- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

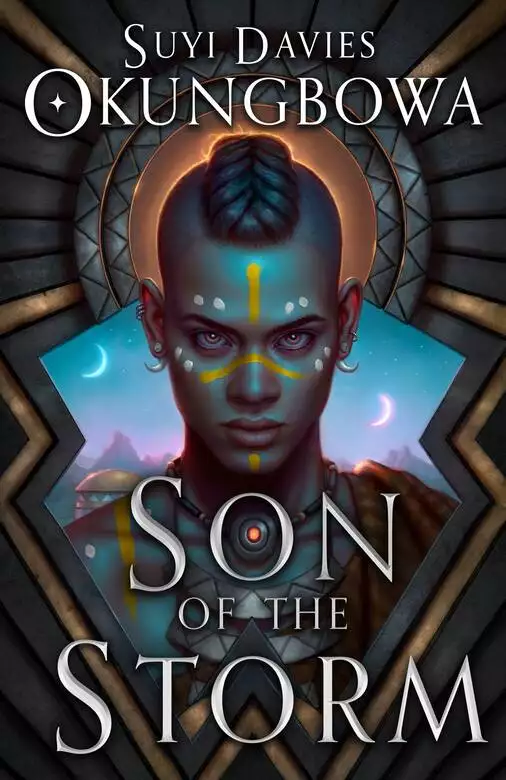

Synopsis

'A vibrant tale of betrayal, intrigue and revolution' Anthony Ryan

'A thrilling, fantastical adventure that introduces a beguiling new world' S. A. Chakraborty

In the city of Bassa, Danso is a clever scholar on the cusp of achieving greatness-only he doesn't want it. Instead, he prefers to chase forbidden stories about what lies outside the city walls. The Bassai elite claim there is nothing of interest. The city's immigrants are sworn to secrecy.

But when Danso stumbles across a warrior wielding magic that shouldn't exist, he's put on a collision course with Bassa's darkest secrets. Drawn into the city's hidden history, he sets out on a journey beyond its borders. But the chaos left in the wake of his discovery threatens to destroy the empire.

Award-winning author Suyi Davies Okungbowa begins a thrilling new epic fantasy series of violent conquest, buried histories and forbidden magic.

Praise for Son of the Storm

'A contender for best new fantasy series of the year' SFX

'Everything I love to see in a fantasy story: masterful, fully-realised worldbuilding, morally complex characters, thoughtful and piercing interrogations of power . . . Damn good stuff!' Jenn Lyons

'An elaborately plotted tale of ancient magics and world-shattering politics. I, like many others, will be impatiently waiting for the next instalment!' Andrea Stewart

'An original and fully conceived new world of fantasy teeming with brilliant possibilities' P. Djèlí Clark

'An epic fantasy set apart by how deftly Okungbowa unfurls his intricate, richly imagined world' A. K. Larkwood

'Forgotten magic propels a richly drawn story of ambition, conspiracy and the elusiveness of belonging' Fonda Lee

'Bold characters, bloody action and brutal politics. I thoroughly enjoyed it!'

James Islington

Release date: May 11, 2021

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Son of the Storm

Suyi Davies Okungbowa

For a multitude of seasons before Oke was born, the travelhouse had offered food, wine, board, and music—and for those who had been on the road too long, companionship—to many a traveller across the Savanna Belt. Its patronage consisted solely of those who lugged loads of gold, bronze, nuts, produce, textile, and craftwork from Bassa into the Savanna Belt or, for the even more daring, to the Idjama desert across Lake Vezha. On their way back, they would stop at the caravansary again, the banana and yam and rice loads on their camels gone and now replaced with tablets of salt, wool, and beaded ornaments.

But there was another set of people for whom the caravansary stood, those whose sights were set on discovering the storied isthmus that connected the Savanna Belt to the yet-to-be-sighted seven islands of the archipelago. For people like these, the Weary Sojourner stood as something else: a vantage point. And for people like Oke who had a leg in all three worlds, walking into the Weary Sojourner called for an intensified level of alertness.

