- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

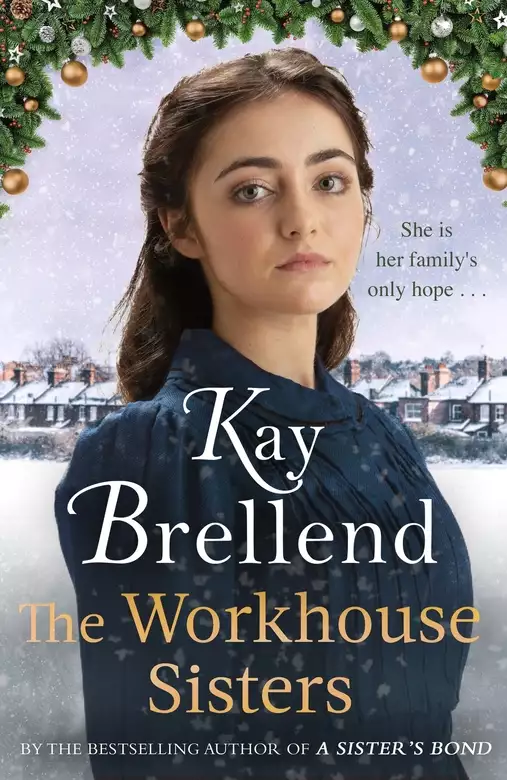

Synopsis

After escaping the grip of the workhouse, Lily has kept her fiance's business afloat while he is away fighting on the Western Front. Still battling on, she's now doing her bit for her country as an auxiliary nurse - but one thing above all else continues to weigh heavily on her heart: her long-lost sister. Born just before her mother died, the scandal was hushed-up and the baby spirited away. But now, at last, there is hope Lily could find her little sister for she has a clue to go on: the name of the notorious baby farmer who bought the child all those years ago. Mrs Jolley. Using all her pluck, and with the help of her two friends Margie and Fanny, Lily will do anything in her power to find her little sister and save her from the dark streets of London.

With winter drawing in, and the war with no end in sight, will she be able to bring her family together?

Release date: February 3, 2022

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 100000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Workhouse Sisters

Kay Brellend

Whitechapel Workhouse, Mile End Road, East London

‘Merry Christmas, my dear.’

Having poured two large measures of Scotch, the fellow handed one to his companion and raised his own in a toast. Firelight glinted through their chinking glasses, tinting the whisky ruby red. ‘And here’s to a very happy 1916. God willing, this war will finally come to an end.’ He sipped, smacked his lips, then sank into a hearthside armchair, sighing contentedly.

‘Never mind the bloomin’ war.’ His friend downed her drink in two unladylike glugs. ‘It would be better still if my husband popped his clogs before spring.’ She winked. ‘We could get married. After a decent time, that is. Not that Bill Gladwell deserves much respect or grieving, the way he’s treated me over the years.’ She perched on the arm of his chair. ‘We could retire to the coast, eh, love?’ She dropped a kiss on her boyfriend’s balding crown, her salt-and-pepper ringlets curtaining his jowls.

Norman Drake smiled gamely, though he wasn’t intending to marry again. He was fond of his lady friend, but he’d no wish for another wife. One had been enough and his heart was buried in her grave. She’d passed away almost a decade ago and he had kept busy to stop himself pining. His employment left scant free time, and he’d adapted to his living arrangements. He had a cosy little domain: private, yet well situated, if he chose to immerse himself in East End hubbub. Occasionally he did when he had a day off, and would browse the teeming markets and join in the pub sing-songs. But he was content with his own company and found a weekly visit or two from his companion to be sufficient.

June Gladwell was an old friend of his late wife’s, the two of them having grown up together in the backstreets of Whitechapel. June was a lusty woman and was up for a romp when the mood took them . . . which wasn’t as often as when they had first become a couple. They were both in their early sixties, though June was still youthful in body and mind. Norman hadn’t aged as well and was feeling his years. He had arthritis that gave him gyp in the winter months. More worrying were the pains in his chest that came and went. No amount of liniment soothed those.

