- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

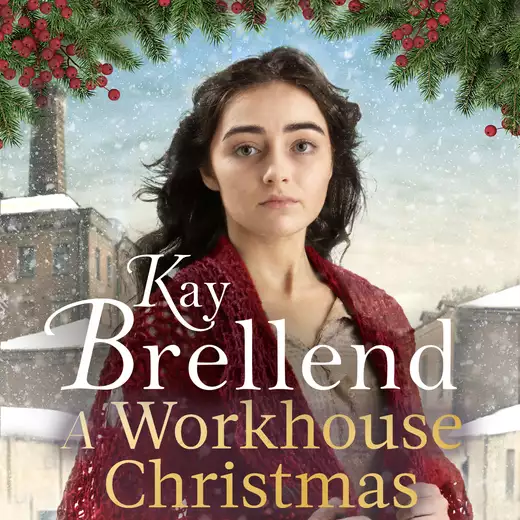

Discover the Workhouse to War trilogy by Kay Brellend: a new saga series set in the Whitechapel Union workhouse in East London, between 1904 and 1916. . .

Christmas Eve, 1909. Eleven-year-old Lily Larkin is left to fend for herself in an East London workhouse after her dying mother is taken to an infirmary: her future looks bleak. Once she is separated from her twin brother, Davy, her childhood hopes seem to shatter. But Lily's fierce spirit - along with her beloved new friends - help her to endure the miserable drudgery of life at South Grove Workhouse and its cruel supervisor, Miss Fox.

When a handsome, smartly-dressed gentleman shows up at the workhouse, claiming to be her cousin and with an offer of employment, Lily seizes her chance to escape. But her new job is far from perfect, and her reunion with her brother isn't what she thought it would be. Still, she relishes her freedom from the workhouse, and, finding herself on the cusp of womanhood, is determined to embrace her new life - until a shocking secret from her past is uncovered. As everything she'd ever believed about herself is thrown into confusion, will Lily ever be able to rise above her past?

Praise for Kay Brellend

'Vividly rendered' Historical Novel Society

'A fantastic cast of characters' Goodreads

'Thoroughly absorbing' Goodreads

Release date: August 27, 2020

Publisher: Hachette Audio UK

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Workhouse Christmas

Kay Brellend

‘Disobedient wretch! Show off in the street, would you? I’ll have you punished by the master, you brazen little madam. Do as I say and move on.’

Lily Larkin received another hefty slap on the shoulder that sent her stumbling forward. She steadied herself from the officer’s second blow. She’d barely felt the woman’s first, neither had she heard an initial barked command to get going that had accompanied it. Catching her breath, Lily hurried to catch up with her fellow pupils some yards in front. But her gaze continued to dart to and fro, seeking the wiry figure who had shocked her to a standstill and brought the girl behind crashing into her with a yelp. Nora Clarke had fallen over and Lily could hear her whimpering as the officer dragged her to her feet.

‘What’s up, Lil?’

The hissed question came from a fair-haired girl, wearing an identical shapeless dress, pinafore and ill-fitting boots to Lily’s. The two girls were marching side by side in a troop of students who’d turned out of the local schoolyard to head back to South Grove workhouse in Whitechapel.

‘Nothing’s up … just thought I saw a face I knew. But I was wrong.’ Lily told Margie Blake a lie because the truth was too astonishing and too precious to share even with her best friend. She had seen somebody she knew, and he had seen her.

In fact her twin brother might have been lying in wait on the Mile End Road to catch a glimpse of her. How she had longed for a glimpse of him over the years. She’d thought of him constantly, dreading that his dear features, so like her own, would grow unfamiliar as he turned from boy to youth. She’d stare at her reflection in the spotted mirror in the stone-cold bathhouse while pulling a comb through her washed hair, and imagine Davy with a moustache. But then she’d been told he’d never grow old, never need to shave. She’d been told her brother had perished. But he was alive and she had recognised him straight away. As he had recognised her. He had been gone from Whitechapel for several years but would remember the routine that she – and once he – had followed at the workhouse. The moment their eyes had collided, she’d frozen to the spot before instinctively rushing in his direction. But he’d slipped away into the throng on the pavement, and she had been hauled back into line by the dragon she hated.