Especially when the fate of the three worlds could be determined by the very meeting she was going to have.

She swung open the curtain. She did not push back her cloak.

Like many public houses in the Savanna Belt, the Weary Sojourner operated in darkness, despite it being late morning. During her time in the desertlands, Oke had learned that this was a practice carried over from the time of the Leopard Emperor when liquor was banned in its desert protectorates, and secret houses were operated under the cover of darkness. Even though that period of despotism was thankfully over, habitual practices were difficult to shake off. People still preferred to drink and smoke and fuck in the dark.

Which made this the perfect place for Oke’s meeting.

She took a seat at the back and surveyed the room. It was at once obvious that her contact wasn’t around. There were exactly three people here, all men who had clearly just arrived from the same caravan. Their clothes gave them away: definitely Bassai, in brightly coloured cotton wrappers, bronze jewellery—no sensible person travelled with gold jewellery—over some velvet, wool, and leatherskin boots for the desert’s cold. Senior members of the merchantry guild, looking at that velvet. Definitely members of the Idu, the mainland’s noble caste. Guild aside, their complexions also gave that away—high-black skin, as dark as the darkest of humuses, just the way Bassa liked it. It was the kind of complexion she hadn’t seen in a long time.

Oke swept aside a nearby curtain and looked outside. Sure enough, there was their caravan, parked behind the establishment, guarded by a few private Bassai hunthands. Beside them, travelhands—hired desert immigrants to the mainland judging by their complexions, what the Bassai would refer to as low-brown for how light and lowly it was—unpacking busily for an overnight stay and unsaddling the camels so they could drink. There were no layers of dust on anyone yet, so clearly they were northbound.

“A drink, maa?”

Oke looked up at the housekeep, who had come over, wringing his hands in a rag. She could see little of his face, but she had been here twice before, and knew enough of what he looked like.

“Palm wine and jackalberry with ginger,” she said, hiding her hands.

The housekeep stopped short. “Interesting choice of drink.” He peered closer. “Have you been here before?” He enunciated the words in Savanna Common in a way that betrayed his border origins.

Oke’s eyes scanned him and decided he was asking this innocently. “Why do you ask?”

“You remember things, as a housekeep,” he said, leaning back on a nearby counter. “Especially drink combinations that join lands that have no place joining.”

“Consider it an acquired taste,” Oke said, and looked away, signalling the end of the discussion. But to her surprise, the man nodded at the group far away and asked, in clear Mainland Common:

“You with them?”

Oke froze. He had seen her complexion, then, and knew enough to know she had mainland origins. What had always been a curse for Oke back when she was a mainlander—Too light, is she punished by Menai? people would ask her daa—had become a gift in self-exile over the border. But there were a few people with keen eyes and ears who would, every now and then, recognise a lilt in her Savanna Common or note how her hair curled a bit too tightly for a desertlander or how she carried herself with a smidgen of mainlander confidence. There was only one way to react to that, as she always did whenever this came up.

“What?” She frowned. “Sorry, I don’t understand that language.”

The housekeep eyed her for another moment, then went away.

Oke breathed a sigh of relief. It was of the utmost importance that no one knew who she was and what she was doing here, living in the Savanna Belt. Because the history of the Savanna Belt was what it was, a tiny enough number of people who originated from this side of the Soke border looked just a bit like she did. Passing as one was easier once she perfected the languages. Thank moons she had studied them as a scholar in Bassa.

She drank slowly once the housekeep brought her order, and she put forward some cowries, making sure to add a few pieces to clearly signal she wanted to be left alone.

Halfway through her drink, she realised her contact was running late. She looked outside again. The sky had gone cloudy, and the sun was missing for a while. She went back to her drink and nursed it some more.

The men in the room rose and went up to be shown to their rooms. Oke peeked out of the curtain again. The travelhands were gone. One hunthand stood and guarded the caravan. One stood at the back door to the caravansary. The camels still stood there, lapping water.