He tipped his glass and another warming swig of whisky slid down his throat. He rubbed his aching knees, moving his slippers towards the warmth in the grate.

June helped herself to the dregs in the whisky bottle and swiftly dispatched them. She ambled to and fro in front of the fire, the empty tumbler oscillating between thumb and fingers. It was Christmas Eve and she’d dressed up in her glad rags, hoping to persuade Norman to take her out.

‘Sit down . . . you’re making me giddy, June,’ he complained.

She did take the seat opposite but tapped her feet like a fidgety child. She felt exuberant and didn’t want to waste time cooped up in this dreary place. Her glass found the table with a thud. Christmas Eve was for celebrating and she wanted to get tipsy and have fun. There was little enough enjoyment in her life, stuck, as she was, in three ground-floor rooms of a rotten terrace, with a crippled husband. She was sure Bill was clinging to his miserable existence just to spite her. Last time he’d been admitted to the London Hospital in Whitechapel the doctor had told her she must prepare for him never to come home. But he had. Drat him.

She flopped back in her chair with an exaggerated sigh. Norman looked older than his age and acted it, too. He seemed ready to doze off, not have a knees-up. The least he could do was break open another bottle of Scotch, or there’d be little point in her hanging around. She wasn’t settling for toasting her toes by a Yuletide fire without a drink in her hand. She could go and meet her neighbours in the pub and belt out carols round the piano. She’d heard the raucous choir when walking along the Mile End Road and had been tempted to go inside and join the carousers, glimpsed through the frosted glass.

‘Thanks for the drink then.’ She flounced to her feet. ‘You seem all in, ducks, so I’ll say toodle-oo and let you have a little kip. I’ll call again after Boxing Day, I expect.’

Norman started from his doze. It was difficult to keep his eyes open with flames doing a hypnotic dance about the logs. He didn’t fancy being on his own on this special night so stirred himself. June was reaching for the feathered hat she’d taken off earlier and dropped on the table.

‘Don’t go yet, love. There’s more tiddly in the sideboard.’ He eased himself out of the chair. ‘I was saving a few brown ales for tomorrow.’

‘Why don’t we go to the pub?’ she countered. ‘We can get properly merry. The company will do you good. You’re stuck in this place too often.’ June wasn’t settling for a bottle of lousy beer. She wanted port or whisky, and her glass refilled several times.

‘I’m on duty,’ he reminded her with a frown. ‘If I toddled off without a by your leave, I’d be for the high jump.’ He patted her cheek. ‘And you don’t want your neighbours gossiping, do you?’ He made a cautionary noise, rolling his eyes. ‘It wouldn’t do for the two of us to be looking cosy, having a rare old time, while poor Bill’s at death’s door.’

‘We’ve been together four years, ducks.’ June snorted a laugh. ‘The neighbours did their gossiping early on. My husband’s been knocking on the pearly gates for years, and I reckon everybody knows it’s about time he was let in.’

‘People have gossiped about us?’ Norman sounded surprised.

‘’Course they have,’ she said airily.

‘Aren’t you worried about that?’ Norman was wondering if he was. He’d trusted they’d been discreet enough for it to seem they were good friends through his late wife.

‘I’m not worried,’ she flatly replied. ‘I’ve done my duty and treated Bill better than he deserved, considering the dog’s life he led me. He’s never been liked. He used to cause trouble, picking fights; he still would if he was able to.’ June pinned on her hat. ‘I’ve got a day of it tomorrow with my Ginny coming over with her lot. The grandkids will be running around, driving me potty. I’m taking it easy tonight and having a drink. Are you coming?’ she challenged. ‘If not, I’ll go on my own.’

‘Oh, I don’t know . . .’ Norman sighed. ‘It’s irregular, you see . . .’

‘Nobody’ll come here, anyway. Not on Christmas Eve.’ She scoffed. ‘Who the bloody hell would want to?’

