 2023

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warrior of the Wind

Suyi Davies Okungbowa

Fifth Mooncycle, 19–21

CHABO WAS A COLONY of vagabonds.

Every soul in Chabo was running from something. People of disrepute who, if their feet were to touch the dust of any city or settlement in the Savanna Belt, would be pounced upon and sent into a forever darkness. Those who lacked ambition, aspiration, or resourcefulness, making Chabo the only place on the continent that would not eat them alive for it. Those who moved between worlds, who needed a place of dishonour that operated by its own rules to pause and rethink their strategies.

Chabo asked nothing of those who came. There were no councils, no civic guards, no warrant chiefs, no vigilantes, no peace officers. Nothing but a haphazard collection of rogue communes in the western armpit of the Savanna Belt. It was generally agreed that any soul without a wish to be absorbed into this colony was to remain on the northward trade routes that sprouted from Chugoko, a real city. It was advised not to turn even one’s neck westward, let alone one’s kwaga.

Except, of course, if one wanted to turn their sights on Chabo in search of something that did not wish to be found.

Five mooncycles into the second season of the Red Emperor, a wagon carrying five men turned westward like so, sidling the Soke mountains and border moats, and set themselves upon the Lonely Roads West to Chabo. Each man was dressed in armoured hunthand garb—skirts, chest plates, iron headwear—and bore a short spear and long blade. Faces half shielded by veils, eyes alone betraying grim temperament. In their wagon: shackles, blindfolds, an iron crossbolt.

They rode in the open wagon and spat in the browning grass by the wayside, not an eye taken off the roads, minds focused on the colony ahead of them. They camped without event on the first day. By the next day, they came upon the first person they had seen in a long time: a wrinkled old desertlander who sat in the dust and batted flies from his lips.

They kicked aside his alms bowl and shoved a worn leaflet into his nose.

“In the name of the Red Emperor, tell us what you know of this,” the leader of the hunthands—a dark man with tribal marks etched into his cheeks, remnants of his hinterland origins—said in halting Savanna Common.

The almsman cocked his head and licked his dry, cracked lips. He squinted at the sheet of paper, struggling to make out the faint markings in the glare of the sun. It was unclear what language the words were written in. Besides, the man couldn’t read. He shrugged after trying, pointed at his ear, then at his head, to say he understood neither their words nor the markings.

“We seek the jali who made this,” said the leader, switching to a smoother border pidgin, more easily understood. “We are led to believe it came from Chabo.”

The almsman shrugged again. The leader smacked him on the cheek.

“Listen, you millipede,” he said. “This jali and his accomplices are fugitives of the Red Emperor. If you have seen a Shashi in Chabo, you better tell us now.” When the almsman struggled to process the word Shashi, the leader added: “He rides a dead bat that is not dead, and can call on lightning. He may be travelling with a yellowskin.”

The almsman blinked at that, then stifled a chuckle, and that was all it took.

One of the men punched him in the face and broke his nose. They left him bleeding into the dry grass, red reflecting in the hard heat of noon.

Next, they came upon a nomadic group of cattle and goat rearers. They stopped and asked the same questions. The rearers, a ragtag group of poorly armed men, said they sounded ridiculous. A bat-riding Shashi and a yellowskin? They had walked the length and breadth of this Savanna Belt and had never seen such things. They waved the hunthands aside and asked to be left alone.

One of the hunthands took off his veil to reveal his mouth: lips sewn shut, copper wires criss-crossing top to bottom, leaving dark, reddish patterns where they pierced.

Immediately the nomads saw this, they fell to their knees, heads bowed in the sand. “We did not know you were the Red Emperor’s peace officers,” they pleaded. “We thought you were bandits or swindlers trying to take our goats.”

The lead hunthand, in response, mounted the crossbolt and shot it between three goats. The rearers swallowed their hurt and rage and sorrow as the hunthands made them chop up the meat, dry it over a fire, and salt it for the rest of their trip.

On the third day, a few hours outside of Chabo, the hunthands met another vagabond.

This man happened to be headed away from Chabo, toward Chugoko, and luckily for them, knew about the tract. He had seen others like it being read back in Chabo, passed from hand to hand. All nonsense stories, he said, lies about the Red Emperor and Bassa. But it was popular in the colony, often read around night-fires among the companies that plied their trade there.