Oke ordered another drink and waited. The sun came back out. It was past an hour now. She looked out again. The camels had stopped drinking and now lay in the dust, snoozing.

Something was wrong.

Oke got up without touching her new drink, put down some more cowries on the counter in front of the housekeep, and walked to the front door of the caravansary. On second thought, she turned and went back to the housekeep.

“Your alternate exit. Show me.”

The man pointed without looking at her. Oke took it and went around the building, evading both the men and the animals. She eventually showed up to where she had left her own animal—a kwaga, a striped beauty with tiny horns. She untied and patted it. It snorted in return. Then she slapped its hindquarters and set it off on a run, barking as it went.

She waited for a moment or two, then dashed away herself.

Going through a secluded route on foot, while trying to stay as nondescript as possible, took a long time. Oke had to take double the usual precautions, as banditry had increased so much on the trade routes that one was more likely to get robbed and murdered than not. Back when Bassa was Bassa—not now with its heavily diluted population and generally weakening influence—no one would dare attack a Bassai caravan anywhere on the continent for fear of retaliation. These days, every caravan had to travel with private security. The Bassai Upper Council was well known for being toothless and only concerned with enriching themselves.

The clouds from earlier had disappeared, and the sun beat mercilessly on her, causing her to sweat rivers beneath her cloak, but Oke knew she had done the right thing. It was as they had agreed: If either of them got even a whiff of something off, they were to make a getaway as swiftly as possible. She was then to head straight for the place nicknamed the Forest of the Mist, the thick, uncharted woodland with often heavy fog that was storied to house secret passages to an isthmus that connected the Savanna Belt to the seven islands of the eastern archipelago.

It didn’t matter any longer if that bit of desertland myth was true or not. Whether the archipelago even still existed was moot at this point. The yet undiscovered knowledge she had gleaned from her clandestine exploits in the library at the University of Bassa, coupled with the artifacts her contact was bringing her—if either made it into the wrong hands, the whole continent of Oon would pay for it. Oke wasn’t ready to drop the fate of the continent in the dust just yet.

Two hours later, Oke looked back and saw in the sky the grey tip of what she knew came from thick, black smoke. Not the kind of smoke that came from a nearby kitchen, but the kind that said something far away had been destroyed. Something big.

She took a detour in her journey and headed for the closest high point she knew. She chose one that overlooked a decent portion of the savanna but also kept her on the way to the Forest of the Mist. It took a while to ascend to the top, but she soon got to a good enough vantage point to look across and see the caravansary.

The Weary Sojourner stuck out like an anthill, the one establishment for a distance where the road from the border branched into the Savanna Belt. The caravansary was up in flames. It was too far for her to see the people and animals, but she knew what those things scattering from the raging inferno were. The body language of disaster was the same everywhere.

Oke began to descend fast, her chest weightless. The Forest of the Mist was the only place on this continent where she would be safe now, and she needed to get there immediately. Whoever set that fire to the Weary Sojourner knew who she and her contact were. Her contact may or may not have made it out alive. It was up to her now to ensure that the continent’s biggest secret was kept that way.

The alternative was simply too grave to consider.

THE RUMOURS BROKE SLOWLY but spread fast, like bushfire from a raincloud. Bassa’s central market sparked and sizzled, as word jumped from lip to ear, lip to ear, speculating. The people responded minimally at first: a shift of the shoulders, a retying of wrappers. Then murmurs rose, until they matured into a buzzing that swept through the city, swinging from stranger to stranger and stall to stall, everyone opening conversation with whispers of Is it true? Has the Soke Pass really been shut down?

Danso waded through the clumps of gossipers, sweating, cursing his decision to go through the central market rather than the mainway. He darted between throngs of oblivious citizens huddled around vendors and spilling into the pathway.