‘That’s just it, love,’ he said dryly. ‘Nobody wants to come here at any time of the year, but the poor wretches do.’ He stood up and clasped her hands. ‘How about we entertain ourselves another way?’ He jerked his head towards the box room that housed his bunk bed.

‘I’ll tell you what: we’ll have a little drink and a sing-song in the Bow Bells then I’ll let you unwrap your Christmas present tonight, if we’re both still in the mood.’ She jiggled her bosom at him and followed that up with a kiss on the lips.

Norman had felt a pleasant stirring as she’d shimmied and teased him with her tongue. ‘All right – just the one drink, mind. Then straight back here in case I’m missed by the boss.’

While she waited impatiently by the street door for him, hands on hips, Norman took off his slippers and pulled on his boots. Then he found his hat and coat. Once he was dressed for outdoors he felt more amenable to a jaunt. In the six years he’d been a workhouse porter nobody had ever knocked him up for admission on Christmas Eve. June was right. Even the destitute would try and hang it out until after the holiday before entering Whitechapel workhouse. And who could blame them? There was no Christmas cheer to be had in this place.

Norman loaded a few more logs onto the fire to keep it alight for a warm welcome home. Then he unlocked the door, a livening blast of wintry air greeting him. He quashed his misgivings. It was against the rules to go out. But he was sure he wouldn’t be missed if he deserted his post for half an hour.

The woman stomped to and fro, muttering to herself in irritation. She returned to the building and rang the bell again then banged on the door with a gloved fist. Still there was no sight or sound of life from within.

A fine soft sleet had started to fall, icing the pavements and her large black hat. The two children with her were silent. The elder of them was perching on the step of the lodge, with an adult’s long scarf wound around her neck and up over her fair hair, muffling her against the chill. The baby boy was in a wicker basket, his tiny body covered by an old cardigan used as a makeshift blanket.

‘Ain’t nobody opening up for yer?’ A fellow called out. He was stumbling on and off the pavement as he approached, swigging from a brown bottle.

The woman turned her back on him and squatted down by the children. From a distance it might seem she was lovingly protecting her offspring from the elements with her bulky figure. But she wasn’t their mother at all. She was a baby farmer who’d taken charge of these unfortunates, promising their mothers she would provide foster care. All Mrs Jolley loved was the money those desperate women handed over for their children’s keep. She pocketed it with no intention of earning the trust put in her. Over the past year she’d taken in half a dozen infants. All had been disposed of apart from these two. They too had now become a nuisance, and she wanted rid of them.

The tramp wasn’t discouraged by being ignored; he meandered over to stand swaying beside the little group. ‘Have yer rung the bell?’ Without waiting for a reply, he yanked on it himself. ‘Need to give it a good ol’ tug, missus.’

‘Clear off. We’re just having a rest and will be on our way shortly.’ The woman kept her hat brim low, shielding her middle-aged features. Not that she thought he would remember her; he was so inebriated he probably wouldn’t recognise his own face in a mirror. But she detested interference and didn’t want him drawing attention to her. Not that many people were about. They were at home, dressing turkeys or Christmas trees. Or they were in warm taverns, getting merry. She wanted to be elsewhere too and wasn’t hanging around for much longer. By the time the hostelries turned out she would be on the way to catch her train out of the capital to the suburbs.

‘Porter’s always in there,’ he insisted, unwilling to give up on being obliging. ‘Ol’ geezer must be goin’ deaf.’ Propping one hand on the door to steady himself, the other gripped the base of the empty beer bottle, employing it as a battering ram.

The thud, thud, thud was driving her crazy. She sprang up, shoving her mannish features close to his bristly face. ‘I said clear off. I don’t need your help, you drunken fool.’

He looked affronted and threw the empty bottle into the gutter where it smashed. He wended on his unsteady way, muttering about ungrateful cows. At the corner he stopped, still feeling resentful, and peered back the way he’d come.