Her twin hadn’t intended drawing anybody’s attention, even hers, and Lily regretted having nearly betrayed him. If he was a runaway he’d be punished if caught, then returned to the industrial school for the headmaster to decide his future.

Yet how could it be him if he was supposed to be dead?

The workhouse master and his wife had believed she’d bawl her eyes out and need comforting when they broke the news of the tragic accident that had deprived Lily of her last family member. Instead, she’d shouted at them, incoherent with distress, and had been called an insubordinate, ungrateful wretch in return. Who did she think she was speaking to? The mistress had roared at her, smacking her face and shaking her, making her teeth rattle. Lily had been in such profound shock on learning the ghastly news that she had smacked the woman’s face right back, earning herself more punishment. But Lily hadn’t felt the cane on her legs or the hunger in her belly when she was denied her usual meagre rations, sent to solitary confinement and given gruel.

She had sensed Davy beside her as she lay weeping, waiting for dawn to spill some light into the icy, dark punishment room, which was barely big enough to take a chair, table and the straw pallet on which she slept. She’d dreamt of him warming and comforting her during those interminable black hours. Her brother was no phantom. He was flesh and blood, and she’d just passed within yards of him. Her heart felt as though it might burst through her ribs, such was her joy at discovering the master and mistress had been wrong about Davy Larkin’s fate. She believed they’d been misinformed rather than had deliberately lied. She had some family left, after all; they might be orphans but they had each other. As children they’d been constant companions. Lily had always preferred being with Davy to mixing with school friends. He had been the one more likely to seek out chums to play with. Lily hadn’t begrudged him his freedom, knowing his friends had teased him when his sister acted as his shadow. Davy had also been the more mischievous twin, likely to receive a talking to from his father. Much as Lily had idolised her brother, she’d known Davy had deserved his reprimands too. Nevertheless, she would try to share the blame and the punishment with him, as they shared everything else. She’d do that now too, if need be. They were both of an age to be working. He might have been indentured to an employer and have illegally absconded. Whatever had gone on, she reckoned he had landed himself in some sort of trouble. And she must help him out of it, as she always did.

As she continued plodding along, Lily was aware of the officer watching her and at intervals growling at Nora to shut up snivelling because she’d scraped her knee. Lily felt guilty causing an accident; she’d say sorry later to Nora when they were in the dormitory. For now she must play her meek part and stop herself whooping in delight as exciting plans whizzed crazily in her head. She knew the officer would take a delight in trying to destroy her hopes and dreams of being reunited with Davy.

At her side, Margie was still frowning and giving her inquisitive looks; though bursting to tell her friend her wonderful news, Lily knew she mustn’t until she’d properly thought things through. Her breath was coming so fast that she might have been skipping along rather than trudging in time with the others. Outwardly she appeared as they did: downcast eyes, sullen expression. But beneath her unreadable excitement was anxiety. Her brother relied on her to be the sensible one, and already she was fretting he’d founder without her. She’d a thousand questions to ask about his escape from the fire at the Cuckoo School and his journey back to her.

After years of separation they were again close enough to breathe the same damp City air. The March drizzle had descended suddenly while she’d been doing arithmetic in the classroom. Though cold and shivery in her thin shawl, Lily was glad of the mist. It would give her brother cover if he needed it. An image of him on the last occasion they’d spoken flashed into her mind. She’d climbed the wall at their workhouse, determined to be the one to tell him their mother was dying. She could feel again his sharp bones digging into her palms, and see the tears glittering in his eyes as they’d embraced. She’d insisted he go to the industrial school when he’d spoken of remaining close to their mother until the end. She’d no longer have to bear the guilt of persuading him to go away, and that felt wonderful. Something bad had happened to him at the Cuckoo School, though, and she hoped he would forgive her for sending him to it. He’d returned to rescue her just as he’d promised. He’d have to bide his time before visiting the workhouse and applying to discharge her. The master would want proof that Davy Larkin had employment and the means to provide for his underage sister. The fact that the master believed her brother to be dead was another obstacle to her liberty. But Lily refused to let any pitfalls deject her; soon she and Davy would be building a little home together. And things would be all right again.