They thanked him, but for good measure, stripped him of his belongings.

They had barely gone another hour when they met another vagabond, this one cloaked in every sense of the word. Their wrappers went up to their wrists and ankles, and a veil shielded their face, leaving only their eyes visible. Even their hands and feet were wrapped in strips of cloth, as if they’d once been buried beneath the sand.

Upon sighting the hunthands from afar, the vagabond stopped in the middle of the road.

The men, unsure of what they were dealing with, disembarked from their wagon. The leader shouted his questions—in Savanna Common, in Mainland Common, in two border pidgins. None evoked any response. Then the man with the sewn lips revealed his face, and the vagabond snickered.

“If you were truly peace officers,” the vagabond said in High Bassai, “I would already be dead.”

The leader’s eyes narrowed. The man with the sewn lips removed the false wiring, tossed it in the sand, and wiped the fake blood from his lips.

“Who are you?” asked the leader.

“Come and find out,” said the vagabond, then ducked into the bush.

The men moved before they thought, drawing, unsheathing, a synergy born of seasons of hunts together. They piled into the bush, but one ran to the wagon, mounted the crossbolt, aimed it in the general vicinity of the vagabond, and fired. The iron bolt whizzed through tall grass, parting vegetation, headed for the retreating figure’s spine.

Out of nowhere, a flash of colour, as a gem-hilted blade appeared and struck the crossbolt clean in the head, altering its trajectory. The bolt missed the vagabond narrowly, tearing through their wrappers, splintering one tree, embedding itself into another.

“Ambush!” cried the leader, but it was too late. The vagabond had stopped running and had now turned to face them.

A second figure materialized in the grass: a man in a boubou kaftan, head in a turban, the curved sword in his hand pointed at the hunthand leader. Various people dressed and armed in a similar manner began to appear, their curved swords pointed likewise. In a moment, the hunthands were outnumbered, outarmed, outfoxed.

“If you know what is good for you,” the man in the boubou said, “drop your weapons.”

The lead hunthand, though not fully understanding the Savanna Common spoken, recognised the language of a well-executed trap. Especially once he spotted the vagabond from much earlier—the one who’d told them about the tract—among the group.

He surrendered his weapons and signaled for his men to do the same.

The cloaked vagabond stepped forward. Up close, he could see it was a woman: young, low-brown, desertlander. Raised scars peeked out near her collarbone, stretched and leathery, as if belonging to some other skin.

“You will be returning those,” she said, of the belongings they stole.

The lead hunthand nodded solemnly, then asked again, softer this time: “Who are you?”

“We,” she said, “are the Gaddo Company.”

Chabo

Fifth Mooncycle, 21, same day

LILONG RODE BACK TO the colony beside Kubra, in the lead and on the kwaga gifted to her by the company. This was how crucial she had become to company affairs over the few mooncycles since her arrival. So integrated, in fact, that she barely spared a thought for their targets anymore, especially when they deserved it like the hunthands they had just stripped of everything and abandoned in the savanna.

It’d started with Kubra asking her to join their raids. Not a request per se: It was customary for Bassa escapees to work off the cost of their escape. Between the four in her group, Lilong was the best choice, being the most skilled, most easily adaptable, and least recognised.

Initially, she’d accompanied them only on food raids, robbing Bassai merchant caravans along the trade routes. But the caravans soon became harder to defeat as the routes saw increased patrols by the Red Emperor’s bounty force of peace officers. So Lilong opted instead to provide first points of attack closer to home, fitting so seamlessly into the role that, within the season, she had become Kubra’s second-in-command.

They rode into the colony through the widest of the four mainways, that which contained both the depository and the public house. At this time of day—early evening—a motley selection of people milled about at the height of their business. There were no stables, so most tended to their mounts—camels and kwagas both—in back corridors. Most also trained their wild beasts in the street, like the feral camel that spat in Lilong’s direction as they went by, the owner trying to rein it in.

Chabo welcomed them as it often did: by paying no attention at all. The colony had a character of its own, a spirit of organised chaos that possessed all who arrived here. It had to be a possession, Lilong surmised, since no matter how deadly a vagrant one was before joining the colony, it was only a matter of time before they turned out differently (though worse in other ways, she thought with an eye on their tattered clothing, rotten teeth, and general lack of hygiene).