“Leave way, leave way,” he called, irritated, as he shouldered through bodies. He crouched, wriggling his lean frame underneath a large table that reeked of pepper seeds and fowl shit. The ground, paved with baked earth, was not supposed to be wet, since harmattan season was soon to begin. But some fool had dumped water in the wrong place, and red mud eventually found a way into Danso’s sandals. Someone else had abandoned a huge stack of yam sacks right in the middle of the pathway and gone off to do moons knew what, so that Danso was forced to clamber over yet another obstacle. He found a large brown stain on his wrappers thereafter. He wiped at the spot with his elbow, but the stain only spread.

Great. Now not only was he going to be the late jali novitiate, he was going to be the dirty one, too.

If only he could’ve ridden a kwaga through the market, Danso thought. But markets were foot traffic only, so even though jalis or their novitiates rarely moved on foot, he had to in this instance. On this day, when he needed to get to the centre of town as quickly as possible while raising zero eyebrows, he needed to brave the shortest path from home to city square, which meant going through Bassa’s most motley crowd. This was the price he had to pay for missing the city crier’s call three whole times, therefore setting himself up for yet another late arrival at a mandatory event—in this case, a Great Dome announcement.

Missing this impromptu meeting would be his third infraction, which could mean expulsion from the university. He’d already been given two strikes: first, for repeatedly arguing with Elder Jalis and trying to prove his superior intelligence; then more recently, for being caught poring over a restricted manuscript that was supposed to be for only two sets of eyes: emperors, back when Bassa still had them, and the archivist scholars who didn’t even get to read them except while scribing. At this rate, all they needed was a reason to send him away. Expulsion would definitely lose him favour with Esheme, and if anything happened to their intendedship as a result, he could consider his life in this city officially over. He would end up exactly like his daa—a disgraced outcast—and Habba would die first before that happened.

The end of the market pathway came within sight. Danso burst out into mainway one, the smack middle of Bassa’s thirty mainways that crisscrossed one another and split the city perpendicular to the Soke mountains. The midday sun shone brighter here. Though shoddy, the market’s thatch roofing had saved him from some of the tropical sun, and now out of it, the humid heat came down on him unbearably. He shaded his eyes.

In the distance, the capital square stood at the end of the mainway. The Great Dome nestled prettily in its centre, against a backdrop of Bassai rounded-corner mudbrick architecture, like a god surrounded by its worshippers. Behind it, the Soke mountains stuck their raggedy heads so high into the clouds that they could be seen from every spot in Bassa, hunching protectively over the mainland’s shining crown.

What took his attention, though, was the crowd in the mainway, leading up to the Great Dome. The wide street was packed full of mainlanders, from where Danso stood to the gates of the courtyard in the distance. The only times he’d seen this much of a gathering were when, every once in a while, troublemakers who called themselves the Coalition for New Bassa staged protests that mostly ended in pockets of riots and skirmishes with Bassai civic guards. This, however, seemed quite nonviolent, but that did nothing for the air of tension that permeated the crowd.

The civic guards at the gates weren’t letting anyone in, obviously—only the ruling councils; government officials and ward leaders; members of select guilds, like the jali guild he belonged to; and civic guards themselves were allowed into the city centre. It was these select people who then took whatever news was disseminated back to their various wards. Only during a mooncrossing festival were regular citizens allowed into the courtyard.

Danso watched the crowd for a while to make a quick decision. The thrumming vibe was clearly one of anger, perplexity, and anxiety. He spotted a few people wailing and rolling in the dusty red earth, calling the names of their loved ones—those stuck outside the Pass, he surmised from their cries. Since First Ward was the largest commercial ward in Bassa, businesses at the sides of the mainway were hubbubs of hissed conversation, questions circulating under breaths. Danso caught some of the whispers, squeaky with tension: The drawbridges over the moats? Rolled up. The border gates? Sealed, iron barriers driven into the earth. Only a ten-person team of earthworkers and ironworkers can open it. The pace of their speech was frantic, fast, faster, everyone wondering what was true and what wasn’t.