‘You’ll be sorry for making a spectacle of yourself, Larkin, I’ll make sure of it.’

Lily jumped as she was rudely jerked out of her thoughts. The threat had been issued close to her ear as she passed through the open gates of the workhouse. Lily raised her chin but kept quiet. Over the long years she’d been an inmate of South Grove, she’d learned to despise her enemies in private. She hadn’t liked Harriet Fox from the start, yet the woman seemed nastier than ever.

The line of girls began filing into the northern wing of the workhouse where female inmates were housed, away from the men on the southern side. Once within its walls, the group dispersed quickly and quietly through long, sour-smelling corridors. Some of the girls headed to the sewing room to join those mending and sorting rags. Anything at all that might be salvaged – buttons, hooks and braid – were cut off to be reused or sold. The money raised was put towards the cost of their keep, Lily imagined, as none of them ever saw a farthing for working their fingers to the bone. Other girls would be rostered to help their elders press and fold the vast amount of washing that had dried earlier in the week. Then, in an hour, it would be time to congregate in the dining hall, to sit silently at wooden trestle tables and be given a pint of milk porridge and five ounces of bread for supper. When first at the workhouse, Lily could barely stomach the food, even though she’d been starving hungry. The memory of her mother’s fare, even simple snacks like toast and dripping, was a distant one now, though, and she ate every scrap of the meagre rations put before her at mealtimes.

She made to follow Margie in the direction of the sewing room, but a pinching grip on her arm brought her up short.

‘You can stay right where you are, Larkin. You’re coming with me to the master’s office to explain yourself,’ Harriet Fox snorted. ‘Damned wretch, deliberately causing a rumpus and pretending to run off!’

‘I didn’t … it wasn’t deliberate!’ Lily protested, attempting to free her elbow. ‘I jumped out of line ’cos … I didn’t want to fall down meself. There were loose cobbles.’ It was a silly lie and had just tumbled out because her mind was still on Davy. Lily reckoned she’d have to continue with it now; she’d nothing better to offer, after all. ‘I didn’t want to rick me ankle in a pothole and miss school tomorrow. We’ve got a spelling test. Later I’ll apologise to Nora for what happened.’

‘What are you gawping at, Blake? Get to the sewing room and move that needle as fast as you can.’ Harriet cast a sneering look at the lame hand that Margie was concealing in the folds of her skirt. The girl was conscious of her disability, but Harriet took every opportunity to bring it to everybody’s attention.

Behind Miss Fox’s back, Lily pulled a face, letting Margie know that the spiteful cow wasn’t worth getting upset over. It seemed to brighten Margie up because she smiled at the flagged floor before hurrying off.

‘You’re a liar as well as a show-off, aren’t you, Larkin?’ Harriet turned back to Lily with a triumphant smirk. There’d been no pothole to jump over, and all it would take was a walk back down the Mile End Road to prove it. ‘You don’t need school spelling tests. You’re a dunce and no amount of extra learning will change that. Hard graft to knock the defiance out of you is what you need. And it’s long overdue.’ Harriet resentfully knew that the girl wasn’t a dunce. Lily Larkin was a gifted student and had been shown favouritism because of it. It was time to end that, in Harriet’s view.