There was an odd sense of belonging one developed to the place, something Lilong had sorely missed in all her time traipsing the mainland. The full-bellied laughter of colourful strangers who did not wish her death, and whom she did not want to strangle in turn. Singing by the night-fire. Combat training with fighters she barely knew yet shared a common goal with.

But that feeling, she reminded herself often, was dangerous. No one here had anything in common with her. No one here had to return home—a home that awaited with jaws open—to reclaim their family’s honour. No one here held the future of the continent in their hands.

“It’s time,” said Kubra, pulling Lilong out of her thoughts.

She blinked. “For what?”

“The meeting. The audience with Gaddo you asked for?”

Lilong’s eyes narrowed. “You said after fifty successful raids. I have not done fifty.”

“And yet they would like to see you anyway,” said Kubra. “Something urgent. Come by our quarters tonight and I’ll take you.”

Lilong wanted to allow herself a moment to exhale, to scream with joy and say, Finally, Lilong, you’re going home! She wanted to envision her daa’s face, pretend he was still alive (until she knew otherwise for sure). She wanted to imagine her siblings’ excitement when she returned with the Diwi in hand. She wanted to envision the Elder Warriors of the Abenai League patting her on the back for doing the right thing.

None of those things were going to happen. But that was not the reason for holding her breath.

She didn’t detest the Gaddo Company. She could even say she enjoyed working here. There was recreation, camaraderie, gifts like the kwaga. Two mooncycles in, Kubra bestowed upon her a “colony name,” which the company used in the field in lieu of one’s true name. (He named her Snakeblade—snake for her ability to, in his words, “shed skin,” and blade for her skillful ability with her short sword). It was a nice gesture, even though it was in keeping with the Code of Vagabonds—the loose list of rules of conduct by which every resident of the colony lived—which stated: Never inquire about a person’s past or their true name—a colony name and all the past they offer is sufficient. (Other rules: Stay within assigned territories; keep weaponry unconcealed at all times; company leadership must remain secret.)

Regardless, her impending journey east was an open secret. Traversing the Savanna Belt to the eastern coast where the Forest of the Mist lay would be a perilous task. There was a bounty on her head. Peace officers prowled the region. Bandits and wild beasts littered the open savanna. Even if she could somehow overcome these, there was the little matter of food, water, and reliable transport for the length of the trip, costly things she could not afford. She’d learned the hard way on her initial trip to Bassa that lacking these could kill you just as quickly as a sword.

So she’d requested a meeting with Gaddo to ask for help.

The Gaddo Company was one of the largest companies headquartered in Chabo, bigger than the Savanna Swine, Ravaging Mongrels, Tremor of the Sands, and other fledgling companies roaming the savanna but keeping base here. The Code of Vagabonds ensured that every company adhered to Chabo’s rules, but also served to strengthen the standing agreements between the companies and the law, which once consisted solely of vigilantes employed by Bassa-ordained warrant chiefs. But with peace officers now in the region, the warrant chiefs’ vigilantes no longer held as much sway—not even in Chugoko. The identities of company leadership were now at a premium. A headless group is a multi-headed one, Kubra had said, not as prone to decapitation.

So Lilong ended up never meeting Gaddo, despite working for them for a season and a half. But suddenly, out of the dust, an invitation?

“Tonight is not good,” said Lilong. “That is no time to prepare.”

“There’s nothing to prepare,” said Kubra. “They know all there is to know about you.”

Lilong eyed Kubra. “What have you gossiped?”

“Me, gossip?” Kubra chuckled. “Your suspicion knows no bounds, Snakeblade. You four need to keep an open mind until the meeting.”

Lilong lifted an eyebrow. “Us four?”

“Yes: you, the Whudans, the jali. Gaddo wants to meet you all.”

Lilong did not like the sound of that.

“And speaking of the jali,” Kubra continued, “can you tell him to stop distributing those tracts? We have better things to do than intercept hunthands.”

Lilong pursed her lips. “He is… going through some things.”

“Then he better go through them fast,” said Kubra. “Or one day, it will land in the hands of a peace officer who can read, and then we’ll all be doomed.”