His hammering on the door had been fit to wake the dead. It hadn’t brought the porter running. Nobody was home. But he would be back on duty at some time this evening, she was sure. She couldn’t hang about waiting for him. She was impatient to start afresh without encumbrances in a new neighbourhood.

She looked at the shivering girl, sitting huddled into her shawl with her scarfed head almost touching her knees. It was fitting that Charlotte Finch should return here. Her mother had been an impoverished widow who’d died in the workhouse infirmary, giving birth to her. The baby in the basket had been a factory girl’s bastard, offloaded at her parents’ command before the neighbours wised up to their daughter’s disgrace.

Mrs Jolley had no intention of introducing herself to the porter or giving any explanation for why she was abandoning the children. If she spotted a light go on inside, or heard the locks being drawn, she would hurry away. She crouched down by her foster daughter, shaking her shoulder to rouse her. ‘You must stay here with little Peter and somebody will come and let you in, and take care of you. Do you understand, Charlotte?’

The girl gave a nod, barely raising her head.

The baby peddler gave a final clatter on the bell, aware she was doing so in vain. Without a backward glance she set off briskly for the station, praising herself for having taken pity on those two and left them alive for somebody to find. It was more than she’d done for any of the others.

The little girl raised her head, blinking against the ice blurring her vision. Through the sparkles she could see somebody coming. It was the same man as before. He was wobbling as he walked and stopping now and then to find his balance. Mrs Jolley hadn’t wanted him to help with banging on the door. Charlotte would be thankful if he helped her. She was cold and hungry and her throat was very sore. She got up and used her small fist on the wooden panels, copying what she’d seen Mrs Jolley do. She hoped the man would hurry up and pull on the bell that she couldn’t reach. She put her ear to the door as Mrs Jolley had, listening for a noise from within. She couldn’t hear anything other than the hiss of the sleet and a sound of singing, somewhere in the distance.

‘You all right, nipper?’ The tramp was picking a careful path closer to her on the ice. He was too drunk to remember he’d thrown down his bottle. A piece of smashed glass pierced through the newspaper stuffed into the hole in the sole of his boot. With a yowl he hopped, flailed his arms, and toppled over onto his back.

Charlotte stopped what she was doing and hurried over to him. She bent down, yanking on his arm, then patting his face because his eyes were closed. When he blinked them open she skittered back. He didn’t smell nice or feel nice. His cheek had bristles that scratched her skin and she felt a bit afraid of him.

Jake Pickard continued gazing at the beautiful little child with big staring eyes and wisps of fair hair stuck to her damp forehead. She’d tried to help him up and had touched him with her soft-as-snow cold hands. He started to sniff and to cry in a long low whine.

Charlotte sped back to the step. She didn’t know what she’d done wrong. She’d only tried to help him. But she was always doing something bad even when she tried to be good. She peeked at Peter in the basket then tucked the old cardigan around him. She was about to sit down but the baby whimpered, taking her attention. Then she heard the singing growing louder, and somebody laughing. The wonderful sound was a lure. She set off at a trot in the direction of that happy person to ask them to help.

‘Oh, would you look at that! It’s a Christmas angel come down from heaven.’ June Gladwell removed her hand from Norman Drake’s shoulder where it had been tapping in time to the music being pounded out on the piano. He hadn’t heard her speak to him, nor did he notice when she stepped away to sashay towards the little girl standing just inside the doorway.

‘Are you looking for your mum, sweet’eart?’ The noise of the rowdy rendition of ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing’ was drowning out her voice but she continued grinning tipsily at the flaxen-haired child who had a length of tatty scarf drooping from her head and bundled against her chest.

June crouched down so their faces were level and she could gaze into a pair of deep blue eyes set in a white face. ‘My, you’re a cherub all right, and pretty as a picture.’ A smattering of ice crystals glittered on the girl’s fair hair where the scarf had slipped, and failed to protect her from the snow. June swept the cold spangles away with her knuckles then reached for her hands. She’d barely touched those small chilled fingers when they were jerked free and the child darted outside into the corridor, beckoning June to follow.