The medical room was situated on the same corridor as the master’s office to which Lily was being rapidly propelled. Before Harriet could bang on her boss’s door, a young man in a white coat appeared in the corridor. Adam Reeve had been employed as South Grove’s medical officer for several years and had taken an interest in Lily’s education. Unlike his boss, he saw the point in encouraging bright children to learn and better themselves rather than regarding them all as fodder for labour in factories and kitchens.

‘What’s going on here, Miss Fox?’ Adam Reeve started towards them. Meeting Lily’s large blue eyes he gave her a sympathetic look.

‘Nothing that need concern you, sir,’ Harriet snapped back. He’d poked his nose in before and got the girl undeserved leniency.

‘I’ll be the judge of that, thank you. Is Lily Larkin in trouble?’

‘Oh, yes. She’s started a commotion in the street trying to run away, and caused another inmate to suffer an injury.’

‘I wasn’t running away, honest … I just—’

‘Hold your tongue!’ Harriet gave her captive’s arm a shake. She wasn’t sure why a man like Reeve had such a soft spot for the girl. But she knew why some of the other male staff showed an interest in Lily Larkin. She was developing fast. Unlike some of the other scrawny scraps of her age, Lily had blossomed into a pretty adolescent. Her mother had been a good-looking woman, despite the careworn lines etched into her face and the premature grey in her dark hair. Whenever Harriet thought of the late Maude Larkin, she resented Lily even more.

On hearing a barked command to enter, Harriet pushed Lily into the master’s office, then made to shut the door in Adam Reeve’s face. He thwarted her by placing a heavy hand on it and determinedly following her in.

‘Beg pardon, Mr Stone, but I’ve bad behaviour to report.’ Harriet thrust Lily forward in emphasis.

A baggy-faced fellow sprang up from behind his desk, clearly annoyed that a crowd had descended upon him just as he was enjoying tea and buns with his family. His wife remained seated in her chair. Harriet was pleased to see the matron with her husband, knowing she had an ally. Mrs Stone had no more liking for any Larkin than Harriet had herself. But there was another gentleman in the room, and he had recently been showing an interest in Lily as she grew more like her mother in looks. Harriet had been keeping a close eye on her boyfriend. She gave him a private smile but barely received a flicker of acknowledgement back. With a mutter for his parents, Ben Stone picked up his hat from the edge of the desk and quit the office.

‘Explain yourself, Larkin.’ Mrs Stone was wiping crumbs from her mouth with one hand and reaching for the punishment book on her husband’s desk with the other.

‘I’ve done nothing wrong, m’m. Nothing on purpose, anyway.’ Lily was still bubbling with emotion after seeing Davy and her reply sounded unintentionally flippant.

Bertha Stone pursed her lips. ‘Let’s have your version of what’s gone on, Miss Fox.’ She jerked her head at Harriet.

Harriet immediately made a meal of describing the disturbance, and the attention it had drawn from bystanders. With a flourish of her own skirt, she added that Nora Clarke’s clothing had got torn, knowing that the master would prick up his ears. Uniforms cost money, and Mr Stone liked to keep his accounts showing a good profit. Impressing the Board of Guardians with his efficiency kept them from poking their noses too far into his business. The master got furious if people in the neighbourhood witnessed inmates’ troublemaking. Any report of it reaching his masters would bring inspectors to his door.

‘The culprit can give the other girl her own skirt and patch the damaged one to wear herself.’ The master thumped a palm on the desk making the tea tray rattle. He flapped the same hand to shoo them out.

Harriet flushed angrily. She’d expected more punishment to be dispensed than a bit of sewing. Mrs Stone’s expression hardened too. She knew her husband was always shifty when Lily Larkin was brought face to face with him. Well, today he could squirm and suffer her presence. If Bertha had had her way, every one of the Larkins would have been gone from here by now.

‘Disorderly and refractory conduct cannot be tolerated or it will spread.’ She glared at her husband. ‘An example needs to be made of Larkin.’