Danso cut back into a side street that opened up from the walls along the mainway, then cut into the corridors between private yards. Up here in First Ward, the corridors were clean, the ground was of polished earth, and beggars and rats did not populate here as they did in the outer wards. Yet they were still dark and largely unlit, so that Danso had to squint and sometimes reach out to feel before him. Navigation, however, wasn’t a problem. This wasn’t his first dance in the mazy corridors of Bassa, and this wasn’t the first time he was taking a shortcut to the Great Dome.

Some househands passed by him on their way to errands, blending into the poor light, their red immigrant anklets clacking as they went. These narrow walkways built into the spaces between courtyards were natural terrain for their caste—Yelekuté, the lower of Bassa’s two indentured immigrant castes. The nation didn’t really fancy anything undesirable showing up in all the important places, including the low-brown complexion that, among other things, easily signified desertlanders. The more desired high-brown Potokin were the chosen desertlanders allowed on the mainways, but only in company of their employers.

Ordinarily, they wouldn’t pay him much attention. It wasn’t a rare sight to spot people of other castes dallying in one backyard escapade or another. But today, hurrying past and dripping sweat, they glanced at Danso as he went, taking in his yellow-and-maroon tie-and-dye wrappers and the fat, single plait of hair in the middle of his head, the two signs that indicated he was a jali novitiate at the university. They considered his complexion—not dark enough to be wearing that dress in the first place; hair not curled tightly enough to be pure mainlander—and concluded, decided, that he was not Bassai enough.

This assessment they carried out in a heartbeat, but Danso was so used to seeing the whole process happen on people’s faces that he knew what they were doing even before they did. And as always, then came the next part, where they tried to put two and two together to decide what caste he belonged to. Their confused faces told the story of his life. His clothes and hair plait said jali novitiate, that he was a scholar-historian enrolled at the University of Bassa, and therefore had to be an Idu, the only caste allowed to attend said university. But his too-light complexion said Shashi caste, said he was of a poisoned union between a mainlander and an outlander and that even if the moons intervened, he would always be a disgrace to the mainland, an outcast who didn’t even deserve to stand there and exist.

Perhaps it was this confusion that led the househands to go past him without offering the requisite greeting for Idu caste members. Danso snickered to himself. If belonging to both the highest and lowest castes in the land at the same time taught one anything, it was that when people had to choose where to place a person, they would always choose a spot beneath them.

He went past more househands who offered the same response, but he paid little heed, spatially mapping out where he could emerge closest to the city square. He finally found the exit he was looking for. Glad to be away from the darkness, he veered into the nearest street and followed the crowd back to the mainway.

The city square had five iron pedestrian gates, all guarded. To his luck, Danso emerged just close to one, manned by four typical civic guards: tall, snarling, and bloodshot-eyed. He made for it gleefully and pushed to go in.

The nearest civic guard held the gate firmly and frowned down at Danso.

“Where you think you’re going?” he asked.

“The announcement,” Danso said. “Obviously.”

The civic guard looked Danso over, his chest rising and falling, his low-black skin shiny with sweat in the afternoon heat. Civic guards were Emuru, the lower of the pure mainlander caste, but they still wielded a lot of power. As the caste directly below the Idu, they could be brutal if given the space, especially if one belonged to any of the castes below them.

“And you’re going as what?”

Danso lifted an eyebrow. “Excuse me?”

The guard looked at him again, then shoved Danso hard, so hard that he almost fell back into the group of people standing there.

“Ah!” Danso said. “Are you okay?”

“Get away. This resemble place for ruffians?” His Mainland Common was so poor he might have been better off speaking Mainland Pidgin, but that was the curse of working within proximity of so many Idu: Speaking Mainland Pidgin around them was almost as good as a crime. Here in the inner wards, High Bassai was accepted, Mainland Common was tolerated, and Mainland Pidgin was punished.

“Look,” Danso said. “Can you not see I’m a jali novi—”

“I cannot see anything,” the guard said, waving him away. “How can you be novitiate? I mean, look at you.”