Back at her quarters before the sky turned sunset orange, Lilong took the secret entrance—the rear one built of wood, made to look like an abandoned shack. She made straight for the washroom, wiped her sweaty parts, and switched back to her regular complexion before heading for the common area, praying that the evening dish would already be laid out. Sure enough, as she emerged from the darkness into the only room with windows not boarded shut, Biemwensé and Kakutan sat on short stools at the dwarf roundtable, surrounded by pounded yam, dika nut soup, and ram.

“Ooh, ram,” Lilong said, reaching for the bowl of meat. Biemwensé, without looking, stretched out her stick and smacked her hand before it reached the dish.

“Wait until your brother joins us,” she said.

Lilong massaged her smarting hand. She wasn’t sure if it was just a language thing, the way Biemwensé used brother to refer to Danso and auntie to herself and Kakutan. Other things she insisted upon: all four of them living in the same quarters; requiring everyone to be home before dusk; having the evening meal together. It was play-acting family, a fantasy, and Lilong hated it. Each had their own family, and this little gang of four was not it. Biemwensé herself never wasted an opportunity to speak about how much she missed her children, how much she wished she was back in Whudasha with her boys. Even Kakutan spoke often of returning to do right by the Whudans, gather them from every corner of the mainland and lead them back to safety.

Each had their own way of coping with the limbo they were stuck in, but Lilong’s patience for indulging them was wearing thin.

“Maybe you should tell brother,” Lilong said, “to stop leading bounty hunters here.”

Biemwensé pretended not to hear, instead resetting each dish in scalding water to keep the food warm. Lilong took the opportunity to snag one of the diced chunks of papaya lying in a side dish and stuffed it into her mouth.

Kakutan, transformed from Supreme Magnanimous to Chabo commoner by losing her warrior garb and cutting her hair short—part camouflage, part comfort, she’d say when asked—leaned in. “What happened?”

“I have good news and bad news,” said Lilong. “Pick.”

“Bad,” said Kakutan, at the same time Biemwensé said, “Good.”

“More hunthands who can read,” Lilong said, pulling out the yellowed tract seized from the men and slapping it on the table. “Mainlanders, these ones. I don’t know how this travelled all the way there.”

The women stared at the tract. Not that they needed to. As much as Danso denied it, everyone in this house knew it was him writing and distributing them.

Kakutan shook her head, saying, “Several times I’ve warned him. And yet.”

“Please don’t bring outside on my table,” said Biemwensé. With her stick, she shoved the tract onto the floor.

“He has to stop now,” said Lilong, “or all this hiding is for nothing.”

“Then tell him,” said Biemwensé. “He listens to you.”

Lilong shook her head. “Not anymore.”

Silence bit at them, interrupted only by Biemwensé’s impatient tapping of her stick.

“What’s the good news?” asked Kakutan.

“Meeting with Gaddo. Finally.”

The former Supreme Magnanimous sat up, flush across the face. “Say again?”

“Tonight. Kubra will take us.”

“Us?” Biemwensé said, at the same time Kakutan said, incredulously, “Tonight?”

Lilong nodded. “They want to meet with all of us.”

“Why?” asked Biemwensé. “You’re the one who needs help.”

“You are the ones going back to the mainland,” Lilong retorted.

“Right,” said Kakutan, rising. “Well, we can’t eat now! I hear meeting company leaders is like meeting royalty. I suspect there will be a hearty meal, and we cannot disrespect them by suggesting we’re full.”

“So what happens to all this?” Biemwensé gestured at the meal. “After I spent seasons preparing it?”

Kakutan shrugged. “We are sorry?”

“I can eat,” said Lilong, reaching for a bowl. Biemwensé’s stick came back up, but this time, Lilong was ready and caught it.

“What is wrong with you?” said Lilong. “You are not anybody’s maa here. Stop this.”

“Lilong,” said Kakutan, cocking her head. “Be gentle.” To Biemwensé, she said: “You know she’s right.” Then the former Supreme Magnanimous left it at that and went to prepare.

Biemwensé remained unfazed. “We all eat,” she said, strengthening her grip on the stick, “or no one does.”

Lilong slapped the stick away and left the room.

Danso was holed up in the dark, writing in his codex, when Lilong knocked and entered. He did not acknowledge her.

“You missed evening meal,” she said. “Biemwensé is upset.”

“Not hungry,” he said without looking up.

A beat, then she said: “We caught hunthands today. They had your tract.”

“Not my tract.”

Lilong collected herself. Be gentle.