Lily knew that speech meant she wasn’t going to get away with a telling off and some needlework. Adam Reeve usually stuck up for her when she got into trouble. She hoped he would now, though he’d hardly spoken so far. He was the kindest fellow she had ever known, and she included her late father in that judgement. In the early days Charlie Larkin had been a lovely man, but those memories were all but buried beneath what came after.

A reluctance to lose touch with Adam was one of the reasons Lily hadn’t fled from South Grove. Many times, when outside she’d been tempted to bolt into a crowd of normal people hurrying about their business. She was determined the workhouse’s pitiless regime would not break her spirit as it had that of others. The building was filled with souls who’d given up hope of ever leaving. And how they expressed their despair! The howl that erupted from their throats still had the power to chill Lily, though she must have heard it a thousand times. That eerie noise would echo in her memory until she died.

‘What caused you to step out of line, Lily?’ Adam asked mildly.

Lily gathered her thoughts and quietly repeated what she’d said earlier about the potholes. She couldn’t go back on it though she hated fibbing to him. She hadn’t fooled him; she could see the disappointment in his eyes.

‘She’s a liar as well as a troublemaker,’ Harriet crowed. ‘Every girl close by witnessed what she did. Larkin needs discipline and to be found employment. She’s wilful and spoilt from being allowed to idle at school for far too long.’

Harriet Fox claimed to be a trained nurse, yet had obviously received little education, and was jealous of those brighter than herself. Adam guessed she was probably the daughter of a handywoman who’d picked up the rudiments of nursing and midwifery from her mother. Workhouse employment was low paid and unpleasant. Masters asked applicants few questions and took who they could get in the way of staff. He was an example of such indifference himself. It was a mystery how Harriet Fox had risen to be a supervisor, though. It was common knowledge that she was Ben Stone’s lover, but that wasn’t the reason Harriet had been favoured by the master. Adam had overheard Mr and Mrs Stone talking about their dislike for the woman who considered herself to be their future daughter-in-law.

‘If Nora Clarke is injured, why isn’t she waiting outside my door for treatment?’ Adam found a pertinent question to ask.

‘Larkin’s punishment should be dealt with first,’ Harriet snapped at him for bringing that up. Nora just had a graze that needed a wash.

‘Enough of this.’ Mr Stone pushed himself to his feet as his two employees locked glares. The Larkin family had been a trial from the moment they had arrived. In the receiving ward they’d undergone a routine of being bathed and shorn and clothed in uniform, as were all new inmates. Thereafter families were separated. Men and women – even those who were married – boys and girls all taken in different directions.

Maude Larkin had been a force to be reckoned with, especially protective of her snivelling son. Her fierce daughter had been made of hardier stuff, and still was. William Stone knew she was watching him now with those deep blue eyes that seemed to dig into him. ‘A day’s reduced rations and solitary confinement for Larkin, and Reeve can look at the injured girl if he will.’

‘Reduced rations?’ Adam spat. ‘The diet here is barely adequate as it is. Children need sufficient nourishment. A lack leads to disease. If consumption takes hold again, it’ll go through the wards like wildfire.’ He strode forward, planting his fists on his hips.

‘She’s not a child any more.’ Bertha Stone continued writing her husband’s orders in the punishment book. ‘Larkin is not to be shown any further favouritism. I fear that our benevolence towards her has been abused. She will be disciplined then found employment.’ Bertha replaced the book on the desk, then hoisted her girth from her chair, mirroring the medical officer’s aggressive stance.

‘When are you fourteen, Larkin?’ The master avoided eye contact with the girl, thumping his pen repeatedly on the blotter.

Lily knew school for her was finished and that they were planning to send her to slave away in a scullery. Yesterday that would have felt like a death sentence. But not now. Davy was more important than school or Adam Reeve or her friend Margie. She felt guilty to be leaving Margie behind, but Davy was her flesh and blood … all she had left of her family. Though she’d not spoken to him in years, she ached with love for her twin brother and would always put him first. She didn’t care what job she got. Once outside, she intended to immediately abscond from it anyway, and find Davy. Together they would muddle along somehow. They had to, now they knew what the alternative was; they were never again entering a workhouse. ‘I’m fifteen, sir,’ Lily answered when reminded to do so by Harriet’s elbow in her ribs.