Unbalanced, June wobbled on her heels, whirling her arms, then tipped backwards onto her posterior. She gave a shriek that drew Norman’s attention, cutting short his carolling. He couldn’t help but chortle at the sight of her, though she was displaying her bloomers in a most unladylike manner. He put down his tankard and came to help her up.

The less inebriated patrons tutted; those coarsened by Christmas spirit hooted with laughter, encouraging her to show a bit more leg.

‘Ooh . . . me bleedin’ arse.’ June’s alley-cat roots broke through whenever she was under the influence. She gave herself a rub as she was hauled upright, and pushed her hat out of her eyes.

Norman had been having a rare old time, but he was on the way to being sozzled and June had had plenty to be making a spectacle of herself. ‘Time we headed back,’ he said, pulling out his pocket watch. He muttered a self-reprimand; he’d been gone from his post for well over an hour.

‘Ain’t going back till I’ve found the kid,’ June slurred stubbornly.

Norman put an arm around her and managed to propel her into the corridor, hoping that the cooler air might sober her up. He’d have to walk her home right to her door, the state she was in. He rarely did that. Daft as it seemed, considering he knew her husband was a bed-bound invalid, Norman imagined the brute might jump out and bash him. He’d known Bill Gladwell in his heyday when the man had been capable of causing a riot. June wasn’t exaggerating the rotten life she’d endured as his wife.

June wriggled free to attend to her hat with the fastidiousness peculiar to inebriation. ‘I know I wasn’t dreaming, Norm. I saw a pretty little girl and spoke to her.’ She traipsed along the corridor, leaning sideways to see past the kink in it. ‘Now where’s she gone?’

‘You’ll be seeing stars in a minute.’ Norman steadied her as she almost tripped over.

‘There she is!’ June waved. ‘See! Told you!’ She pointed triumphantly at the child, who was shivering and holding the scarf over her lower face as she peered round a corner.

‘She’s probably just waiting for her folks.’ Norman tried to urge June towards the exit. It wasn’t an unusual sight: kids loitering in pub corridors, or sitting outside on the step while waiting for their parents to finish drinking themselves silly in the warm.

The girl moved the muffling wool away from her face, revealing delicate features, framed by pale blonde hair. Now he had a better view of her, he recognised that pallid, heavy-eyed look. Sickness in the family was often the trigger for people entering the workhouse and ending their days in the infirmary. He moved closer and bent down to speak to her. In the wavering gaslight, he could detect blotches of feverish colour on her cheeks and blue hollows beneath her red-rimmed eyes. ‘Are you waiting for somebody in there?’ He pointed to the rowdy room. ‘Mother’s in there, is she?’

Charlotte shook her head. ‘Mother’s gone.’

Norman had inclined closer to catch her whispered words. ‘She’s gone in there for a drink, has she?’ He indicated the saloon bar again. ‘Shall I fetch her for you?’

‘Gone to the train. Peter’s crying. Come and see.’ She tugged on Norman’s sleeve. ‘I banged on the door but nobody’s there. Come and see.’ She muffled her neck again, wincing, as though speaking was painful.

‘You banged on a door, dearie?’ June butted in. Curiosity was sobering her up more efficiently than the draught in the corridor.

‘Is Peter your brother? Is he waiting outside?’ Norman held the back of a hand to the child’s clammy brow. She had a temperature. Perhaps she was delirious to say her mother was catching the train. In his opinion it would be kinder if parents left poorly kids at home, than drag them out to sit on a freezing pub step. All good intentions of ‘only being gone a minute’ disappeared after the first drink slid down. As he well knew; he’d intended having just the one. ‘I don’t think you’re well, little one.’ Norman sounded concerned. She looked underweight but that wasn’t unusual for East End alley scamps. ‘Is your throat sore?’ He’d noticed her wince on swallowing.

She nodded and automatically opened her mouth for him to look at what hurt her. Charlotte had got used to doing this when her foster mother asked to examine her throat. Mrs Jolley would groan after looking at it and seem annoyed with her for being ill. But this man didn’t mutter and tut, so she grasped his hand, trying to pull him towards the exit. It was warm and dry in here but she couldn’t stay. She had to go back and look after the baby.