“I know you are bursting with stories, and that you want to”—she put on his voice—“liberate people’s minds. But this actually hurts us.”

Danso said nothing. Lilong changed tack.

“Listen,” she said, stepping closer. “As a jali, I know this is the one power you have.” She did not mention the other power, the one he had forever abandoned and forbade her to speak of. “Your codex—its purpose is storytelling, yes? Tell all the stories you want in there. I promise you these tracts will not be missed. Nobody wants to hear the truth about Esheme—”

“Don’t say her name.”

Lilong held up her hands. “Fine. The Red Emperor.”

“Don’t say that either.”

Lilong scoffed. This was fruitless. “Look at us, arguing about names and tracts. We could be putting this time to better use. Like practicing with the Diwi.”

Danso stiffened. She hurried forward, giving him no time to respond.

“I have thought it through, Danso. We wrap ourselves up like I do on raids. No one recognises me out there, even when I do not skinchange—no one will be able to tell! We ride off to the outskirts, start out with the small critters—lizards, scorpions. Try bigger after.” She waved a hand over the scattered papers of his codex. “This isn’t the power that will save us if we come upon the emperor’s forces. Ibor is.”

Danso’s writing hand stopped moving. A shadow of a smile tugged at his lips.

“You have been practicing that argument.”

Lilong wrinkled her nose. “And what if so?”

“It’s a good argument.” He went back to writing. “But I told you. I’m not touching it again.”

Lilong exhaled, defeated. “Danso…”

He turned, anticipating the rest of her sentence. His hair, now moon-sized and unbraided, had not seen grooming in many mooncycles. His beard was the same, encroaching down his neck, moustache threatening to block his nostrils. His eyes were bloodshot from peering in the dark, refusing to light anything more than one candle.

What exactly are you going to say, Lilong? she thought. That she understood what it meant for one’s family, friends, home, livelihood—everything they loved, knew, and believed in—to be snatched away forever? Had she seen her daa murdered by her own intended’s hand? Had her closest associate been burned to a crisp right before her eyes? Had her sole actions broken the world and cost everything in the process?

She, too, had lost things, but not like this. It had to be hard, living every day knowing he escaped Bassa’s grip, but everyone else he cared about was still trapped there: friends, uncles, mentors. Had to be hard knowing he could do little or nothing to help them—not even with stories, the one thing he was good at. And how could he save them if he wasn’t safe, if he couldn’t even go outside without a disguise?

At least everyone under this roof had something to look forward to, a people to return to, no matter how fractured the situation. Danso had nothing.

So what did she really know about what he was going through?

“Never mind you,” she said. “I just came to give the news.”

This made him perk up. He put down his charcoal stylus and gave her his undivided attention.

“We have the meeting. Tonight.”

His eyes lit up. “Gaddo?” She nodded. “All of us?” She nodded again.

“The aunties want you to… make yourself proper.”

“Ah,” he said, then chuckled. She hadn’t heard that sound in a while.

“So, this is real?” A small vigor had crept back into his once-defeated manner. “We’re going home?”

He said home like the Ihinyon islands were theirs to share. Maybe they were. Agreeing to come east with her was the right choice, seeing as he had nowhere left of his own. Perhaps it wasn’t a bad idea to start thinking of Namge as home. And who knew? Maybe the seven islands might be more welcoming than she envisaged.

Chabo

Fifth Mooncycle, same day

MEETING GADDO WAS INDEED like meeting royalty. Now that company leaders were only learned of by word of mouth, tales about them abounded, each trying to outdo the others through exaggeration. Lilong doubted the commander of the Tremor of the Sands had ever slain a lion with his bare hands, or the matriarch of the Savanna Swine truly descended from a desertland goddess of war. Such tales were primarily to instil fear into merchants who were unlucky enough to encounter their companies.

Of Gaddo, the songs were more realist. No one had seen enough to tell if they were man or woman or neither or both. While every other company leader was a fugitive of some sort, Gaddo was best at disguises, hiding in plain sight, and therefore had never been caught or imprisoned. Lilong knew it was a huge feat to orbit the savanna in this way yet remain anonymous, so she was equal parts curious and anxious about this meeting.

Kubra took the party of four on a trek through an extensive thicket, one of the last few of such still standing in the desertlands. Chabo boasted a couple only due to its closeness to the coast.