Danso looked over himself and suddenly realised what the man meant. His tie-and-dye wrappers didn’t, in fact, look like they belonged to any respectable jali novitiate. Not only had he forgotten to give them to Zaq to wash after his last guild class, the market run had only made them worse. His feet were dusty and unwashed; his arms, and probably face, were crackled, dry, and smeared with harmattan dust. One of his sandal straps had pulled off. He ran a hand over his head and sighed. Experience should have taught him by now that his sparser hair, much of it inherited from his maternal Ajabo-islander side, never stayed long in the Bassai plait, which was designed for hair that curled tighter naturally. Running around without a firm new plait had produced unintended results: Half of it had come undone, which made him look unprepared, disrespectful, and not at all like any jali anyone knew.

And of course, there had been no time to take a bath, and he had not put on any sort of decent facepaint either. He’d also arrived without a kwaga. What manner of jali novitiate walked to an impromptu announcement such as this, and without a Second in tow for that matter?

He should really have listened for the city crier’s ring.

“Okay, wait, listen,” Danso said, desperate. “I was late. So I took the corridors. But I’m really a jali novitiate.”

“I will close my eye,” the civic guard said. “Before I open it, I no want to see you here.”

“But I’m supposed to be here.” Danso’s voice was suddenly squeaky, guilty. “I have to go in there.”

“Rubbish,” the man spat. “You even steal that cloth or what?”

Danso’s words got stuck in his throat, panic suddenly gripping him. Not because this civic guard was an idiot—oh, no, just wait until Danso reported him—but because so many things were going to go wrong if he didn’t get in there immediately.

First, there was Esheme, waiting for him in there. He could already imagine her fuming, her lips set, frown stuck in place. It was unheard of for intendeds to attend any capital square gathering alone, and it was worse that they were both novitiates—he of the scholar-historians, she of the counsel guild of mainland law. His absence would be easily noticed. She had probably already sat through most of the meeting craning her neck to glance at the entrance, hoping he would come in and ensure that she didn’t have to suffer that embarrassment. He imagined Nem, her maa, and how she would cast him the same dissatisfied look as when she sometimes told Esheme, You’re really too good for that boy. If there was anything his daa hated, it was disappointing someone as influential as Nem in any way. He might be of guild age, but his daa would readily come for him with a guava stick just for that, and his triplet uncles would be like a choir behind him going Ehen, ehen, yes, teach him well, Habba.

His DaaHabba name wouldn’t save him this time. He could be prevented from taking guild finals, and his whole life—and that of his family—could be ruined.

“I will tell you one last time,” the civic guard said, taking a step toward Danso so that he could almost smell the dirt of the man’s loincloth. “If you no leave here now, I will arrest you for trying to be novitiate.”

He was so tall that his chest armour was right in Danso’s face, the branded official emblem of the Nation of Great Bassa—the five ragged peaks of the Soke mountains with a warrior atop each, holding a spear and runku—staring back at him.

He really couldn’t leave. He’d be over, done. So instead, Danso did the first thing that came to mind. He tried to slip past the civic guard.

It was almost as if the civic guard had expected it, as if it was behaviour he’d seen often. He didn’t even move his body. He just stretched out a massive arm and caught Danso’s clothes. He swung him around, and Danso crumpled into a heap at the man’s feet.

The other guards laughed, as did the small group of people by the gate, but the civic guard wasn’t done. He feinted, like he was about to lunge and hit Danso. Danso flinched, anticipating, protecting his head. Everyone laughed even louder, boisterous.

“Ei Shashi,” another civic guard said, “you miss yo way? Is over there.” He pointed west, toward Whudasha, toward the coast and the bight and the seas beyond them, and everyone laughed at the joke.

Every peal was another sting in Danso’s chest as the word pricked him all over his body. Shashi. Shashi. Shashi.