Norman had bent down on creaking joints to take a look in her mouth and had got a whiff of her diseased breath. His expression was grim as he straightened up. He’d spent time in the workhouse infirmary as an orderly and knew about diphtheria and the havoc it caused, raging through poor communities.

A blast of icy air reached them as some revellers came in. The little girl took her chance. Before the door swung shut she darted into the street, trotting back the way she’d come. Norman rushed out after her, urgently beckoning June into the sleety night. She obeyed without a word, having also sensed an impending calamity.

The streetlamps were illuminating relentlessly descending snowflakes. Norman proceeded as fast as he could, conscious the pavements were now perilous. June clung to his arm, moaning at him to slow down as she skidded on patches of white underfoot. He had a mounting, horrible suspicion that he knew where the child was heading. As they drew closer to the lodge he squinted into the blinding atmosphere, making out a fellow by the building with an arm raised, banging on the door. Norman’s heart sank. His absence had been noted. The little girl leading the way was tiring and the couple soon caught her up. Norman firmly took her hand, helping her along those final yards.

‘Do you know these children?’ Norman puffed out to the local tramp.

‘Me? No . . . I . . . don’t,’ Jake Pickard barked indignantly. He’d dragged himself to his feet after his fall, but not in time to stop the little girl running off. The condition he was in, he knew he’d no hope of catching her if he gave chase. As he’d lain supine, snow had melted on his face, sobering him up. ‘The mother went off up there.’ He jerked his head. ‘Bold as brass, the cow. Left her kids behind in the snow.’ He spat into the gutter. ‘Shame of it.’

Norman quickly found his keys and opened up, bundling June and the child over the threshold. He picked up the wicker basket then went inside, slamming the door on the tramp, who was making a crafty attempt to follow them.

‘Settle the girl close to the fire to warm up,’ Norman ordered June. He put the basket down on the armchair and with stiff, unsteady fingers removed the wool cover, shaking the slush onto the floor. Norman stifled a groan. The little girl had said Peter was crying but this poor mite would never cry again. He looked about six months old and his sunken face was quite still and whiter than the grimy sheet he lay upon. Norman felt for a heartbeat beneath a bony ribcage but knew he wouldn’t detect one. He hung his head in shame, swaying it from side to side. ‘I should have been here.’ He sent a tortured glance June’s way. She appeared to be in a daze, gripping the mantelshelf for support. ‘This boy might still be breathing if he’d been brought indoors sooner.’ Norman covered his quivering lips with his fingers.

‘The wicked bitch that dumped them outside is to blame.’ June rallied to splutter a defence. She was also at fault, badgering Norman to go out when on duty. She gingerly approached to look at the tot. ‘He’s just skin and bone. The poor thing was too sickly to survive; his mother must’ve known it.’ She spat a tsk of disgust through her teeth. ‘Fancy that! Scarpering and leaving innocent little ones to fend for themselves on a night like this. Woman needs horsewhipping.’

Norman felt equally outraged by such odious behaviour. Destitute parents often brought sick children here for admittance to the infirmary, unable to afford a doctor’s fee. He’d never before found any abandoned on the doorstep, although he’d heard of it happening in days of yore. The woman’s heartless behaviour didn’t ease his conscience over his own dereliction of duty. He deserved a taste of that horsewhip himself.

‘You’re not to blame for this, Norman.’ June gave his shoulder an encouraging squeeze. ‘You’re a good man. One of the best. And nobody’ll know you weren’t about when the kiddies were brought here.’ She glanced at the child, huddled by the fireside. ‘Was only us two talked to the girl. And that old tramp won’t be believed, whatever tales he might tell. Pickard’s always hanging about, gabbling on about this and that. Nobody listens to anything he says.’