“You’d think that weeks in the Breathing Forest would make me less uneasy about walking into forests at night,” Danso, beard and hair now trimmed, whispered to Lilong as they went deeper and deeper into the thicket. “But look.” He stretched out trembling hands.

“Kubra cannot harm us,” Lilong whispered back.

Danso appraised the man, who was walking in front of the Whudan women.

“I wouldn’t know,” he said. “He and his employers are still blank slates to me.”

Lilong shrugged. “Do we have a choice?”

Kubra meandered some more, holding a lantern up, until they finally arrived at a dense wall of vines. He handed the lantern to Kakutan and pulled the vines apart. Behind them was a sturdy wall built with slender trunks, disguised as trees by greenery tied to the top of them. Kubra led them in, squeezing through some space, and they finally arrived at a tunnel-like opening. They trudged forward, toward light streaming in from the opposite opening.

A scent wafted over to greet them.

“Is that—” Danso started.

“Bean pudding?” Lilong said.

“We call it moi-moi here,” Kubra said. “Come, let me show you.”

They emerged from the opposite end into a clearing, and it was all Lilong could do to keep from gasping.

Before them was a garden, set into the mist of night. Lanterns hung from branches and cast soft glows on flowers arranged in various patterns. At the centre of it all was a large hut—couldn’t call it a hut, really, because it was too large, but it was built to look like one anyway. The grass was soft and inviting, meticulously tended to. Off to a side was a tiny patch of farm with various plants growing. In that farm were two figures: a woman, holding up an open-flame lamp, and a man, bent over and picking some fruit from a shrub.

“They are here,” Kubra announced.

Both figures rose as one, and the woman lifted the lamp to show their faces. They were both elderly—Lilong surmised them to be about the same age as Biemwensé. The woman—mainlander, high-black as humus—had a permanent warm smile affixed to her face in a way that uneased Lilong. The man—low-brown, desertlander—presented as aloof, as if only just remembering people existed outside of the woman next to him, and Lilong couldn’t decide if this was a front or not. He rubbed the fruits he had been picking up—yellow lantern peppers—in his palm.

“Welcome, dear ones,” the woman said in crisp High Bassai. “Please, have a seat.” She waved them toward open space outside the hut, mats spread over the soft grass. To Kubra, she said, in Savanna Common: “You may guard the entrance.”

Kubra went over to do just that. The party remained standing, confused. When no one else seemed willing to ask the obvious question, Lilong blurted out: “Is it you we are supposed to meet?”

“Ah,” the woman said, dusting her palms together and interlinking her arm with the man—Lilong assumed they were some sort of partners. They made their way over to the group.

“You must be Lilong,” the woman said, the smile still plastered on her face. “The Snakeblade.”

“And skinchanger, don’t forget.” The man had a shrill voice, as if he was perpetually excited. “Also: extraordinary Ihinyon warrior.”

Lilong frowned. Kubra had been right. They knew a lot.

“We take it upon ourselves to know everyone who works for us,” the woman said. She pointed at Danso. “You’re the scholar—my apologies, jali, yes? And you”—she pointed to Kakutan—“must be the Supreme Magnanimous of Whudasha. Well, former Supreme Magnanimous.” She looked Biemwensé over. “And you’re the one we’re still trying to piece together.”

The Whudan women glanced at each other. Danso, the only person who seemed pleased to be recognised, offered a wry smile.

“Jali novitiate,” he corrected. “But I was close to graduating.”

Lilong offered nothing, turning things over in her mind. She had expected to be recognised, sure, but these people did not even refer to the seven islands as Nameless like everyone else. They had used their real name.

“So you are… Gaddo?” asked Kakutan.

“As we live and breathe,” the man said. “You may call me Pa Gaddo. This here is Ma Gaddo.”

“And those are your real names?”

The two looked at one another and smiled.

“Real enough for our purposes,” said Ma Gaddo.

“So there are two of you,” Danso added. “And, you are…”

“Old? Not warriors? Warm and welcoming?” Pa Gaddo said.

“From opposite sides of the border?” Ma Gaddo said.

Lilong was wary of people who answered questions before you asked them.

“There is nothing to be said about us that we haven’t heard. Come, sit.” Pa Gaddo placed the lantern peppers in Ma Gaddo’s hand. “Let us spice up that moi-moi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...