It shouldn’t have gotten to him. Not on this day, at least. Danso had been Shashi all his life, one of an almost nonexistent pinch in Bassa. He was the first Shashi to make it into a top guild since the Second Great War. Unlike every other Shashi sequestered away in Whudasha, he was allowed to sit side by side with other Idu, walk the nation’s roads, go to its university, have a Second for himself, and even be joined to one of its citizens. But every day he was always reminded, in case he had forgotten, of what he really was—never enough. Almost there, but never complete. That lump should have been easy to get past his throat by now.

And yet, something hot and prideful rose in his chest at this laughter, and he picked himself up, slowly.

As the leader turned away, Danso aimed his words at the man, like arrows.

“Calling me Shashi,” Danso said, “yet you want to be me. But you will always be less than bastards in this city. You can never be better than me.”

What happened next was difficult for Danso to explain. First, the civic guard turned. Then he moved his hand to his waist where his runku, the large wooden club with a blob at one end, hung. He unclipped its buckle with a click, then moved so fast that Danso had no time to react.

There was a shout. Something hit Danso in the head. There was light, and then there was darkness.

Danso awoke to a face peering at his. It was large, and he could see faint traces left by poorly healed scars. A pain beat in his temple, and it took a while for the face to come into full focus.

Oboda. Esheme’s Second.

The big man stood up, silent. Oboda was a bulky man with just as mountainous a presence. Even his shadow took up space, so much so that it shaded Danso from the sunlight. The coral pieces embedded into his neck, in a way no Second that Danso knew ever had, glinted. He didn’t even wear a migrant anklet or anything else that announced that he was an immigrant. The only signifier was his complexion: just dark enough as a desertlander to be acceptably close to the Bassai Ideal’s yardstick—the complexion of the humus, that which gave life to everything and made it thrive. Being high-brown while possessing the build and skills of a desert warrior put him squarely in the higher Potokin caste. Oboda, as a result, was allowed freedoms many immigrants weren’t, so he ended up being not quite Esheme’s or Nem’s Second, but something more complex, something that didn’t yet have a name.

Danso blinked some more. The capital square behind Oboda was filled, but now with a new crowd, this one pouring out of the sectioned entryway arches of the Great Dome and heading for their parked travelwagons, kept ready by various househands and stablehands. Wrappers of various colours dotted the scene before him, each council or guild representing itself properly. He could already map out those of the Elders of the merchantry guild in their green and gold combinations, and Elders of other guilds in orange, blue, bark, violet, crimson. There were even a few from the university within sight, scholars and jalis alike, in their white robes.

Danso shrunk into Oboda’s shadow, obscuring himself. It would be a disaster for them to see him like this. It would be a disaster for anyone to see him so. But then, he thought, if Oboda is here, that means Esheme…

“Danso,” a woman’s voice said.

Oh moons!

Delicately, Esheme gathered her clothes in the crook of one arm and picked her way toward him. She was dressed in tie-and-dye wrappers just like his, but hers were of different colours—violet dappled in orange, the uniform for counsel novitiates of mainland law—and a far cry from his: Hers were washed and dipped in starch so that they shone and didn’t even flicker in the breeze.

As she came forward, the people who were starting to gather to watch the scene gazed at her with wide-eyed appreciation. Esheme was able to do that, elicit responses from everything and everyone by simply being. She knew exactly how to play to eyes, knew what to do to evoke the exact reactions she wanted from people. She did so now, swaying just the right amount yet keeping a regal posture so that she was both desirable and fearsome at once. The three plaited arches on her head gleamed in the afternoon sun, the deep-yellow cheto dye massaged into her hair illuminating her head. Her high-black complexion, dark and pure in the most desirable Bassai way, shone with superior fragrant shea oils. She had her gaze squarely on Danso’s face so that he couldn’t look at her, but had to look down.

She arrived where he sat, took one sweeping look at the civic guards, and said, “What happened here?”

“I was trying to attend the announcement and this one”—Danso pointed at the nearby offending civic guard—“hit

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...