Norman knew that was true. Jake Pickard was a regular sorry sight, mooching up and down, and drunk whenever he could beg, steal or borrow the funds to buy booze. Norman had seen tykes chucking missiles and jeering at him. Yet a vagrant had been the first to take notice of two foundlings, then make an effort to protect them.

‘I know what I did, June.’ Norman stared at the girl resting her cheek on her drawn-up knees and holding her hands to the embers in the grate. ‘What a brave little thing she is; bless her heart for trying to get her brother help.’ He sighed. ‘I don’t know how she did it when she’s as ill as she is. I’ve let her down as well as the baby.’ He closed his eyes, thinking things through. ‘I imagine no father will come to claim them. Perhaps he’s away fighting . . . or could be he’s perished in the war, and the mother can no longer cope. I reckon the surviving child is now no better than an orphan.’

‘Don’t care if her mother is a war widow, what she did is pure evil,’ declared June. ‘The coppers should be after her. She needs locking up.’ The enormity of the tragedy had started June snivelling.

‘Coppers can’t help these two children,’ Norman said sharply. He didn’t want the police involved. The workhouse master was a stickler for keeping his business running smoothly to ensure the Board of Guardians were held at a safe distance. Any irregularities prompted an investigation and interference into the management of the place by the Whitechapel Union. Were Mr Stone ever to find out what had gone on tonight, Norman knew he’d be out on his ear. He wouldn’t just lose his job but his accommodation, and at approaching sixty-three years of age, he was too long in the tooth to start seeking new work and lodgings. ‘You can’t mention this to anybody, June. I’ll deal with it and put things right. First, the girl must quickly see a doctor, or she’ll end up going the same way as her brother.’ Norman bucked himself up; much had to be done and wallowing in regrets would waste time. He took June firmly by the elbow, steering her towards the door. ‘You should go home now. I have to clear this mess up and concoct a tale to tell the master.’

June didn’t seem as though she wanted to leave yet. She slipped her arm free, and made to uncover the baby again to study him for signs of life. But she tottered back at Norman’s next words.

‘I think the girl has diphtheria. Perhaps the boy had it too and it weakened him and that’s why he died. It’s a nasty infection, so don’t get too close.’

‘Gawdawmighty!’ June croaked. ‘Diphtheria! I’ve got me grandkids over tomorrow for Christmas. They can’t catch a dose of that.’ She shoved her hands deep into her pockets.

‘Go home, June.’ Norman led her to the door, opening it this time and making it clear she had to leave. She turned as though to wish him a merry Christmas, but seemed to think better of it. With a defeated shrug she hurried off into the quietly falling snow with barely a farewell.

‘Can you tell me your name?’ Norman asked the child while loading more logs onto the fire, stirring the embers with a poker until flames leapt up.

‘Charlotte Finch.’ The little girl didn’t raise her cheek from its resting place on her knees.

‘Well, Charlotte, you’re not very well, are you, dear? You’ll soon feel better once the doctor’s looking after you.’ Norman went next door into his bedroom and tugged a blanket off the bunk. He returned to the sitting room to carefully cocoon the girl with it. ‘Now I’ll make you a nice warm drink of milk. Then I have to go out. But I’ll be back and bring the doctor with me.’

‘Thank you,’ she murmured.

Norman felt a tenderness wash over him at her politeness and stroked her damp hair. ‘How old are you, dear?’

‘Five,’ she answered in a rasp.

‘No more talking for now.’ Norman had noticed her screwing up her face in pain. He heated the milk in a pan in the kitchenette then put the cup down on the hearth beside her.

He carefully covered the tiny corpse with the woollen rag and while patting it down felt something in one of the cardigan’s pockets. He drew out an old envelope. If the girl’s name was Finch the garment hadn’t belonged to her mother, he mused to himself, having read the scrawled name of Mrs Jolley and an address in Poplar. He thrust some fingers inside but whatever communication it had contained had been removed. He put the empty envelope into a drawer for proper perusal later, then picked up the basket. He would have to take Peter to the infirmary and report a dead child had been abandoned on the gatehouse step. The

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...