That admission made William Stone stare at her in shock. The girl didn’t look fifteen, but it was hard to tell sometimes whether the emaciated humanity that infested the building was aged twelve or twenty – not that he paid any of them much attention. ‘It is high time you were providing for yourself then. There are individuals far more deserving of shelter here than a healthy fifteen year old.’

‘Lily Larkin is exceptionally bright and that’s quite extraordinary considering who she is and where she is,’ Adam argued. ‘You know very well she helps out as a clerk and that has saved the Whitechapel Union the cost of a salary. Her continuing further education should be put before the Board for discussion. A shining example of a workhouse child achieving exemplary heights is just what is needed to promote South Grove and other such institutions. By the time she is sixteen she will be equipped with a handful of higher education certificates and ready for a clerical position in an office.’

Lily sent him a startled look. She didn’t want to further her education now, or be a shining example with a handful of certificates. It was too late for any of that. She wanted to be with Davy. That was all that was important, and she was sure if her mother could speak to her, she’d agree.

William Stone knew that the medical officer was right: Larkin was bright as a button and of use. He’d love to continue to have her free labour and also his own free time. The mountain of paperwork he was expected to do was an unwelcome burden, yet he was too mean to pay for an assistant. And he would adore to be lauded by the Board of Guardians for having produced gold from dross. The majority of children within these walls were fit for nothing but menial work, as were their feckless parents. But Reeve had brought to his attention before that this girl showed promise. If it had been anybody else, William would have overruled his wife and gone along with Adam Reeve’s thinking.

‘If Larkin’s got energy to spare to make mischief, she’s strong enough to be punished and to immediately be sent to work.’ Her husband’s hesitation prompted Bertha Stone to take matters into her own hands. ‘No matter her ability, employers will reject her because she’s too wilful. Larkin needs domestic work to keep her on her toes and tire her out.’

‘She’s too fine a student for that … ’

The more Reeve challenged him, the more determined the master was to impress on all present his authority. Besides, the girl’s presence was a constant thorn in his side. He’d sooner forgo any benefit to be had from keeping her and use this opportunity to rid himself of the last of the Larkins. ‘The matter is settled and there is nothing further to say.’ He flapped a hand. ‘Remove the girl for punishment, and steps will be taken to find her a suitable job.’

Harriet was above-average height for a woman and buxom with it. Her facial features were not unpleasant, but a look of triumph skewed them as she jutted her chin at Adam. Momentarily it seemed he had fight left in him, but he retreated from the office, shaking his head.

Harriet ushered Lily towards the door. ‘You know where to wait for me, Larkin. Go straight there.’ Harriet strode after Adam, catching up with him just as he was about to disappear into the medical room. ‘Don’t stick your nose into my business again, sir, or you’ll regret it.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ Adam turned to her, frowning. He was short for a man and their faces were level. ‘I’ve said nothing that wasn’t relevant or true about Lily Larkin. And I stand by every word of it.’

‘You just leave me to deal with her for the short time she remains here. If you don’t, I might turn my attention to dealing with you instead.’

‘Are you threatening me, Miss Fox?’

‘Wouldn’t you like to know.’ Harriet gave him a sly look. ‘Take the word of an inmate over mine, would you, and try to get me into trouble?’ Harriet smirked. ‘Dear me … I thought you’d been here long enough by now to know the rules, sir. Seems you don’t. So, I’ll oblige: don’t cross me or I’ll remember I know things about you that I shouldn’t.’

Harriet marched off, a gloating light in her eyes.

William Stone looked less cynical than his wife, but both had difficulty disguising their scepticism at what they had just heard. Having exchanged a hasty glance, the couple returned their attention to an uninvited visitor who had arrived a short while ago.

‘You say that Lily Larkin is your cousin, sir, yet there is no record of this girl having any living kin.’ William was seated behind his desk; he leant forward, planting his elbows on its edge. Over the steeple he’d made of his fingers, he squinted suspiciously at the fellow.

‘Well she is me cousin and I’ve come to get her. I’ve my own business and there’s work for her to do if she’s in agreement, that is. If she’s not …’ Gregory Wilding shrugged, curled his top lip and glanced about the master’s office. ‘She can stay right here if that’s what she chooses. I’ll find somebody who is keen to join the crew.’ He was standing, legs akimbo, one hand casually thrust in his pocket. The other was idly swaying a natty homburg by its brim.

William Stone ran an eye over the man’s get-up. Such tailoring – even when it was as tastelessly gaudy as this – cost a pretty penny. His resentment wasn’t confined to the fellow having found the audacity to dress in Savile Row when he spoke like a barrow boy. He didn’t like Wilding’s attitude either. Who did he think he was, swaggering in here and looking down his nose?

The master’s office was cosy, with its soft armchairs set upon a large square rug and landscape paintings on the wall, all lit by the dancing flames of a coal fire. But this fellow didn’t seem impressed by his environment. William had no intention of ejecting him though. He’d taken against Gregory Wilding straight away; nevertheless, the man was a godsend.

‘Have you more information about this family connection you claim to have with the Larkins?’ Bertha Stone piped up. ‘Inmates can’t be discharged willy-nilly, you know.’

‘Can see yer predicament, sir … ma’am.’ The fellow gave an emphatic nod. ‘Let me fill you in on some background then. My mum was Lily’s mum’s big sister and they didn’t get on. Never spoke for years, so us kids hardly knew one another. I don’t have a gripe with Lily though. Not seen her since she was toddling, but when I found out on the grapevine that she was stuck all alone in Whitechapel workhouse, me heart went out to the girl. I reckon I ought to step up and do my duty to family. She’s had more’n her fair share of knocks. Orphaned, then the poor kid lost her brother ’n’ all.’ Wilding shook his head, expelling air through his teeth. ‘The lad would’ve been better off taking his chances on the street than going to that school and ending up burned to a crisp.’

William Stone inserted two fingers between his tight collar and his florid throat. He didn’t like reminders of that episode; he regretted what had happened to the innocent boy. He was thankful, though, that the wretch who had accompanied David Larkin to Hanwell had left when he did, or he might have set a fire here rather than the Cuckoo School. Most of all he was sorry that the dratted incident hadn’t been kept out of the papers. It was too much that an East End wide boy knew about it and had just thrown it in his face.

‘Be surprised what’s picked up on the streets, sir.’ Greg had interpreted Stone’s brooding look. ‘Once gossip starts it don’t stop and gets hairier along the way. I’ve heard folk say they’d sooner strangle their kids than hand ’em over to the Whitechapel Union.’

‘Unfortunate accidents happen,’ William snapped while his wife fidgeted.

‘Indeed they do, but still makes me fret for me last remaining cousin, as you can imagine. Doesn’t seem right her still being here.’ Greg Wilding strolled to the window and stared out into a bleak April afternoon. ‘I need more workers and she’s deserving of a change of luck. No harm in helping kin who’ve done yer no wrong, is there?’

Lily had been standing just inside the door, ignored as though she wasn’t worthy to be a part of this discussion concerning her family and her future. But it had suited her very well to keep quiet and listen intently through the sound of blood pounding in her ears. Her lowered gaze was busy watching all of them … especially the handsome stranger.

Ten minutes ago, Harriet Fox had come looking for her and beckoned her away from the mangles in the steam-filled laundry room. Lily’s questions about why she’d been summoned by the master and mistress had been answered only by a scowl and a shove on the shoulder, sending her on her way to the office. F

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...